With a TV miniseries on the way and the enduring popularity of his chopped-and-screwed production style, Houston’s DJ Screw remains a vital cultural figure 22 years after his death. Now a new book—part oral history, part cultural criticism—is set to spread his legacy even further.

Lance Scott Walker’s DJ Screw: A Life in Slow Revolution tells the story of Robert Earl Davis Jr. from the beginning, when Davis was a kid running around the small town of Smithville (in Bastrop County), through his heyday on Houston’s south side and the end, in 2000, when he died at age 29 as an underground legend in his adopted home city. In between, he taught hip-hop heads the glory of slowing things down with a series of mixtapes that became hot commodities on the south side streets and beyond.

The Galveston-born author, whose previous books include the excellent Houston Rap Tapes, remembers first hearing Screw when he moved to Houston in 1992. “The Geto Boys were local heroes, breaking nationally the summer before,” he writes. “Shortly thereafter, it was DJ Screw who would emerge to define the sound of the city. You heard it first in the streets, and it was heavy. It was enchanting. It was mystical. It made Houston feel different from anywhere else on the planet.”

As Walker points out, Screw wasn’t the first to slow down records. DJs in Miami and Mexico slowed and extended sound as early as the seventies, and Screw’s friend Darryl Scott was already doing it in Houston. But Screw made it an art form and a signature. He learned to manipulate pitch control like a master, slowing down his tape decks and using his fingers to drag against the wheel of the turntable. Others were doing variations on these techniques, but none took it as far, or did it as well, as Screw.

The book keeps its ear to the street through extensive interviews with Screw’s friends and colleagues, people like Big Bubb, Shorty Mac, and Screw’s fellow Screwed Up click members Lil’ Keke and E.S.G. Like most of Walker’s work, DJ Screw is notable for its thorough reporting. Walker isn’t breaking any news here, at least not for those who know the Screw story (though, to be fair, many still do not). But the touches of oral history bring the story down to ground level and allow those who knew Screw to describe him in their own voices. A biographer can say something like, “Screw had trouble concentrating in class.” Here, we have Screw’s old friend Al-D say, “We kept gettin’ kicked out the f—n’ class because I had him laughin’ in the class. I was drawing pictures of my cousin and s—, and man, Screw wouldn’t shut up because I was crackin’ jokes and he was tryin’ to hold his breath.” Walker chose option B, and especially in describing life in a city as culturally rich as Houston, he made the right call.

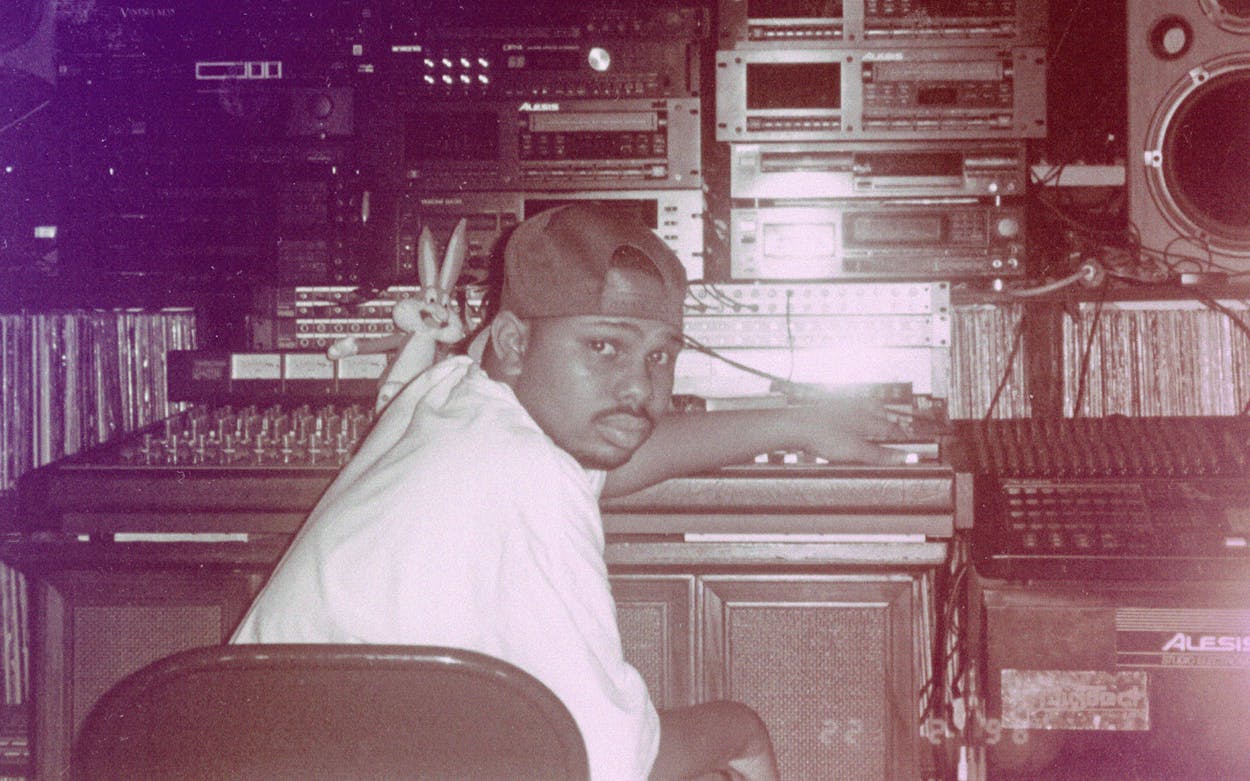

In one scene, Walker takes us into Screw’s home as the maestro went to work, passing a microphone around the room, his friends taking turns rhyming all night long. They could only imagine what the end result would sound like. “Everyone’s perception of what a Screw tape sounded like when they recorded it live at his house was one thing, but they were made to believe in his touch when they finally heard Screw slow it down to where he was hearing it in his head.” Then there was the editing process—the chopping—which involved “deconstructing a song’s relationship with its lyrics, shaking the linear story within, all the while cutting new rhythms into the cloth of the sound.” The book charts Screw’s rise as a folk hero around town who was known for his affable demeanor and entrepreneurial spirit. He was the young man with the mixtapes everyone wanted, an archetype of the hustler selling music out of the trunk of his car.

It remains eerily difficult to separate DJ Screw’s sound from his death by overdose, after which coroners found codeine, Valium and PCP in his blood. Lean, the concoction that mixes codeine cough syrup with soda (and Jolly Ranchers, if that’s your thing) over ice, predated Screw on the Southside by many years, and Screw was slowing down records well before he became a dedicated lean drinker. Rappers shouted out lean on Screw mixes, which often seem to slow everything down in an aural haze. Though codeine wasn’t the only drug found in Screw’s system when he died, it will always be connected to the chopped and screwed effect. As Walker writes, “Whatever part recreational cough syrup played in Screw’s life, his was the first high-profile death associated with its consumption, and thus from the moment his coffin closed began an uphill battle to separate his legacy from it.” One might ask if that separation is even possible, though Walker certainly tries his damndest. Yes, there was far more to Screw than his death and its cause. But his death and his music will always be inextricably linked. Walker soft-pedals this connection a bit, even as he covers the death in detail.

Still, it’s impossible to overstate Screw’s impact on the city he called home. As Walker writes, “His work is an audio map of the southside of Houston, Texas.” And this book is a worthy topography of Screw’s life, from its humble start to its tragic end.