Five mornings a week at around seven o’clock, 66-year-old grandmother Isabel Lopez slips on boots and a floppy hat and disappears into the South Texas desert. She won’t say exactly where she is going, only that it is within a two-hour drive of her home in Oilton. Somewhere amid the spiny brush and rattlesnakes, she parks her truck and sets out on foot to the base of nearby hills or the shady patches beneath mesquite trees. Using a modified hoe, she spends the next several hours chopping hundreds of low-growing cacti, taking care to leave enough root intact for the plants to regenerate. She then stuffs the knobby blue-green buttons into burlap sacks. And though she is perfectly aware that the Controlled Substance Act of 1970 classifies her harvest as a Schedule 1 drug (along with marijuana, heroin, and LSD), she makes no effort to conceal her potent truckload when the time comes to head for home later in the afternoon. Lopez simply smiles at the border patrolman at the checkpoint outside of town. He smiles back and waves her through. At home she sets her cache out in the yard, in anticipation of visitors who will drive thousands of miles to buy her wares. Many of her customers will ingest their purchase right there on her land.

The cactus is peyote, Lophophora williamsii, and it contains the powerful hallucinogen mescaline. For better or for worse, peyote grows nowhere in the world except an arid region that runs through northern Mexico and up into Starr and Webb counties. For 200,000 members of the Native American Church, many of them Navajos, peyote is a “medicine” taken legally as part of their religious ceremonies. Lopez is one of nine Texans—six in Rio Grande City, on the border, and three in the area around Oilton, Mirando City, and Bruni, about forty miles east of Laredo—who are licensed by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency and the Texas Department of Public Safety to harvest and sell the plant to Indians. By the laws of nature and man, Texas is the only state with such an industry.

The Indians of Mexico may have taken peyote as early as 300 B.C., but Native Americans didn’t begin the practice until the 1870’s. As a legal maneuver, Indians incorporated the Native American Church in 1918, proclaiming peyote as an essential ingredient of their religious ceremonies. For the first seventy years of this century, buying peyote was easy. There were no federal laws against it, and the drug was obscure to all but the Indians who made pilgrimages to South Texas or bought it by mail. Quite simply, nobody cared.

In time, however, peyote caught the attention of non-Indians, thanks first to The Doors of Perception, Aldous Huxley’s account of his 1953 experiments with mescaline, and then to The Teachings of Don Juan, anthropology student Carlos Castaneda’s 1968 tale of apprenticeship to a peyote-eating medicine man. Soon hippies by the vanful were trespassing on South Texas ranches; the federal government reacted by making the plant illegal to all but Indians. Today only licensed distributors like Isabel Lopez, Salvador Johnson of Mirando City, and the Reyna family of Rio Grande City can deal the drug.

To get a state license, an applicant must submit letters of reference from a county judge or chief of police to the DPS in Austin. The DEA expects only a completed application form. The federal license runs $125, and the state charges $5; both permits are renewable yearly. The DPS also issues authorization cards to harvesters employed by distributors. A licensed dealer can sell to Native American Church “custodians” or to any card-carrying member of the church who has been designated by a custodian (members must be at least one quarter Indian). A distributor is encouraged to keep a fenced-in area for drying peyote buttons and must file quarterly sales reports with the DPS. DEA agents visit only about once every three years. The system is remarkably loose, which has a lot to do with the remoteness of the region where peyote grows. And as DPS captain B. C. Lyon observes, “Peyote doesn’t reproduce very quickly, so distributors are very protective when outsiders come in to pick it. They police themselves.”

Indeed, peyote is almost impossible to cultivate. Once a seed germinates, the plant takes five years to grow big enough for picking, and the root of a harvested peyote takes nearly that long to bloom again. Dealers worry constantly about running out of stock, so they keep their sources secret from outsiders and even from each other. They are also afraid that if Indians ever discovered the choice growing areas, they might try to bypass the dealers.

An even stronger deterrent to popular use and rapid depletion is the drug itself. Peyote tastes bitter, and those who eat it usually must weather a bout of violent vomiting before the heralded hallucinations begin. Even the Indians dub peyote a hard road and keep a “shovel man” on hand during ceremonies.

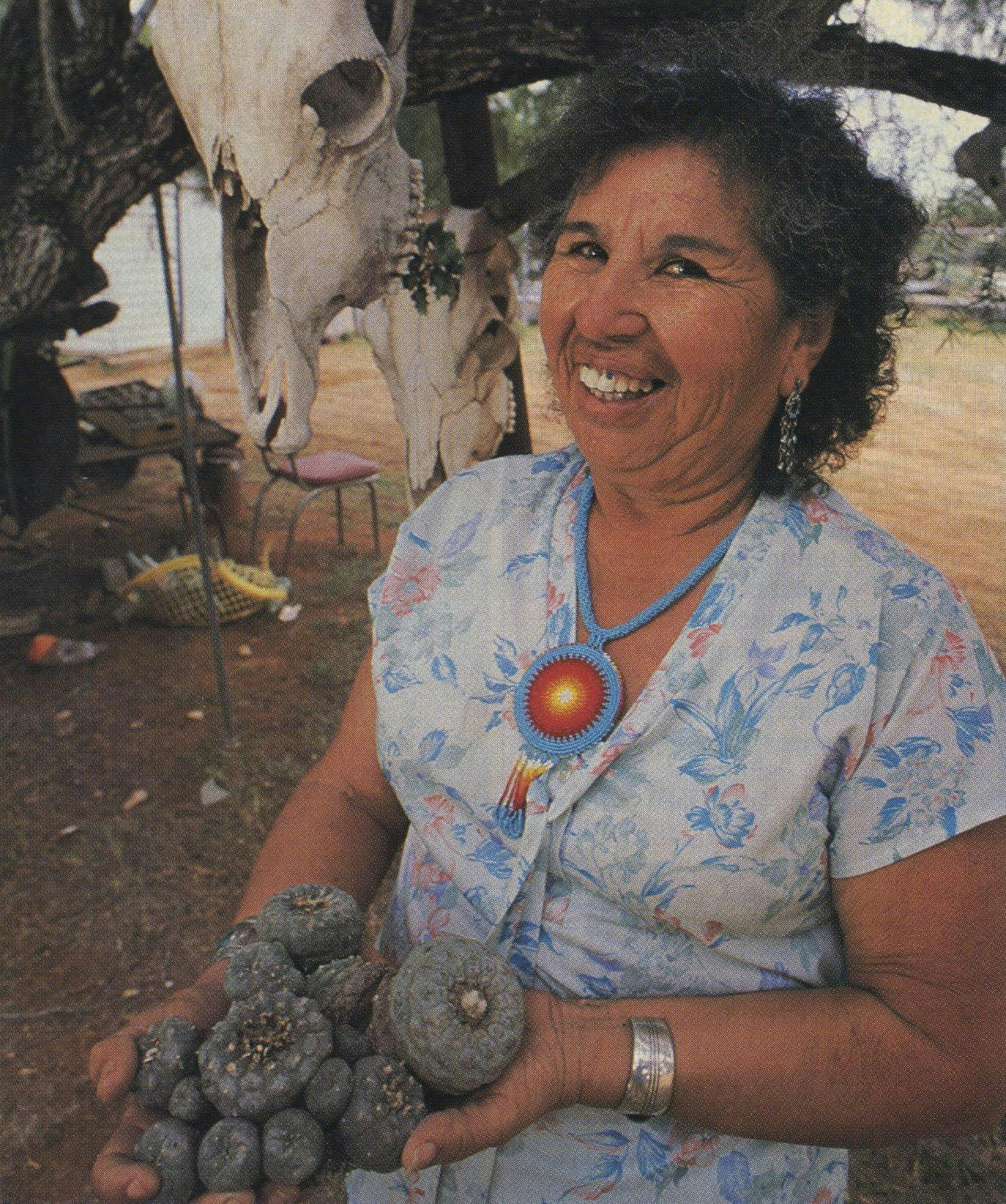

“This is all I know how to do,” says Lopez as she walks beside tables of peyote drying in her back yard, pressing each button down with her thumb. Lopez does her own picking and will keep fresh buttons for three days for customers who prefer to ingest them undried or wish to boil them for tea. After several days peyote buttons start to go bad if they are not dried in the sun. Drying takes at least two weeks and leaves the buttons as crisp as potato chips. In that form they remain potent indefinitely and are much lighter to mail. Lopez sells her fresh buttons for $80 a thousand; dried, they are $100 a thousand.

For her efforts Lopez grossed about $35,000 in 1986 and a little less last year. Besides gas money, her expenses include $2,500 to $6,000 a year for the lease of ranch land. A gregarious woman who talks fast and laughs easily, she says she can make enough money selling peyote to support her husband and a disabled son. She also says that by mixing ground-up peyote with petroleum jelly and rubbing the compound on her body, she has been able to arrest her diabetes.

Selling buttons at a slightly lower price in Mirando City a couple of miles away is shaggy-haired 41-year-old Salvador Johnson. He netted about $14,000 for six months’ work last year and supported his wife and four children while paying $3,000 for leases, plus wages for several pickers. He also became the first dealer ever to have his license suspended; one of his pickers was caught trespassing. Johnson is also one dealer who acknowledges having attended peyote ceremonies.

Although peyote is cheaper and easier to buy through the mail, many Indians prefer to purchase it in person. Usually they come in small groups, load up thousands of buttons, and drive home. But each year in February, two thousand to three thousand Native American Church members journey to Oilton for a special ceremony. Lopez and Amanda Cardenas, a former Mirando City distributor who is still a secretary in the church, keep long poles on their properties for the Indians’ tepees. Lopez also opens her kitchen to them and gives them use of a house next to her own.

Inside each tepee, a typical ceremony runs from sundown Saturday to after sunrise Sunday, during which time participants may eat anywhere from eight to forty buttons apiece. Indians sit in a circle with the chief facing east. All through the night, sounds of praying, chanting, drumming, and story-telling escape into the Texas sky.

Oilton, which hasn’t seen oil for so long that it might as well readopt its old name, “Torrecillos,” takes the Indians in stride. Not only is peyote a source of income for several of Oilton’s citizens, but it also provides trickle-down benefits for the community at large. Justice of the peace Ernesto J. Salinas sees the yearly ceremony as just another convention. “When the Indians come,” he says, “we think of it in terms of the Texaco station is going to sell an extra thousand gallons of gas.”

When peyote is in short supply in Webb County, Indians head 75 miles south to Rio Grande City, though they stick around only long enough to make their purchases. The largest dealer near Rio Grande City is probably the Reyna family. Roque Reyna, 79, started the business; his wife, Vicenta, holds the license. Sons Armando, Amando, and Arnoldo run the show. In their yard, which is presided over by a pit bull that Arnoldo says is part of the security system, the Reynas have planted a small covered peyote garden with a brightly painted plaster Indian in one corner to watch over the plants. While waiting for orders to be filled, customers often chant and pray, tossing turquoise and coins into the garden.

When Roque launched the business in 1976, family members drummed up customers by patrolling the streets of Rio Grande City and stopping any car bearing Arizona or New Mexico license plates. Today the Reynas sell 500,000 to 600,000 buttons a year, one third by mail. None of the family members likes to pick, so they pay workers $45 per thousand buttons, reselling at $75 per thousand fresh and $90 per thousand dried. The Reynas gross about $50,000 annually, which supplements the income from Roque’s small cattle ranch.

Like their counterparts near Oilton, the Reynas know the other distributors in their area but speak with them only to find out if Indians are due in town anytime soon. “There’s really not much to talk about,” Arnoldo shrugs. Meanwhile, without naming names, Isabel Lopez hints darkly that black-marketeering and forgery of DEA forms can and does occur. Armando Reyna insists that can’t be true; there’s just not enough money in peyote.

“Maybe once in a while some unlicensed people go pick some and sell it to the Indians who come to town, but when they do, it’s because they’re out of a job,” Armando explains. “It doesn’t happen much, and as soon as it gets to be melon season or onion season, they’ll go back to the sheds.”

As Armando speaks, he bundles up a shipment for Canada. Wrapping the box in brown paper, he writes the DEA and DPS permit numbers on the side of the parcel. On the customs declaration he writes simply “1,000 buttons peyote.”