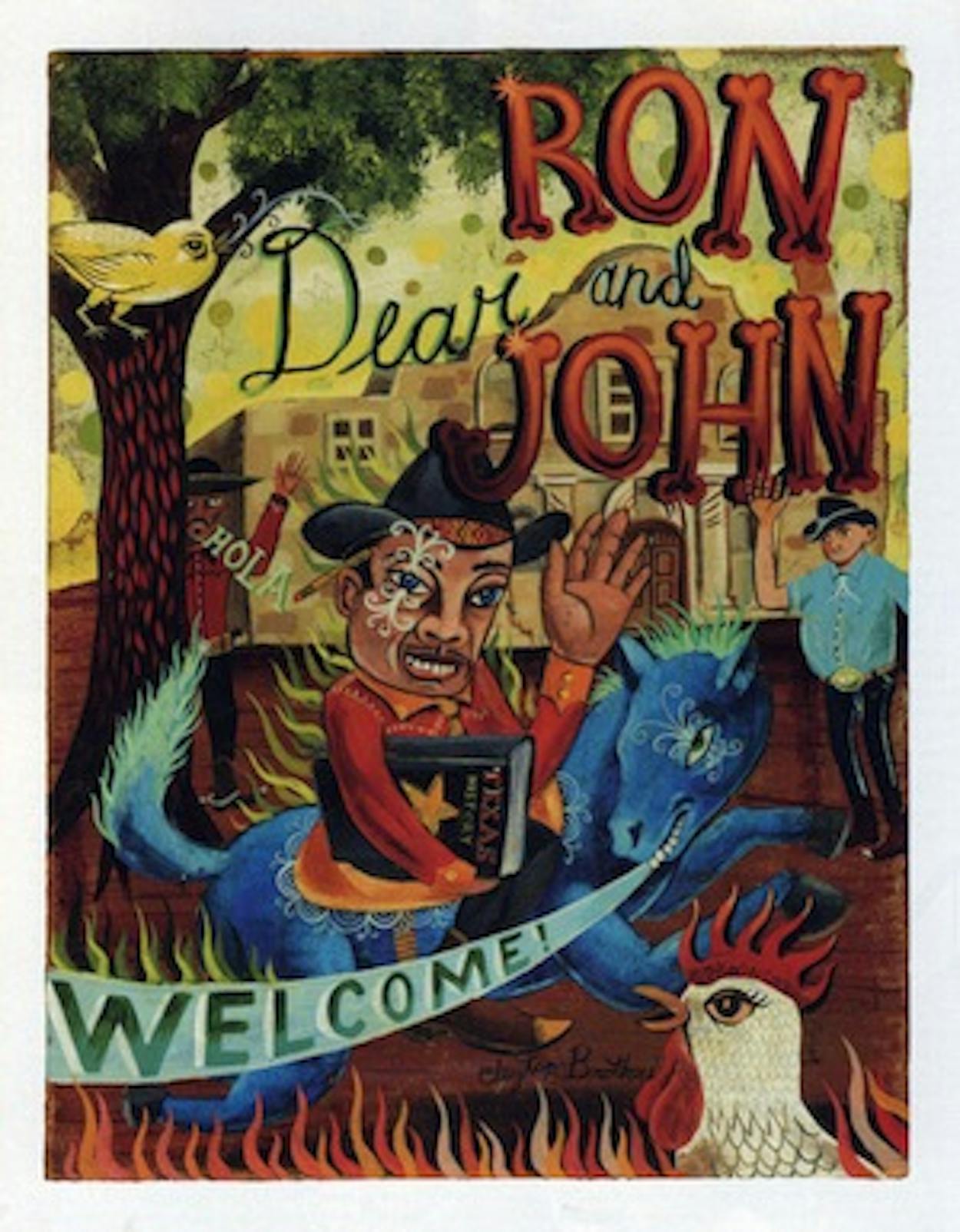

Dear Ron and John:

Heard y’all are coming to Texas to make a moving picture. We are mighty excited! It has been a long, lonely fifteen years since somebody made an epic about our favorite subject, the Alamo. Here are a few tips to make your stay productive and enjoyable.

Tip Number 1: FINDING THE ALAMO

ALTHOUGH YOU’LL BE STAYING in Austin, you’ll want to visit the Alamo City to do research, but once in San Antonio, stay calm. Everything down there is Alamo this and Alamo that. If you’re trying to look up the Alamo in the telephone book, be forewarned: There are four pages of “Alamo” listings, including Alamo Dog and Cat Hospital, Alamo Investigation Agency, Alamo Funeral Company, and so on. The one you want is Alamo: Shrine of Texas Liberty, 300 Alamo Plaza. The best way to find the Alamo Plaza Alamo is to check in at the historic Menger Hotel (Kinky Friedman schlepped here). Get a room on the north side and look out the window. That little yellow-stone, mission-style number—it’ll be all lit up at night—is the ticket.

Never divulge directly to the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, who are in charge of the Alamo, that you are making a movie about it. It will be their patriotic duty to call the police and make wretched all the days of your lives. The only emotion officially sanctioned by the DRT is awe. P.S. The facilities are out back—they get irritated if you ask.

Since a tour of the Alamo takes no more than half an hour, tops, plan on taking a long lunch break to sort through your impressions. There are plenty of restaurants where you can dine alfresco along the River Walk, a short distance away and easy to find. (Just follow the 4,742 signs that say “River Walk.”) By the way, do not confuse this river with the one in John Wayne’s epic, the Río Bravo (Rio Grande), which is 150 miles from here. What you are looking at and dining beside is the San Antonio River.

Historical note: Santa Anna’s army used neither paddleboats nor motorized barges to cross the river, nor was there a really good fajita place located on it at that time. Mexican-food advice is always important to outlanders, so listen up. Expensive Mexican restaurants are what we call oxymorons, so don’t plan on spending much for Tex-Mex. It should be cheap and it should come in two colors: brown and yellow.

Tip Number 2: LOOKING AT THE BIG PICTURE

WE SAW THE NEWS RELEASE about how the big guy at Disney, Michael Eisner, in post-9-11 mode, put the project on the fast track. Ron, we read in the New York Daily Newshow you want to “capture the post-Sept. 11 surge in patriotism.” And we heard about the efforts of your producer, Brian Grazer, to steer the film away from anything controversial, announcing that it wouldn’t ally itself with Mexicans or Texians. Don’t you see that it has to, Ron? If it’s about patriotism, then it’s about love of country. There were two opposing forces at the Alamo: One was Mexican, one was Texian, and they didn’t like each other very much. The Mexican leader, General Antonio López de Santa Anna, considered the Texians “pirates,” and the Texians considered the Mexicans deluded followers of a corrupt and tyrannical government. Ron, we know you know how to wax patriotic. We’ve seen all the episodes of The Andy Griffith Show; we’ve seen Apollo 13. So we know you have it in you. John, we’re not so sure about you. Texans have a long memory, and those of us who saw Lone Star remember how you had the heroine say, ringingly, “Forget the Alamo.” And some of us, like me, remember an earlier offense, in Piranha, when you placed piranhas in the San Marcos River. That was okay; it was a spoof of horror flicks. But we’re in shrine country now, John, and you need to pay attention to what you write. Every Alamo movie since the days of the silents has claimed to be authentic, and every one of them has played fast and loose with the facts. So watch it.

One thing that needs to be understood from the get-go is that anything—anything—done or said about the Alamo can create controversy in Texas. For example, the descendants of both Mexicans and Tejanos (Mexicans born in Texas) always complain about how their forebears are misrepresented in Alamo films. Back in 1915 the racism of The Martyrs of the Alamo led Mexican Americans in South Texas to boycott the film. Anglos get mad too. The Daughters of the Republic of Texas pitched a fit when Viva Max! (1969) mocked some of the solemnities surrounding the Alamo legend. Even when a filmmaker tries his best to be fair, as John Wayne did with The Alamo (1960), there can be trouble. Jesus Trevino, for example, who directed the revisionist Alamo docudrama Seguin (1982), accused Wayne of picturing Mexicans as “either bandidos, dancing señoritas, sleeping drunks, or fiery temptresses.” More recently, other groups have protested naming public schools after Travis (because he championed slavery and abandoned his wife and child) or Bowie (because he was a slave smuggler). In a politically correct age, the heroes of the Alamo are apt to come off as a bit unsavory.

As you will soon discover, nobody knows exactly what the hell happened at the Alamo. All we know for sure is that the Texians lost and the Mexicans won on March 6, 1836. But as any red-blooded Texan will be happy to tell you, Texas soon came out ahead because Santa Anna’s army was defeated some six weeks later, on April 21, at San Jacinto. Since then, politicians, historians, and moviemakers have touted the Alamo as a moral victory.

Tip Number 3: TELLING THE TRUTH

IF YOU WANT TO MAKE a powerful film, then you are going to have to get down to historical cases. This means you will have to figure out how to deal with four major figures: the trinity of Alamo heroes—Davy Crockett, William B. Travis, and Jim Bowie—and the head honcho of the Mexican Army, Santa Anna. Unfortunately for you, each of them resides uneasily in the half-light of the known and unknown.

For example, how did Davy Crockett die? Quien sabe. Did he go down fighting or did he surrender only to be summarily executed? How Davy died is a Very Big Deal in Texas, and if you decide that he surrendered, a whole bunch of Texans will hate you for it. Collateral Davy problem: Did he wear a coonskin cap? You cannot imagine how much ink has been spilled on the issue of Davy’s headgear. What he did not wear was a conventional cowboy hat (á la Brian Keith in 1987’s The Alamo: Thirteen Days to Glory). He probably did wear a coonskin cap (á la Fess Parker in Disney’s 1955 Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier). Go for it.

Did Colonel William B. Travis draw a line in the dirt? Again, who’s to say? Although it makes for stirring cinema, the Duke didn’t use the gimmick in his epic. Collateral question: If Travis did draw a line in the dirt, did a man named Moses Rose decline his attractive offer to die for Texas and skip out instead, thus becoming the Yellow Rose of Texas, as Peter Ustinov quipped when he was in San Antonio making Viva Max!? You decide.

How old was Travis? Usually cast as an older man, like Laurence Harvey’s popinjay in Wayne’s world, Travis was actually a hot-blooded 26-year-old who fled to Texas because if he had stayed in Alabama, he would have been thrown into debtor’s prison. He knew some Latin—he was perhaps the best educated of the Alamo defenders—and may have suffered from a venereal disease. In his diary he made the entry “venerao mala,” the exact meaning of which historians wrangle over to this day. Does it mean “venereal [disease] bad” or “food poisoning” (veneno malo), or is the reference to Venus, indicating that his love life at the time was not good? We just don’t know.

What we do know is that Travis did indeed write his stirring patriotic letter—”I shall never surrender or retreat”—the most powerful, authenticated moment in the Alamo saga. You could show him writing it while someone reads it aloud (voice-over?). That way, John, you don’t have to pen any long speeches explaining everything. Incidentally, in 1999 then-governor George W. Bush used Travis’ letter to inspire the U.S. Ryder Cup golf team the night before their great come-from-behind victory, so it still works.

As for Bowie, how sick was he? Although reports vary wildly, most evidence suggests that he was quite ill with a lung infection, which leads to the more important dramatic question, How did he die? One thing is sure: If you follow a contemporaneous account published in El Mosquito Mexicano, a Mexico City newspaper, you are going to run into serious trouble with Texans. According to a letter printed on April 5, 1836, “the perverse and boastful James Bowie died like a woman, almost hidden by covers.” Texans’ preferred version, for which there is no credible source, is that Bowie died in his bed surrounded by dead Mexican soldiers that he had heroically slain.

Santa Anna is going to be a tough customer for a lefty like you, John. He once stated, “A despotism is the proper government for [the people of Mexico].” Texas, of course, was part of Mexico, ergo . . . He specialized in self-promotion and fought for every side there was in Mexico at one time or another. In May 1835 he scored a brilliant victory over rebels in Zacatecas and let his troops rape, kill, and pillage for two riotous days. He was fond of executing prisoners. He called himself the Napoleon of the West. Early on the morning of March 6, before the Alamo fell, Santa Anna ordered his bugler to play the degüello, a piercing melody signaling that no quarter would be given.

Which brings us to another difficult question: What kind of music did the Alamo defenders listen to? This will be a major issue. Epics have to have music, and Dmitri Tiomkin is no longer around to hide behind. Past examples may be instructive. In 1937’s Heroes of the Alamo, the beleaguered Texians sing “The Yellow Rose of Texas,” although the song wasn’t actually written until 22 years after the battle, in 1858. In The Alamo, heartthrob Frankie Avalon was brought in to attract the youth audience, and the treacle he crooned, “The Green Leaves of Summer,” copped an Academy-award nomination for best song.

A bold thing to do would be to sign up rocker Ozzy Osbourne for the soundtrack. Famous for his onstage antics (eating live bats, and the like), OO took a whiz on the Alamo cenotaph on February 19, 1982, and was promptly arrested. Banned from appearing in the Alamo City thereafter, he bought his way back in with a $10,000 contribution to the DRT. Or you can always go the safe route by lining up Jennifer Lopez for Santa Anna’s army and Britney Spears for the Texians. The demographics are obvious, and it could go platinum.

The solution to these and all other historical quandaries: Make it up. Everyone else has.

Tip Number 4: BRINGING IT HOME

NO ONE HAS EVER MADE a good Alamo movie, but that’s no reason to surrender. Frankly, though, I’m a little worried about something Brian Grazer said about the Alamo in a statement widely quoted in the press: “It’s not about patriotism so much as about individuals who take a stand. It’s about how Americans struggled to survive. You could say it reminds us of who we are.” The tendency toward vague allegorizing should be avoided at all costs. With that in mind, here are some surefire pointers for grounding the story in real history.

Hemingway once advised Dos Passos about a novel-in-progress to put some weather in his “goddamned book.” This is never a bad idea. During the thirteen days of the siege, from February 23 to March 6, 1836, temperatures averaged in the high thirties and low forties, enough to make everybody pretty miserable. Also, South Texas in late winter looks like unvarnished hell, so the scenery should be bleak.

Make your Alamo part of a community; don’t stick it out in the middle of nowhere. The Alamo, as you will discover on your visit, was at the center of a town. Make it come alive with a lot of mise-en-scène stuff, even mariachi singers and tamale vendors if you can’t think of anything else.

Get the ethnicity of the population right. These days we are very touchy. The defenders included at least seven Tejanos and men from twenty states and six countries. Among the civilians inside the garrison were women and children and African Americans. Memo to John: There were no black Seminoles at the Alamo.

Finally, my absolutely last piece of advice, I promise: Give the defenders a background, a context. Show why they came to Texas in the first place. Were they on the dodge from the law? Some were. Some came because of family problems, some because they wanted to get rich quick, but nobody came because he wanted to hole up in a run-down old mission and wait for thirteen days to be butchered by Santa Anna’s troops.

I’m glad we had this little talk. When you get to town, let’s do lunch.