I scalped my first ticket in 1985.

It was the summer before my freshman year in college, Springsteen was on the last leg of his Born in the U.S.A. tour, and my best friend was interning at a financial services company. The night before tickets went on sale, we gathered up our sleeping bags and bivouacked on the suburban sidewalk of a now defunct department store, prepared to buy as many as the limit would allow. Our priority was to snag seats for ourselves, but if stockbrokers and bankers were inclined to overpay us for the rest, well, that would just be compensation for our time. The counter opened at 10:00, but the dozen tickets we bought at 10:09 were decent at best. Which is why every dollar we made reselling them went to a more accomplished scalper, who sold us a pair of floor seats that were still too far away.

It’s not much of a mystery why we came up short. Even before the Internet or cell phones, insiders and pros found ways to lock up all the killer seats: hiring homeless men to stand in line and college kids to work the phones, exploiting connections at the venue, romancing clerks from the department store with daiquiris at Bennigan’s. Clearly, there’s a lesson there: No good can come from buying or selling tickets when your motives aren’t pure. But have I learned anything? No way.

Not as a seller, despite eating hundreds of dollars’ worth of tickets over the past two decades—sometimes purchased with the best of intentions (extras for friends who couldn’t follow through), sometimes not so much (as a Dallas Stars season-ticket holder, I had no qualms about using the games I wasn’t planning to attend to pay for those I did, which worked great for a few years after they won the Stanley Cup—until it didn’t). Certainly not as a buyer, even after our too-good-to-be-true tickets for a big Ohio State football game in 1996 were in fact just that—stolen from two members of the class of ’39 who were already in their seats thanks to replacement tickets when my dad and I arrived (this might have been a more traumatic memory if the Columbus cops had treated us as suspects, but they didn’t even make us leave the stadium). And definitely not at my favorite place to wheel and deal: the men’s Final Four, which comes to San Antonio for the fifth time on April 5 and 7.

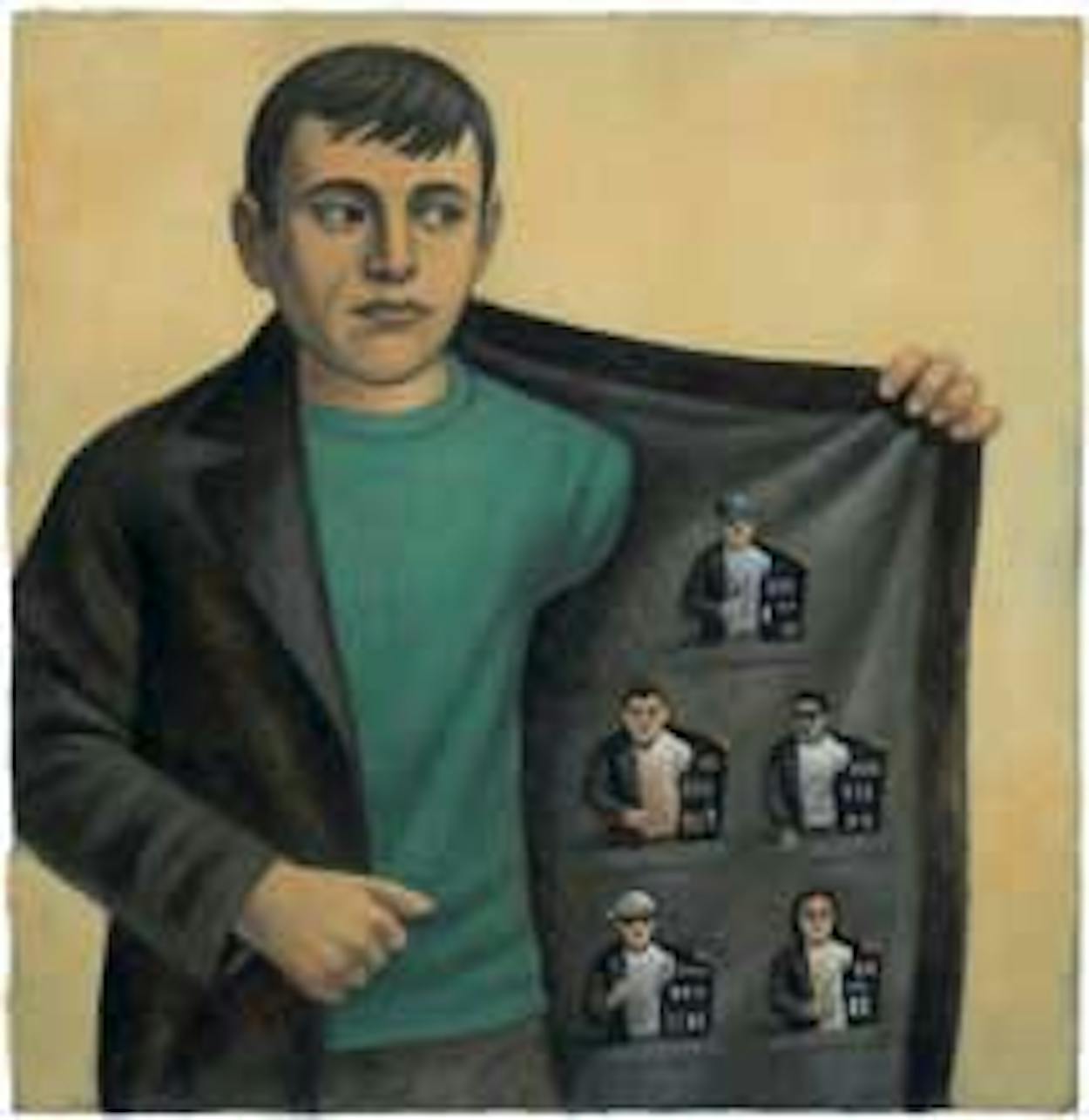

Unlike the Super Bowl, the face value of a ticket to the Final Four (between $140 and $220 for the three-game package) is not offensive to begin with. And unlike the World Series or NBA championship, there are neither season-ticket holders nor hundreds of thousands of home fans wanting in. Instead, there are 341 NCAA Division I institutions with assistant coaches, staff, and favored donors, plus a slew of national and local sponsors, with first dibs on seats. But who’s to say that all of them will use their tickets? There’s also the inevitable pool of seats that once belonged to fans whose teams did not get through the bracket. This makes a target-rich environment for guys wearing “I Need Tickets” signs around their necks (FYI: they really don’t need tickets) while looking out for cops and earning dirty looks from passers-by.

Needless to say, I’ve never understood the general public’s ire over scalpers. If I buy an old dinette set in a town like Big Spring for $10, then sell it for $50 in Austin, I’m an antiques dealer. If I buy fifty handmade blankets from a Quechua Indian in Ecuador, then sell them in the United States for five times what I paid, I’m an importer. But if I put my time and money into buying tickets on the Internet that people with more money and less time want to pay double for? For shame! Sports might be the only instance where Americans are massively pro-regulation and resolutely anticapitalist.

It’s perfectly understandable to loathe a system that makes going to the game a matter of being the person with the biggest wallet rather than the greatest passion. But isn’t that already so? The modern arena, with its luxury boxes and club seats, is like a 747 with more spots in first class than coach. “Seat options,” which merely give fans the opportunity to buy season tickets, are expected to add thousands or even tens of thousands of dollars to the bill of every customer at the new Dallas Cowboys stadium, in Arlington. Good tickets to college football games are inevitably tied to donations (even if they are 80 percent tax deductible). More recently, the teams themselves have entered what’s known as the “secondary market” via “exchange” programs (on their own sites or with a third party) or partnerships with online tickets kingpin StubHub. This allows the Dallas Mavericks, for example, to share in the profit when a guy like me sells a $33 upper-level ticket for $120.

With the Internet and team involvement, what used to be akin to picking up a hooker is now more like online dating. But that doesn’t mean it’s always better for the fans. Online tickets always go to the highest bidder, but on the street, patience, shoe leather, and negotiating prowess count for something (plus, your scalper may have paid only half price). And the fewer tickets that are sold through eBay or StubHub in advance, the cheaper they will be on game day. A free market is an open market, which sometimes means a soft market. After the semifinals at the Final Four, on Saturday, a certain number of fans will stream out of the Alamodome as sellers, bummed their team just lost and ready to go back to Kansas, Tennessee, or California without attending Monday night’s national championship (I hesitate to make predictions, but if the UT Longhorns play on Saturday and lose, change “a certain number” to “10,000 or 15,000”). You can surely score a ticket at a bargain price then—assuming the professional scalpers don’t get there first.