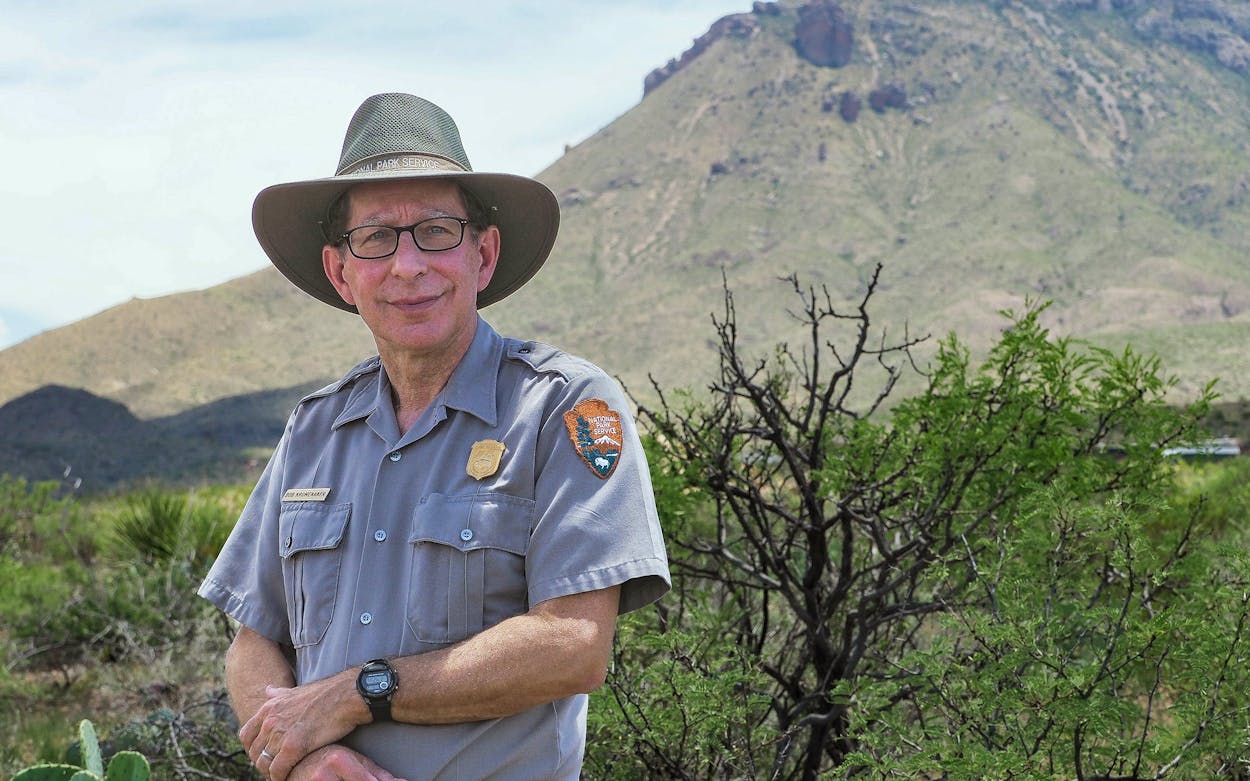

Bob Krumenaker swapped the windswept waters of Wisconsin’s Apostle Islands for sun-baked West Texas nearly five years ago, when he became superintendent of Big Bend National Park. When he reported for duty at the prickly and remote 801,163-acre park along the Rio Grande—where visitors come to hike, camp, and observe black bears, tarantulas, and javelinas—Krumenaker quickly learned to plan ahead. After all, the nearest grocery store is close to a hundred miles away.

Then came a barrage of challenges. In December 2018, three months after he started, the federal government shut down. A few months later, a wildfire gutted the barracks building in the park’s historic Castolon district. That was all before the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to an unprecedented surge in visitors to the park, and another fire that scorched about 1,300 acres high in the Chisos Mountains.

Krumenaker, 66, will retire from the National Park Service in July. He leaves behind a park that’s working to accommodate all the crowds and is ramping up for some major infrastructure renovations.

The park veteran and biologist started as a volunteer at Canyonlands National Park, in Utah, 46 years ago, surveying fence lines and patrolling trails. Before moving to West Texas, he worked at Isle Royale National Park, Big Thicket National Preserve, Shenandoah National Park, Valley Forge National Historical Park, and Apostle Islands National Lakeshore, where he spent sixteen years before coming to Big Bend. “This park has been spectacular and all-consuming, and I’ve loved it,” says Krumenaker, who plans to move to Carlsbad, New Mexico, when he wraps up work here. Though he’s leaving the park, he says he’ll continue to work with the advocacy group Keep Big Bend Wild toward another goal: to see Big Bend National Park permanently protected as a federally designated wilderness area. “It’s not even close to being done, and I’ll continue to work on that as a volunteer,” he says.

We sat down at a picnic table outside his office at Panther Junction, surrounded by a desert wearing an unusually lush coat of green thanks to recent rains, to talk about his time at the park and what comes next.

Texas Monthly: Why did you decide to retire?

Bob Krumenaker: I’m ready to do something different, and I want to be with my significant other all the time. And I think the park is in good shape. I’ve officially done forty-one years [as a full-time National Park Service employee] and I don’t want to do this when I’m seventy. I’m not eager to give up some of the cool things I get to do as superintendent, though, so it’s a little bittersweet.

TM: What’s the biggest challenge facing Big Bend National Park?

BK: The ability to meet the public’s expectations with the resources we have available. That gap is growing wider. We love that more and more people have discovered Big Bend and want to visit, but the park’s physical capacity is limited, the maintenance backlog is growing, and our ability to recruit people to address those issues is going in the wrong direction. We have a lot of vacant jobs that we can’t fill because we don’t have the money, we don’t have good candidates, or we don’t have housing for them.

TM: What about the health of the National Park Service as a whole?

BK: I would say there’s a tremendous disconnect between the expectations of the American public, and what they want and expect, and the National Park Service’s ability to do those things based on the availability of funding and their ability to recruit and maintain staff in places like Big Bend. The debt-ceiling agreement that just passed calls for an essentially flat budget over the next two years, and a flat budget is effectively a declining budget. That’s not news, but it makes it difficult to dig out of holes.

TM: You had to deal with a government shutdown early on. What did you learn from that?

BK: Three months after I got here, we went through a 35-day shutdown. That was tough on staff, but a huge opportunity to take ownership of my responsibilities and recognize that looking out for staff and focusing on quality of living and working here was important. We can only manage the park well if we have great people working here, and there’s a lot more to be done.

TM: How did you manage the pandemic?

BK: I made the controversial decision to close the park in 2020 for about six weeks [in two segments] to protect people. Were those the right decisions? They were the right decisions based on the information we had at the time. Until there were other COVID variants, we had one-twentieth the number of cases in the park as the county and state had, and that’s not a coincidence.

TM: The South Rim fire, which burned more than 1,300 acres in April 2021, was the first big fire in the Chisos Mountains in the park’s history. What are the takeaways from that?

BK: The South Rim fire was very scary because there are a lot of sensitive natural resources up there. Our general impression is that even though it was a human-caused fire, it was generally pretty good for the ecosystem, although the impact scars will be visible for the rest of our lives.

There was a legitimate worry the fire would tumble off-mountain and impact developed areas. It did not do that, thanks to efforts of firefighters. We learned a lot about how to protect the basin, and we’ve done a lot of work to clear vegetation away from burnable buildings. Our buildings are less vulnerable to fire than they were before.

TM: One of your goals was to make the park more energy-efficient and sustainable. How much progress did you make?

BK: There has been a lot of ground to make up, but I think we’ve succeeded in changing the way we look at energy and water usage. We just put in a solar array that will power the visitors center at Panther Junction. We’re also working on a conceptual plan for powering all of Panther Junction with solar energy and battery backup to address the frequent power outages that are health, safety, and morale issues here.

TM: You said when you started that some facilities in the Chisos Basin were falling into disrepair. What’s the status of the $22 million project to replace the main lodge building?

BK: The whole complex—the check-in area for the lodge, the restaurant, administration offices, bathrooms, loading dock, and storage building—will be demolished, along with the camp store next to the visitors center. [Closure of the existing lodge has been delayed until October 2024.]

The structure that arises from the footprint will include retail on the first floor, and a larger restaurant on the second floor, so we can have outdoor dining without issues with bears. The new building will blend in far better than the existing building. It’s designed to fit the site, with neutral colors and large open spaces. I think people will like it. It will honor the old building, but not look like the old building. We have no plan to replace or add rooms. We don’t think that makes sense from energy-sustainability purposes, and there’s no room for parking more cars.

TM: How long will the revamp take?

BK: About eighteen to twenty-four months. We do think it’s going to be a major impact on visitors, so we’re gearing up for that. The good news is I think it will generate use of other parts of the park, and there are benefits to that. Tactical decisions will be made by my successor. But the reality is it’s going to be difficult to maintain hotel operations, because they’ll be replacing underground water lines. Trails will remain open, but visitors will have to access them through the campground. There really is no way to maintain service in the dining room. It’s our intent to provide some kind of food service elsewhere in the park—that could be food trucks or a temporary kitchen out of a trailer.

TM: How do you deal with all the trash the park generates?

BK: We are one of only two national parks that still operate in-park landfills. That’s not compatible with our mission. We have a few years left in our landfill, which is located off Grapevine Hills Road. We’re trying to extend the life of it by improving compaction and how we manage trash, and we’ve ramped up our recycling program with help from the Big Bend Conservancy.

Our major emphasis is to significantly reduce the amount of solid waste we handle and find long-term alternatives. We’re working on that, but haven’t solved it. We’ve labeled our bins more clearly, and we would like more people to understand that the cities they come from are more able to handle solid waste.

TM: What will you miss most about Big Bend?

BK: Every single day I walk to work, and I get to breathe the air and look at the view of one of the most magnificent places on the planet. I’ve really tried of late to savor those moments.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

- More About:

- Big Bend