There had been close presidential elections before—in 1960 John F. Kennedy beat Richard Nixon by fewer than 120,000 votes—but in 2000 Texas governor George W. Bush did something that no one had done since the Benjamin Harrison—Grover Cleveland race of 1888: He lost the popular vote, to Vice President Al Gore, but won the electoral college, to become the forty-third president of the United States.

The election centered primarily on domestic issues: taxes, the budget surplus, Medicare, Social Security (remember Gore’s “lockbox”?). Yet after eight years in office, Bill Clinton had damaged his presidency—and the candidacy of his vice president—with the Monica Lewinsky scandal. Bush, vowing to “restore dignity and honor” to the White House, appealed to voters turned off by Clinton’s personal excesses.

On Election Day, November 7, the race was extremely close. Of the battleground states, Florida was a particular target for the Republicans. Though Clinton had carried it in 1996, four years later, Bush’s younger brother Jeb was the governor, and the family joked that it would be a quiet Thanksgiving if he couldn’t deliver its 25 electoral votes. But before the polls had even closed, the television networks gave Florida to Gore. A few hours later, they reversed course and gave it to Bush. Then they backpedaled completely and left the campaigns—and the nation—unsure of the endgame.

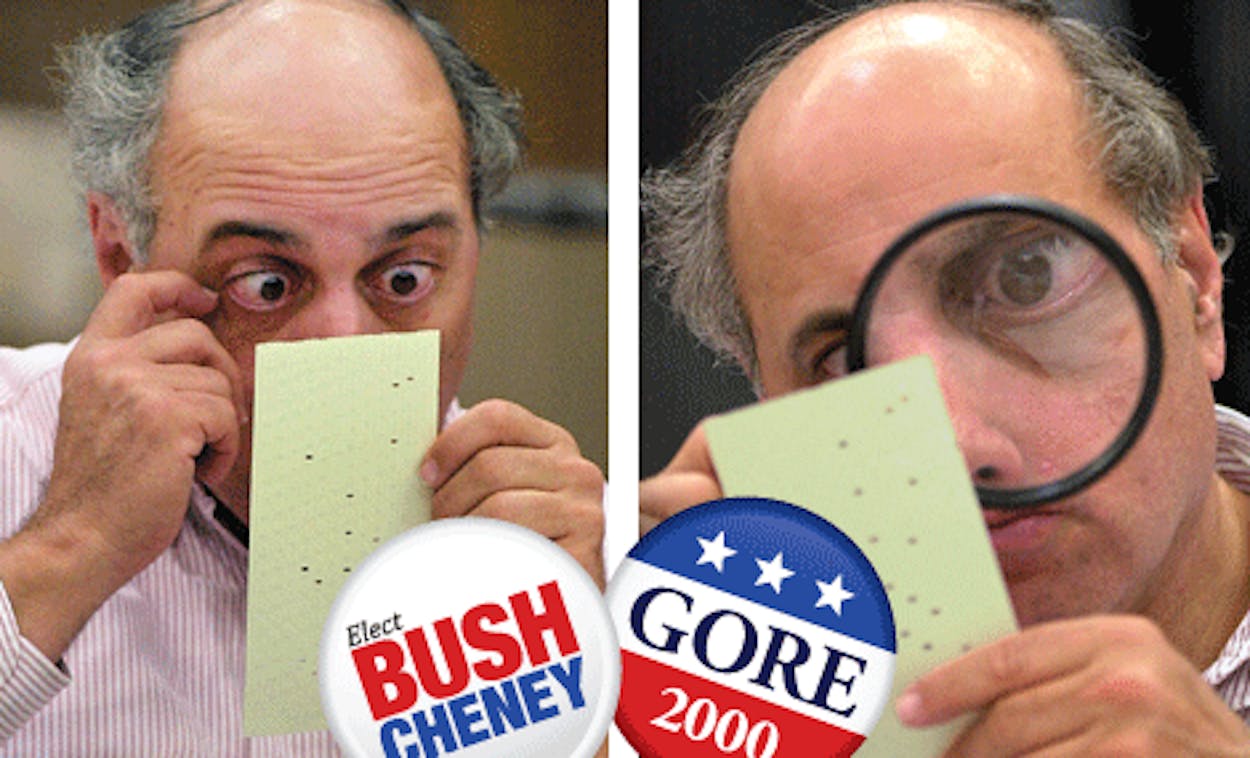

In the ensuing saga of the recount, the country learned about chads (pregnant, dimpled, and hanging), butterfly ballots, and the discrete charms of Florida Secretary of State Katherine Harris. Finally, the U.S. Supreme Court intervened—another unprecedented twist—and sealed the victory for Bush. History hung on a mere 537 votes.

When Bush gave his first address as president-elect, on December 13, the nation had no idea of what lay ahead: September 11, Katrina, the global economic meltdown. Very few Americans had ever heard of Al Qaeda, let alone Osama bin Laden. Eight years later, the world is a very different place indeed—but the memories of those 36 days loom large in the minds of the Texans who lived them.

“ ‘We Are Headed for a Great Night.’ ”

On Election Day, the poll numbers were tight, but some bad news had hit the previous Thursday: The media reported that the governor had been arrested in 1976 for DUI. No one knew how that would affect the outcome of the race.

JOE ALLBAUGH served as Bush’s campaign manager in 2000 and was the director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency from 2001 to 2003. He is the president and CEO of the Allbaugh International Group, a consulting firm based in Washington, D.C. You work an entire campaign for Election Day. You show up early to make sure that the apparatus you’ve put in place is functioning, whether it’s poll watchers or phone banks or drivers to get out the vote. It’s checking with your team members all day long.

MATTHEW DOWD was a senior strategist for the 2000 Bush-Cheney campaign and the chief strategist for the 2004 campaign. He is a founding partner of ViaNovo, an Austin-based branding firm. I played golf that morning at Circle C in Austin with Dan Bartlett and some other folks. I had golfed on Election Day when I worked on Democratic campaigns, and it had become a tradition. It started to rain and then it got sunny and then it started to rain again. I thought, “Is this a harbinger of tonight? You think it’s clear, but it’s not?”

DAN BARTLETT, a senior spokesman for the 2000 campaign, served as White House communications director from 2003 to 2005 and counselor to the president from 2005 to 2007. He is a senior strategist with Public Strategies, an Austin-based consulting firm. Neither of us shot that well, but it was good to get a break from all of the nervousness.

MINDY TUCKER FLETCHER was Bush’s national press secretary in 2000. She lives in San Diego, California. On Election Day I felt helpless. As a press person, there wasn’t much to do, though it’s not that way anymore because of these massive turnout operations. So I slept in and went to the office late.

LINDA EDWARDS GOCKEL was Governor Bush’s communications director in 2000. She is a consultant with Vollmer Public Relations in Austin. I knew it was going to be close, but I felt good about it. How could you not? The governor was always so upbeat. Mindy had sent out a note to [the press team] the night before that said, “I know this was in the AP story today, but Karen [Hughes] wanted me to share this story with everyone. The governor asked her how she felt about things and whether she was nervous. She told him that she felt serene. She knows that we have run a good campaign, given it our absolute best, and now it is in the people’s hands. He said, ‘I agree.’ We are headed for a great night.”

DANNER BETHEL was a policy analyst for the 2000 campaign and the deputy chief of staff at the U.S. Department of Education from 2001 to 2003. He is a managing director at Public Strategies in Austin. The policy shop decided to have lunch at a bowling alley and take it all in. In the seventh frame, [future White House chief of staff] Josh Bolten got a page—we had pagers back then that displayed text—with the first exit polls. They were disheartening. We quickly wrapped up the bowling session and headed back to our headquarters, at 301 Congress. We were still cautiously optimistic, but the tone had totally changed.

DOWD: Because of the disclosure about Bush’s DUI arrest, we did some polls that we normally wouldn’t have done on Sunday and Monday and got numbers back that morning. We went from a three- or four-point lead in Florida to dead even. In Michigan we went from even to three or four points behind. And Ohio went from four or five up to one or two up. My sense was that we were going to have a long night.

BARTLETT: The types of conversations I had with the national media began to change. You’re talking in soft undertones and whispers. They’re not quite saying, “We’re sorry that you’re going to lose today,” but that’s the background music.

DONALD EVANS was the campaign chairman in 2000 and served as U.S. Secretary of Commerce from 2001 to 2005. He lives in Midland, where he is the nonexecutive chairman of Energy Future Holdings. Around seven o’clock, the Bush family and some friends gathered at the Shoreline Grill for dinner. Before we even sat down, Florida went for Gore. For that state to go into Gore’s column so early was a huge blow, so no one really stayed to eat. The president and his immediate family went to the Governor’s Mansion, and I went to the Four Seasons with a lot of other people, where we ground out the numbers all night long.

JAMES A. BAKER III, a close Bush family friend who served in three presidential administrations and was Secretary of State for George H. W. Bush, oversaw the Florida recount for the Republicans. He is a senior partner at Baker Botts in Houston. We were staying at the Four Seasons, where the Cheneys were staying. I remember watching the returns with Dick and some of his other close friends—[1996 Republican vice-presidential nominee] Jack Kemp was there—and as things dragged on, it was obvious that Dick was very tired. We said, “Hey, why don’t you get some rest?” He did. I think he went in and took a nap, probably through some of the misreporting of the results in Florida.

BARTLETT: A lot of us were camped out in Matthew’s office, trying to pore over the numbers in Florida. First it was on a county-by-county basis. Then it was at the precinct level or even the neighborhoods. We were running back and forth trying to get more evidence to use with the media to say, “Don’t call this. Don’t call this.”

FLETCHER: I will never forget the moment that Karl [Rove] came running into my office, screaming, “Get on the phone with NBC right now and tell them they called Florida before the polls had closed.” That was a wake-up moment. From that time on, everything changed. So I got on the phone and started yelling at people.

BARTLETT: You think that if they say it on TV, it must be true. We still had confidence in our modeling, yet there was real trepidation.

“ ‘It’s Like a Big Ship With a Hole in the Hull . . .’ ”

At 9:13 p.m., the networks began to retract their call in Florida, prompting CBS anchor Dan Rather to note that the race was “hot enough to peel house paint,” adding, “If a frog had side pockets, he’d carry a handgun.”

MARK MCKINNON was the media and advertising director for the 2000 and 2004 campaigns. He is the vice chairman at Public Strategies in Austin. When you’re in a campaign, you have a way of occluding reality and finding really creative ways to hang on to hope. Matthew and Karl were coming up with bizarre electoral scenarios that had us winning states that we weren’t going to win. Then when Fox announced that Bush had won Florida, at about one-fifteen in the morning, it came from out of nowhere. I was so excited I grabbed the closest person to me and kissed her, and it happened to be Bartlett’s wife. I remember him going, “What the hell?” But I had to grab somebody.

EVANS: About one-thirty a.m. I received a call from [Gore campaign chair] Bill Daley, and he said that we’d be hearing from Vice President Gore in a few minutes. He was talking to his family, and as soon as he finished, he was going to call the governor. I was still in the suite at the Four Seasons. As I waited, we watched Florida collapse.

BAKER: We were told that Gore had called and conceded and that Bush was going to go to the Capitol, where he was going to give his speech outside. So we started heading for the exits to go to the site, but it was raining like hell and it was sort of chilly. I had a cold, and I remember waiting in the porte cochere of the hotel for the shuttle bus. I told my wife, Susan, that I had second thoughts about going and standing in the rain and the cold. So I went back up to my room and watched the television reports for another hour or so before going to bed.

DOWD: When they initially called Florida for Gore, I said, “The networks called it way too early.” Then they called it for us, and I said, “They called it too early again.” But I remember walking up Congress Avenue to the Capitol and thinking, “It must be fine because the networks wouldn’t get it wrong twice.”

EVANS: I left the Four Seasons and met Governor Bush on the back porch of the mansion. We embraced each other, and I congratulated him, thinking, “We won this thing. Unbelievable.”

FLETCHER: I remember us all tearing down Congress to hear the speech. I was hanging out with Dan, and we were doing the “W” sign with our fingers. Then we realized it was taking too long. I started calling [aides] Gordon Johndroe and Logan Walters, and I was getting these cryptic messages back: “It’s not going to happen. He’s not coming.”

EVANS: Bill Daley had called me back and said, “We’ve got a problem.” I think Florida was down to 1,800 or so votes, and no one was in a position to call the state. The governor was cupping his ear to the phone to hear what he was saying. But you have to put yourself on the other side. You’re not going to give away an election that you might rightfully have won. You couldn’t do that to your supporters. So I called the Secretary of State in Florida, Katherine Harris, who had the authority to declare a winner. She wasn’t in her office, so I asked, “Where is she?” I was told that she was at home. So I asked for her number and called her and said, “I’m assuming that you know what’s going on. What are you doing?” I don’t remember exactly what I said, but there was a very high level of frustration. It was after that phone call that I realized that we weren’t going to get an answer that night.

BARTLETT: As the time dragged on, we grew wearier, and then Don Evans came out and announced that Florida was too close to call. So we all headed back to headquarters. That’s when the weather changed. It was so ominous. It felt biblical, to say the least.

EVANS: After I got off the stage at the Capitol, I went back to the mansion, then decided that I was going to get a couple of hours of sleep at my apartment. I walked into the lobby, but I changed my mind and went to the office instead. Ben Ginsberg, the national counsel for the campaign, was there, and we started sending lawyers to Florida. I called the governor and asked, “What do you think about sending Baker?”

FLETCHER: My boyfriend at the time had promised me a vacation after the election, and as things started going south that evening, he began giving me little bits of the surprise, thinking it would make me happy. It ended with him finally telling me that we were going to Florida. I had no idea that I was going to Florida anyway.

BARTLETT: As our numbers were deteriorating, I think Matthew used this analogy: “It’s like a big ship with a hole in the hull, and we’re trying to get to the dock before we sink.” He and I had gotten pretty down about the numbers. My wife was sitting on the edge of a desk in Matthew’s office, and she wouldn’t move. It was almost like, as long as she sat there, we would get good news. I finally had to persuade her to get up and come talk to me privately, and that’s when I told her that I thought we were going to lose. She got mad at me and said, “You can’t be defeatist.” But I was trying to prepare her for the letdown, while everyone in there was trying to rah-rah it on.

ALLBAUGH: I don’t remember what time I got home that night, but my daughter, Taylor, who was fourteen at the time, said, “Daddy, is the governor going to be the president in the morning?” And I said, “Darling, you just go to bed, and when you wake up, he will be the president.” I got it right, but unfortunately it was 36 days later.

FLETCHER: We decided that half the [press] team was going to stay up and half would go to sleep. I remember lying in my bed at three o’clock in the morning with my cell phone ringing and my home phone ringing. Everyone was asking, “What do you know?” And we didn’t know anything. The press didn’t know anything. No one did.

“If That’s Our Legal Team, We’re Screwed.”

With more than 5.8 million ballots cast in Florida, Bush led Gore by only 1,784 votes the next morning. Because the result was less than one half of one percent, state law required an immediate machine recount. Though Gore had won the country’s popular vote, the entire election centered on Florida’s 25 electoral votes.

ALLBAUGH: The next morning we had a very early staff meeting, and there was a serious discussion about Don Evans calling Jim Baker, which he did.

BAKER: When I got up the next morning, nothing had been resolved. I had an appointment back in Houston, so Susan and I flew to Hobby Airport on a private plane and got in a car to go to the office. I think it was about eight-thirty when I got a call from Don Evans, saying, “We’re thinking about asking you to go to Florida.” By that time I had heard that Gore had asked [former secretary of state] Warren Christopher to go. Don said, “Would you be in a position to do that if the governor wanted you to?” I was supposed to go to England to shoot pheasants with 41, but of course I told him that I would.

FLETCHER: I came in the next morning, and I remember Karen saying, “This is going to be over in a couple of days, so I don’t want any of you guys to leave.” Come Saturday morning, I still had all of my clothes out for my vacation, totally in denial.

DAN BRANCH headed up Americans for Bush-Cheney, a group of Democrats, independents, and cultural leaders who supported Governor Bush during the 2000 campaign. A Republican member of the Texas House of Representatives since 2003, he lives in Dallas. I got a call from [future White House counsel] Harriet Miers at about ten that morning. Basically she told me, “We need to find lawyers who can go to Florida.” So I schlepped up to 301 Congress, and I remember the scene on the ground: a lot of staffers on the floor with maps of Florida. And I’ll never forget seeing a bunch of faxes with names of lawyers just pouring out of the machine and falling onto the ground.

BARTLETT: The morning was combination pep talk and marching orders. We were making it up as we went. There was no blueprint. But you could see that the lawyers were becoming the more prominent decision-makers. Everything was turning into a legal strategy.

ALLBAUGH: We headed over to the mansion. The Cheneys, the Bushes, Karl, Karen, Don, and myself were there. The governor asked, “Do we know for a fact that Jim Baker will go?” And Don said, “He will if you want him to.” The governor said, “Let’s make it happen.” Don stepped into the library and called Jim and told him that I’d be in touch.

BAKER: A little while later I got a call saying, “We’d really like you to do this, but there’s some time urgency. If you can do it, we’ll have a plane there by two o’clock this afternoon. Joe Allbaugh will be on it, and you and he can go over together.”

ALLBAUGH: Secretary Baker asked, “How many days should we pack for?” I said, “I really don’t know, but three ought to be enough.”

CLAY JOHNSON III was the chief of staff for Governor Bush in 2000. He is now the deputy director for management at the Office of Management and Budget, in Washington, D.C. The most unbelievable thing that I heard that morning was when Don Evans said, “You guys”—pointing to a group of eight or so people—“go to the airport and get on a plane and we’ll tell you what to do en route.” So they got on a plane to Florida and landed at the first city. One of them was told to get off and that someone would find them in the lobby. Then the plane flew on to the next city, and it was the same thing. That’s how the entire recount went. You just put a bunch of people on the field and then figured out what plays you were going to call.

ALLBAUGH: When we got on the plane to Tallahassee, the first thing Secretary Baker said was “Give me a rundown of the state. What have you been doing, and what’s in place?” So I spent the next thirty or forty minutes briefing him, and I will never forget that the second I finished, he said, “Well, Joe, we’re headed to the U.S. Supreme Court.” He knew at that moment. I said, “Really?” And he said, “Absolutely. There’s no other way this will be resolved.”

BAKER: From day one it was my view that if the final arbiter of this dispute was the Florida Supreme Court, we were toast. When I was Treasury Secretary during the Reagan administration, [Democratic U.S. senator] Lawton Chiles [of Florida] was the chairman of the Senate Budget Committee, and I worked very closely with him. We became friends primarily because we both liked to hunt turkeys. Through those experiences I knew the type of people he had put on the Florida Supreme Court when he was governor, and I had met his number one adviser in picking those people. His name was Dexter Douglass, and he was on the Gore legal team. In fact, he later introduced [Gore’s lead lawyer] David Boies to the Florida Supreme Court.

ALLBAUGH: The flight time was two hours, and we landed in the late afternoon. I called my guys on the ground and said, “You’re going to pick up the Secretary and myself here. Then we’re going to go to the hotel,” which was the Doubletree in downtown Tallahassee. Our guys showed up in this ratty old Ford Escort, and I about had a heart attack. Here we had a former secretary of state, and the best we could do was a Ford Escort with a busted muffler. I said, “This is a bad sign.” After we got checked into the hotel, Secretary Baker said, “I want to go see Jebby.” That’s the way he referred to Jeb, because he had known him since he was yea high. Jeb kept saying that he was going to remain the governor for all Floridians. He said, “I don’t want to know what you’re doing. I just want to know that something positive is happening.” You could tell he was anxious. Then we went to the state party headquarters. Ben Ginsberg was there, and he chaired a meeting with a lot of local lawyers. The Secretary said, “Tell us what’s going on.” He wanted to know in detail who we had on the ground. It was a long meeting, and afterward—Ben notwithstanding—I turned to the Secretary and said, “If that’s our legal team, we’re screwed.”

BAKER: The Gore team was far better prepared to deal with a recount. Were there times when we thought we could lose? You bet. But by the end of it, I was managing the largest law firm in the country.

ALLBAUGH: Later that night I got a knock on my door at the Doubletree. It was Bob Zoellick and Margaret Tutwiler, two of the Secretary’s closest confidants, and they wanted to meet in the Secretary’s room. So I re-dressed and headed down there. He had changed clothes as well, and his pants were on the back of the chair. Margaret picked them up and said, “Can you hang these?” So I got a hanger. And Bob and the Secretary were talking, and she said to me, “Now, listen, the Secretary is very finicky. He likes to have them folded along the crease.” The Secretary looked at Margaret and said, “Joe knows how to fold a pair of pants.” It was surreal. We were worried about the presidency of the United States, and Margaret Tutwiler was trying to teach me to hang a pair of slacks.

GOCKEL: On the Thursday morning after the election, I had to go to the mansion for a meeting with the governor to discuss state business, and I remember thinking, “How shall I greet him?” Here’s a man I’ve grown close to over the years, and he’s going through something that no one could have possibly imagined. For the first time in three years, the governor’s spokesperson was speechless. When I walked in, the governor was standing in the library. He said, “Hello, sweet Linda!” “Sweet Linda” was the closest I ever got to a nickname. So I replied, “Here’s a man I’d like to hug.” And he said, “Watch out for the boil.” Remember that boil on his face? He didn’t have a bandage on it that morning, and it was really huge and really disgusting. It was almost like this physical manifestation of stress.

DOWD: Austin was a total fog. It was like flying an airplane without instrument lights in a storm. You’re already exhausted and you think you’re going to catch up on sleep. The people who knew the most were the ones on the ground, not the ones at headquarters.

ALLBAUGH: The next morning we went to the [Florida Republican] party headquarters and got the Secretary an office. We started moving people out of their offices, and at the end of the 36 days, we had totally consumed that building. We had to start feeding people and taking care of them. It was like running an army: setting up laundry service and carpools and getting everyone housing. Of course, after day three, my wife, Diane, had to overnight me fresh clothes.

BAKER: We went to see Katherine Harris, just like the Gore people had. My impression was that she was someone who would try to do her job in the best way that she could. Even though she had been the co-chairman of the Bush effort in Florida, she was not someone whose strings we could pull on the issues involving certification. In fact, we initially had some differences with her on whether she was ruling the way the law required her to, and I know the Democrats did too.

ALLBAUGH: I’m not sure that Katherine Harris knew at that point the ramifications of what was going to happen. We left with a clear idea that she didn’t have a clear idea. As the Secretary and I walked out of her office, the media was just swarming everywhere. We didn’t have any security; it was just the two of us. And I’m thinking, “This is going to get out of hand really fast.” We had to take an elevator to get to our car, and somebody tried to follow us in with a camera and lights. I got ahold of the lens, pushed back, and said, “No, you’re not.” The Secretary said, “Thank you, Joe.”

“ ‘Joe, You’ve Got a Hell of a Problem Here.’ ”

On Friday, November 10, the automatic machine recount ended. Though official results were not released, with 66 of the state’s 67 counties reporting, Bush’s lead had shrunk to 960 votes. Palm Beach and Volusia counties had agreed to conduct hand recounts, and the next day the Republicans would file the first suit on behalf of a campaign in U.S. district court to stop them.

BAKER: We had a lot of debate about that internally. Even though we were ahead, I thought we should file the first lawsuit. We had some people say to us—including, in fact, [former Missouri senator] Jack Danforth, someone I was going to recruit to be one of our federal court counselors—“You can’t do this. George Bush is young enough to run again. This will ruin his chance if you file this suit.” But I previewed the strategy with the governor and with Dick Cheney. They said to go ahead.

FLETCHER: On Saturday morning we were watching a guy hold up a ballot on TV. Later we were in the conference room, and I remember thinking, “They’re going to take this away from us. I cannot just sit here in Austin and watch this happen.” I had that moment of realization that we were about to get our butts handed to us.

ALLBAUGH: What we found in the Sunshine State was, there was no uniformity. Not only did the law vary from county to county, it varied from city to city. You had to start at the lowest level of political organization, and there were the four counties. Fortunately, we had great people there, like Pat Oxford, of Houston.

PATRICK OXFORD headed up a team of volunteers during the election called the Mighty Texas Strike Force. He is the chairman of Bracewell and Giuliani, a Houston-based law firm. Governor Bush had put me on the board of regents for the University of Texas System, and we had a meeting in Tyler after the election. I was told I had an emergency call, so I stepped out, and it was Joe. He said, “I’m having some problems in Broward County. Would you mind going down and helping with the count?” So I took a small plane owned by UT, flew to Dallas, met up with some other guys, and headed to Fort Lauderdale.

BRANCH: The campaign asked me to go to Palm Beach, home of the infamous butterfly ballot. I stayed at the same hotel Jesse Jackson was staying in, and all these people from both sides would go through the buffet line together for breakfast. I remember asking the Reverend Jackson, “What are you doing down here?” And he said, “I’m picking the leaves off the Bushes.”

FLETCHER: I’m a huge sports fan, and I ended up on a plane to Tallahassee with all of these sportswriters. They were going to the Florida–Florida State game on November 18. One guy on the plane asked me, “Do you have a hotel room?” I said, “Oh, I’ll just show up and find a place.” And he said, “Well, people have made reservations for the game, and they’re not going to give them up.” And I remember thinking, “Who wins out here? The political people or the football people?” Of course, it was the football people.

ALLBAUGH: I went to Al Cardenas, the state party chair, and told him that we needed to move people out of the Doubletree fast. We moved en masse across the street to a less-than-spectacular apartment unit.

FLETCHER: We stayed in these little trashed-out apartments right across from the party headquarters. After that, we stayed in a Days Inn or a Holiday Inn, and I’m really surprised we all survived it. Someone’s room caught on fire. Another friend had a shower curtain left on her bed, and when she called to have it put up, the woman told her, “We don’t really like your type here.”

ALLBAUGH: Finally we had the IT support, and we had the communications going. Now we had to round out Ted Olson’s legal team. He was heading up the federal court cases. He came to me and said, “Joe, I don’t want to ask for much, but can you try to find me a quiet place to think?” So I found this closet down on the first floor and said, “This is the best I could do.”

OXFORD: At about ten or eleven I went to the hotel and went to bed. The phone rang, and it was Allbaugh. He said, “Pat, I need you to go down to the bar and meet the people who are running the show there in Fort Lauderdale.” So I pulled on my pants and went down there. These guys had apparently been in Florida since Election Day, and they were just out of juice. In my mind’s eye, I can see them literally crying in their beer. It was just discouraging. So I told them, “Will you excuse me for a minute?” and I went back to my room, called Joe, and said, “Joe, you’ve got a hell of a problem here. Your guys look ready to throw in the towel.” Joe asked me to step in, so the next morning I got up real early and met with all of these young volunteers. In the Army in my era, if you didn’t go to Vietnam, you weren’t going to get promoted. Well, in very rough terms, that’s the way the recount was. All of these kids who had gone to Washington right out of college swarmed down to Florida to be on the scene. On the first day I had about fifty of them. Only one was actually being paid by the campaign—all the rest were volunteers.

ALLBAUGH: We had local fights going on in the counties, and local suits were being filed. Every minute of the day was consumed by either watching a media report or sitting with the lawyers and trying to figure out who’s on first.

OXFORD: I had never heard the word “chad” spoken before. No one had. These were just punch cards, and we were trying to interpret cases where the punch did not go all the way through, if it was really a vote. It was during that period of time that the process of counting the votes became the process of attributing votes to people: What were they really thinking? This guesswork seemed as ridiculous then as it does now. For example, there was a group of 52 ballots that came in a bunch that had obviously been punched out for Bush, but then the punch had been put back in and another punch was made for Gore. The Democrats argued that all of the voters had made a mistake and redid their votes. If that had been the case, you would have 52 differently done retapings, but these looked like they had been precisely done by the same eye surgeon. That was the kind of hand-to-hand political combat you were going through.

BRANCH: We were in the county’s emergency operations center—the hurricane facility—and that’s where we ended up advocating our position. We were trying to get as many of our ballots in as we could, and they were trying to get in as many of theirs. Sitting right in front of the three judges, we would literally take up each ballot and make the case. They’d show it to each side and they’d want to hear your arguments and [your opponent’s] arguments, and then they’d make a ruling. Once, I saw a ballot that was in a plastic baggie, still soggy from being exposed to water.

OXFORD: Picture a big auditorium with forty or fifty tables. Each table had three people sitting at it—a Democrat, a Republican, and a city or county official to observe the count. Keep in mind, the first morning we had county commissioners and the like acting as observers, but as time went on and this got to be sort of a boring process, any county employee would work. At the end of the day, we literally had garbage collectors acting as official observers supervising the recount. There was one big box of punch-card ballots for every precinct in Broward County, and when a team was ready, some official would bring a new box to the table, and the teams would look at each and every punch-card ballot in that box. The county observer would hold them up, and the Republican and the Democrat at the table would either agree or not. If they didn’t agree, the observer would put it in a special pile. This went on and on, and eventually all of the “special pile” votes would go before the county election commission, which was a tribunal of a Republican, a Democrat, and a neutral judge. That’s how we recounted all 597,000 votes in Broward County.

BAKER: I will never buy the argument that the Republicans controlled the elections in Florida because we had the governor and the Secretary of State. The truth of the matter is that the people counting the votes were mostly Democrats. And the butterfly ballot was written by a Democrat. That’s why we had a sign on the wall at our headquarters: “Those who cast the votes decide nothing. Those who count the votes decide everything.” That was something Stalin had said.

OXFORD: After the counting of the “special pile” votes was moved to the county courthouse, I’d speak with Allbaugh, Karl Rove, Don Evans, or other campaign leaders up in Tallahassee every day. To have a conference call with them, I’d have to go to a stairwell to talk because it was so loud. Up in Palm Beach and Miami-Dade, they were reacting to court decisions. As the other counties all fell by the wayside, we were it. As I joked at the time, I felt like I was going to be this footnote in history, sort of the Bill Buckner of the 2000 campaign: “Who was that incompetent idiot from Houston who let the election get away in Broward County, therefore losing the state, therefore losing the presidency?”

“Manna From Heaven”

On Wednesday, November 15, Vice President Gore appeared on national television and said that if the Bush campaign would agree to hand recounts in Palm Beach, Broward, Volusia, and Miami-Dade counties, he would drop any other legal challenges.

BARTLETT: We didn’t mind the contrast that evolved between the two candidates—reports that Gore was e-mailing lawyers as they were going in to make presentations while Bush was showing a degree of confidence in his team. But when Gore appeared on national television, it was a moment when Bush needed to return to Austin from his ranch, in Crawford, to provide an on-camera response. He said, “Why don’t I just come down?” He gave a statement saying that hand recounts could only introduce errors and that all of the votes had already been counted at least twice. It was a huge strategic blunder on the part of the Democrats to want to cherry-pick counties. So I worked on a statement with Karen to make that point.

EVANS: I stayed in touch with Governor Bush to let him know what was going on, and he spent a lot of time in Crawford during that period, just relaxing and fishing or whatever. I went up there a couple of times, but it wasn’t to strategize. It was about friendship and staying close. He was relying on his team to do whatever needed to be done—unlike Cheney, who was always focused on that TV.

BARTLETT: When Bush went back to Crawford, I remember talking to him early one morning. He said, “Well, we could be in Gore’s place.” Better to be in the lead than playing catch-up.

BAKER: They gave us the moral high ground when they asked for hand recounts in only four counties, the big Democratic counties. That was manna from heaven. That totally eliminated their “count all the votes” argument.

“You’ve Got to Be Kidding.”

On Friday, November 17, the Bush campaign obtained the so-called “Mark Herron memo,” named for a Democratic lawyer who had made the case for how the Gore campaign could exclude overseas ballots that did not bear a postmark.

BRANCH: At some point I asked, “What happens to the overseas ballots?” thinking that could be the difference in the outcome. We knew that in ’96 Dole had gotten about 60 percent of the overseas ballots. If we won the overseas vote, that would be really important with such a close count.

ALLBAUGH: That Friday a good friend of mine by the name of Warren Tompkins, a longtime party operative from South Carolina, walked in and said, “Joe, I think we’ve got something here.” Two of his friends had stumbled across this memo. As Warren was talking, I said, “You’ve got to be kidding me!” Finally I said, “Give me that.” And I started reading it, saying, “You’ve got to be kidding me!” So I took it to Mindy and said, “We’ve got to get this out.” I thought, “This is the way the Democrats want to play? They don’t want to count men and women in uniform?”

FLETCHER: There’s a really good AP picture of me as I start handing it out, and I’m surrounded by microphones and cameras and people reaching in to get a copy. In that environment, it was easy to make news because people wanted the next big thing in the story.

BRANCH: I went to the postmaster in Palm Beach and asked, “How do the military ballots work?” He said, “They come into New York and San Francisco and Miami from our military bases, and they get dumped into the system. They still show up even if they don’t have a stamp on them.” And I said, “Well, how does that work?” He told me, “You know, the buck private is the mail guy, and at some point the ship is coming for the mailbag, and he puts away his stamp. But someone runs up and says, ‘Oh, wait! I’ve got to get this to Mom.’ So they open the bag up and they stick it in. And over time, they’ve learned that these things still get to Mom or their girlfriend or their spouse without the stamp.” Ultimately Vice President Gore got on the wrong side of this thing, saying these unstamped ballots should not be counted because of a technicality. As a lawyer, I understood his argument, but I also saw that the public relations angle of denying servicemen and servicewomen their votes was terrible for them.

ALLBAUGH: I was focused on Florida and had no idea that [Gore’s running mate] Joe Lieberman was going to be on Meet the Press that Sunday. When he told Tim Russert that he thought their campaign should “go back and take another look” at the attempt to exclude the military ballots, that opened the barn door. You know the expression “It’s better to be lucky than good”? We were lucky that weekend. That was one of the initial turning points for us. Up until that point, I was doubtful.

JOHNSON: That weekend we had dinner at the home of Tim and Mary Herman, who had gotten to know the governor and Mrs. Bush because they have a child who is the same age as the [Bush] twins. The governor was composed and enjoying everyone’s company. Everyone else was more wound up. At the end of the meal, the governor said he wasn’t going to open his fortune cookie, so my wife, Anne, did it for him. She read it out loud: “You are entering a time of great promise and overdue rewards.” Laura said, “You’ve got to be kidding!”

“ ‘Lord, It’s Wayne.’ ”

On Tuesday, November 21, the Florida Supreme Court ruled unanimously to extend the deadline set by Secretary of State Katherine Harris to accept hand-counted ballots.

BAKER: How’s that for legislating from the bench? It was legally unconscionable. And by the way, that’s what the U.S. Supreme Court essentially said when it later remanded the case to the Florida Supreme Court. So I called a press conference and was pretty tough. I said, “Two weeks after the election, that court has changed the rules and has invented a new system for counting the election results. One should not now be surprised if the Florida legislature seeks to affirm the original rules.” I thought maybe we ought to use the neutron bomb, which was the ability, constitutionally, for the Florida legislature to pick the delegates. That was just a suggestion, that we had that arrow in our quiver.

OXFORD: In that period of time the Democrats sent down David Boies, who is a topflight lawyer, to argue the validity of various ballots in the “special” pile. David has this little trick—he finds a case that’s relevant and memorizes some obscure footnote in the opinion, and when he came forward to talk with these local judges, he might say, “Well, I remember a case that I once read that was right on point here, and I think it was on page two hundred eighty-one—maybe in a footnote.” Then he quotes it verbatim. Well, it’s the oldest trick in the book, but it really works with these judges. They obviously thought, “This guy is a genius. He must really know his stuff.”

FLETCHER: Thanksgiving was two days away, and I was supposed to be in Virginia with my family. Instead I was on television in Tallahassee. Secretary Baker was our top-level spokesperson, but you didn’t send him out every day. So I would make the rounds on cable TV two or three times a day. My counterpart for the Gore campaign was from Tallahassee, and he was living at home. His mom was cooking for him and doing his laundry. Well, at least my mom sent me Rice Krispie treats.

ALLBAUGH: Jim Baker wanted to go home the Wednesday night before Thanksgiving, and I was looking forward to it. I was whipped mentally and physically. Don Evans had agreed to come to Florida and keep watch over things. But my daughter was really put out with me. Taylor met me at the door and said, “I’m not even sure why you came home, Dad. I know you’re just going to turn around and go back to Florida.” It was just a dagger in my heart, but she was right. The next morning was Thanksgiving, and I was on the phone with Florida. And on Friday morning at nine o’clock I picked up the Secretary, and we flew back to Tallahassee.

BARTLETT: I spent Thanksgiving with my wife’s family in Austin. They ate at the Austin Country Club, and I spent dinner on the phone outside.

OXFORD: We counted ballots all day on Thanksgiving. We were really dragging, but afterward someone had decided to host a turkey dinner for all the volunteers in Fort Lauderdale. [Then–Montana governor] Marc Racicot and I got our food and sat down. Everyone was eating and minding their own business, and suddenly in came Wayne Newton with a couple of young ladies. The emcee called on him to give the invocation, and Racicot and I—both good Catholic boys—looked at each other and thought, “What the hell is this?” So Wayne went up there, and of course his hair looked like a football helmet. Old Wayne has this method of praying that is sort of like talking directly with the Lord. It’s not “My Father.” It’s “Lord, it’s Wayne.” So he started talking to the Lord and giving a review of the history of the Republican party, and as we were standing up we started to shift from foot to foot because he went on for a long time. We were trying to pray, but it was hard to keep a straight face. Then we were all asked to sing “Danke Schoen,” Wayne’s anthem from the early sixties. They passed out these mimeographed sheets with the lyrics, but 90 percent of my team had never heard of the guy. So there we were, and Wayne tried to carry this rendition of the song. It was this Mad magazine kind of scene that you couldn’t make up.

“ ‘Oh, My God! Mindy Totally Took on Jesse Jackson.’ ”

On Friday, November 24, the day after Thanksgiving, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear Bush’s appeal to stop the hand counts. For all practical purposes, the election now hinged on the battle between the U.S. and Florida supreme courts. On December 4, the U.S. Supreme Court set aside the ruling to extend the deadline, but four days later, the Florida Supreme Court issued a new decision that ordered an immediate statewide manual recount, leading to another confrontation with the country’s high court.

ALLBAUGH: The first Supreme Court [hearing] was amazing. I had never heard arguments before the high court. David Boies would make his presentation, then we would go. We ended up sharing this same room for press conferences. Originally there was just a blue curtain for a backdrop, so we put flags up. Then someone took the flags down, so we put them back up. It was chaos.

FLETCHER: I got a break from Florida twice, when I went to D.C. for the Supreme Court hearings. I flew with Ben and Ted. Everyone had a good sense of humor. Ben is hilarious, and that kept everyone really lively. There were all of these attorneys who were having a ball.

BAKER: I didn’t go to the arguments before the Supreme Court because I had been involved in the appointments of some of the justices. But that Sunday, Katherine Harris certified Bush as the winner of Florida by 537 votes. Certification changed the landscape. The Gore campaign was no longer protesting an election count. It was contesting a certified election.

ALLBAUGH: The Florida Supreme Court ruled again and said, “Start the count,” so we literally mobilized six hundred people overnight. All night long, our campaign political director, Ken Mehlman, was conducting training classes: This is what you do, this is where you go. They were going to start counting the following morning.

BAKER: Florida chief justice Charles T. Wells’s dissent from his own court regarding the statewide recount points out the legal and political arguments that we were making from day one. The court’s majority ruling was outrageous. The U.S. Constitution says that the legislatures of the various states shall determine how presidential electors are selected, and the Florida Supreme Court substituted its judgment for the Florida legislature’s. Why did the U.S. Supreme Court stay the judgment of the Florida Supreme Court? They did it because they told the Florida Supreme Court the first time they remanded the case, “Explain to us how you got here in the face of the U.S. Constitution.” The Florida Supreme Court came back with this four-to-three decision and never even acknowledged the U.S. Supreme Court. Well, that might well have been designed to piss off the members of the higher court, and I think it did. And in my mind, I think it was one of the reasons that we got a stay. A lower court should never stick its thumb in the eye of a higher court.

FLETCHER: After the second hearing at the U.S. Supreme Court, there was a place with a microphone and the press outside, and every [politician] was there trying to get his place in the sun. There was a line, but I had the guy who had just argued in front of the Supreme Court. So I explained to Jesse Jackson that we were next. Ben made this joke, “Oh, my God! Mindy totally took on Jesse Jackson.”

“Congratulations, Mr. President-elect.”

The U.S. Supreme Court issued its final 65-page ruling in Bush v. Gore on December 12, shortly after ten o’clock in the evening in Florida. At that point, Bush’s lead had dropped to about 150 votes.

BAKER: I had my inside group in the office with me, and we read through [the ruling] rather quickly. It didn’t take us long to conclude that the election was over. I called the governor and said to him, “Congratulations, Mr. President-elect.” But we didn’t want him to make any statement claiming victory because we wanted Gore to have time to come to his own conclusion. He did so, and the next night he gave a truly wonderful concession speech. That was not easy for him, I know.

EVANS: Reporters were running out of the Supreme Court trying to figure out what it says at the same time that we were trying to figure out what it says. There was early talk that Gore thought he had this opening or that opening, but before I went to bed that night, I knew that we had won.

ALLBAUGH: I walked into Jim Baker’s office, and he had just talked to the president-elect. He said, “Joe, do you want to go home?” And I said, “Yessir, I’ll make it happen.”

BAKER: People keep misinterpreting the decision in Bush v. Gore. They keep calling it a five-to-four political decision. But the ruling was seven to two, on constitutionality, with one justice appointed by a Democrat voting with the majority and another appointed by a Republican voting with the minority. The high court held that the Florida Supreme Court’s recount was unconstitutional because the lack of uniform counting rules violated the equal-protection clause of the U.S. Constitution. The five-to-four decision that came down at the same time was with respect to remedy. It simply said there wasn’t time to finish a statewide recount.

EVANS: I remember calling my son, who was ten years old at the time. We had hunted together every fall, and we were going to go after the election, but that got blown up, of course. I called him and said, “Donnie, your godfather is going to be the president of the United States.” And he said, “Does that mean we get to go hunting this weekend?”

OXFORD: I flew back to Houston. By this time my law partners—not to mention my clients—were wondering where the hell I was. So I just went home and got back to work. We were worn out, and it didn’t feel like much of a victory yet.

FLETCHER: When the decision came out that night, I did what I always did: I showed my copy to a lawyer and said, “Tell me what it says in English.” You got to a point where you became numb to it. One day there would be a great court case, and the next day there would be a bad one. We had been trained not to get too up or too down. But then I came into the office the next morning, and Joe said, “My plane is leaving in an hour. Do you want to be on it?” So I ran back to the hotel, threw my stuff in a bag, and got on the plane. I kissed the ground when we landed in Austin.

ALLBAUGH: That night we orchestrated giving the acceptance speech in the Texas State House of Representatives, and Democratic speaker Pete Laney introduced the president-elect to the country. But the night was a blur. I was so tired. I’m not sure I could carry on a conversation.

BRANCH: I’ve heard the story from Pete Laney that when they went out, the president-elect commented to him, “Don’t mess it up.”

BARTLETT: It was an extraordinary moment to hear the speech at the Capitol, where a lot of us had spent time with him when he was governor. It reminded me that things had come full circle. Afterward my wife and I and some friends went to the Brown Bar—we were supposed to go the night of the real election. But we never felt like there was a proper celebration.

MCKINNON: The thing about campaigns is, there is no greater experience than winning, and there’s no worse feeling than losing. It is so bad that I almost quit doing them for a while. You invest so much time and energy that it is just crushing to lose. And sometimes it’s crushing to win. In 2000 we never really got to celebrate. There was a mental and physical letdown even after we had won. I was sick after that campaign.

DOWD: There wasn’t a break after it ended. In the time between Bush’s being declared the winner and the inauguration, I wrote the first memo looking ahead to the 2004 election.

“ ‘What’s Happening in Your Country?’ ”

In the end, Bush’s 537-vote victory in Florida decided the 2000 election, but the question still lingered: Who really won? In 2001 two independent media investigations, one led by the Miami Herald and USA Today and the other sponsored by outlets such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Associated Press, concluded that had the counting continued, Bush most likely would have defeated Gore.

DOWD: I’m sure there are some people in the Democratic party who still believe it was a stolen election. But I think the public has moved past it. They’re more pissed now at things that have been screwed up on other levels.

BAKER: People ask me if we’ll litigate every close election now, but I don’t believe that will happen. We were fighting to preserve an election in Florida. I used to get calls from former foreign ministers and prime ministers that I worked with as Secretary of State, and they would say, “What’s happening in your country? Can’t you get an election right?” And I would say, “I’ll tell you what’s happening: Our system is working. I dare say that if something as tension-filled and emotional as this were occurring in your country, you’d see tanks in the streets.” Some had to acknowledge that that was true.

BARTLETT: It was the unspoken aspect of arriving in Washington after the election was resolved: “Is this going to be an anticlimactic presidency because of the way we won? Can we overcome the way we came in?” That had to be in the back of everyone’s mind; I know it was in mine. Little did I know what was waiting.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- George W. Bush

- Dan Branch