From the time he left the British oil giant BP, in 2006, John Hoffman dreamed of starting his own oil company. But his timing was terrible. He formed Houston-based Black Elk Energy in late 2007, as oil prices were beginning their run toward a peak of $147 a barrel; drilling prospects were selling at a premium, which made financing difficult for a small, untested company. Nevertheless, Hoffman had a lot going for him. His background as a 25-year veteran of Amoco and BP, where he served as an operations manager in Egypt and elsewhere, was impressive. And he had a smart business plan: Black Elk hoped to buy shallow-water wells in the Gulf of Mexico that other companies had given up on and rework them to squeeze out the remaining drops of oil. That was enough to convince a Connecticut investment bank to put up some money so that Black Elk could buy offshore leases.

Then the global financial crisis hit, and the money dried up almost overnight. “We knocked on hundreds of doors over many months,” Hoffman says. “We were walking into banks as employees were walking out with boxes of their belongings.” Eventually, someone mentioned to him that the New York hedge fund Platinum Partners wanted to invest in oil companies. Hoffman set up a meeting with Platinum’s managing director Dan Small and later its chairman and chief investment officer Mark Nordlicht.

It appeared to be a great fit. Platinum claimed to be one of the world’s best-performing hedge funds, generating returns of about 17 percent, all of it from small, obscure companies. Nordlicht offered $50 million in loans to Black Elk, but at a hefty price: 20 percent interest. That wasn’t all. The loans had special provisions that allowed Platinum to increase its ownership of Black Elk over time. For someone else, those conditions might have raised a red flag. But Hoffman, who grew up in the lead-mining town of Desloge, Missouri, where a handshake deal was considered rock solid, wasn’t worried about Nordlicht. “He seemed like a man of his word,” he says.

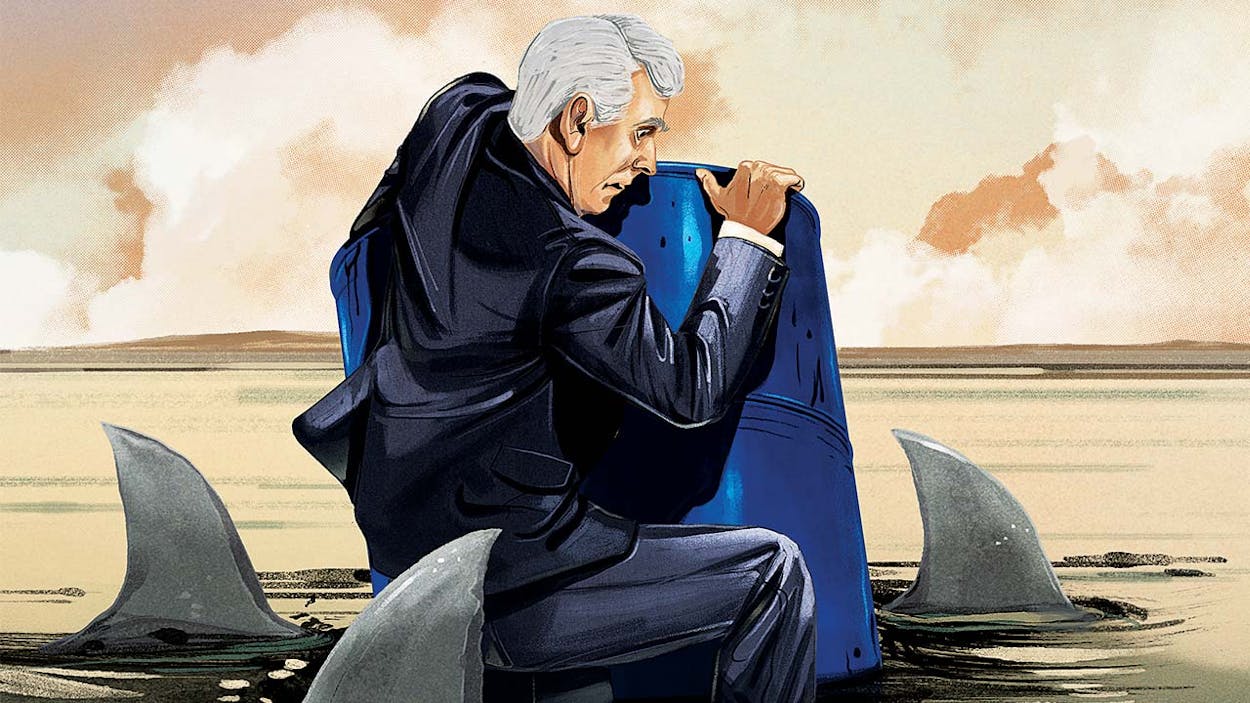

However onerous the terms of the Platinum loans, they enabled Hoffman to buy enough offshore assets to get the company going, and two years later the hedge fund arranged a $150 million bond sale to support even more growth. By late 2011, Black Elk had 241 production platforms on more than 293,000 acres in the Gulf, with reserves worth more than $1 billion. Its daily oil and gas production averaged 14,500 barrels, and things seemed to be running full speed ahead. What Hoffman didn’t realize was that he had gotten into bed with a company that didn’t share his Midwestern handshake values.

With Black Elk, Hoffman was trying to create the kind of company he had always wanted to work for. After a quarter century in big corporations, he envisioned Black Elk as a familylike environment free of company politics and bureaucracy. Although Black Elk was privately held, he gave employees equity so that they could share in its success, offered them free gym memberships, and covered their health insurance premiums. In November 2012, Black Elk made the Houston Chronicle’s list of the city’s top workplaces based on ratings by its employees.

Those accolades came from employees at the company’s headquarters in Houston. On its platforms in the Gulf, though, it was a different story. Between 2010 and 2012, the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) cited Black Elk’s operations 315 times for rules violations and risky procedures. Hoffman says that many of those violations were minor and unrelated to drilling operations. He also claims that there were so many violations because the company was growing rapidly and that on a per-platform basis, its safety record was improving. “We were not a bad actor in the Gulf,” he says. “We had some contractors that did some things that were against our policies.”

All of this came to a head on November 16, 2012, just five days after the Chronicle had lauded the company for its worker-friendly environment. That morning, a series of explosions rocked Black Elk’s West Delta 32 platform, off the coast of Louisiana. Workers welding a flange onto a pipe ignited flammable vapors, touching off the explosions, which blew two of the platform’s oil tanks into the Gulf and knocked another off its base, destroying a crane on the platform. About 480 barrels of oil spilled into the water, and oil rained down on the platform’s lower decks, where other workers were doing maintenance procedures. Three rig workers employed by a subcontractor died, and two others suffered severe burns.

As the operator, Black Elk was responsible, even though the workers weren’t company employees. In the oil industry, welding is known as “hot work,” and it requires a special permit because of the proximity of explosive fluids and gases. A BSEE investigation found that the relevant hot-work permit was never issued for the West Delta platform and that “a number of decisions, actions, and failures by Black Elk” and its contractors caused the deaths. BSEE concluded that the failures represented “a disregard for the safety of workers on the platform and are the antithesis of the type of safety culture that should guide decision-making in all offshore oil and gas operations.” Three years later, federal prosecutors charged Black Elk—though not Hoffman or any other executives—with involuntary manslaughter and other charges related to the safety violations that led up to the accident as well as the environmental damage that resulted from it. The company pleaded not guilty, and the case is still pending. “My heart goes out to those families,” Hoffman says. “You can never replace a life.” Black Elk reportedly settled all civil legal claims involving the accident and compensated the families of the victims.

The explosion, the worst accident in the Gulf since BP’s Deepwater Horizon disaster, didn’t simply draw attention to Black Elk’s questionable operating history. Because all the victims of the explosion were Filipino nationals, it also cast a spotlight on the practice of funneling Filipino workers to offshore rigs under a system that the workers claimed in a federal lawsuit was akin to slavery. At the time of the Black Elk accident, more than 150 Filipino nationals were working on rigs in the Gulf, recruited by companies that lured them with promises of as much as $24 an hour for overtime pay. Once they arrived, however, they were told that the pay would be $5.50 an hour, and they would have to cover their housing costs and fees for using the equipment they needed do to their jobs, according to a lawsuit filed by twenty of the workers against several companies involved in hiring them and bringing them to the U.S. The defendants included Grand Isle Shipyard, which Black Elk hired for rig work. The workers claimed they weren’t allowed to leave their crew quarters during their off hours except for brief supervised trips to Walmart each week. Hoffman claims he was unaware of the conditions at the time. (The lawsuit was settled in 2014, following the dismissal of many of the charges against Grand Isle. The terms of the settlement are confidential.)

By this point, Black Elk no longer looked much like the wonderful company Hoffman had envisioned. Its reputation had taken a big hit, its finances were in disarray, and its growth plan had stalled. And so Hoffman turned once again to Platinum Partners.

In 2003, Mark Nordlicht, a commodities trader who once held a seat on the New York Mercantile Exchange, formed Platinum with Murray Huberfeld, a former principal in Broad Capital, a New York investment firm that specialized in merging private companies with public shells, a cheap way for a small company to get a stock listing. Huberfeld had pleaded guilty to securities fraud in 1993, and he and Broad Capital had had several run-ins with the Securities and Exchange Commission in the nineties. (Last year, he was arrested and charged with bribing the president of the New York corrections officers’ union to invest $20 million with Platinum. The trial is scheduled for October.)

Perhaps because of Huberfeld’s shady background, Platinum never attracted many professional investors. Instead, it marketed itself primarily through a network of businesspeople with ties to Nordlicht and Huberfeld. Platinum’s strategy, at least on paper, was to invest in companies that other investment firms shunned. It owned stakes in thinly traded pharmaceutical firms, payday lenders, Singaporean penny stocks, and a Congolese diamond mine. They all had one thing in common: they were small companies desperate for cash and willing to agree to the fund’s burdensome terms.

“This is their standard playbook,” says Michael Petras, a California entrepreneur who spent years investigating Platinum after he claims it destroyed his retail power company. “There were many founders of companies who did the same thing Hoffman did. They got sucked into these loan-to-own strategies. Once you’re on their treadmill, you can’t

get off.”

After the 2012 explosion in the Gulf, Black Elk’s bank lenders demanded more collateral for a revolving credit line, forcing the company to raise cash by selling assets. Hoffman flew to New York in early 2013 with a plan for getting the company back on track by buying as much as $120 million worth of new wells. Platinum agreed to provide the money, and Black Elk hired a drilling company for $90 million. Four months later, Platinum told Hoffman it was having problems with other companies in its portfolio, and it couldn’t come through with the loan. “That was the death blow,” Hoffman says.

No one else wanted to lend Black Elk money until it resolved the legal ramifications of the accident. As the company slid toward insolvency, Platinum pressured Hoffman to put it up for sale so that the fund could cut its losses. Hoffman also found himself in a power struggle with Jeffrey Shulse, the founder of a company, later acquired by Black Elk, that provided plugging and abandonment services for offshore wells. Platinum, which had used the covenants in its Black Elk loans to increase its ownership to more than three fourths of the company, ordered Hoffman to make Shulse chief financial officer. Then, Hoffman claims, Shulse began making end runs around him and dealing directly with Platinum. He claims he tried to fire Shulse three times, but each time Platinum reinstated him. Shulse denies this. Says his attorney, Andino Reynal, “What Mr. Hoffman says is not consistent with reality or the facts.”

Shulse found a buyer willing to pay $170 million for Black Elk’s assets, but it didn’t appear that the deal would help Platinum. Most of the money would go to the owners of the bonds Black Elk sold in 2011, which had covenants that gave them first rights to any sale proceeds. Platinum, as the preferred stock holder, was next in line. Yet the hedge fund was desperate; it was no longer paying out its trademark double-digit returns, and investors were demanding their money back. “This is code red,” Nordlicht warned another Platinum executive in an email. If all the proceeds from the asset sale went to the bondholders, the value of Black Elk’s preferred stock would fall, worsening Platinum’s cash crunch. It needed a way to get that money for itself.

Platinum instructed Black Elk to call for a vote asking bondholders to surrender first dibs on the sale proceeds. Hoffman wasn’t worried, because he figured investors would never vote to surrender their rights to a return. As the private equity holder, Platinum, which publicly claimed to own $18 million worth of Black Elk bonds, was prohibited by SEC rules from voting on the waiver.

What Hoffman and the other investors didn’t know is that Platinum, in violation of federal disclosure laws, had been secretly buying up Black Elk bonds through a series of companies it controlled. Through these companies, Platinum controlled about $98 million, or roughly two thirds, of the Black Elk debt, and it used that power to approve the waiver in August 2014. Given its bond-buying spree, Platinum would have captured most of the proceeds from the sale, but it needed the money in the right place—Black Elk’s preferred stock—which would enable it to increase the return for its investors. (Most of the bonds, held by the companies it secretly controlled, wouldn’t show up on Platinum’s books.) Nordlicht then instructed Shulse to send the fund almost $100 million from the asset sale. Shulse did so, and also paid himself a $275,000 bonus, telling the hedge fund that “Platinum getting its money out of Black Elk is a good thing for Platinum and it should be a good thing for me as well.”

Hoffman, meanwhile, found himself locked out of the company offices. With Platinum’s blessing, Shulse took control as CEO and laid off most of Black Elk’s employees. As a final indignity, the employees, who were equity owners, discovered that they would owe taxes on the proceeds from the asset sale, even though they had received none of the money. Hoffman says he didn’t understand what had happened until he saw the company’s final financial filing in September 2014 showing the cash payment to Platinum. “That’s when I discovered they took it all,” he says. In 2015, some creditors, including contractors who hadn’t been paid, filed a petition to liquidate Black Elk in bankruptcy, hoping to recover some of what they were owed. But there was little left.

As for Platinum, its ransacking of Black Elk was too little, too late. In June 2016 it ran out of cash to pay investors, and later that summer federal agents, working from the information that Michael Petras had spent years gathering, raided its New York offices. The fund filed for bankruptcy in October, and in December the U.S. attorney’s office in New York indicted Nordlicht, Shulse, Small, and four other Platinum executives on eight counts of fraud and conspiracy. Essentially, the feds accused Platinum of misrepresenting its financial status in order to bring in new investors whose money would then be used to pay back earlier investors who were clamoring to get out. U.S. Attorney Robert Capers said that Platinum’s six hundred investors lost an estimated $1 billion, making it the biggest Ponzi scheme since Bernie Madoff. Platinum’s executives have pleaded not guilty. “Jeff [Shulse] is innocent of these charges,” Reynal says. “This is a case of overreaching on the part of the government.”

Hoffman has tried to put the nightmare of Black Elk behind him, but it isn’t easy. He’s attempting to start over with a new company, P3 Petroleum, but Black Elk’s demise, and now the Platinum indictments, have scared off many potential backers. Still, he’s hopeful, if a bit chastened. “We’re trying to do it wiser this time,” he says. “We have no debt.”