The chuck wagon is the most instantly recognizable symbol of the American West. Its silhouette, with its billowing canvas top and its fly stretched out over its drop-down table, epitomizes down-to-earth cooking, the hospitality of the open range, and the hearty companionship of cowboy life. Today no Western event is complete without a chuck wagon breakfast, and chuck wagons provide meals at weddings, calf ropings, farm auctions, church camps, state fairs, business conventions, and White House functions. There is an American Chuck Wagon Association, which last year sponsored more than forty chuck wagon cook-offs in thirteen states. You can listen to the music of the Chuck Wagon Gang while driving to one and eat at a restaurant called the Chuck Wagon on the way back.

The chuck wagon is a nineteenth-century Texas invention, a product of the expanding ranching industry after the Civil War. It was a rolling kitchen, pantry, and storeroom, capable of feeding a dozen working cowboys three meals a day. Its distinguishing feature was the chuck box, a tall cabinet in the rear of the wagon whose door, hinged at the bottom, dropped down to make a table supported by a single leg. The box’s interior was an arrangement of drawers, shelves, and compartments that held groceries, cooking equipment, tin cups and plates, and utensils. A coffee mill and a rack for butcher knives were often affixed to the outside of the chuck box. On many wagons, a compartment called a boot hung below the chuck box to hold Dutch ovens and skillets, and a cow hide called a coonie (from the Spanish cuña, for “cradle”) was slung between the axles and carried kindling or cow-chip fuel. A 35-gallon cask might be mounted on the side of the wagon to provide drinking water. The bed of the wagon held enough bulk provisions to feed twelve or so men for a month—bacon, salt pork, beans, rice, coffee, flour, dried fruit, sugar, molasses, lard, and canned goods—as well as horseshoes, branding irons, and a stack of bedrolls.

The chuck wagon was the responsibility of the cook, who had few duties other than to keep the cowboys fed. He prepared his meals by digging a trench and burning wood in it until it was full of coals; he then placed the pots and skillets on the coals. A good camp cook could get a meal for the cowboys ready in about an hour once the fire was started. At big roundups, cooks sometimes found their supplies stretched thin by the number of cowboys involved; one cook on the Miller 101 Ranch, in Oklahoma, solved the problem by placing the pots on the opposite side of the fire trench from the chow line, strictly limiting the amount of time a hungry cowboy could hold out his plate to be filled.

Chuck wagon cooking has been romanticized by latter-day enthusiasts, but the reality was probably closer to the meals described by Evan Grey “Parson” Barnard, who cooked for the Half Diamond R, in Oklahoma Territory, in the 1880’s. “Breakfast: sour-dough biscuits, white gravy, sowbelly, and black coffee; dinner: sowbelly, black coffee, sour-dough biscuits, and white gravy; supper: black coffee, sowbelly, white gravy, and sour-dough biscuits.”

Chuck wagons were necessitated by the long cattle drives that moved millions of cattle out of Texas to railheads in Kansas and ranges in Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana in the quarter century after the Civil War, and by the immense roundups that gathered the cattle for these drives. Before the war, cowboys working smaller herds of cattle might carry a few days’ worth of provisions in their saddlebags, or, for longer absences, load groceries and cooking equipment on pack mules or horses, or even utilize a two-wheeled ox- or mule-drawn cart resembling a Mexican carreta to carry supplies. Drives lasting two or three months and roundups covering vast distances required something more elaborate.

Charles Goodnight solved the problem by inventing the chuck wagon. In the spring of 1866 Goodnight and his partner, Oliver Loving, were planning to drive two thousand head of cattle from Palo Pinto County to Fort Sumner, New Mexico, where the Army was buying beef to feed the eight thousand Navajo it had imprisoned there. The drive would require eighteen men and would cover six hundred miles. Goodnight, who had once worked as a freighter, bought a surplus Army wagon and had it reconfigured, adding iron axles and bois d’arc running gear. A carpenter from nearby Parker County built a chuck box to Goodnight’s specifications, and Goodnight bolted it to the bed of the wagon, creating the world’s first chuck wagon. Decades later Goodnight told his biographer, J. Evetts Haley, “It has been altered little to this day.” The wagon was so heavy it took a team of oxen to pull it.

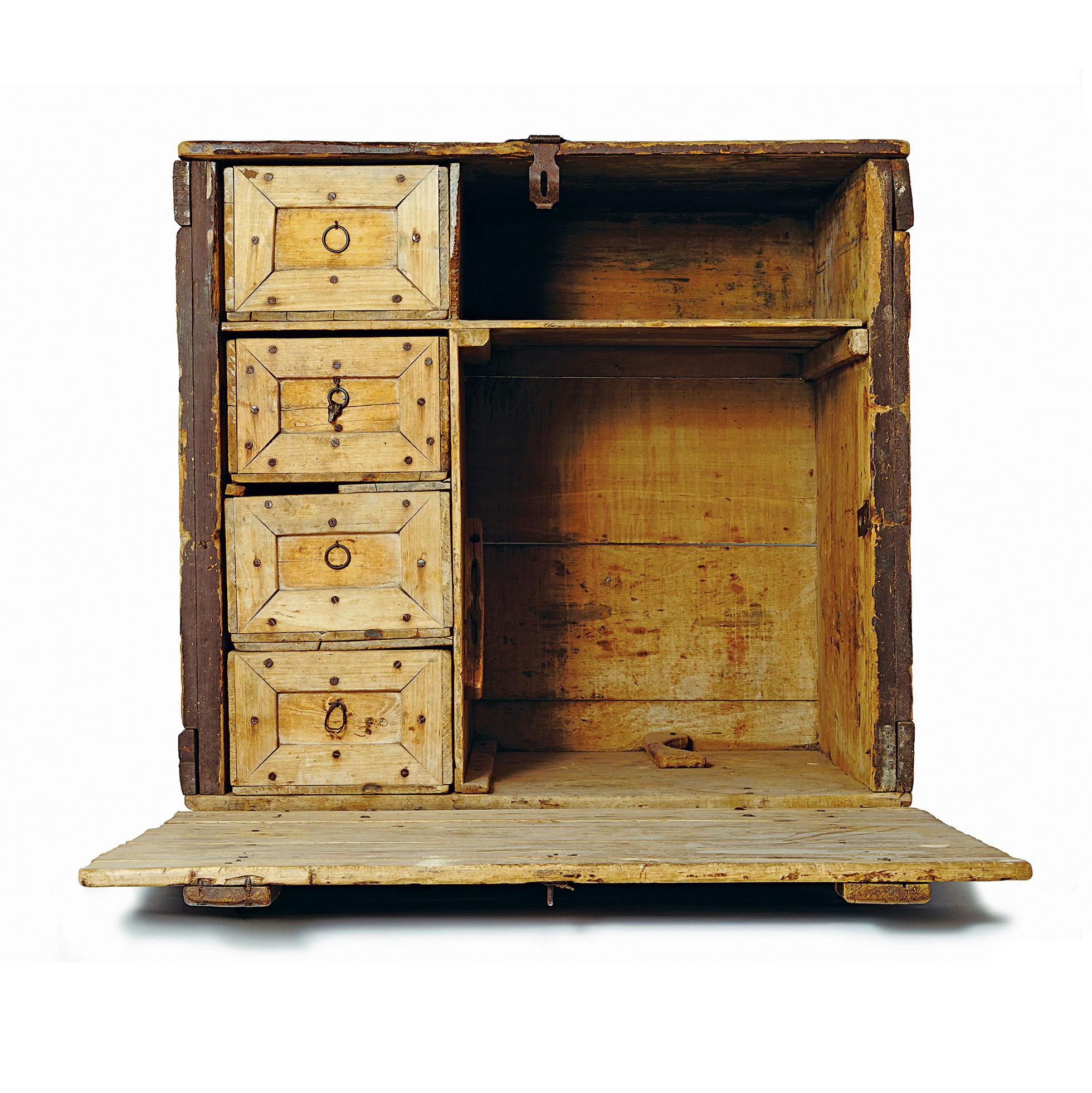

Goodnight’s chuck box can be seen today at the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum, in Canyon. It is about three feet high and three feet wide, made of pine boards nailed and screwed together, with a door hinged at the bottom that drops down to make the work table. Inside are a shelf and four deep drawers, one of which has dividers made from a Heinz ketchup crate. Three of the drawer pulls are harness rings; the fourth is a knotted strip of rawhide.

Byron Price, the director of the Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West, at the University of Oklahoma, thinks that Goodnight’s chuck box may have been inspired by the portable drop-front writing desks of the period or by the compartmentalized mess chests that mid-nineteenth-century travelers carried on long journeys. Goodnight was a close observer and an original thinker, and no matter what his inspiration, he gave the West an ineradicable legacy.

Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum, 2503 Fourth Ave, Canyon (806-651-2244). Open Mon–Sat 9–6 from Jun to Aug; Tue–Sat 9–5 from Sep to May.