Five years ago, a tour of Kieth Jackson’s properties wound through the plush lawns and gleaming houses off Texas Highway 6 in West Houston. From 1975 to 1980 Jackson sold up to two thousand lots each year, in his peak years doing $25 million in business.

Today on Kieth Jackson’s newest piece of real estate, two chickens pick at the dirt in a clearing in the middle of a steamy jungle. The whirr of cicadas drowns out the pounding of the Caribbean a thousand feet away. Inside an aluminum building are 43 sea-blue indoor swimming pools filled with salt water, larvae, and soybean meal. Jackson has been a rancher, an oilman, and a developer, but now he has seen the future, and it is a shrimp farm in Cucumber Beach, Belize.

“Business in Texas started to go to hell in a hand basket in 1980 and from there got progressively worse,” Jackson says. “In 1983 I said that’s as far as it goes. I got involved in Belize, and I’m concentrating down there until the market in Texas does something.”

The Belize of which Jackson speaks is nine thousand square miles, most of it covered by mahogany jungle, tucked under Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. Formerly a logging colony known as British Honduras, Belize gained its independence from the Crown in 1981 and has left many of the niceties of countryhood charmingly unfinished. Belize is now a country of rich agricultural land with an English-speaking, democratic government yearning for someone to do something to it. “They will develop laws to fit your problems,” says Jackson. “They want to do business. In Texas you have bureaucrats who don’t care if they do business with you or not.”

In Belize there are hardly any bureaucrats. There are also hardly any roads, hardly any bridges, and hardly any reasonably priced electricity. But that’s all right. An enterprising Texan with a modest bankroll can build a hydroelectric power station. At least Jackson says that’s what he intends to do. Jackson’s other plans for Belize since 1981—none of which has come to fruition—have included a water buffalo ranch, a vegetable farm, a soybean farm, a luxury hotel, an electric company (to be known as Belize Power and Light, which would own the planned hydroelectric plant), a retirement community, and a bank.

Jackson is one of several dozen Texans who have decided that Belize, a two-hour flight from Houston, offers what Texas had a long generation ago: wide-open opportunity, little government interference, and a good business climate. The Texans who bring their plans to Belize range from the scramblers trying to sell Belize’s slightly overeager government on their personal traveling circus to one of the most powerful businessmen in Houston, Allied Bancshares chairman Walter Mischer. Other Texans own hotels, vacation-home developments, adventure-travel businesses, mahogany forests, clothing-assembly plants, and land waiting to be turned into orange groves or cattle ranches. You want to make it in Texas today? Come to Belize.

The romance started in July 1970, when Jerry McDermott, then head of a six-man Houston energy investment company, came to Belize looking for oil. Instead he found Paradise. A friend took him to Ambergris Caye, an island twenty miles off the Belize mainland. McDermott fell in love with a piece of land in San Pedro, Ambergris’ tiny fishing village. He loved it so much that he bought it. “I was divorced, and my kids were grown,” he says. “The company had a series of dry holes and was in poor shape. I got out a bottle of Scotch. I said, ‘Have a drink, everyone—when this bottle’s gone, I’m gone.’ ” He went back to San Pedro with $10,000. “There was a small building that four nuns had lived in,” McDermott says. “They had found a piece of driftwood and painted ‘Paradise’ on it. The land was a swamp. I chopped mangrove trees and filled it with sand. I built buildings and seawall. There wasn’t any electricity. That building was the office, my house, the bar, and the rooms. I ran back and forth to Houston to get people to come here.”

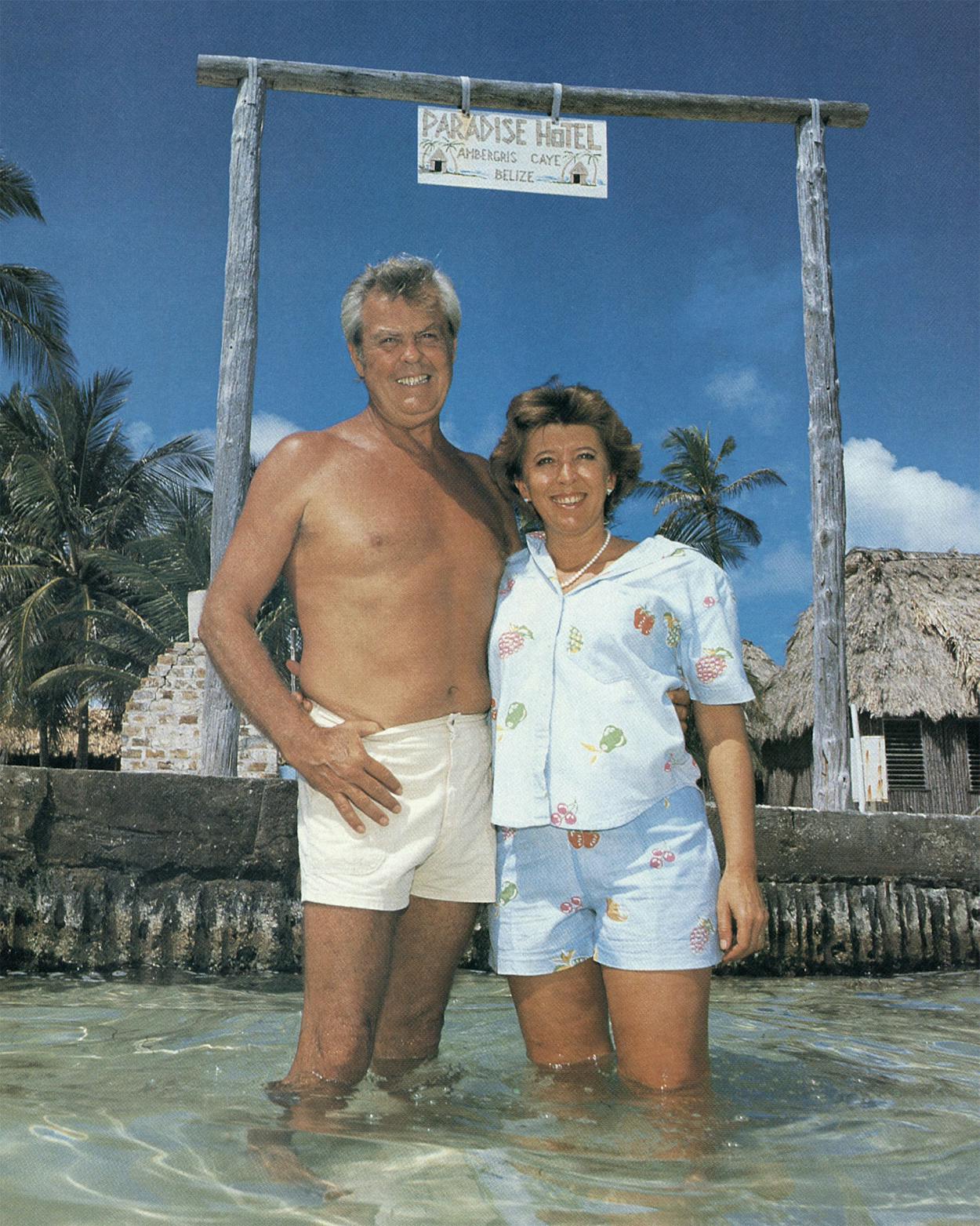

McDermott interrupts his story to go to the refrigerator in his luxurious wicker-and-wood-stuffed house and fix himself a drink. He is wearing his work clothes: a pair of white shorts. His house overlooks what Paradise has become: a $2 million hotel, offering thatched-roof cabanas, swimming, scuba diving, snorkeling and fishing trips, and arguably the best restaurant in Belize. “We’ve had Bobby Moody, Roy and Harry Cullen, Trammell Crow, and W. W. Caruth here,” he says, dropping some Texas names. “Eight out of the top forty on the Forbes 400 have been guests here.” As I sit talking to Linda, his wife, the crew of the television show Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous walk by—they are going to take actor Michael Paré scuba diving.

Some of the Texans who visited Ambergris Caye began to buy land themselves, and then as business in Texas worsened, they bought more than land. “You can’t spit out the window without hitting someone from Houston,” says American-born Emory King, a Belizean entrepreneur and the nation’s resident philosopher, who has been in Belize since 1953, when his planned world cruise ran aground on the reef. Among those within spitting distance are A. W. Dugan, a Houston petroleum investor with plans to develop a 250-lot vacation-home subdivision to be called Club Caribbean. A group of Texans that includes Houstonians Browne Rice, Flavy Davis, and Ab Fay own another luxury hotel on Ambergris Caye, the Victoria House. “I go wearing shorts to see my banker,” Fay says. He recalls of the hotel’s construction in 1980, “We brought the sand and gravel from Belize City on sailboats. Then we ran out of nails. There were no nails on Ambergris. We went to Belize City. There were no nails in Belize City.”

A little thing like a whole country running out of nails might discourage other investors, but Texans seem to lap it up. The Texans in Belize love to tell stories about its frontier-town qualities and the government’s wild infatuation with foreign investment. You can buy Belizean citizenship for a $12,500 application fee and a government-approved investment plan, and foreign businesses routinely receive tax holidays and ten-year duty-free importation of goods. The country of Belize offers the nostalgic Texan not only the perfect business climate but also the perfect climate, period. Coming to Belize has less in common with taming the West than with being one of the first settlers in St.-Tropez.

Belizean businessmen and government officials have taken frequent trips north to seek Houston investment. Two months after his election in November 1984, Manuel Esquivel, the conservative prime minister, and several government and business leaders flew to Houston in Kieth Jackson’s Learjet. They met Mayor Kathy Whitmire, her erstwhile opponent Louie Welch, businessmen, and convention promoters, movie promoters, and tourism promoters. The tour guides, says Belize Chamber of Commerce president Kent McField, were Walter Mischer and his frequent associate, Houston investor Paul Howell.

Mischer and Howell, who declined to be interviewed, had come to Belize in November 1984 to attend opening ceremonies for Jackson’s shrimp farm, in which they are part owners. Malcolm Barnebey, who was then the U.S. ambassador and is now a consultant to Mischer and Howell, introduced them to many of the Belizean leaders whom they ended up hosting in Houston. By the spring of 1985, says Barnebey, the two men were considering an investment. In October the partnership they led bought one eighth of Belize.

What the partnership bought was a 700,000-acre piece of jungle in northwestern Belize. Thirty per cent of the parcel went to Houston-based Coca-Cola Foods, which plans to grow oranges for its Minute Maid orange juice brand, and 40 per cent will be retained by Barry Bowen, who is the most powerful businessman in Belize. Mischer and Howell will own the remaining 30 per cent of the land package.

Operating on a somewhat smaller scale at his shrimp farm, known as Maya Mariculture, is Kieth Jackson. To him, Belize’s lack of infrastructure is an invitation to come build one. “It’s totally, completely undeveloped,” he says, with a booming laugh and his belly jiggling. “With Texas cash and Texas ideas, you could do something.”

When Jackson gets to talking about the future, his words sound uncannily like those that people once used about Texas. “Anything you can think of can be promulgated in Belize,” says Jackson. “Real estate, any kind of business. There’s plenty of cheap labor, no taxes, no labor unions. If I were head of Chrysler, I’d build a major assembly plant down there. But if you’re going to be an ugly American, stay home. They want partners—if you’re going to go and run over people, stay home.”

Emory King says that Jackson once told guests at a Belize dinner party, “Like it or not, you all are going to become Texanized.” Not all Belizeans welcome such an occurrence, however. Many are suspicious, precisely because the same atmosphere of Texas-size possibility that attracts Jackson has brought others to Belize before.

“Belize is a mirage,” says King. “This is one of the last places in the world for crazy ideas. We’re a tolerant society; we just nod and say yes. They get off the airplane here, and they say, ‘Good God, these people are all asleep! I can do anything here—make a million dollars.’ Nobody disabuses them, but they find out eventually you can’t make a million dollars.”

“Any idea to make money has been tried here in Belize,” says the commercial attaché at the American Embassy. He adds that between 25 and 30 per cent of his visitors are Texans asking advice on a project. “You get lots of smooth talkers, especially from Texas,” says chamber president McField. “We had one man who asked for a fuel import exemption for more fuel than would generate energy for Belize for a year.” He shrugs; this, after all, is Belize. “You get all kinds of con men when you need investors so much.”

Tina Rosenberg is a freelance writer based in Latin America.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics