Many are the works of Pompeo Coppini.

Years ago, when “sculpture” was still largely understood to mean statues, Coppini was one of the most celebrated men in Texas. Major commissions came his way almost as a matter of course, enabling him to build a mansion in San Antonio’s Alamo Heights whose exterior he garnished with sculptural friezes representing various sublime ideals. Banquets were held for him, medals were struck, even a musical composition, “The Coppini March,” was written in his honor.

“Coppini, hail! a hero thou!” exclaimed Texarkana poet Mrs. J. B. Vaughan. “Time withers not these immortelles/Nor dims a name like thine.”

Mrs. Vaughan, who wrote those lines in 1916, turned out to be only half right. Few people today would recognize the name of Pompeo Coppini. His work has outlived his reputation—a common enough fate of sculptors who choose to express themselves in imperishable materials. But those works, those “immortelles,” are with us in abundance. His most ambitious sculptures—the Alamo Cenotaph and the Littlefield Fountain at the University of Texas—can rightfully be thought of as landmarks, and the rest of his oeuvre is liberally scattered throughout the state. In front of state buildings, on college campuses, in parks, town squares, cathedrals, and cemeteries, Coppini’s monuments stand with curious anonymity. They are, essentially, forgotten. Hardly anyone notices them or pauses to consider the massive physical effort and unblinking self-confidence that were needed to create them.

Coppini made his reputation in an age when a sculptor was judged on his ability to render an acceptable likeness of a civic leader or mythic hero, or to express some ennobling sentiment in bronze. Without question, he had the brute talent necessary to succeed. In terms of the human form, Coppini was a strict constructionist, and his best figures have a vigorous, literal quality that can be striking. In matters of technique, he was appealingly businesslike, but otherwise he breathed the thin air of artistic piety. He believed that only the loftiest principles were worthy of expression. To our modern eyes the very sincerity of his work is retrograde. His great bronze statues of forgotten philanthropists, martyrs, and allegorical figures seem, more often than not, simply wan. They are the work of someone who wants to uplift the spirit without disturbing the perceptions.

“Any individual who dares to call himself an artist,” Coppini wrote, “but who uses a graphic method of distorting, elongating, dissecting or disfiguring God’s given body, has in himself the same lurid joy and satisfaction as a criminal sadist gets in torturing and dismembering animals or human life.” Coppini did not go on to mention any criminal sadists by name, but doubtless he had xseen the work of Picasso and Henry Moore and other contemporaries who were wreaking havoc upon what he never ceased to call Fine Art. Coppini had the misfortune to behold the moment when it was no longer enough for a sculptor to be high-minded and workmanlike. The “so-called modern artists” were taking sculpture down a path from which it would never return, where artists like Pompeo Coppini could never follow.

HE HAD THE LOOKS OF A SCULPTOR: wavy hair, square frame, a tendency toward portliness. He posed for photographs with his thumbs hooked into the watch pockets of his vest and a sensuous, cocksure expression on his face. A man whose life’s goal is to build heroic-scale statues is not likely to have an insignificant ego, and Coppini’s sense of his own destiny was formidable. He had been put on the earth, he believed, “to follow the steep heights to glory.” That ascent began in a small village in northern Italy, where Coppini was born in 1870. His father was a frustrated musician, born into a wealthy merchant family whose finances were in ruins by the time he came of age. Suddenly thrust into the working class, he made every effort to ensure that his son chose a stable and remunerative career. But Pompeo had come into the world sprinkled with pixie dust, and there was no way this dreamy, passionate boy was going to become an engineer.

“There never was a really happy day in my home,” Coppini writes in his autobiography, From Dawn to Sunset. His mother was afflicted by “that green-eyed monster, jealousy,” and she made life miserable in the Coppini home with the constant accusations of infidelity that she directed against her husband. In that environment, with its domestic tension and its active denial of his need for artistic expression, Pompeo developed into an unruly and violent child and was expelled from nearly every school he attended.

It was in Florence, where his family moved soon after he was born, that the young Coppini found his calling. At the age of ten, he was hired to make little ceramic whistles shaped like horses that sold for a centime apiece. Later he worked in the studio of a sculptor who specialized in carving cheap replicas of famous Florentine pieces to sell to tourists. In that city, where the works of Cellini and Michelangelo were readily available as inspiration, Coppini became more and more determined to live the life of a sculptor, but it was only after he ran away from home at the age of sixteen that his father relented and allowed him to enter the Academy of Fine Arts. In his element at last, Coppini stayed long enough to earn a quick degree and then, with an audacity that would prove typical, rushed out into the world as Pompeo Coppini, Sculptor. He lost no time in opening a studio, where he specialized in making busts—at no charge—of local celebrities, hoping in that way to draw attention to his work. Ultimately the studio failed, but it was a shrewd idea, an early indication of Coppini’s understanding that his clients would forever be the rich and powerful. As a young sculptor, he had two great advantages: he knew his market, and he worked fast. He once astounded a client who was sitting for a portrait by modeling his bust in clay in less than an hour.

After he closed his studio, Coppini went to work for a sculptor who designed cemetery monuments, and he quickly fell into a rather cold-blooded courtship of the boss’s daughter. “While I found her not to be too bright,” Coppini admits, “I gave myself to thinking that it would be a good thing for me to marry her and become the business partner of her father.”

But the girl’s mother refused to give her consent, initiating a spate of ill will that climaxed in the local priest’s denouncing Coppini from the pulpit. At that point the temperamental young sculptor decided that it might be easier to ascend the steep heights to glory on the other side of the Atlantic. Thus it happened that in March 1896, with $40 in his pocket and “a trunk of very good clothes,” Pompeo Coppini, Sculptor, arrived in New York.

America in 1896 was smitten with the high old style of art. Only three years before, the great World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago had showcased on a gargantuan scale the prevailing sculptural ethic, which went by the name of “Moral Earnestness.” At its best, in the works of sculptors like Daniel Chester French and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, this style had a resonant naturalism, a plain strength that was so untainted by irony and ambiguity that it did in fact seem moral. But not every artist could hold such uplifting sentiments in check, and as often as not, moral earnestness succumbed to an allegorical fervor that today we might soberly assess as berserk.

Influenced by the overripe classicism of Paris’ Ecole des Beaux-Arts, where many of them were trained, American sculptors busily went about fashioning figures that represented gods and heroes and the fates of nations. The male figures were graced with impeccable musculature; the women were typically winged, with flowing robes and long, sad faces, holding aloft torches that represented some unquenchable truth.

It was a style that suited exactly the fervid emotional makeup of Pompeo Coppini. Many years later, for example, he could sit down and write with poker-faced conviction this description of a tablet he had made for New York’s Consolidated Gas Company: “At the right is the figure of Womanhood, emancipated by gas and electricity from age-long drudgery. At her left is the sturdy figure of Labor, releasing the forces which bring to the metropolis the immeasurable blessings of gas, electricity and steam. The torch symbolizes enlightened human progress. The palms pay homage to those achievements of the Consolidated Gas Company of New York and its affiliated companies.”

But for all his natural empathy with the fashionable aesthetic, Coppini did not meet with great success in New York. He found that the commissions always went to the same Anglo-Saxon clique and that the system gave “undue power to a very few unscrupulous art racketeers.”

If Coppini’s genius was not immediately recognized, he was at least able to find employment, sculpting figures in a wax museum and assisting the established Anglo-Saxons who had robbed him of his commissions. And with his unerring instinct for patronage and political advantage he managed to situate himself in the right salons.

Still, he notes cryptically in his autobiography, he was “living a rather dissipated life, in which I became so disgusted as to have my faith in . . . the glorification of womanhood badly shaken.” That glorification was redeemed just in time when he met Miss Elizabeth Di Barbieri, who came to model, properly chaperoned, for a figure of Columbia that Coppini had been hired to create for a memorial to Francis Scott Key. Coppini fell in love with his model’s “beautiful, queenly” countenance, and not long after, they were married.

Work continued to come Coppini’s way. In one instance he was engaged to execute a sixteen-foot-high group featuring an eagle with an eight-foot wingspan and two “allegorical” babies, a massive assignment that took him all of two days. But he was still impatient, and still convinced—as he would remain all his life—that the envy and treachery of less talented sculptors was holding him back. He was on the verge of returning to Europe when he heard about a job in Texas. The call had gone out for a sculptor who would be willing to create a nine-foot statue of Jefferson Davis—part of a Confederate memorial to be placed on the state capitol grounds—for 75 cents an hour. Coppini look a hard look at his career. By his ambitious standards it was stalled, and in New York the steep heights to glory were crowded with climbers. He had little to lose by taking a flier in Texas. So he bought a train ticket for San Antonio and headed south toward the city where he trusted he would finally make his name.

“I WAS REBORN A TEXAN,” he tells us. San Antonio, with its sharp sunlight, its village atmosphere and sleepy cosmopolitan mores, reminded him of his native Italy, and he suffered no hesitation in adopting it as his home, especially when he noticed that for a sculptor it was almost virgin territory. His first order of business was the Jefferson Davis statue, which he quickly tossed off. In nine days it was ready to be cast in plaster, a point that would have taken another sculptor half a year to reach. Coppini assembled the dumbfounded committee to approve his work, and they were so pleased that they rejected four statues that had already been completed for the memorial by other sculptors and reassigned them to Coppini.

In San Antonio he saw the opportunity not only to be a working artist but to be a celebrity as well. A flamboyant smock-clad Italian sculptor was just what this somnolent town seemed to need, and before long Coppini and Lizzie (as he called his wife) found themselves cozily established among the people who were most able to advance his interests.

“I became more and more popular every day,” he does not shrink from reporting. He was staple copy in the newspapers, which dutifully reported on the progress of his works and kept San Antonians abreast of his municipal activities, which were legion. Coppini, almost from the moment he stepped off the train, was a full-bore civic dynamo, throwing his formidable energy behind a host of causes: the building of an outdoor amphitheater, the creation of a civic art league, the fight to save the ruins of the Alamo. He opened a short-lived art school, chided Texans for ignoring “their magnificent, romantic, and tragic history,” and continued to secure commissions, making bronze portrait statues of late lamented businessmen that caused widows and grandchildren to weep with the shock of recognition.

In 1905 he won a state competition to create an equestrian statue in honor of Terry’s Texas Rangers that would be placed on the Capitol grounds along with his memorial to the Confederacy. Seventeen people had formally entered the competition, not including Elisabet Ney, the famous Bavarian-born sculptor who at that time held the field in Texas. She had remained above the fray on this commission, expecting it to come to her by virtue of her reputation, as a matter of simple artistic justice. When the equestrian statue was awarded to Coppini, she was not amused.

“Alas!” she wrote to the editor of the Austin Statesman, “It seems the mere word Italian stands by most people here in Texas for greatness in art. It is a great pity that Texas can again be duped.”

Coppini took that slap with rare poise: “I paid not much attention to her ‘meow,’ for after all I realized that it must have worried her to get someone else in her field, especially an aggressive, ambitious young man, who had given proof of real ability.”

Ney was not the only one who felt threatened by the Coppini juggernaut. Stonecutters and monument dealers, to whom public artworks had routinely been assigned, were hostile to the idea of a sculptor who worked in bronze. Characteristically, Coppini cultivated their attacks, preferring to view them as assaults by philistines upon the temple of art rather than as the logical outcome of a turf battle in which all the participants were equipped with titanic egos. Everywhere he turned he saw “human termites,” “cold-blooded betrayal,” “dirty, unethical and calumnious stories.” His enemies were numberless. Sometimes, when it was no longer enough to rant about the forces of unenlightenment, he would grab a bullwhip, rush out the back door, and begin picking off innocent chickens.

But for all his complaints, Coppini had eclipsed Ney as the most prominent sculptor in Texas. He was a fixture in San Antonio society, the intimate of mayors, governors, land barons like the Klebergs. He belonged to the Ben Hur Shriner’s Patrol and the Friends of the Circus and was a founder of the Chili Thirteen, the group that initiated San Antonio’s Fiesta week.

In 1909, after securing commissions for the Sam Houston Memorial in Huntsville and the Texas Pioneer Monument in Gonzales, Coppini began to build his great home on Madeline Terrace. It included a studio with a 35-foot-high ceiling, which was outfitted with traveling cranes that rolled on steel beams and could lift a ton apiece. There was also a special concrete vault whose cool interior could hold two tons of clay. Nearby, Coppini built an art gallery where he displayed models and plaster casts of his works.

The Madeline Terrace house was the showcase residence of a celebrity sculptor at the zenith of his reputation. He was famous in San Antonio and in every little town in Texas, at least among the ladies in those communities who met regularly to discuss the finer things. The Tuesday Club, in the West Texas town of Brady, was one such group. In 1910 its members wrote to Coppini to alert him to the presence in their midst of a gifted young sculptor, and to ask if he would consider taking her on as a student.

WALDINE TAUCH AT THAT TIME was eighteen years old, beautiful and ambitious, devoted to her loving but difficult family. She had been a cause of the women at the Tuesday Club for several years, ever since they had first seen the animals and angels she had carved out of soap and chalk with her father’s pocketknife or modeled in the moist clay she had dug from the garden.

Her father, like Pompeo Coppini’s, was a failed artist, whose dreams of supporting his family as a photographer were consistently at odds with the hard realities of rural Texas. Her mother suffered as Coppini’s mother had, from a jealous distrust of her husband and from dangerous morbid spells that culminated in a suicide attempt one gruesome night when Waldine was seventeen. Mrs. Tauch had been in the middle of preparing dinner when she suddenly stopped and asked Waldine to accompany her outside. In the backyard, while the girl watched helplessly, her mother pulled a butcher knife from under her apron and cut her own throat.

The knife missed the jugular, and Waldine’s mother survived. Later the shaken family moved from their ranch into Brady, where the ladies of the Tuesday Club held dinners and bake sales to pay for Waldine’s education, which they were determined would take place under the great Coppini.

But Coppini balked when he received their letter. Sculpture was a man’s art. It required ruthless dedication and abundant physical strength. It was not a pastime but a calling, and Coppini had little faith that a young woman could overcome the distractions of marriage and family to rivet her full attention upon Fine Art.

Certainly the construction of a full-scale statue was a project that demanded an almost religious commitment. More than art was involved. Engineering skill was required, along with endurance and extraordinary concentration. The process began with a small “sketch” made in clay, itself the result of prodigious research into the subject’s appearance and dress. The sketch served as a reference in constructing the actual work, which was often a project of daunting size and mass. Coppini would begin by building an armature in his studio, screwing pieces of pipe together to make a crude skeleton whose form he embellished with scraps of wood until it bore a ghostly resemblance to a human shape. The armature was critical; it was where the soul of the sculpture secretly resided, and so the pipe fitting and carpentry not only had to be solid enough to support tons of clay, it had to be artful as well. Once the armature was finished, Coppini began the arduous task of fleshing it out with clay or—in prosperous times—plastilina, an expensive oil-based modeling material that had the advantage of never drying out. Bucketloads of clay had to be hauled up ladders and scaffolds by hand.

The actual sculpting was less grueling, at least in terms of physical effort. When Coppini was finished modeling, he made a plaster cast, a complicated task in which the original clay figure was destroyed and reincarnated as several dozen bits and pieces of hollow plaster that fit together like a puzzle. This puzzle was then shipped to a foundry, where, if it arrived without damage, it was cast in bronze.

Coppini was doubtful that a mere girl would have the devotion to endure such labor-intensive procedures, no matter what the Brady Tuesday Club thought of her. But the ladies persisted, and when Coppini finally agreed to see her sculpture for himself he was impressed enough to accept her as a student.

Ignoring her last few weeks of high school and a proposal of marriage, Waldine went to San Antonio to live with the childless Coppinis in their ornate mansion. With “Mother Coppini” she developed a deep and immediate rapport. The great sculptor himself took some getting used to. That first night in his house he lectured the awestruck girl on the sacrifices an artist must make for his art and left her with the clear impression that he expected her never to marry.

She found him to be an overbearing teacher, a temperamental perfectionist who would tear up a bust she was working on if he found even one detail that did not please him. She was his assistant as well as his student, expected to lug heavy buckets of clay up to him on the scaffold. She went to bed each night aching with muscle fatigue and stung by his verbal abuse. But Waldine was confident and ambitious, and her skills grew under Coppini’s harsh direction. His assertions that she was too small and weak ever to create monumental works only spurred her desire to succeed.

Gradually the master-slave relationship softened, until Waldine began to see Coppini as a mentor and, in the fullness of time, as a colleague. She became as well a surrogate daughter to the Coppinis, so much a part of their household that several years after she came to live with them Coppini wrote a letter to Waldine’s parents, without her knowledge, proposing to adopt her and give her the benefit of his name. Waldine’s parents, alarmed by the sculptor’s presumption, moved to San Antonio to regain control of their daughter. The tug-of-war ended in a more or less amicable draw, but Waldine’s intense, complex fealty to the Coppinis never slackened.

Coppini had lived in the Madeline Terrace house for only five years when his fortunes began to turn. “I was running in a vein of deep, bad luck,” he writes of this time at the eve of World War I, when the funding of public art was suddenly one of the last priorities of an apprehensive nation. One by one, the commissions he expected fell through, and Coppini could no longer afford the lavish entertainments that had made him one of the most visible fixtures in San Antonio society. Soon he could not even afford the maintenance of his house and servants. Feeling betrayed by the seeming indifference of his rich acquaintances, he sold the home to a Corsicana oilman and set out in 1916 for Chicago. Before he left, one of his many clubs threw a banquet, where another of his versifying friends expressed hope that he would find “sufficient lucre” in the Windy City and promised that

Our bosoms will be thrilled

With the thought that once Coppini

Dwelt among us; and his spell

O’er us, with its inspiration,

Like a benediction fell.

WE MUST NOT THINK of Coppini at this point in his life as a starving artist. He had enough cash on hand when he arrived in Chicago to buy a three-story stone house on Grand Boulevard and rent a studio. But his pile of lucre was dwindling, and commissions were no easier to come by in Chicago than they had been in Texas.

But it was a Texas commission, ironically, that proved to be his salvation. Less than a year after Coppini had left the state in defeat he was summoned back, by a Menard County rancher named Gus Noyes. Noyes was a wealthy, plainliving, heartbroken man whose twenty-year-old son had recently died in a fall from his favorite horse. The old man wanted Coppini to make a bronze statue of the boy and the horse and erect it at the spot where he had died.

In his autobiography, which otherwise is filled with pompous self-regard and windy paranoia, Coppini writes with surprising pathos of his first meeting with the shattered rancher.

I was met at the train by Mr. Noyes and his little daughter, Aileen, in a Dodge car, and taken to the ranch home. As I looked at the simple way those people were living, the poor clothes they were all wearing, the scanty furnishings of a very poor people’s home, and the unshaved, sad-looking face of Mr. Noyes, I became almost frightened that I might have been misled in an impossible prospect of a dream of an unusual work, and a luxury trip for me at the time when I surely could not have afforded so much gambling. I was scared to talk, as I hated to show what was passing in my mind, and the . . . old man sat by the fireplace, with no fire in it, gazing as if there was a flame, and saying nothing and asking me no questions.

With three faded Kodak photographs of Noyes’ son, Coppini went back to his Chicago studio and set to work. By the time the statue was ready to be erected Noyes himself had moved to Florida, wanting away from the country that was a constant reminder to him of his lost son. The memorial was ultimately situated in the townsquare of Ballinger and not, as originally planned, on the site where the boy had died. Noyes did not attend the unveiling, but Coppini was there at the rancher’s request and was incensed at the seeming indifference of the town to a work he considered one of his best.

While he was working on the Noyes sculpture, Coppini landed another important Texas commission, although it was a project whose problems would dog the sculptor for the next fourteen years and whose outcome would always be a bitter reminder to Coppini of the ceaseless battle between Greed and Art.

The Littlefield Fountain, as the work would ultimately be known, began in the mind of Major George W. Littlefield, the Civil War veteran and former chairman of the University of Texas Board of Regents. Coppini had become friendly with him while modeling his portrait bust. It was Littlefield’s idea to erect a commemorative arch at the university honoring the old major’s favorite heroes, an eclectic panoply that included Woodrow Wilson, Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and former Texas governor James C. Hogg, who had weighed 350 pounds in life and would weigh many times that in bronze. Coppini suggested a fountain instead of an arch and proposed that the whole structure be a memorial to those university students who had lost their lives in World War I.

Littlefield agreed with Coppini’s conception and earmarked $250,000 of his own fortune for the project, $50,000 short of Coppini’s estimated cost. Littlefield, who was in poor health and did not expect to live to see the fountain completed, promised the sculptor that his heirs would make up the difference.

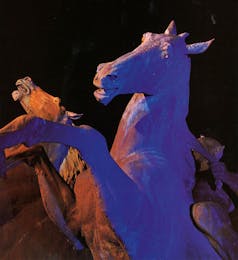

The Littlefield Fountain was an immense undertaking, a sculptural group that called for eight larger-than-life portrait statues to flank a centerpiece that featured three gigantic “sea horses” and the prow of the Ship of State, complete with the requisite female entity sprouting wings and bearing torches. In order to accommodate such a mammoth project, Coppini moved to New York, closer to the best foundries, and bought a five-story building on West Fourteenth Street, where he built a studio and threw elaborate parties that featured the talents of, among others, Tex Ritter.

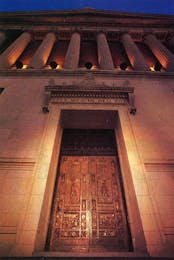

Waldine Tauch moved to New York to help the sculptor assemble the armature for the three rearing horses that were to be the focal point of the fountain. During this time Coppini took on other assignments, notably the bronze allegorical doors to the new Scottish Rite Cathedral in San Antonio (Coppini was a devout Mason) and a statue of George Washington for Portland, Oregon. He also traveled to Texas often, addressing Lions Clubs and Rotary conventions and generally making sure that the citizens of his adopted state remembered that he had once dwelt among them.

The Littlefield Fountain was by far his largest project and one that by all rights should have remained close to his heart. But by the time it was perfunctorily dedicated in 1933 he had all but disowned it. The Littlefield heirs, as it turned out, did not have the sentimental attachment to the project that Major Littlefield had, and once they discovered the true cost of the monument they managed to transfer their responsibility in the affair to the University of Texas. The university erected the fountain in a cost-cutting, businesslike way that left Coppini livid, since it did away with the granite pylons and terrazzo walkways he had envisioned and scattered the statues of Littlefield’s heroes all along the south mall, instead of grouping them in a Court of Honor near the fountain.

The Littlefield Fountain remains, along with the Alamo Cenotaph, Coppini’s most visible work. But it did not please the artist himself, and its appearance on the campus uncaged J. Frank Dobie, who would from that moment forth remain Coppini’s nemesis. “It is a conglomeration,” Dobie wrote, “of a woman standing up with arms and hands that look like stalks of Spanish daggers, horses with wings on their feet aimlessly ridden by some sad figure of the male sex and of various other paraphernalia.” Dobie twisted the knife by suggesting, during World War II, that it be sold as scrap metal to aid the war effort.

But the Littlefield Fountain was allowed to stand, and it has been a fixture of campus life for generations of UT students who have routinely dumped detergent or bubble bath into its pool, along with an occasional live alligator, but who have remained blithely indifferent to its meaning as art. It is unlikely that those few students who may have paused at the fountain to scratch their heads over its significance would have guessed that the horse—equipped with stubby wings on their flanks and, in place of hooves, fan-shaped fins that look like mud flaps—represent the forces of Mob Hysteria. Two of the horses are under control, ridden by mermen with pompadour-shaped fins on their heads, who are busy reining in the riderless horse. Such is the manner in which Pompeo Coppini depicted the Value of Manpower.

IN HIS SIXTH DECADE Coppini was more mindful than ever of the judgments of posterity. Searching for inspiration, for the great work that would be the capstone to his career, his thoughts returned once again to Texas. “I want to build a monument to the Alamo Heroes now,” he wrote in a letter to Clara Driscoll. “I want to put in it all my love, all my devotion, all my art. I feel that no other living artist can fill my place.”

Ever since Coppini had first been reborn a Texan, he had embraced the story of the Alamo with the zeal of a convert. Men nobly choosing not to surrender, creating in the crucible of their deaths an ideal of freedom; where was there a better example in history of Moral Earnestness?

It was an uphill fight for Coppini to land such a commission. As the year of the Texas centennial approached, there was no agreement that there even should be such a memorial. (“The very idea,” said the San Antonio Light, “of a monument to the Alamo, right beside the Alamo, bordered on the act of lighting a candle in order to illuminate the sun.”) Once the idea had taken hold, however, there were a great many sculptors who wanted the job, and Coppini was not always at the top of the list. By now he had some powerful enemies, not the least of whom was the archfiend J. Frank Dobie, who was running amok, telling interested parties that Coppini had “littered up Texas with his monstrosities in the name of sculpture.”

Coppini’s friends urged him to sue, but he brushed off Dobie’s “drunken venom” and applied himself to the greater goal of winning the commission. He succeeded, but it took every bit of the political and social clout that he had so assiduously developed since he had first set foot in Texas 35 years earlier.

With the commission in his pocket, Coppini finally came home, returning to San Antonio and building a house and studio on Melrose Street. The Coppinis shared their new residence with Waldine Tauch, who was now an established sculptor in her own right, having completed, among other works, a fifteen-foot-high statue of Moses Austin for San Antonio’s city hall.

The monument to the Alamo defenders was conceived as a cenotaph, an empty tomb, with an imposing angelic figure—the Spirit of Sacrifice—soaring upward on one face of the high monument, rising from the funeral pyre that had consumed the heroes’ bodies. On the opposite face, wearing a laurel crown and gazing serenely outward, stood the Spirit of Texas. The flanks of the monument were devoted to the defenders themselves, with Bowie, Travis, Crockett, and Bonham standing out in three dimensions while their comrades faded into relief behind them.

“The humming of building the many large armatures for the various statues was music to my ears that made me happy,” Coppini recalled. “I never felt tired and always hated for darkness to come.”

But there were still obstacles and disappointments. The final design of the cenotaph structure itself was in the hands of a group of architects, and so above the statues and reliefs that Coppini had created rose something that looked very much as if it had been designed by a committee, a truncated vertical vault that had all the appeal of, as J. Frank Dobie could not resist suggesting, a grain elevator.

Coppini had originally envisioned the cenotaph with a base of granite, upon which the various heroes and spirits would be set in bronze. But the decision was made to make the whole thing out of marble, a medium the sculptor feared would not hold up as well in the Texas climate. Resignedly, Coppini shipped the plaster casts of his figures to a Georgia marble quarry where, instead of being cast in bronze, they were reproduced in stone by duplicating machines.

If the final form of the cenotaph was not everything Coppini had dreamed it would be, at least he had done it; he had proved his devotion to the state of Texas and made a monument that put his work—quite literally—on the map. Dobie, typically, hated it. He objected to, among other things, the picturesque poses of Crockett et al., asserting that they “looked as though they came to the Alamo to have their pictures taken.”

“Such sissies he would make you believe they look to be,” Coppini fumed. “But I am happy not to have sent to posterity our Alamo heroes like horrible, disgusting, low types of manhood, shabbily clothed and wild in appearance.”

Coppini did not respond to such attacks with the vehemence he once might have. “After the Cenotaph,” he writes, “I fell in a complete state of lethargy.” He was older, his sculptor’s constitution was fading, and no doubt he sensed that the great commissions were behind him.

In 1943 he was offered the chairmanship of the fine arts department at Trinity University, a position he accepted on two conditions: that the university “accept the challenge I would provoke to the modern primitive schools” and that Waldine Tauch be hired as his assistant. He taught at Trinity for two years and then went back to his sculpture, seeking inspiration but finding only disillusionment. In some complicated way he seemed to believe that World War II was a symptom of modern art, a triumph of the inchoate over the pure and refined, a refusal of mankind to listen to the “inner divine counsel” that was the voice of the true artist.

“I will use my art as a warning,” he thought, “against the criminal spreading of atomic power and energy.” With renewed inspiration, he created a small statue of “a new pagan god” named Atom, half demon and half angel, holding a bomb in his right hand but with “his head turned toward the left, which is troubled by his heart. . . . From the back he appears as a messenger of great Evil. . . . But he is about to take another step. . . . Will it be backward or forward, toward his redemption? It will be up to us mortals to help him to decide his forward step.”

Coppini believed that perhaps, if a full-scale version of the statue could be made, it could help avert the global annihilation that he feared. But he could find no one to put up the money for him to sculpt it and cast it in bronze.

He died in 1957, at the age of 87. On his deathbed he told Waldine Tauch that he had been so harsh with her in the early days only to test her, to see if she had what it took to be a sculptor. She did. “You’ve been a wonderful daughter,” he told her.

COPPINI’S GREAT HOUSE on Madeline Terrace has long been demolished, but the house on Melrose, in whose studio he created the Alamo Cenotaph, is still there. It is now the home of the Coppini Academy of Fine Arts, a nonprofit organization chartered “to encourage worthy accomplishment in the field of art.”

Waldine Tauch is president emeritus of the academy. She is 92, still lucid and forthright. “Let me see what you look like,” she says, flipping up her outfielder’s sunglasses and standing on her toes so that she can peer directly into her visitor’s face. It would have pleased Coppini to know that she never married, that she led her artist’s life with a rigorous focus. Since his death she has made many statues, most notably an eight-foot-high portrait of General MacArthur for the Douglas MacArthur Academy of Freedom in Brownwood, which she completed when she was 78.

Dr. Tauch—she has an honorary degree from Howard Payne University—is retired now, and the studio where she and Coppini worked, its floor and shelf space cluttered with models and plaster casts, has a hallowed air about it. She speaks of Coppini only in the most solemn tones, as befits a foster daughter. “He was a wonderful, outgoing man,” she says. “He really loved people, to talk to them, to get information. He loved San Antonio. He was into everything here. And he loved America. I don’t think anyone loved America more than he did.

“Sculpture,” she says, “was something inside of him. He loved it with all his heart and soul.” She doesn’t care for modern art, the “primitivism” against which Coppini had waged his holy war, but she seems sadly reconciled to its presence. “The only thing I can say is let them do it if that’s what they want to do,” she says, “but it doesn’t mean much to me.”

What about the kind of work she and Coppini had done, the heroic monuments untainted by irony and consecrated to some ethereal cause? Why is no one doing that kind of sculpture anymore? Because it’s too expensive? Because it’s simply out of fashion?

“No,” she says, with a challenging edge to her voice. “Because it’s too hard.”

Whatever one ultimately thinks of Pompeo Coppini’s sculpture, it is hard to work up much sympathy for J. Frank Dobie’s assertion that Coppini “littered the landscape” with his work. Endurance has a way of blunting criticism, and by now Coppini’s sculptures are a part of the landscape itself and seem to exist by some sort of natural right. Besides, the best of them are very good: the Terry’s Texas Rangers equestrian monument displays great verve and kinetic understanding; the James C. Hogg statue at the University of Texas, part of the misplaced Court of Honor to the Littlefield Fountain, is remarkable for the tact with which it makes the governor’s obesity a compelling focal point; and finally, there is the Noyes memorial in Ballinger, which has no credo to express other than the simple fact of loss.

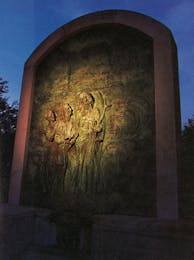

There is another monument, slightly more removed from public view than the rest. It sits, or rather looms, in San Antonio’s Sunset Cemetery, a twenty-foot-high structure of marble and bronze, placed so that shadows will never fall completely across its face. This is the tombstone that Coppini designed for himself.

It’s a strange work, featuring a full-sized bas-relief of Coppini himself, with an entreating look on his face, gazing up into the eyes of a winged patriarchal figure. Behind Coppini is his wife, her hand gripping his shoulder in unquestioning loyalty. The bronze is streaked and green, in need of cleaning, and seems to be hiding some ancient secret. Behind Coppini and the rest of the group are swirling clouds, a disembodied eye, and two mythical figures hovering in a corner. Highly symbolic, charged with mystery and stalwart sentiments, this sculpture could well be the last gasp of Moral Earnestness. It is Coppini’s answer, from beyond the grave, to the frivolous scrapheap forms that have superseded his passionate ideal of public sculpture.

But in its way this tomb is as inexplicable as those abstract forms. One could stand in front of it for a long time before understanding it, before realizing that the winged figure is Father Time, and that Pompeo Coppini, Sculptor, is asking him for one more chance.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Art

- Sculpture

- Longreads

- San Antonio