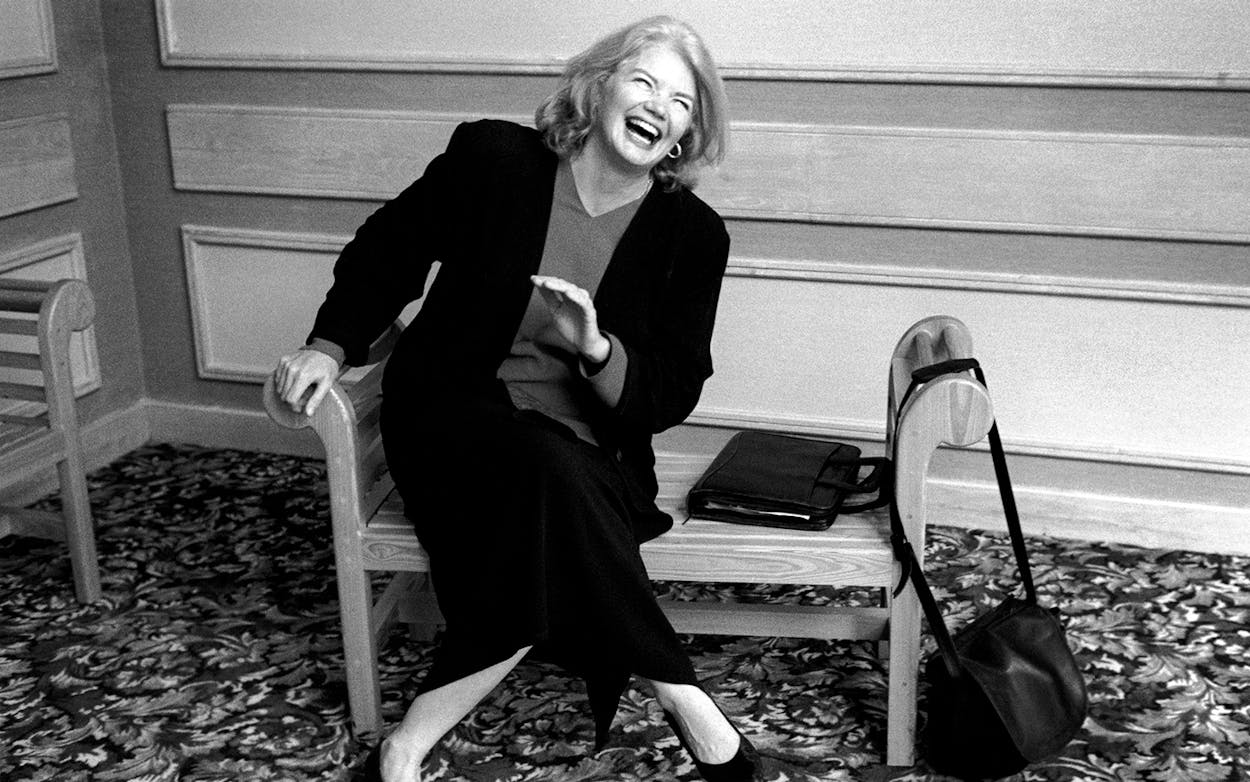

Perhaps better than anyone, political commentator and journalist Molly Ivins could describe the absurdity of Texas and its politics with unabashed candor.

“There are two kinds of humor,” she said in a 1991 People magazine story. “One kind that makes us chuckle about our foibles and our shared humanity…the other kind holds people up to public contempt and ridicule—that’s what I do.”

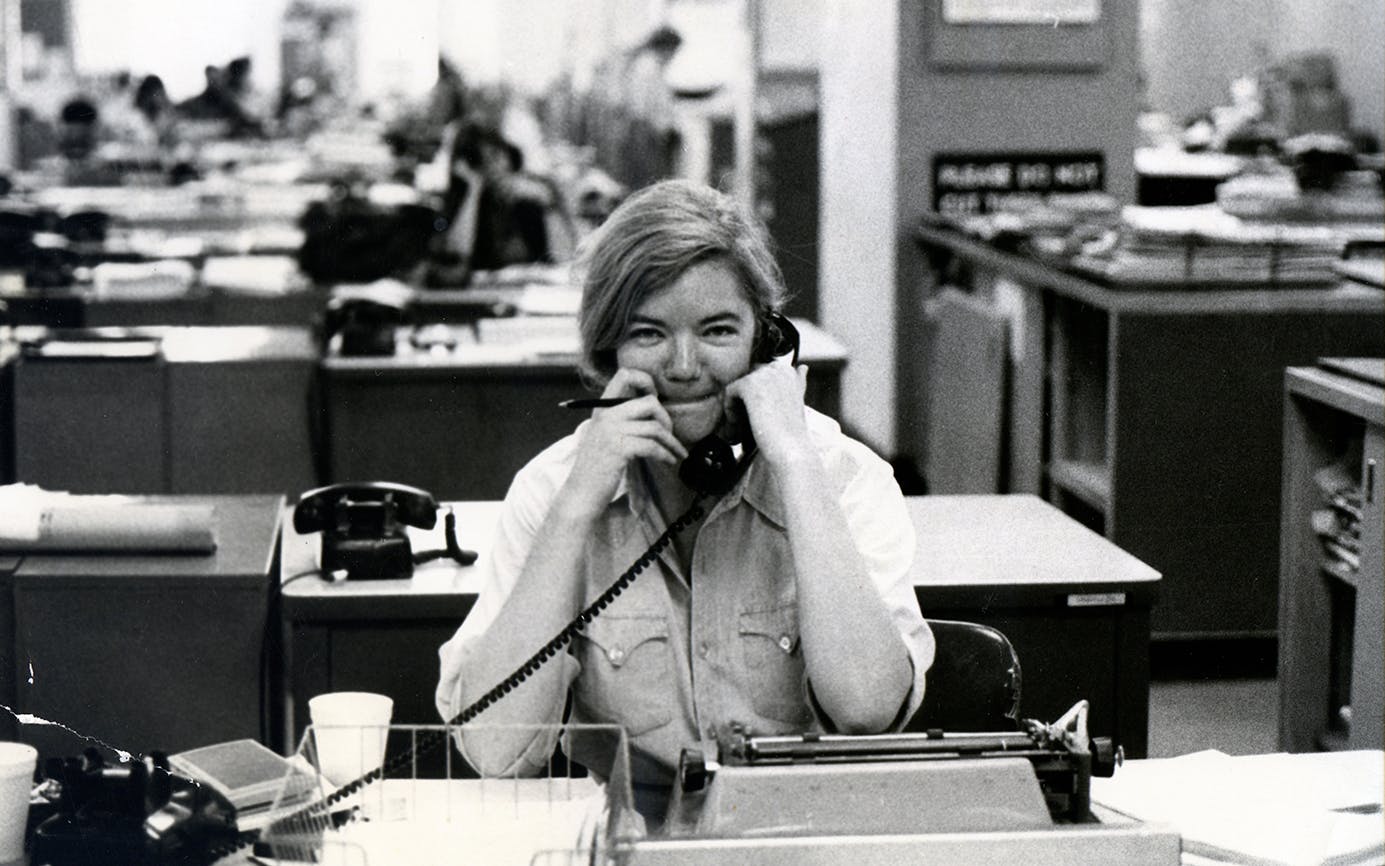

Ivins, who grew up in a conservative household in Houston, is best known for her work in the Texas Observer and as a columnist at the Dallas Times Herald and Fort Worth Star-Telegram. The response to her column, which was eventually syndicated in hundreds of newspapers nationwide, prompted a billboard ad that read, ”Molly Ivins Can’t Say That, Can She?”

Ivins died in 2007 after a battle with breast cancer. Now a new documentary is introducing Ivins to a whole new generation. Raise Hell: The Life and Times of Molly Ivins, which premiered at January’s Sundance Film Festival and played South by Southwest in March, is getting a theatrical release beginning August 30. We spoke to the film’s director, Janice Engel, about Ivins’s fierce spirit and the lessons today’s young people can take from her legacy about taking political action.

Texas Monthly: What drew you to Molly Ivins and creating this documentary?

Janice Engel: I went to see the play Red Hot Patriot: The Kick-Ass Wit of Molly Ivins in 2012 at the behest of my dear friend, James Egan, who wanted to make a film with me. I was blown away by the material. I did not grow up with Molly Ivins. I grew up in New York and then came to California to go to college, so I wasn’t part of her constituency. I knew of her. I think I’d seen her on Letterman in the ‘90s, and I knew that she had dubbed George W. Bush “shrub,” which I thought was very funny.

But I didn’t really know about her. So this was really my introduction to her, seeing the play. I came home, and rather than going to sleep, I went to Google. I Googled until two or three in the morning and watched Molly on C-SPAN and a variety of stuff. I just said, “Oh my god, she’s a laugh a minute, and she’s brilliant.”

Just six weeks later, I was on a plane to Texas, and then we kicked it off with our first six interviews.

TM: What went into making the documentary? What was the process?

JE: The process took six and a half years. It’s a deep archaeological dive when you go into doing a documentary on somebody and their life. The good news was that her papers were housed at the Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas in Austin. Her archive is tremendous. I lived there [in Austin] for different periods of time in 2013, 2015, and 2016. Then I hired a boots-on-the-ground researcher to do some digging with me, and the goal was to find as much information to read about and to find those nuggets and also artifacts that I could put in the film.

The good thing about Molly is she saved everything. Somebody once said that she knew she was going to be famous. In fact, I found notes that her father had left her on the kitchen counter from her teenage years [and] all her letters home from camp, which is where I discovered that she was actually quite funny. She was really a riot as a kid. I found the [pictures] you take in photo booths with your best friend. Lots of little artifacts and things.

We did 45 interviews. Of course, not everybody made the cut.

TM: How did Molly’s conservative upbringing shape her voice?

JE: I think that was a major part of what motivated her outspokenness. I mean, Molly spoke truth to power. Well, who was the power in her growing up? It was her father, who was the patriarch of the household: white male privilege, corporate titan, a lawyer. She called him the General. That totally set up a pattern for the rest of her life.

TM: She also entered journalism at a time when there weren’t many female journalists. How did that influence what she wrote about and how she wrote about it?

TM: She also entered journalism at a time when there weren’t many female journalists. How did that influence what she wrote about and how she wrote about it?

JE: The only way she could really be a journalist was you had to have an extra edge. You had to have a master’s degree. That’s why she got it. She went to Columbia j-school. Women were relegated to fashion, gardening, and lifestyle back then.

TM: Why do you think that her voice as a political commentator resonated with so many people?

JE: Because she speaks truth. Because she pointed out the obvious. Because she had courage. People need somebody to stand up for them. And basically Molly was a tall glass of water in a parched desert of people surrounded by very conservative and fearful viewpoints, and she made people feel like they weren’t crazy, that they’re not living among extremists and alone. She gave voice to those feelings, especially in places where it wasn’t popular, and I think that was incredibly, incredibly important.

I want to address something you asked me in your last question about coming up at a time when the guys were in charge. That’s still going on today. It hasn’t changed. The door is open, but it’s ajar. And unless you and I, and all us gals coming up and people of color, shoot off the hinges and rebuild it, it ain’t gonna change. I work in the film business. Let me tell you, it is so regressive and backwards in many ways.

TM: Molly believed that there’s no such thing as objectivity. That notion of objectivity is still a major tenet in journalism, despite a debate about what that means. How do you think that affects truth-telling in media?

Engel: What’s happened in media—this has been going on since the Reagan era—is the siloing. There’s all these silos, and it’s an echo chamber. And that is because of corporate media. I think that what we’re seeing is that you have to protect the Fourth Estate. We have to protect independent voices. In respect to Molly, it’s absolutely important to speak truth to power. It’s absolutely important as a journalist, and a person who is working in the media, to be as respectful and on target about the truth.

TM: The documentary also talks about her struggles with alcoholism and breast cancer, and she seemed to retain her sense of humor throughout it all.

Engel: Humor was her salve. Humor was also her armor. Humor would deflect. [Writer] Anne Lamott, who’s in the film, said Molly was the most courageous person she’s ever known because she was willing to speak up when it was very, very scary to be unpatriotic at the start of the Iraq War. Molly Ivins spoke out when nobody else would. But Molly Ivins, who can speak truth to power to anyone, was a hardcore alcoholic and didn’t really want to face her own truth for years. She went to “drunk school”—she used to call it “drunk school.” She would go dry out, she would clean up. She would stop smoking, she would lose weight. And she had been diagnosed with breast cancer.

In the middle of it, she told her friends, “What, quit drinking and smoking? The only two things that I love? Are you nuts?” Right after getting sober, she found out she was really dying. Now most people would have said, F— it, I’m going out in the blaze of glory. But Molly Ivins decided to stick to her sobriety. She wanted to go out clear-headed. She actually did the most courageous act, that’s what Anne Lamott said. She faced her own truth, which is very hard to do, especially when you know you’re dying. That’s tremendously courageous.

TM: What do you think Molly’s legacy is?

Engel: Molly’s legacy is that it’s up to us to do the heavy lifting. Her legacy is: Take responsibility. Vote. Don’t sit on the sidelines. Her legacy is also kindness, acceptance of people who are other, who are different from you. Always remember to have fun and laugh. Have a good time while you’re fighting for freedom. [Her longtime friend and author and activist] Jim Hightower said, Molly knew that humor was the door key to the brain. You’ve got to unlock that little door to get people to finally listen to you. So humor was a great way in. What she’s telling us is laugh, have fun, talk to your neighbor who disagrees with you. You’re going to find there is common ground.

TM: Can you talk about the relevance of her work and ideas in today’s era of politics and news?

Engel: Molly was incredibly prescient, so what she wrote or talked about fifteen, twenty, thirty years ago is happening right now. The thing is that history is cyclical. I’ve said this, and I’ve gotten flack for it—that she’s more relevant now than when she was alive. No, she was incredibly relevant when she was alive, but shit’s so much worse right now. I believe she would agree, which only means listen to her. Take responsibility. Talk to those that disagree with you. Vote.

I have a Holocaust education program called What We Carry. And one of the greatest quotes I ever heard was one of my Holocaust survivors, at 94 years old, may he rest in peace, said, “Evil does not need your help, just your indifference.”

Raise Hell will be playing in select Texas theatres starting August 30. For more information, visit mollyivinsfilm.com. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Documentary

- Molly Ivins