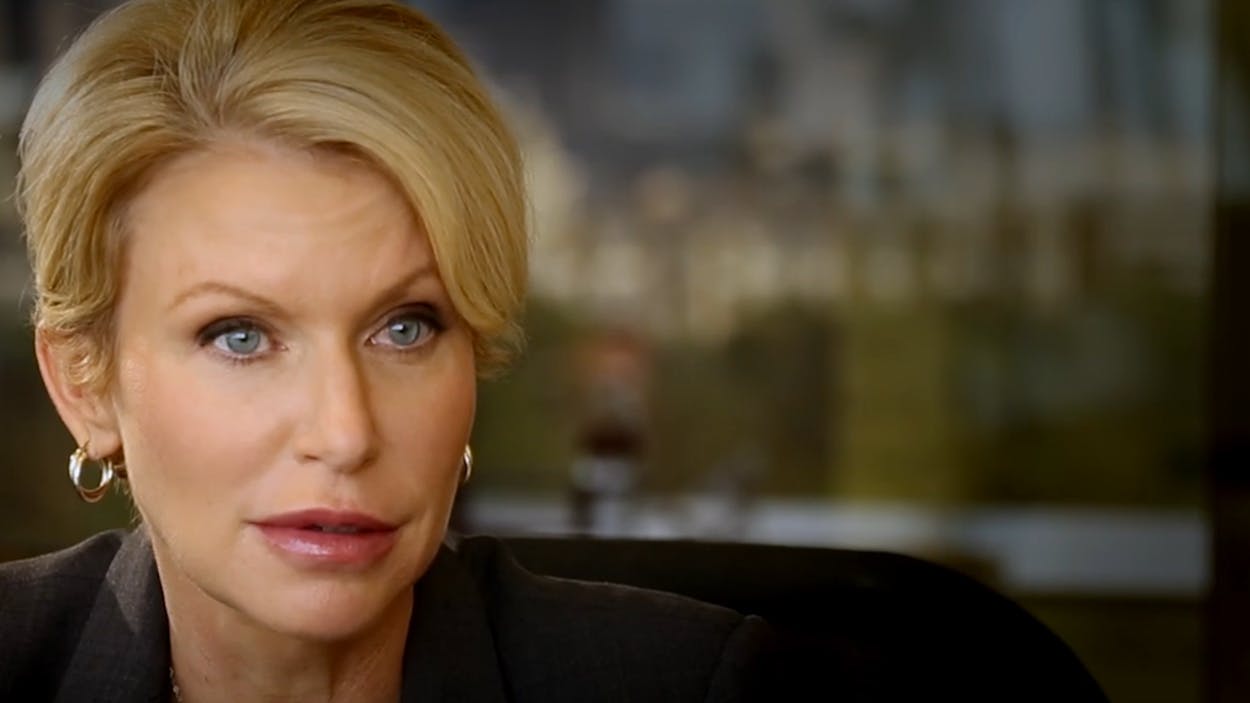

Susan Hawk’s tenure as Dallas County District Attorney came to an end this week. It was an unusual twenty months in the office—it started almost immediately with controversy, led to revelations that the prosecutor had sought mental health treatment, and included surprising firings and improprieties regarding financial matters. But as of this week, Hawk is done serving.

“It is with a heavy heart that I must tender my resignation as Dallas County District Attorney,” she wrote to Republican Gov. Greg Abbott, who will appoint her replacement.

“It’s been an honor and a privilege to serve this office and the citizens of Dallas County alongside you, but my health needs my undivided attention. More than my words could express, I appreciate the grace I’ve been shown as I’ve tried to balance my health and my duties. This has been a very difficult decision for me. “

There was a lot of discussion of mental health as it pertained to Hawk and her time as a public official. That’s a conversation that’s difficult to have culturally, and an especially difficult one to fit into the narrow world of partisan Texas politics. Hawk, a Republican serving in a county that tends to overwhelmingly elect Democrats, was at times criticized fairly, but her mental health was also used as a springboard for critique.

After it was revealed that Hawk was seeking treatment for depression, the Dallas Observer questioned whether or not she was a “full-on lunatic.” Hawk’s former administrative chief, whom the former DA fired, filed a petition to have her removed from office, citing “Hawk’s use of prescription drugs, her recent treatment for major depression and her ‘paranoid delusions’” among the reasons that she should be considered unfit for office.” The Dallas Morning News described her “breaks with reality,” quoting anonymous sources who said they “don’t know who she is anymore.”

Meanwhile, Hawk’s allies voiced the need to reduce stigma around mental health care and mental illness. A GOP official, speaking anonymously to the Morning News, asked, “If she had cancer, would people be calling on her to resign?”

Mental illness tends to be used as a cudgel against public figures, especially politicians. When a political opponent discusses their own mental health struggles, they lack “backbone”; a political opponent’s mental health can be floated as a sign of “dishonor.” (This came up during the 2014 statewide elections, when Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick’s history of seeking treatment was brought up during his primary race against David Dewhurst.)

Susan Hawk faced a lot of challenges not just in terms of holding office while seeking treatment, but in terms of how people would judge her for doing both. Mental illness happens, and it doesn’t indicate a moral failing on the part of the person dealing with it. We’d benefit as a society, generally, if that understanding were more deeply embedded into how we treat people who live with or require treatment for mental health troubles. Hawk’s experience in the criminal justice system revealed this at times during her career, especially when she served as a judge. As Skip Hollandsworth wrote in Texas Monthly last fall:

A few years into her tenure [as judge of the 291st Criminal District Court], Hawk started a program that was designed to help defendants who had been diagnosed with mental disorders. Instead of sending them to the penitentiary, where she knew their conditions would only worsen, she offered those who had committed non-violent crimes an opportunity to receive mental health services. She required those offenders to come to her court every Thursday so that she could make sure they were staying on their medications and attending their therapy sessions.

That’s the sort of insight into mental health that the criminal justice system—and the culture at large—could benefit from. Of course, Hawk won’t get the opportunity to bring that understanding to her position as DA now that she’s resigned, and it seems that many in criminal justice lack that comprehension. When Hollandsworth asked Hawk’s colleagues from her time as a judge if they thought her own history of mental illness might have informed her approach to offenders with similar challenges, they revealed the same sort of glib misunderstanding of mental illness as “erratic” behavior from lunatics.

I asked people who knew Hawk in those years if it was possible the reason that she was so compassionate toward mentally ill offenders was because she was privately struggling at the time with her own issues. They replied that they had never considered such a scenario because they had never seen Hawk act erratically. “Listen, this courthouse is teeming with a bunch of half-crazy lawyers,” one high-profile attorney told me. “Compared to those people, Susan came across as a saint.”