One night back in 2000, a friend at my weekly poker game of Austin music-scene veterans announced that, according to a guy he knew in Houston, young people in the hip-hop scene were basically going insane. They were slowing down their music so it sounded like the tape machine was running out of batteries, drinking codeine cough syrup, and driving around town listening to the music as loud as their speakers would go. “No way,” we all said. The leader of this musical movement was a young man who went by the name DJ Screw, and he was some kind of local legend. All we knew was, there was nothing like that happening in Austin—supposedly the music capital of Texas.

A month later, Screw, 29, died from a codeine overdose. By chance, I saw his obituary in the Austin paper—Robert Earl Davis Jr. had been raised in nearby Smithville, and he was going to be buried there that weekend. I went to the funeral, met some of his family, and began a journey into a whole other world.

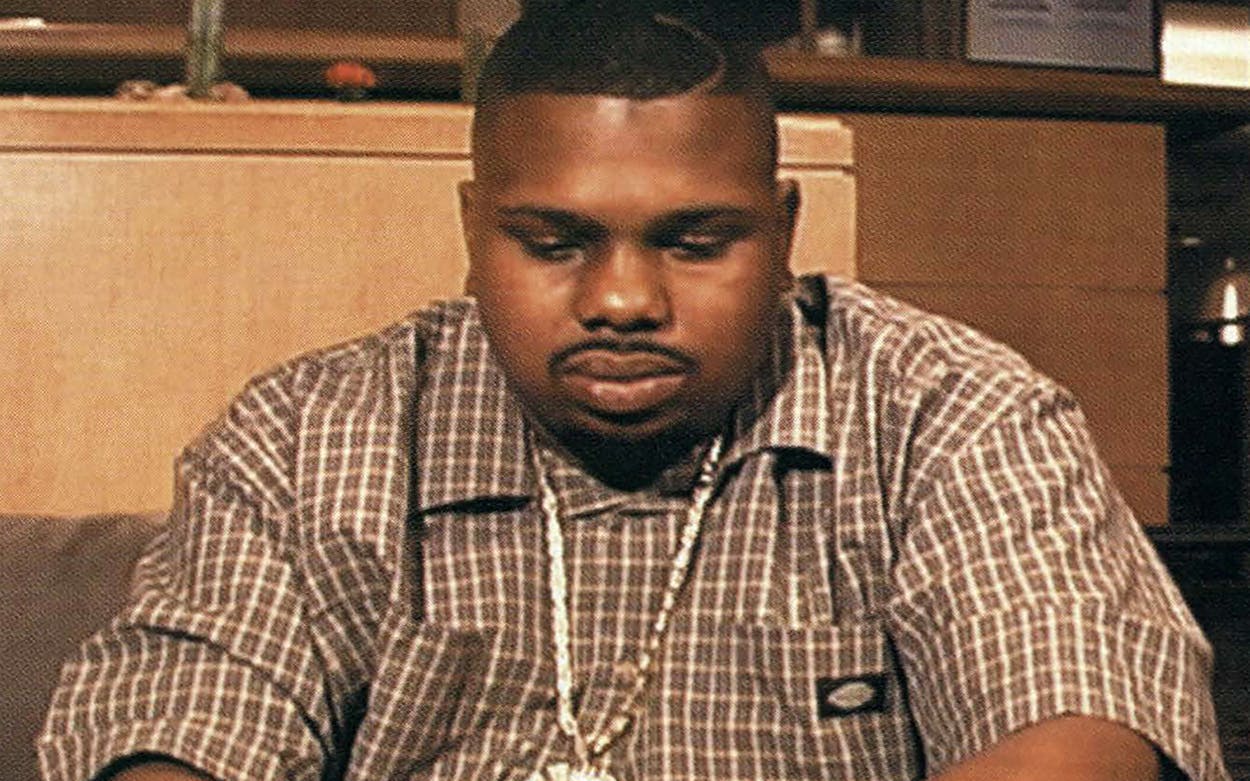

Over the next six weeks, I took four trips to Houston, and each time I visited, I fell deeper into the scene there, meeting rappers who had worked with Screw, store owners who sold his tapes and CDs, friends who knew him. Screw had basically built an entire music scene around his homemade tapes, on which he’d take other peoples’ beats, rap over them, get his friends and up-and-coming MCs to rap too, and then slow the whole thing down—“screw” it.

“Screw had found a way to slow down time,” I wrote in “The Slow Life and Fast Death of DJ Screw.” “He had found another world.” He’d sell the tapes out of his house, and they got so popular cars would line up down the block. His rap friends became stars—and made more albums for other labels. The scene exploded.

By the end of my reporting, I was scoring codeine at a midnight buy with a couple of new friends in a part of town I would never have visited otherwise. Then we went to a recording session—and I was entranced. The drugs made the music . . . deeper, richer, more fun, just like drugs have done with other kinds of music, from psychedelia to jazz.

We published the story in early 2001. In the years since, Screw’s legacy grew. Screwed music spawned subgenres like lo-fi hip-hop and slowed and reverb. Everyone from Frank Ocean to Beyoncé released screwed songs and albums. In 2021, Screw crossed further into the mainstream with the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston’s exhibition highlighting his impact and a season of the Gimlet Media podcast series Mogul looking back on his life and career. A year later, UT Press released a biography. The underground rap superstar—the high school dropout from Smithville, Texas—had become a full-blown music icon.

Over the years I’ve received numerous emails in response to this story, often from people who had been as dumbstruck as I was when they first heard about what Screw was doing. No way, they’d thought. Then they listened.