“Somebody planted the sonuvabitch.”

That was one organizer’s immediate assessment after a bomb threat forced about 75 bikers and supporters to disperse from in front of the McLennan County courthouse Saturday morning. The bikers had organized a memorial for the nine people killed at the Twin Peaks shooting in Waco three months ago, but the gathering was also supposed to serve as something of a rally for the 177 bikers arrested that day. But now, thanks to a suspicious cooler and a suitcase, the group dissolved.

Clint Broden, the lawyer most publicly associated with the case, was scheduled to speak. And from the sounds of it, Broden’s address could’ve been illuminating if he’d had the chance to give it—”I will have a lot to say soon, I have been saving it up,” he promised on the event flyer.

It’s still unclear what happened on May 17. Most of the national attention the shootout between cops and bikers garnered focused on the two clubs involved, the Bandidos and the Cossacks—essentially turning into PR campaigns for both sides, with law enforcement and bikers offering two very different interpretations of biker culture.

There appears to have been something of a turf war between the ruling Bandidos and the upstart Cossacks, but of the 177 arrested, few had any criminal convictions in Texas. But it’s certainly clear law enforcement had their eye on the Bandidos and the Cossack, having issued a bulletin warning about escalating violence between the two clubs in Texas. The animosity, and sometimes outright wars, between outlaws and the lawmen, has been raging since bikers first hit the road shortly after World War II. Confrontations between clubs with cops are well documented (see: Hunter S. Thompson’s Hell’s Angels). Police have contended that biker gangs run drugs, among other illegal activities. As biking culture has become more mainstream, bikers have argued that their clubs are just that — a group in which like-minded people can talk shop and do what they love.

Details about what happened during this specific shooting, and the subsequent legal issues, are slim. Much of the scarcity of information can be attributed to the courts, which have a gag order in place for all parties involved in the proceedings. The order has been officially protested by a group of sixteen media organizations and is currently in legal limbo, awaiting a decision from the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals.

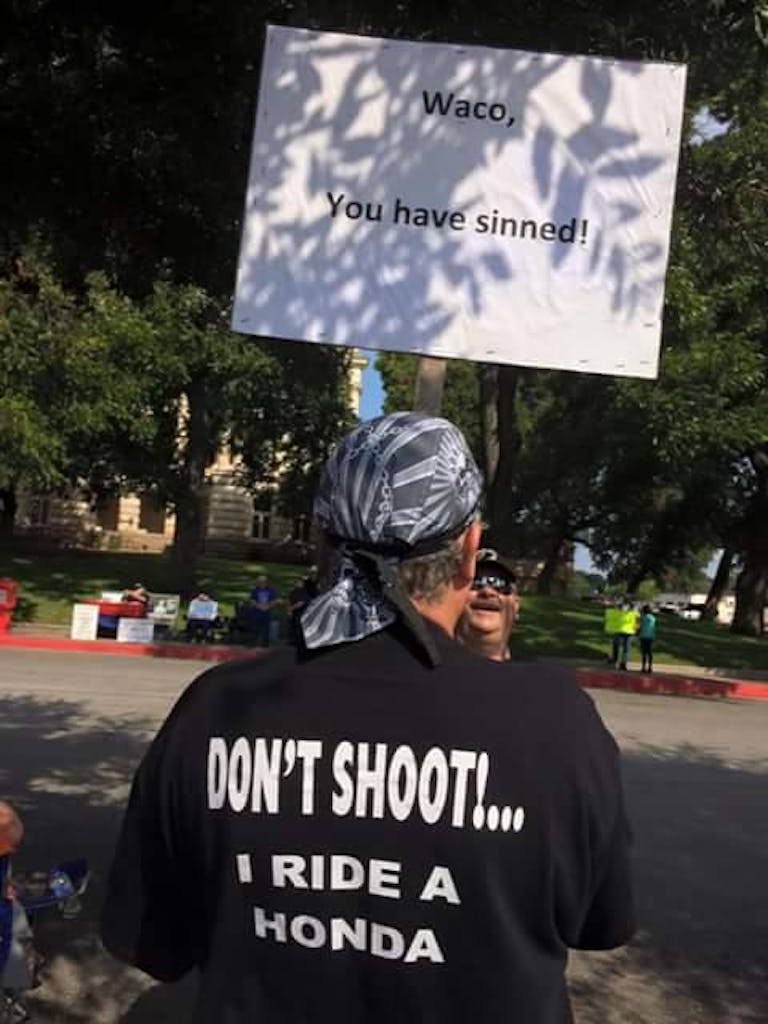

But that hasn’t put the brakes on personal investigations by club bikers and supporters, which have resulted in a budding patch of uneasy theories. From the conversations at the McLennan courthouse, it’s clear the bikers have developed their own narrative for what really happened, one in line with familiar anti-establishment types. For instance, there were T-shirts that referred to the incident as the “Waco Massacre.” And this one:

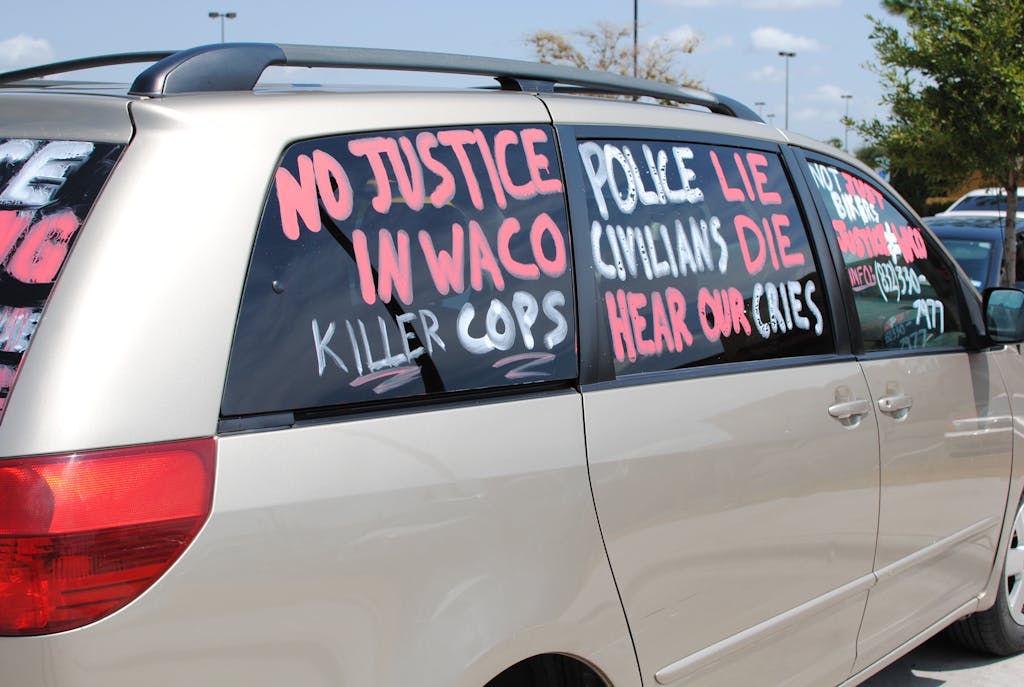

Or this van:

And there was this couple. When I asked what they were looking at, they said they were trying to figure out how many people were on top of the ALICO, a 22-story building towering over the main square. The suggestion was that there was police surveillance up there (somebody was up on the roof, that’s for sure). Possibly a sniper.

It sounds fantastical, but that’s one of more consistent aspects of the bikers’ explanation of what happened at Twin Peaks. In a nutshell, their story is that the cops planned the whole operation. It was a turkey shoot, they say.

After the bomb threat, the gatherers quickly dispersed (and pretty quietly, for bikers). Some reportedly left town immediately, some congregated in areas just down the street from the courthouse, and others met at the local Harley-Davidson store. I followed John Bostick to Twin Peaks, where a group of about a dozen had gathered.

Bostick, a national administrator for 2 Million Bikers to D.C. who lives in Athens, had organized the twenty-strong crew that rode down from Arlington following an empty white hearse. The group formed in 2013 for two reasons—to “commemorate 9/11 victims and military veterans,” but also to protest the American Muslim Political Action Committee’s . . . rally on the National Mall,” according to Time magazine. As gatherers milled around the Twin Peaks parking lot, the Confederate flag came up, with one biker positing that banning it is destroying history, and that even a black friend he knows isn’t offended by it; another discussed how, contrary to the official story, authorities had actually used explosives during the Waco siege of 1993 with the Branch Dividians. The gathered group doesn’t always have views that the mainstream finds particularly sympathetic.

“Matthew Mark Smith was there,” said Cara Edberg, pointing to the sidewalk behind the now-shuttered Twin Peaks. “You wanna know where people were? I found all nine bodies.” The club supporter had traveled from her home in Longview, Cossack territory, and was guiding others to the spot behind the restaurant where 27-year-old Cossack member Matthew Mark Smith died from gunshot wounds to the stomach and back.

In a way, Smith was being mourned. But as people gathered around Twin Peaks, he seemed to also be a representation of something larger, a catalyst for supporters’ anger, pain, and frustration.

Edberg kept using Matthew Mark Smith’s full name. Said repeatedly, it had the ring of a mourners’ mantra to it. Bending down to the place where the bullet went into the metal siding, people examined it meticulously, expertly. They kept judging the trajectory of the bullets like members of a forensics team on some TV procedural. Everyone was fairly quiet, a bit somber, as they circled the building, inspecting the bullet holes dug into the rock wall and concrete.

“Tell me that bullet hole didn’t come from a high-powered rifle,” said one woman evaluating the crime scene. “Oh hell yeah, it did,” another woman responded. Young kids ran back and forth between the parking lot and the side of the building, repeating the names of the dead.

Mary “Betty Boop” Rodriguez stood beside bullet holes in the concrete, marking the place 65-year-old Purple Heart recipient Jesus Delgado Rodriguez had been shot and killed. Watery-eyed and mostly silent, the widow was surrounded by family. “Mohawk” and “Betty Boop” had been married for forty years.

“I’ve got a couple of the widows that I speak to,” said Edberg. “You know, this is hard; this is a really hard time. They were regular guys. They had families and grandkids on the way.” And the sorrow is turning into bitterness, among other things. “It feels to us almost, like, they portrayed us as trash. Like, we don’t deserve any kind of respect. And that really hurts. I lost my fiancé [who was in a biker club] four years ago. These bikers, they’re all I know. They took care of me and my family. They held me up.”

Anger and the desire for justice seem to be holding the community up too. The bikers explain how a supposed sniper, using a high-powered firearm with a sound suppressor, was atop the adjacent Don Carlos restaurant. And there are plenty of other theories about the incident. On the radio, officers could allegedly be heard saying, “the A side” and “the B side,” of the Twin Peaks building, clear signs, according to Bostick, that they’d “been all over this on the chalkboard for two months [prior].”

Bostick went on to explain part of an hour-long video that’s been making the rounds on the Internet, silent surveillance footage from Don Carlos. One biker was tied and left under the care of a single SWAT member for over an hour before being let go—the cops’s inside man, said Bostick. Then, Bostick pulled up a 59-second cell phone video taken from inside Don Carlos. “If you listen to it, right off the bat, you hear tch-phff, tch-phff, tch-phff.“ That noise, he said, were the “sniper rounds with a suppressor. . . . They started pickin’ them off.” I listened to the video, putting my ear close to his phone. I think I heard it.

Some of these claims seem plausible enough, or, at the very least, not entirely unreasonable. Maybe a couple are hard to follow, and there are aspects to the case that even the bikers disagree about. But the fact is, the lack of official information leaves bikers with only their theories and their anger. Even respected legal writers are frustrated with how things are progressing. At Above the Law, law professor Tamara Tabo laid out exactly why “You Haven’t Heard More About The 177 Bikers Arrested In Waco” (fun fact: the original judge who had set the sweeping, $1 million bail for all those arrested is a former state trooper who thought it was “important to send a message”). And the acclaimed criminal justice blog Grits for Breakfast (recently profiled in Texas Monthly) has highlighted the fact that the “randomly” chosen jury foreman is a current Waco police detective.

So had the cooler planted to break up the memorial, or was it just a coincidence? The bikers’ knee-jerk suspicion might be significantly decreased if authorities had been treating this case with transparency. Confusion and panic during and immediately after the incident were real, and the courts putting everyone in lockdown mode makes some sense (newspapers warned the apocalypse was about to reign down, a horde of bikers en route to the scene). Since the beginning, authorities have advised against listening to what they call conspiracy theories, telling reporters, “We can’t wait to show you what truly happened.” But after three months basic questions about the incident still aren’t being answered, and they should be. Because for the family and friends of the nine dead and the 177 arrested, nothing about this series of events has been easy. Just awful.