Hypnotic, the supernatural thriller starring Ben Affleck that opened on Friday, is Robert Rodriguez’s twenty-first movie. The lifelong Texan is more prolific than almost any of his ’90s indie-film contemporaries—Quentin Tarantino, whose Reservoir Dogs debuted about a year before Rodriguez’s El Mariachi, has only made ten!—and that’s including a five-year hiatus during which he ran his own cable network.

With such a body of work, it’s easy to identify certain elements that make a Robert Rodriguez movie. There’s often a lone avenging badass—El Mariachi, Machete, or Bruce Willis’s Detective Hartigan—wreaking havoc on a gloomy, noir-ish city (frequently in Mexico). There’s often a girl, or maybe a young woman, who’s talented on her own, important to our male protagonist, or both—see Alita: Battle Angel, From Dusk Till Dawn, Planet Terror, Sin City, and the Spy Kids franchise. The action will be exquisitely staged. Rodriguez will use a bunch of directorial tricks to make fifteen cents look like a dollar on screen. The music will be composed by someone whose last name is “Rodriguez,” the script won’t entirely hold together, and there’s a good chance Jeff Fahey will show up at some point. Given all that, Hypnotic is perhaps the most Robert Rodriguez movie of the filmmaker’s entire oeuvre.

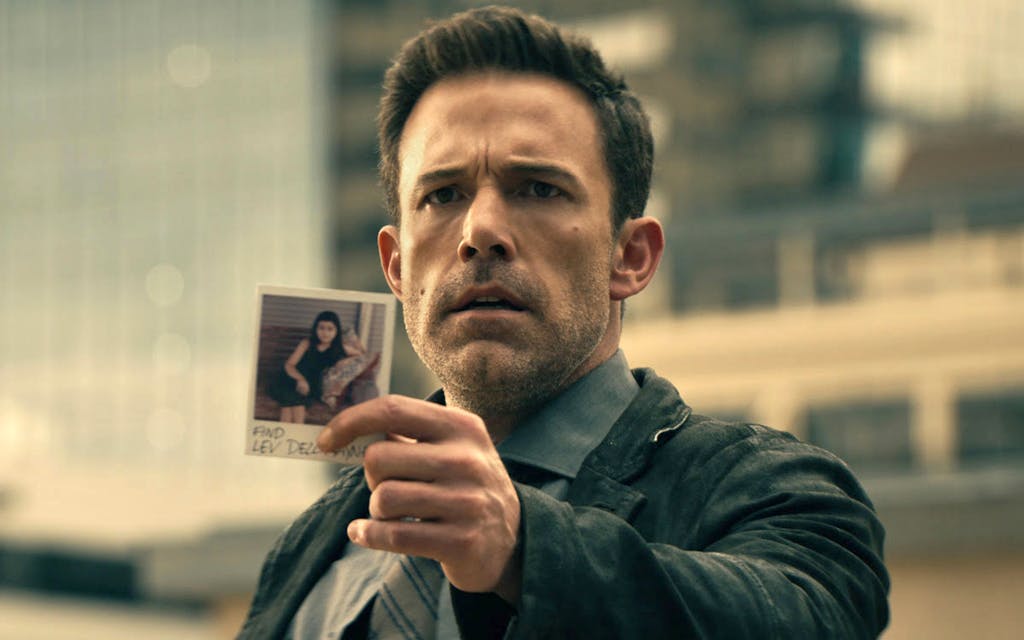

The film, which was both shot in Austin (another common attribute of Rodriguez’s work, given that his studio is just up the block from the Mueller H-E-B) and set in the city (a relative rarity), stars Ben Affleck—channeling the divorced-dad/smoking-outside-Dunkin’ energy that he’s offered the paparazzi in recent years to good effect—as a police detective searching for his lost daughter. As he attempts this task, he learns of the existence of a type of person called a “hypnotic,” who has mind-control powers that extend well beyond telepathy. These are folks born with the ability to turn friends into enemies, force four strangers to rob a bank, or, crucially, to turn a random person at a park into a kidnapper. As Affleck’s Detective Rourke realizes that the man responsible for his daughter’s kidnapping (William Fichtner as the villainous Dellrayne) was pulling the strings from afar, he finds an ally in another hypnotic, Diana (Alice Braga). The two end up seeking the government agency that works with hypnotics as part of a journey that takes him from Austin down to Mexico and back, with action set pieces that recall Christopher Nolan and twists that attempt to earn the film’s Hitchcockian title.

The film is also vintage Rodriguez in that many of its plot points seem downright convoluted. Dellrayne’s motive for the kidnapping is paper-thin, his plan to rob banks to steal from safety deposit boxes that he himself opened seems pointless, and all the American officials that Rourke and Diana need to find somehow live in the same city in Mexico. All of this makes little sense, but because of the twists in the film’s third act, Rodriguez recontextualizes what looks like sloppy storytelling into an integral part of the film’s narrative. This time, there’s a reason for all of those apparent plot holes—a classic bit of cinematic misdirection that makes Hypnotic more clever than the bad movie it appears to be for its first hour.

Finding ways to turn shortcomings into assets has always been one of Rodriguez’s defining features as a filmmaker. He shot El Mariachi on an initial budget of $7,000, so he made it look like he had access to crane shots by standing on a ladder, or like he had multiple cameras by filming snippets of the same scene from different angles. He helped pioneer digital filmmaking by building a huge green screen at his Troublemaker Studios to keep costs down. He gets access to bigger stars by offering them a chill, creative environment on sets that he often controls every detail of. (When actors aren’t filming, he sets up easels at the studio and offers the opportunity to paint, to keep the creativity flowing.)

With Hypnotic, he turns another one of his weaknesses into a strength. This time, it’s the fact that he’s often enamored of scenes and setpieces that don’t fit naturally into a cohesive narrative. There’s a reason Dellrayne is raiding those safety deposit boxes, and leading all of those cars outside the federal courthouse downtown to explode, even if it’s not clear at first (or second) glance. Turning narrative incoherence into a clue to the larger plot is the sort of creative problem-solving that made Rodriguez a star filmmaker in the first place, and audiences that don’t assume they’re smarter than the film will be rewarded for it. Hypnotic’s not a perfect movie, but it’s maybe the perfect example of a Robert Rodriguez movie—scrappy, weird, clever, with action sequences that are staged better than films with budgets three times its size. There’s a reason for his longevity as a filmmaker, and it’s on full display in Hypnotic.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Robert Rodriguez