Empire of Cotton: A Global History (Alfred A. Knopf), by Harvard professor Sven Beckert, is cut from the same cloth as last year’s surprise publishing sensation, French economist Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-first Century. Both books are groundbreaking economic histories that convincingly demonstrate how capitalism’s “invisible hand” has too often meant the back of the hand for countless workers and, more recently, an endangered middle class. But of the two books, Empire of Cotton should hit Texas readers much closer to home; all our familiar tales of cattle kingdoms and oil barons notwithstanding, cotton ruled the culture and economy of our state for its entire first century. And although we have since created a defiantly independent “we built this” self-image, in Beckert’s wide-angle perspective Texas stands neither alone nor very tall. For much of our storied past, we were mere slaves and serfs in the global empire of cotton—and well into the twentieth century remained desperately poor because of it. The story of cotton in Texas is one of profits and prosperity that largely went elsewhere, leaving us a legacy of shame and poverty that to this day haunts our collective psyche and plagues our public policy.

Beckert’s ambitious thesis, that cotton rather than steam or steel built globalized industrial capitalism and “ushered in the modern world,” begins with a millennia-old cottage industry that once extended from “the banks of the Upper Volta to the Rio Grande, from the valleys of Nubia to the plains of Yucatán.” Making cotton cloth remained a piecework process until the mid-eighteenth century, when a succession of British inventions—the flying shuttle, the spinning jenny and spinning mule, and eventually water- and steam-powered looms—transformed northwest England into the booming cradle of the Industrial Revolution. By 1830 cotton manufacturing accounted for one in six British workers, and “white gold” had created a “world economy in which rapid growth and ceaseless reinvention of production became the norm . . . a world in which revolution itself would become a permanent feature of life.”

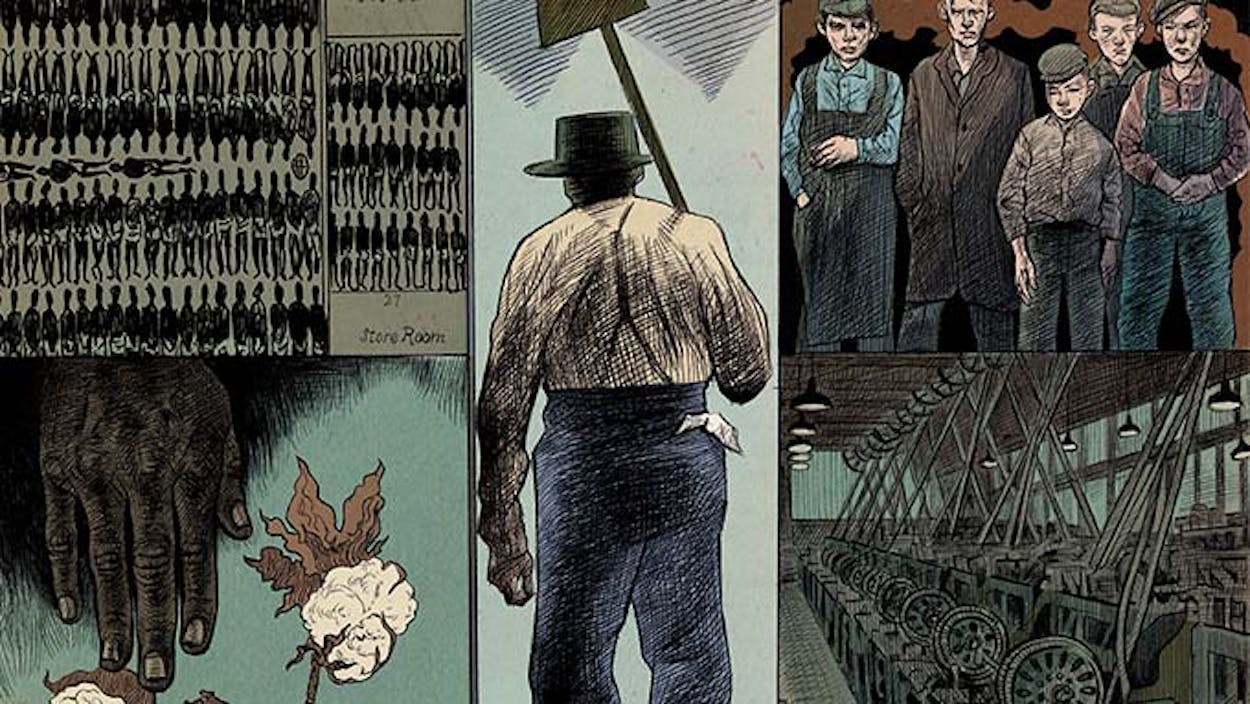

The dystopian future so often conjured in today’s popular culture pales next to the infant Industrial Revolution’s scrapbook of actual horrors. England’s “dark Satanic mills” (poet William Blake’s 1804 characterization) could meet their unremitting demand for labor only “by recruiting the weakest members of society first,” according to Beckert. Women and children became the charter members of the industrial proletariat; a typical ten-year-old worker, already a two-year veteran of a Manchester spinning mill, testified in 1833 that her workday ran from five-thirty in the morning until eight in the evening. She was routinely beaten with a strap and, if she was late to work, forced to pace the factory floor with an iron weight hung around her neck—yet under English law she could be imprisoned at hard labor if she walked off the job.

The English mills—and, increasingly, those of New England—had a similarly predatory appetite for cheap raw cotton, a need met by plantation slavery, already established in the New World by sugar and tobacco growers. But cotton cultivation quickly exhausts the soil, and only the southern United States provided a sufficiently abundant supply of cheap land and forced labor to meet the burgeoning demand. As soils became depleted, this southern “commodity frontier” marched west. We like to imagine that frontier Texas was the domain of freedom-loving Davy Crocketts, but it was the invisible—at least to most Texas historians—hand of European and New England capital that pushed many of these settlers into our cotton-friendly coastal plain, with slaves collateralizing the loans on pricey plantation start-ups.

“All the way to the Civil War,” Beckert writes, “cotton and slavery would expand in lockstep, as Great Britain and the United States had become the twin hubs of the emerging empire of cotton.” By 1860 raw cotton accounted for 60 percent of all U.S. exports, while manufactured yarn and cloth accounted for nearly half of Britain’s, with most of its raw cotton coming from America. A South Carolina senator’s declaration that “England would topple headlong and carry the whole civilized world with her” if slavery was abolished in the U.S. didn’t reflect Southern hubris so much as the presumption, widely held throughout the “civilized” world, that cotton could never be grown in industrial quantities by wage labor.

King cotton’s dependence on slavery made the American Civil War every bit as much an existential crisis for fledgling global capitalism as it was for a young nation. Beckert repeatedly stresses that the invention of big government—powerful nation-states that could create a globe-encircling transportation infrastructure, police it, and guarantee the integrity of its markets—was as important to the rise of capitalism as new machines. And when the Civil War removed most American cotton from the market, the capitalists desperately turned to this global network and the governments that had created it. From India to Egypt to Brazil, bureaucrats and administrators created new sources of raw cotton with a nimbleness that astonished marketplace veterans. By the end of the war, Beckert writes, “the cotton capitalists had learned that the lucrative global trade networks they had spun could only be protected and maintained by unprecedented state activism.”

The defeated American South also had to quickly adapt to this new world. Sharecropping, which allowed freed slaves some degree of autonomy but ultimately chained them to their landlords and creditors, became the new cheap-labor solution. And the lot of freed blacks continued to worsen as ex-Confederate “redeemer” legislators passed laws that stripped African Americans of their newly won political franchise and legal rights, while separate, woefully inadequate public schools ensured that succeeding generations would remain bound to the land. Dispossessed white farmers also swelled the ranks of sharecroppers, but unlike their black counterparts, late-nineteenth-century Populism gave them some brief political traction.

Onerous human costs notwithstanding, the sharecropped South produced cotton as never before, with Texas now leading the way. The federal government swept Native Americans from Texas’s commodity frontier, and by the 1880’s inland Dallas had become an important cotton-trading hub, staffed by representatives of the world’s largest agribusinesses. By 1920 our raw cotton production had spread all the way to the irrigated plains of far West Texas and was ten times what it had been in 1860. Yet the technology of cotton farming remained essentially unchanged from the antebellum era, requiring the same dawn-to-dusk hoeing, weeding, and handpicking.

Texas’s labor-intensive cotton crop, prodigious as it was, merely earned our membership in what Beckert refers to as the “global countryside”—a downscale club that consisted principally of the European powers’ sprawling, exploited colonial empires. Across five continents, peasants and sharecroppers produced massive amounts of cotton. “Thanks to their backbreaking and ill-remunerated labor, well into the twentieth century trade in cotton and cotton goods ‘was still by far the largest single trade’ in both the Atlantic world and Asia,” Beckert writes.

For sharecroppers and mill workers throughout the world, this bounty became a poverty-sowing bust, as prices fell and, in what today has become an all-too-familiar dynamic, capital hopscotched around the globe, searching for new sources of ever cheaper labor and yet-to-be-exploited land and markets. Beckert’s vast canvas doesn’t allow him to detail the consequences of cotton capitalism in Texas, but the troubles he cites in general were certainly endemic here. In 1930, the year that oil finally replaced cotton as the driver of the Texas economy, the state’s per capita income was a third lower than the national average. Our 65 years in the postbellum global countryside had left Texans with a sense, much remarked upon at the time, that we were little more than victims of Eastern Seaboard economic colonialism, even as our state’s leaders and thinkers attempted to fashion an entirely new, often ahistorical image. Cultural landmarks like Walter Prescott Webb’s The Great Plains (1931) and the 1936 Texas Centennial helped reinvent Texas as a heroic Southwestern cattle culture rather than a defeated Southern cotton culture, largely disregarding cotton’s centuries-spanning tenure as the state’s cash cow.

Even now, Texas continues to produce America’s biggest cotton crop, though as Beckert notes, American cotton is “so uncompetitive on the world market that [cotton growers] receive enormous federal subsidies to continue to farm it.” The much-diminished importance of cotton relative to our state GDP is far exceeded by the ongoing if often sublimated influence of cotton on Texas’s state of mind. Our peculiar psychological amalgam of cultural insecurity and outsized braggadocio stems directly from our long servitude to the “lords of the loom”—the out-of-state cotton manufacturers who profited on the backs of Texas farmers—and our subsequent campaign to recast ourselves as a unique, fiercely self-reliant people. Yet Beckert’s global narrative dramatically deflates this overblown myth of Texas’s uniqueness, which among today’s Texas politicians has metastasized into a giddy exceptionalism. During our first century, Texas was at best a winner among the global countryside’s commodity-producing losers, a vassal state whose overworked and underpaid population remained subject to the vagaries of cotton prices and the manipulations of outside, often overseas, capital.

Despite 85 years of an increasingly diversified and powerful Texas economy, cotton is not likely to soon be bred out of our state’s cultural and political DNA. We still run things under Texas’s 1876 redeemer constitution, and our current leadership’s disregard for the working poor and their children’s educational opportunities is a page right out of cotton capitalism’s worker-as-disposable-commodity playbook. When onetime cotton farmer (and former recipient of the lavish federal cotton subsidy) Rick Perry runs for president again, he’ll boast of an economy that excels in creating low-paying jobs, even as it continues to lag behind competitors like resurgent California in high-end economic indicators such as venture capital, patents, and university research centers (the same R&D cutting edge that Perry tried to dull at Texas universities when he was governor). But Perry’s populist anti-intellectualism was already old hat in Texas back when Lyndon Johnson was feuding with John Kennedy’s “Harvards,” its origins dating to our resentment of the better-educated, better-capitalized lords of the loom.

Nevertheless, Perry now wears glasses to appear more intellectual, and public sentiment in today’s Texas is similarly conflicted. Our deeply conservative, libertarian body politic combines a near-religious reverence for free markets with an increasing vitriol against the very institutions—big banks, big government, Wall Street, corporate welfare—that built global capitalism into an invincible, socialism-crushing juggernaut. Indeed, this new economic populism spans the political spectrum from far right to far left, giving rise to the hope that concludes Beckert’s sweeping economic saga, “that our unprecedented domination over nature will allow us also the wisdom, the power, and the strength to create a society that serves the needs of all the world’s people—an empire of cotton that is not only productive, but also just.”