It was on Monday morning, March 16, 2015, when the rumor started racing down the hallways of the Frank Crowley Courts Building, in Dallas. Over the weekend, Susan Hawk, the new district attorney of Dallas County, supposedly had met with her first assistant, Bill Wirskye, and accused him of breaking into her house in hope of finding a compromising photo that had been taken of her years ago when she had been at a bar with a group of her female friends, downing a drink from a shot glass that had been placed on a bartender’s lap. Hawk then had accused Wirskye of trying to ruin her reputation so that she would be forced to resign, paving the way for Wirskye to be named as her replacement.

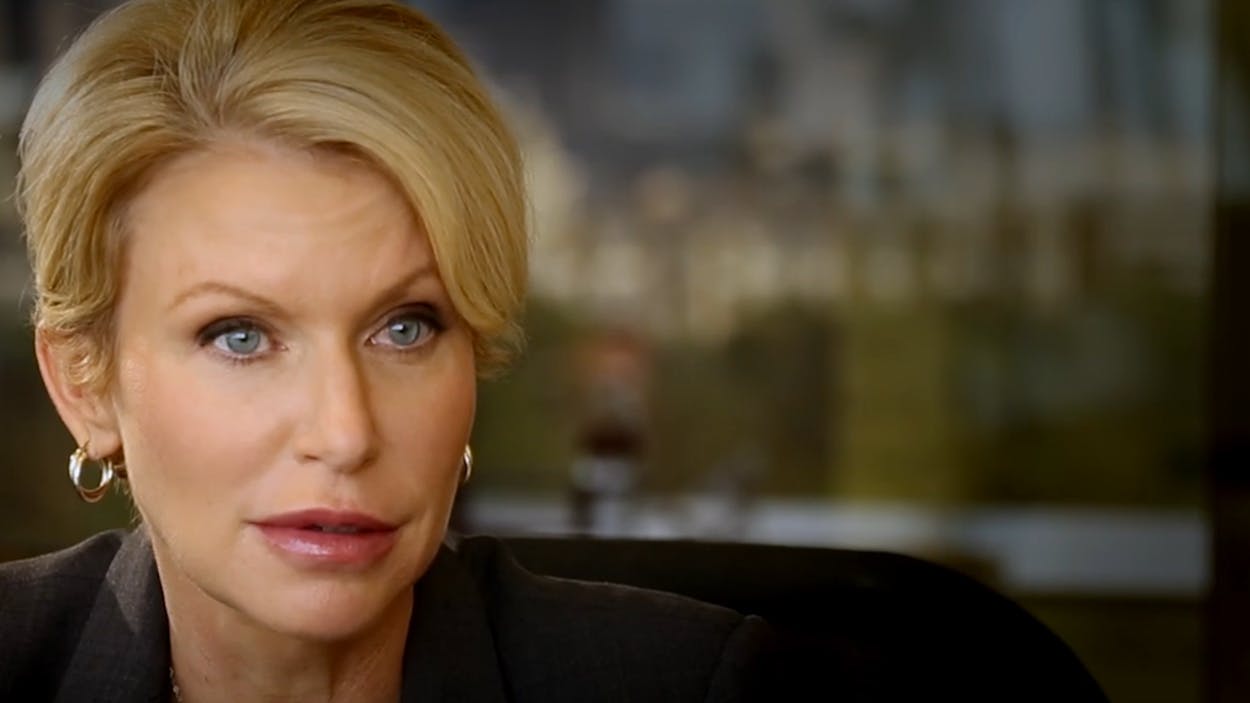

The lawyers at the courthouse couldn’t believe what they were hearing. The 45-year-old Hawk was a rising star in Texas politics who had defeated incumbent Craig Watkins the previous November to become the first female district attorney in Dallas County history. She had asked the 49-year-old Wirskye, one of the most respected criminal attorneys in Dallas, to be her first assistant, and he had given up his lucrative practice to work for her. At her swearing in ceremony after the election, he had served as the master of ceremonies, telling an exuberant crowd of supporters that a “new era of justice was about to be written for all citizens of Dallas County.”

But now, according to the rumor, Hawk was accusing him of treason. “In the hallways, people talked about nothing else,” one defense attorney would later say. “I mean, the whole thing was like something out of an episode of Law and Order or The Good Wife.”

A lot of people figured it was nothing more than just another tall tale invented by a bored lawyer with some time on his hands. But on March 23, the word spread that Hawk had fired Wirskye. Then the Dallas Morning News and local television station WFAA reported that what had happened between the two was much more than a tabloid-worthy scandal—it was part of a darker and far more disturbing narrative. According to their reports, some of Hawk’s close associates said she had become “unstable” and “overly suspicious.” Besides firing Wirskye, the stories noted, Hawk also had asked for the resignation of Jennifer Balido, another top lawyer in the office, whom she had accused of disloyalty. Hawk had even fired the office’s technology specialist apparently because she believed her office-issued phone and computer were being hacked.

Wirskye gave no interviews, but he issued a written statement declaring that he had not broken into Hawk’s home. The district attorney’s office, he said, had become “paralyzed the last few weeks by paranoia.” Balido did give interviews, and she went right after Hawk’s behavior during her first two and a half months in office, telling one reporter, “I observed a lot of indecisiveness, a lot of irrationality, and a lot of fear that was not based on anything that I could see would be rational.” Balido went so far as to say that she believed Hawk was suffering from “mood swings” that would change “from hour-to-hour or minute-to-minute.”

For her part, Hawk refused to discuss Wirskye’s alleged break-in of her home except to say that “something had happened and I asked him about it.” She said that she had fired Wirskye because they did not get along and that she had asked for Balido’s resignation because Balido was not the right fit for the job of administrative chief. She then said he did not see a “need to discuss this further” and that she was “focused on moving forward with the mission of this office.”

In fact, for the remainder of the spring, the district attorney’s office did indeed seem to move forward—at least it did until early August, when word spread through the courthouse that Hawk was no longer coming to work. On August 25, she released a statement announcing that she had been battling a “serious episode of depression” and that she would be spending another three or four weeks at an unnamed Texas treatment center. Her former political consultant, Mari Woodlief, told reporters that Hawk definitely would be back. “She wants to be the best DA she can be,” Woodlief said.

But as the weeks slipped by and Hawk remained out of sight, even her longtime supporters wondered if she would ever be capable of leading the District Attorney’s office again.

Mental health experts have long argued that Americans need to be less judgmental about mental disorders like depression. With proper treatment and medication, experts say, a person can manage even mental illness just as successfully as a person is able to manage a physical illness such as diabetes. But what if that person happens to be the chief law enforcement officer of one of the most populated counties in the country?

At this point, Hawk has not revealed the exact nature of her troubles—or how long they have been affecting her. Woodlief told me, “Susan has a very treatable depressive disorder which affects many Americans. She is dealing with it, and she will be an inspirational example for others who need to deal with it.” But Balido, who has known Hawk since the mid-nineties, believes that Hawk, at times, loses touch with reality. “I don’t even think Susan understands how severe her own mental illness is at this point,” she said. “This is not something where you can go to treatment and come back and think everything is all hunky dory. I would hope that it would be that easy, but anyone who has had any experience with people who are mentally ill know it’s not.”

Those who know Hawk at least agree on one point: something has changed. “I just wish you could have seen Susan before all this happened,” I was told by one of her friends. (Like many people I interviewed, the friend asked not to be identified.) “She was such a delight, so charming and charismatic. She was the kind of woman you could tell was going places. And now, the Susan I once knew isn’t there anymore.

Raised in Arlington, Hawk received her bachelor’s degree from Texas Tech University (she studied English and psychology), after which she enrolled at Texas Wesleyan School of Law, in Fort Worth. In 1995, right after graduation, she came to Dallas to take an entry-level job as a prosecutor with the district attorney’s office. She was initially assigned to the misdemeanor division, and she was so determined that she came to the courthouse on weekends, dressed in one of her trial suits to practice her presentations in front of an empty jury box.

In 1997, Hawk married a young defense lawyer, but the relationship was over within months, in part because she was so focused on work. She was promoted to a felony court, where she was regarded as a tireless prosecutor: one year, she served as the lead prosecutor in 27 jury trials, winning 26 of them.

In 1999, Hawk married again, to another defense lawyer, but that marriage lasted only a few years. Her career, meanwhile, kept gaining momentum. In 2002, the Greater Dallas Crime Commission named her “Prosecutor of the Year” for her work on child abuse cases. That same year, at the age of 33, she filed to run for judge of the 291st Criminal District Court and won. “Yes, she was very young, but she was a good judge from the first day she took the bench,” said Robert Hinton, a veteran Dallas defense lawyer who asked Hawk to officiate his second wedding. “She demanded that you be in her courtroom on time, ready to go. She challenged you on your evidence. Most of all, she gave you a fair trial.”

A few years into her tenure, Hawk started a program that was designed to help defendants who had been diagnosed with mental disorders. Instead of sending them to the penitentiary, where she knew their conditions would only worsen, she offered those who had committed non-violent crimes an opportunity to receive mental health services. She required those offenders to come to her court every Thursday so that she could make sure they were staying on their medications and attending their therapy sessions. The program, which she called ATLAS (Achieving True Liberty and Success), received awards from the National Association of Mental Illness and the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Hawk told a television reporter in 2009 that the court was her crowning accomplishment. “If I never do another thing,” she said, “it was worth that.”

I asked people who knew Hawk in those years if it was possible the reason that she was so compassionate toward mentally ill offenders was because she was privately struggling at the time with her own issues. They replied that they had never considered such a scenario because they had never seen Hawk act erratically. “Listen, this courthouse is teeming with a bunch of half-crazy lawyers,” one high-profile attorney told me. “Compared to those people, Susan came across as a saint.”

But by 2010, at least a couple of people in Hawk’s inner circle were growing concerned about her use of prescription drugs. One close friend who agreed to talk to me said that Hawk had acknowledged to her that she was taking hydrocodone (a narcotic pain medication) and an Adderall-like drug for attention deficit disorder. “And there were times when Susan’s personality seemed to be affected by the drugs—or by something. She would get really short with people for no reason at all. In the courtroom, she’d cut off lawyers or fly off the handle. And she was constantly asking me what people thought about her. She’d say, ‘What are people saying – good things or bad things? What have you heard?’”

Nevertheless, said the friend, “She didn’t have that many bad days. She was a successful judge doing good things for people.”

In 2012, Hawk married for the third time, this time to John Geiser, a Harvard-trained Dallas anesthesiologist. She continued to get good reviews running her courtroom. Then, in the summer of 2013, a group of Dallas Republican powerbrokers met with Hawk, hoping to persuade her to run in the upcoming 2014 elections against the incumbent district attorney, Craig Watkins, a Democrat who was seeking a third four-year term. In 2006, he had become the first black district attorney ever elected in Texas, and his subsequent work to exonerate wrongfully convicted prisoners earned him national attention.

But his tenure also had been dogged by controversies, including allegations that he had engaged in prosecutorial misconduct in a mortgage fraud case he brought against Al Hill III, an heir to the Hunt oil fortune. Although Democrats had won every contested Dallas County race for the past eight years, the Republican powerbrokers told Hawk they had done some polling and found that voters would choose a qualified female over Watkins. And now that she was remarried, she would be even more appealing to conservative women voters.

Hawk was already peeved at Watkins: apparently with his blessing, one of his top prosecutors had decided to run against Hawk for her position as judge of the 291st Court. She agreed to take on Watkins, and well-known Dallas Republican donors–Bob Dedman, Doug Deason, Trammell S. Crow, as well as numerous defense attorneys who didn’t like Watkins–quickly lined up to support her. In her campaign appearances, she talked about Margaret Thatcher being her political hero. (She said she especially loved Thatcher’s quote, “Disciplining yourself to do what you know is right and important, although difficult, is the high road to pride, self-esteem, and personal satisfaction.”) If elected, she vowed, she would “prioritize the prosecution of violent and habitual offenders.” She also declared she would “periodically appear in the courtroom to personally try some of the toughest cases in the office. Although running a large office effectively is a full-time job, I believe that by being in the courtroom, I can inspire my assistants, more effectively lead the office and regain the trust of our communities and citizens.”

But late one night in September 2013, according to sources who were then very close to Hawk, she sent some bewildering late-night texts to people she knew, telling them that she was being followed and that her Twitter account had been hacked. The next afternoon, while shopping at a Whole Foods supermarket with a friend, she started mumbling incoherently. Her friend drove her home. In Hawk’s purse was a bottle of Oxycontin (another narcotic pain reliever) along with her hydrocodone and Adderall. After talking to close friends, her husband and other members of her family, she agreed to go to the Meadows, a nationally renowned treatment center in Arizona that describes itself on its website as “the most trusted name in trauma and addiction treatment.”

But, the sources told me, Hawk insisted that her trip to rehab remain a secret. As a result, she told a Dallas Morning News reporter that she would be traveling to the East Coast to undergo back surgery and that a few weeks of rehabilitation would be necessary. “I’ll be stronger than ever when I get back,” she declared.

Some people who read her quote did find it odd that Hawk would want to travel so far away for the surgery when there were plenty of good back surgeons in Dallas, but nobody openly doubted her explanation.

By all accounts, when Hawk returned to Dallas in late October 2013, she looked much healthier. She spent the next several months campaigning vigorously. Her candidacy received an unexpected boost when the news broke that Watkins had used office forfeiture funds to settle a car accident that he had caused. “Mr. Watkins is the county’s top prosecutor, and he should be held accountable to the public,” Hawk snapped during one campaign appearance. “They [the forfeiture funds] are there to be used for law enforcement purposes only, not for Mr. Watkins’ slush fund.”

Then, in the fall of 2014, as the campaign heated up, stories began circulating that Hawk seemed to be distracted. She reportedly was having trouble concentrating on issues. She sometimes missed meetings. She told campaign staffers that she was concerned that Watkins had tapped into her computer and was having her followed. (A staffer went so far as to check the license plates of a car that she thought had been tailing her, only to discover the vehicle belonged to a 72-year-old woman.) During a public forum featuring her and Watkins, she acted uncharacteristically angry. When Watkins had trouble remembering exactly how long he had been in office, Hawk hinted that Watkins had a drinking problem, scornfully saying to him, “Have another cocktail.”

At that very time, Hawk’s marriage to Geiser was already falling apart. In the midst of the campaign, she moved out of their house and into a duplex. But once again, she said nothing publicly about the latest turn of events in her personal life, and the local press never picked up on it (or never reported it). “We kept telling ourselves that everything was going to work out,” one of Hawk’s friends told me. “Yes, looking back, we should have asked more questions and confronted Susan about what was going on. We shouldn’t have been such enablers. But we so desperately wanted her to win because we believed Watkins was running the DA’s office into the ground. And we thought as long as Bill [Wirskye] would be there as her first assistant, he could handle any problems that might come up.”

On Election Day, November 2014, nearly 400,000 Dallas County residents voted in the district attorney’s race. Hawk won by a slim 3,300 votes. That night, at a victory party at a Mexican restaurant, she was at her best, hugging her supporters and giving a rousing victory speech. She announced that in the first ninety days of her administration, she planned to try a criminal case to show that she was leading by example.

But she never got around to it. According to staffers I spoke with, Hawk seemed paranoid almost from the day she moved into the district attorney’s offices on the eleventh floor of the Frank Crowley building. She demanded that her office-issued computer and phone be replaced because she was convinced they were bugged. She asked another staffer to check and see if a tracking device had been attached to her car. She wanted to know if the fire alarm attached to the ceiling contained a camera.

What’s more, she didn’t seem to trust Wirskye: she asked him if he was using his cell phone to secretly record his conversations with her. She asked him why he was talking so much with Balido. And when she met with Balido, she demanded that she swear complete loyalty to her. “I did everything she asked me to,” Balido told me. “But even then, she thought I was hiding things. She would come in my office and say, ‘What’s going on? Is there anything you need to tell me? Something you’re not telling me?’ I would say, ‘No.’ Two hours later, she would come back in and say, ‘Is there anything you need to tell me?’”

In late January, Hawk fired Tommy Hutson, the technology director who had been with the office 21 years, claiming, among other things, that he had sent her mysterious photos of a black Tahoe. In February, she asked Balido to step down because she had failed to tell Hawk about some changes she had made to a routine court filing. On March 14, Hawk accused Wirskye of breaking into her home.

Wirskye demanded the chief investigators of the district attorney’s office come to Hawk’s office so that they could hear for themselves what she had accused him of. By the time they arrived on the eleventh floor, however, Hawk had backed off her accusation. Nevertheless, the story of the confrontation was soon racing through the courthouse. And within days, Hawk did another strange thing. She called an emergency meeting of her entire 450-employee office. In a rambling, impromptu speech, she lauded her employees for their accomplishments. Suddenly, she broke into tears. “I have heard there might be discussion about me or discussion about my personal life,” she said. “Some of you are not going to like me and I don’t care.”

Silent and bewildered, her staff stared at her as she continued to cry. Finally, she said, “If you have any discussion about me then I will be up in my office until 6:30 p.m. If you don’t come up and talk to me then I will assume that there is no discussion and that it ends there.” According to one person who worked for Hawk, only one or two employees came to see her. Everyone else “avoided her like the plague.”

After the meeting, Wirskye told a couple of confidantes that he was so worried about Hawk that he wanted to stage some sort of intervention. But he never got the chance. On March 23, Hawk told Wirskye she was firing him, claiming he hadn’t sent an email to staffers about the proper procedures for dealing with the media, as she had asked him to do.

When Wirskye and Balido went public with their statements about Hawk’s behavior, she went right after them, telling reporters that she needed top assistants who believed in her vision of what she wanted the district attorney’s office to become. She said that Wirskye had a “sense of entitlement” that prevented him from fully accepting her as his boss. “Transition is difficult,” Hawk added. “As you can imagine, in the first ninety days of an administration, people are going to talk.”

On that point, she was exactly right. More people did talk, including someone in her inner circle, about Hawk’s breakdown at Whole Foods and her trip to the Meadows. When Hawk was called for a comment, she did not confirm or deny the story. She only released a statement that said, “I have a serious back condition,” she said in the statement. “A doctor prescribed me medicine. Over a year-and-a-half ago, I decided I did not want to take it anymore, and I got help to quit taking it and haven’t taken any since.”

Hinton, the defense attorney and longtime friend of Hawk’s, decided to try again to stage an intervention. “It was clear to me that Susan had experienced a complete break in reality and that she was still in denial about it,” Hinton told me. But Hawk would not agree to meet with him. She also stopped speaking to several other colleagues who reached out to her. She did make a long-scheduled appearance at SMU to participate in a question-and-answer session with the dean of the law school, but she looked painfully anxious. When asked about her recent troubles, she said she had been through a challenging time and “when you stand on the truth, you never fall down.”

Hawk promoted two of her prosecutors, Messina Madson and Cindy Stormer, to take over as first assistant and administrative chief. To her credit, the office did run smoothly for the remainder of the spring. Hawk herself seemed more focused. She held town community town hall events in which she talked about her plans to bolster the office’s sexual abuse and elder abuse unit.

But in early June, she fired three employees in a single day: a long-time investigator, a forensic examiner, and a staffer who worked as a legislative liaison. The next day, she called a meeting of her top staffers. According to an interview that Stormer would later give to the Dallas Morning News, Hawk ordered everyone to turn off their phones and she said that “anyone running against me or helping someone who is running against me needs to get out now.” Stormer said that at another meeting, Hawk asked her to turn off her computer because “people can hear us.”

In August, Hawk stopped showing up for work. Mari Woodlief told reporters that she was taking much-needed time off after working long hours and on most weekends since January. Woodlief said that Hawk was physically and emotinally healthy and she denied rumors that the district attorney had returned to rehab. But by the end of the month, Woodlief had changed her story and acknowledged that Hawk was in treatment for depression at an “in-state” treatment facility.

When I spoke with Woodlief in early September, she told me that the tensions of the hard-fought 2014 campaign, combined with the pressures of taking over a demanding a new job and the personal challenges of dealing with her recent divorce, had made Hawk’s life “more and more stressful.” Although she would not discuss details about the nature of Hawk’s depression, she insisted that she was not being treated for prescription drug abuse. She also warned me to be wary of comments being made by other lawyers about Hawk’s behavior, claiming that some of those lawyers were hoping Hawk would be forced to resign so that one of them could be appointed District Attorney. “These guys were backing Susan in her campaign because they knew she was the only one who could beat Craig Watkins,” Woodlief said. “And now they are trying to get rid of her by making her look crazy. Believe me, Susan is not crazy. Her focus is on being a great district attorney.”

With Hawk embedded in a treatment center, life at the district attorney’s office once again appeared to settle down. Well, at least it did for a couple of weeks. On September 18, the news broke that first assistant Madson had fired administrative chief Stormer. Madson told reporters that in 2013, when Stormer was a prosecutor, she had badly mishandled a family violence case. What’s more, charged Madson, Stormer had failed to pay two important bills during her short tenure as administrative chief.

Stormer, however, suspected that Hawk had engineered her firing. She said that she had infuriated Hawk earlier in the summer by telling her that she could not use public funds to pay for certain personal expenses, such as lawyer association and Rotary dues, and that it was against county policy for Hawk to receive a credit card in her name, as she had requested. Stormer also said she had discovered the District Attorney had been supplementing another employee’s salary by taking $2,000 each month from the office’s hot check fund, which Stormer had told her was “improper.” With her firing, Stormer declared, “there is now nothing between her [Hawk] and the public funds.”

Madson snapped back, “I’m not going to dignify any of this with a response.”

Today, everyone in Dallas is waiting to see what will happen next. Around the courthouse, there is lots of talk that even after spending a month or so at a treatment center, Hawk is not ready to come back into a high-stress job. Some lawyers believe that she has caused so much damage, especially by misleading the public with her back surgery story, that she should resign or be removed from office. Under Texas law, a citizen can file what is known as a “removal suit” in a district court. But the reason for removal must be due to incompetence, official misconduct, or intoxication on or off duty caused by drinking an alcoholic beverage. Although Stormer has said she is considering filing such a suit to have Hawk removed, her chances of getting a judge to accept the case and bring it to trial are small. Hawk’s lawyers could drag out the case for months, arguing that the District Attorney is not incompetent but only being unfairly stigmatized simply because she has depression.

And what if it turns out that Hawk is in much a better place emotionally and mentally? What if she has learned to manage whatever it is that afflicts her? That’s certainly what Hawk says has happened. On September 21, she sent an email to her staff about her upcoming return, “I want you to know that I am healthy, and I have a plan to stay that way.” In another statement to the news media, she added, “I did not choose to have a mental illness, but I did make the choice to confront it and take on the hard job of recovery….I look forward to being back. I’m excited to get to get to work….And I look forward to continuing to serve our communities while we continue to make our office the most respected DA’s office in the nation.”

In her email, Hawk said she will return to her office on October 2. (It now appears she that may be back on the job as early as Thursday, October 1.) A lot of people who know her are convinced that if she does return, there will just be more chaos to come. But others want to give her a chance. “Its’ going to be tough,” said Hinton. “Everyone is going to be watching her closely. But if she keeps it all together, I have no doubt voters will embrace her. She could be one of the greatest comeback stories anyone has ever seen.”