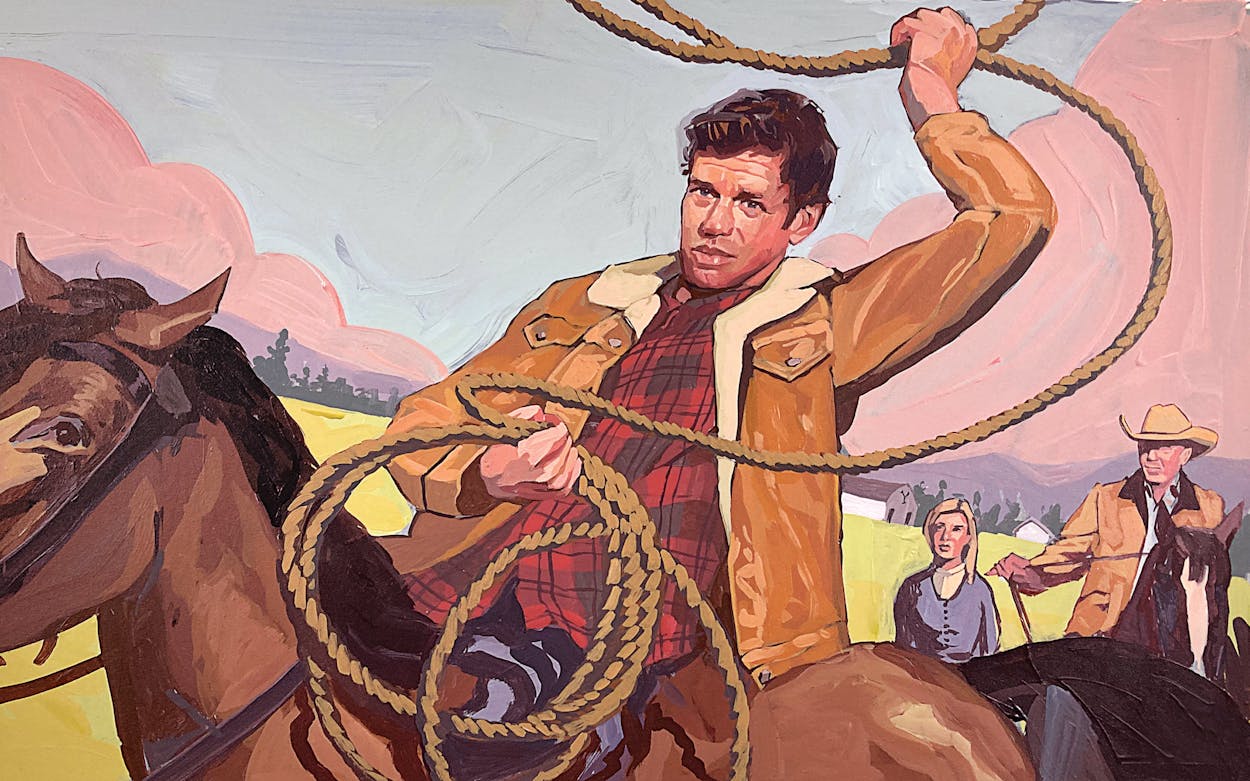

Taylor Sheridan’s work is full of cowboys. They don’t always wear hats and ride horses, but they live by a code of individualism and defiance. Brooding, trigger-happy CIA paramilitary officer Matt Graver (Josh Brolin) battles drug cartels on the El Paso–Juárez border in the 2015 film Sicario. West Texas brothers Toby and Tanner Howard (Chris Pine and Ben Foster) rob banks to save their family’s ranch in the 2016 heist thriller Hell or High Water, for which Sheridan earned an Oscar nomination for best original screenplay. Mike McLusky, a volatile, callous ex-con played by Jeremy Renner, calls the shots in a Michigan town dominated by the private prison industry in the Paramount+ show Mayor of Kingstown. Montana smoke jumper Hannah (Angelina Jolie) extinguishes flames while protecting a teenager from assassins in last year’s Those Who Wish Me Dead.

The 52-year-old Sheridan is a native of Cranfills Gap, an hour northwest of Waco, and his stories, which he creates at a head-spinning rate, are inspired by familiar Texas archetypes. His tales are ones of pride and vengeance, peopled by stubborn men and women who live by primal instincts and cold-blooded calculation.

His biggest hit, the most-watched show on television across cable, premium, and broadcast last fall and the fount of an ever-expanding creative universe, is Yellowstone, which he cocreated with producer John Linson. At its center is John Dutton (Kevin Costner), who rules the country’s largest ranch with an iron fist and will do anything to protect his land from the forces of modernity, be they hotel and casino developers or corporate raiders. (The man even resents cell service.) If that means committing murder, then so be it.

Yellowstone is bloody, and it’s soapy, but it has a Shakespearean streak to it. Dutton is a jeans-and-boots-wearing King Lear with three adult children: the intensely loyal, business-savvy, and alcoholic Beth (Kelly Reilly), the selfish and anguished Jamie (Wes Bentley), and the favorite son, a former Navy SEAL named Kayce (Luke Grimes). There’s also Rip (Cole Hauser), the strong and silent adopted ranch hand who is Beth’s amour.

Together they juggle multiple threats against Yellowstone Ranch as they wonder, along with viewers, who will inherit the keys to the kingdom (if the kingdom survives). This crown jewel of the Sheridan empire runs on momentum every bit as much as prime-time eighties potboilers Dallas and Dynasty. But the Ewings and the Carringtons have nothing on the Duttons in terms of salaciousness and ruthlessness.

Since it began airing in 2018, Yellowstone hasn’t really rung critics’ bells or set the Twitterati chattering—reflecting a familiar cultural divide. Just a couple of weeks before Yellowstone’s premiere, another show about loyalty, favoritism, and dysfunction within a wealthy family—HBO’s Succession—debuted. The New York–based show has received as much praise from critics as Yellowstone has quiet shrugs of indifference, or worse. Vanity Fair recently called the latter the “most-watched show everyone isn’t talking about.”

Indeed, Succession’s peak viewership, 1.7 million across all platforms for its season three finale in December, pales next to Yellowstone’s average viewership of 10.4 million on the Paramount Network for its fourth season, which concluded in January. Yellowstone may not have Succession’s metropolitan cachet, but it’s inspiring a cultural wave reminiscent of 1930s Hollywood westerns’ popularization of everything from dude ranches to blue jeans. Last year Wrangler released a Yellowstone-branded clothing collection. Rodeos, which feature prominently in the show, have experienced a surge in popularity, with increased attendance at events and star rodeo athletes appearing in cameos on the show.

A running joke among younger wags is that only their parents watch Yellowstone. Sheridan’s story unfolds in a red part of the country, and it doesn’t trade in the clever if often profane wit of Succession’s Roy family. But Yellowstone doesn’t fall along neat political and cultural lines. Yes, in addition to its cowboy aesthetics, there are elements that appeal to a conservative viewership. The Duttons never miss an opportunity to denigrate stand-ins for urban liberal culture, whether it’s vegans or pour-over coffee. In one memorable scene, Dutton disperses a gaggle of Chinese tourists by shooting his rifle in the air after one member of the group posits that it’s unjust for Dutton to own so much land. “This is America. We don’t share land here,” Dutton says, snarling. And the show’s central premise—that John Dutton, standing athwart history, is the last bastion of a way of life being besieged on all sides—goes to the emotional heart of today’s conservatism. Possessing land and demanding that everyone and everything inside the fence live by your personally defined ethos represents one conservative conception of freedom.

Yet for a show that early on was breezily labeled “conservative prestige TV,” it complicates its politics with progressive elements. It’s one of the few popular series to feature multiple fully realized Native American cast members, including San Antonio–born Gil Birmingham, who draws from his Comanche heritage to play Thomas Rainwater, chief of the Broken Rock Reservation and Dutton’s most respected adversary. He operates under the principle that Dutton’s land belonged to Native Americans first and should be given back to them— a stance for which Dutton has little response except to alternate between ignoring and politically outmaneuvering Rainwater. Yellowstone’s soundtrack includes music by such artists as Jason Isbell and cast member Ryan Bingham, neither of whom would ever be mistaken for reactionaries. But most of all, much of the show’s plot develops from the negative consequences of Dutton’s absolutist worldview. He’s willing to alienate family, damage his children, make enemies, and go to the extremes of villainy before reconsidering his precepts. The resulting blowbacks only threaten his grip on power and his land. Remember, King Lear is a tragedy.

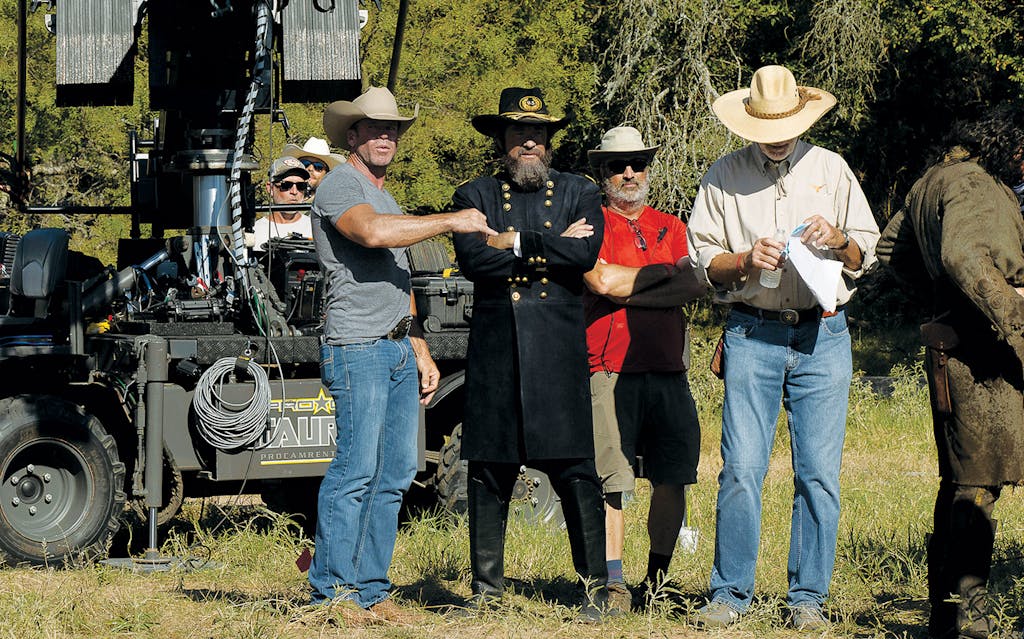

Yellowstone’s popularity and beguiling character arcs made it deserving of a prequel series, and it got one in 1883, which Sheridan wrote (he also somehow found the time to direct one episode and codirect another). The first season ended in February and performed well enough to earn a second season and a green light for yet another Yellowstone spin-off, 1932, a sequel to the prequel. Airing on Paramount+, 1883 tells the origin story of the Dutton family and features Tim McGraw as John Dutton’s ancestor James, Sam Elliott as tough guy/grieving widower Shea Brennan, and LaMonica Garrett as Thomas, an ex–Buffalo Soldier, a Pinkerton agent, and Brennan’s travel partner. The show tracks the group’s rough journey west from Fort Worth—depicted as an unruly town where brawls are just waiting to happen—and how the Duttons ultimately choose to settle in Montana, where they’re destined to carve out their ranch dominion.

1883 is the rare Texas story that was shot at least partly in Texas, with locations in Amarillo, Fort Worth, Granbury, Guthrie, and Sheridan’s thousand-acre Bosque Ranch, in Weatherford. (Filmmakers looking to capture the Lone Star flavor often decamp to New Mexico, where tax incentives are more alluring and state officials are less openly hostile to “Hollywood.”) The show is less guided by vengeance and not as pulpy as Yellowstone, which paints in broader strokes and delivers swifter satisfaction. Hired to guide a large party of ill-prepared European immigrants from Texas to Oregon, Brennan, still mourning the death of his family from smallpox, teams up with Thomas and James for the dangerous trek. They face rattlesnakes, a tornado, perilous river crossings, bandits, and other hazards across the untamed land.

Early on, they find themselves in Hell’s Half Acre, Fort Worth’s notorious red-light district, where pickpockets are shot in the back and strung up on the street. Dutton gets a bit of advice from the man in charge of storing his wagon and horses: “You don’t want your family here. You should go to Dallas.” It’s a line that’ll amuse anyone who takes sides in the eternal Dallas–Fort Worth rivalry.

1883 revels in a bit of Lone Star exceptionalism courtesy of the show’s seventeen-year-old narrator, Elsa Dutton (Isabel May, who bears more than a passing resemblance to Jennifer Lawrence). The daughter of James and his wife, Margaret (played by McGraw’s real-life spouse and fellow singer Faith Hill), Elsa is given to rhapsodic descriptions of the Texas plains. “Ah do not know what the word ‘Texas’ means,” she tells us. “To me, it means magic.” Or: “The whole of Texas spread out before me. It was the most magnificent thing ah’d ever seen.” These lines come off like made-for-TV Terrence Malick; they momentarily sap whatever grit and realism the show has accumulated. They’re more suited to the Texas Travel Alliance than a western.

Though these voice-overs position Elsa as the heart of the show, that’s less of a surprise than some might assume. Yes, Sheridan’s world is fueled by testosterone, but some of the strongest characters in Yellowstone and 1883 are women. Beth Dutton is the boldest gangster, the one you’d least like to cross on a show that often plays like a Rocky Mountain rendition of The Godfather. Elsa is the most independent thinker in 1883, a modern young woman who claims the right to love on her own terms (and gets her heart badly broken in the process).

Sheridan’s grown men aren’t afraid to cry either. When Brennan, haunted by memories of the Civil War, grieves the death of his wife and daughter, he wails with the pain of a wounded animal. As the series begins, he’s deciding between two options: head west or put a bullet in his head. This is some of Elliott’s best work, sensitively portraying a rugged but achingly vulnerable man. He’s a reminder that there are no cardboard characters in Sheridan’s universe. Sheridan’s tough guys feel the brunt of the world’s cruelty. And he doesn’t tell only the story of white pioneers: Thomas falls in love with a widowed Roma woman (Gratiela Brancusi).

1883 is elegiac in its depiction of the travelers’ suffering as they slowly make their way west. Its violence comes with a sadness that never really infiltrates Yellowstone, despite the losses suffered by the latter-day Dutton family. 1883 wants you to know that settling the West was hard, often soul-draining work. There are no bunkhouse shenanigans here and there’s very little respite, although Margaret manages to get drunk with a friendly merchant (Rita Wilson, whose husband, Tom Hanks, also has a cameo this season).

Still, much of the acting in 1883 is merely adequate. And sometimes the show comes off a bit slapdash: fans recently took to social media to observe that in a recent episode Elsa was wearing hair extensions. (The anachronism was unfortunately highlighted by the episode’s title: “Lightning Yellow Hair.”) Reviews of the show have been mixed, from positive comparisons to Lonesome Dove to scornful takedowns of the show’s hammy, old-fashioned tone. However, one suspects that Sheridan, gazing upon his own western empire, is too busy sharpening his spurs to care.

This article appeared in the April 2022 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Rope Operas.” An abbreviated version originally published online on January 5, 2022. Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Television