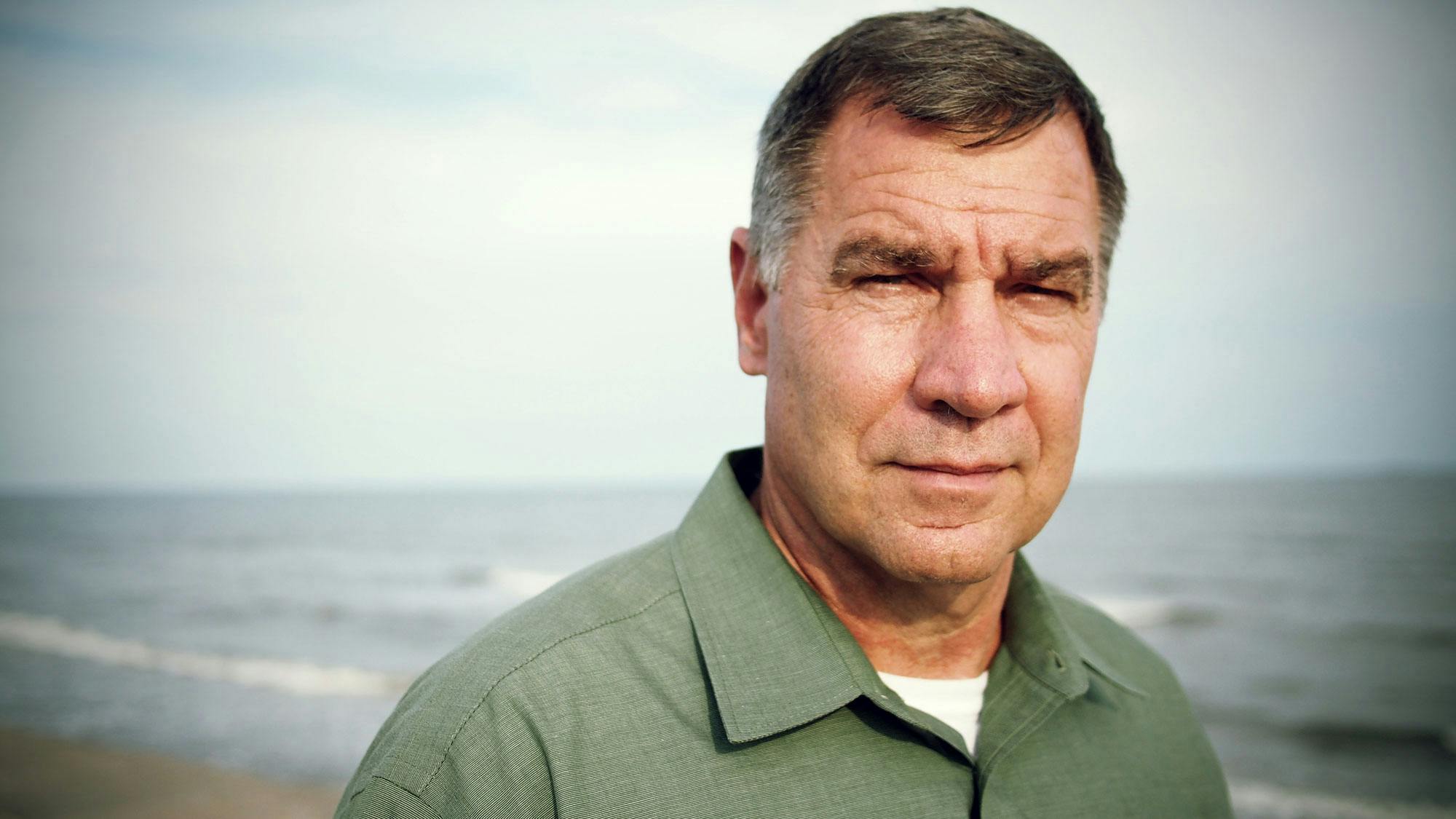

Fred Paige and I are standing at the edge of a vast swamp, near where two bayous converge just south of Dickinson. It is 11 a.m. on a Saturday in August 2015, and the temperature is already pushing 100 degrees. Paige, a big-hearted ex-homicide detective, had driven his oversized black pick-up down a private road that once belonged to Humble Oil and parked on the sandy shore not far from the salty waters that lie between Houston and Galveston. He’s returning to the scene of a crime.

It was on this piece of land, 44 years before our visit, that someone unlocked a gate and drove toward Turner Bayou with best friends Maria Johnson and Debbie Ackerman, two teenaged girls from Galveston Island. For decades, their murders have been unsolved.

We have agreed to meet at this spot to review the details of the case because Paige suspects—and I have come to believe myself—that there is a likely suspect, not only for the island girls’ murders, but ten other long-unsolved killings. Paige first learned about the Johnson and Ackerman case ten years ago, when he was a homicide detective in Galveston. He had eventually obtained a copy of a long-forgotten confession letter, in which a convicted killer accurately describes details of the killings and of this desolate place. “Dear Sir,” the handwritten missive to the Galveston district attorney begins. “I have decided to tell you that I was ‘brainwashed into killing Deby [sic] Ackerman and Maria Johnson in November 1971.” The man who wrote the letter, Edward Harold Bell, was never questioned by the police. Bell is an eccentric and violent convict who remains in a Texas prison today for another murder.

As we wander the site, the sky grows dark with clouds, and lightning flashes twice on the horizon. Paige doesn’t seem to notice—he’s thinking about Debbie and Maria. He recites details from the police reports as we walk together down the road toward a wooden bridge. His memory for names, dates, and details is incredible, even though the double murder was not originally his case. Paige recounts how the killer drove down this unpaved caliche road, which has remained mostly unchanged since 1971, lined with old oilfield equipment, grazing cows, and capped wells. The murderer then marched or carried the two girls out on a rough-hewn bridge that straddled a narrow stretch of Turner Bayou. Their hands were tied. They’d been stripped of most of their clothing. He forced or threw them into the water, which, depending on the tides, is about waist deep. Then he shot them dead with a .38-caliber pistol at close range.

Paige, whose sandy brown hair is flecked with gray, is in his mid 50s and was a small boy living in Central Texas when the two girls disappeared. He inherited their case when an old woman who’d been friends with Debbie Ackerman’s mother called the station, and he happened to pick up the phone. Since then, Paige has immersed himself in it.

He’s tracked down Debbie and Maria’s old crowd. Many remember Debbie as a champion water skier and island native —a BOI—who trained at Wix Ski School on Offatts Bayou. Maria was the new girl, a pretty teen who moved to Galveston after her parents divorced and quickly became Debbie’s best friend. None have forgotten how they vanished. “On November 14, 1971, on a Sunday, Maria and Debbie came into a Baskin & Robbins store and bought ice cream,” one classmate’s statement says. She remembers seeing them disappear into a “white van with a man driving it.”

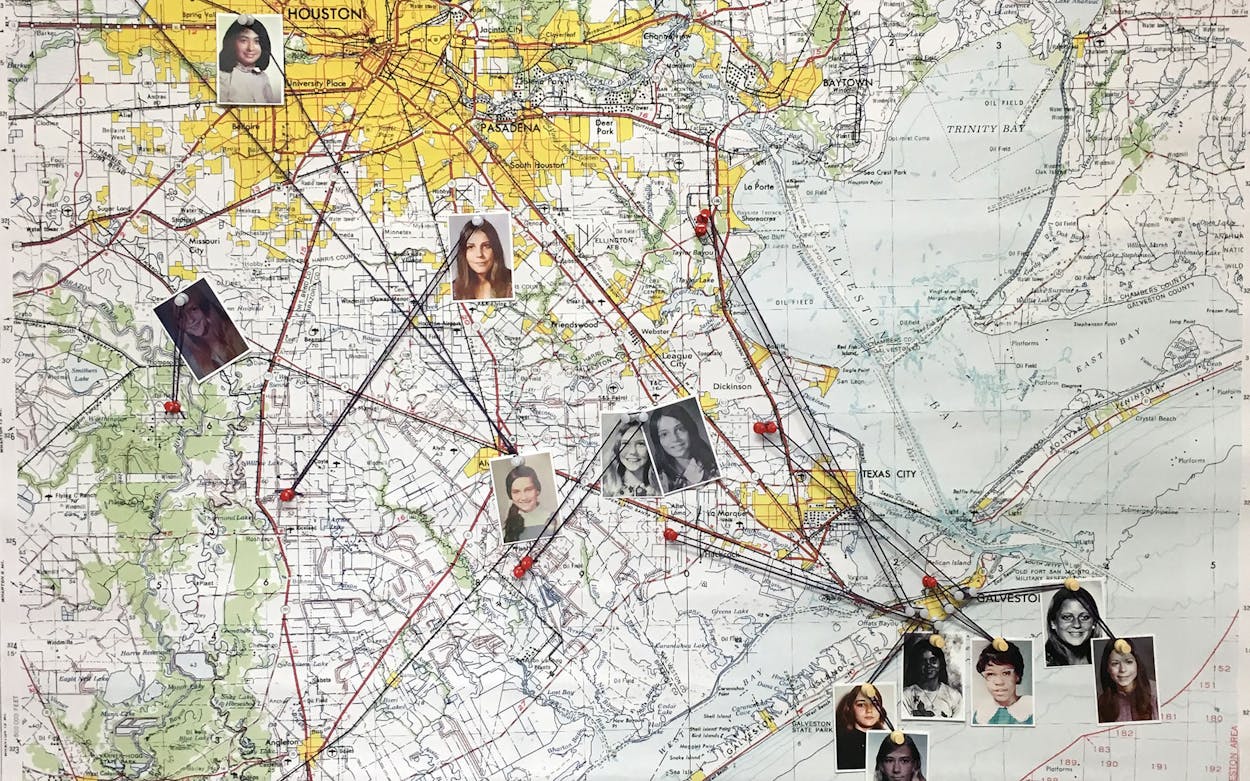

The girls’ disappearance changed the lives of islanders. It created a panic that made front page news first in Galveston and Houston and eventually across Texas. Even as a schoolboy, Paige heard about the crimes. Debbie and Maria were among the first to disappear, but they were not the only pair of friends to be abducted and killed. The skulls and scattered bones of two Webster surfer girls—Sharon Shaw and Rhonda Rene Johnson—who’d also vanished from the island that summer were found a few months later in another marsh only a few miles away. Then more skeletal remains turned up that belonged to two girls who’d been snatched in the tiny town of Dickinson: Brooks Bracewell and Georgia Geer. Brooks was the youngest of the victims, only 12. Other slim girls with long hair were abducted and murdered between 1971 and 1977 too. They came from Alvin, Dickinson, Webster, Houston, and Galveston. In all, there are eleven victims whose cases remain unsolved.

I first met Paige while reporting for a 2011 series for the Houston Chronicle about a backlog of hundreds of unsolved and unidentified murder victims in Harris County forensic files. Paige told me about Bell, and about the secret confession letters Bell sent prosecutors in both Harris and Galveston counties. I did some digging and found a long trail of real estate records, handwritten court ledgers, and prison logs that confirmed Bell had lived or been arrested in remote areas near where girls disappeared and where bodies had been found. Two other retired investigators told me Bell was the strongest suspect they’d ever identified, but he had refused to cooperate.

I wrote Bell and was shocked when he agreed to an interview. Bell is a graduate of Texas A&M University and a proud former cadet and member of the Aggie Marching Band. He’s gregarious, and fancies himself a poet. He’s also a serial sex offender whose victims of choice are teenaged girls, according to old rap sheets that detail incidents from West Texas to Louisiana. But he’s serving time for the 1978 murder of a man named Larry Dickens, a Vietnam veteran who confronted Bell when Bell accosted a group of neighborhood girls near the Dickens’ home in Pasadena. As Dickens’ mother watched from a kitchen window, Bell shot her son multiple times with a .22. Once Dickens fell, Bell had gone back to his red GMC pickup, retrieved a rifle he carried, along with piles of paperwork and porn, and returned to finish off his victim.

Bell first agreed to talk to me at Navasota’s Pack Unit in July 2011. When I met him, he was gaunt, deaf, and more than 70-years old. He eagerly greeted me as if I were an ally, confiding that it was a government “program” that made him into a rapist and a killer. Since then, we’ve had a series of bizarre conversations. In chilling interviews and in odd sporadic letters and poems, Bell recounted his life story in mesmerizing and strange detail. He confirmed that he authored confession letters to prosecutors. In one of his letters to me, Bell claimed he’d killed eleven girls; he called them “the Eleven who went to Heaven.” I wrote about Bell’s revelations in my series for the Chronicle, but I was unsure what to make of them. Bell knew a lot about unsolved murders from the 1970s, and he was clearly a sociopathic sex offender looking for a thrill. But was he really an unpunished serial killer? Or just a masterful liar with an incredible memory?

Despite Paige’s dogged investigations, Bell had never been charged with the murder of Debbie Ackerman and Maria Johnson or any other girls. No one had ever uncovered iron-clad forensic proof of Bell’s guilt. So, in the summer of 2015, Paige and I had agreed to try to find that proof—if it existed.

Bell was getting old. We knew he could be released on parole or die without providing any more information. That bothered us. The families and friends of the victims deserved answers and justice.

Paige and I would have to investigate on our own time. He had retired from the Galveston Police Department, and my newspaper editors weren’t interested in investing more resources in such an old case. Despite all of Paige’s work and mine, there were still many leads we had never chased, including witnesses who had been too far away or proven too difficult to find.

As we stood at the murder scene that Saturday in August 2015, Paige began talking about “secondary crime scene sites” we might discover by tracking down Bell’s ever-changing addresses. I thought we might find down Bell’s 1971 white Ford van or uncover evidence stored in some long-forgotten warehouse that might contain a DNA fragment and solve the murders once and for all.

Neither one of us really believed Bell was lying about everything. In the 1970s, Bell co-owned a surf shop on Galveston Island and he knew both Debbie and Maria. On the way to meet Paige, I’d drive past a pasture on the other end of rural Humble Camp Road where Bell and his second ex-wife had once kept a bright red camping trailer that looked like a railroad caboose. That site was less than five minutes away from where we stood.

We both wanted answers. And so we decided to not only investigate together, but to allow our efforts to be documented by a film crew. Because after more than four decades, we figured the only way to obtain justice for the eleven victims might be to share our findings with other Texans who could help us. The result is The Eleven, a five-part documentary series that premieres Thursday night.

As we returned to Paige’s pickup, the eerie oil field road and the murky waters there still seemed to hold the secret of the killer’s identity. We drove back down that caliche road. As we reached the gate at the exit, a large tree fell, sending a neighbor’s cows running for cover. And as we drove away, lightning continued to flash, but the rain never came.

Lise Olsen is a senior investigative reporter at the Houston Chronicle. The third installment of The Eleven, a five-part documentary series, airs Thursday, October 26, on A&E at 9 p.m. Central Time.