This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

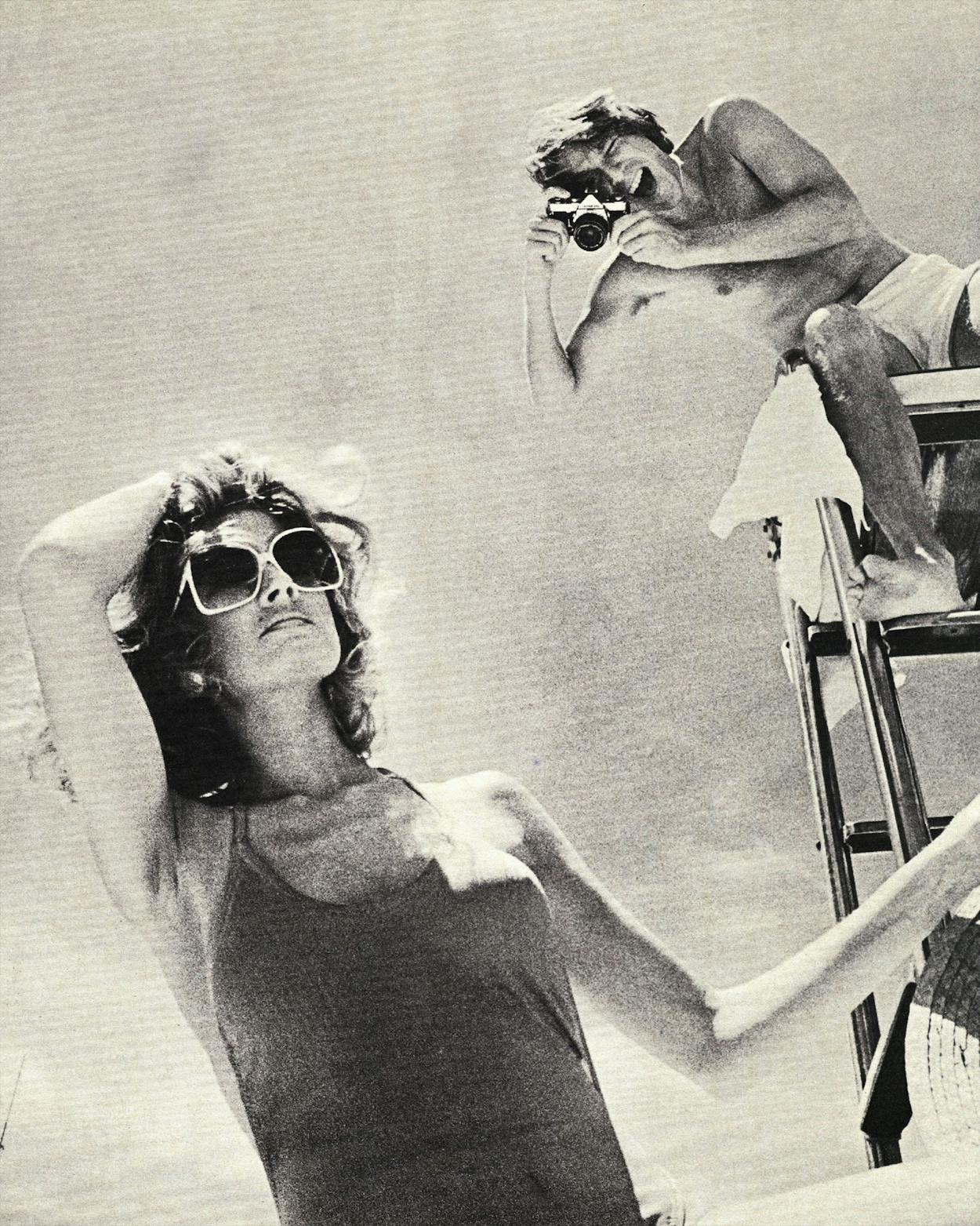

I was watching a late-night television show when I got the message. It came—as much cultural insight does these days—via a commercial. Suddenly, there was John “Newk ” Newcombe, Wimbledon tennis ace and naturalized Texan, putting down his tennis racket and picking up a smallish 35mm camera. Holding it as if it were a tire tool, Newk fired off a few snaps. Then his handiwork appeared on the screen. The photos were rather nice action shots of a female tennis player. There was nothing spectacular about them and yet they had a certain appeal. They were well composed, in focus, properly exposed. And Newk, mind you, though he may be a pro with a racket, is not one with a camera. The message was clear: anybody can do it

And everybody seems to be. Polaroid is working double shifts. Eastman Kodak can’t keep film on the shelves. Rolling Stone, the magazine of the rock music culture, devoted an entire issue to the work of portrait artist Richard Avedon, while at Avedon’s old haunt, Vogue, new gun Deborah Turbeville is waking up that magazine’s readership with a series of breakthrough fashion photographs that look like they were taken while the photographer was at a seance. Books of photographs are selling off the shelves, and old prints are bringing five and ten times what they sold for five years ago.

Good photography is everywhere. On album covers. In the subways. Hiding in those weird little magazines that airlines put out for their passengers. Lavishly displayed across manicured corporate annual reports (“Who shot your brochure this year, J. P.?”). Why is photography so hot? Because photographs “read”—convey information—quicker and with more immediacy than print. In today’s world, reading lots of words is something many people don’t have the time or inclination to do. Reading photographs and small clusters of words, such as you find in Architectural Digest, or People, or Vogue is more suited to some folks’ lifestyle. Others even buy foreign magazines and “read” them by just looking at the photographs. The key factor behind the growth of photography has always been awareness —a keenness of vision and ability to turn the ordinary into the special. Gifted photographer Diane Arbus, who recorded a strange side of life inhabited by giants, dwarfs, and other misfits, summed it up when she said, “If I hadn’t taken the photo, no one would have noticed.”

Photography—always a folk art—is gaining public acclaim as a fine art. The number of photographic galleries in New York has leaped from six to thirty in just five years; three are now operating in Texas. Photography is accepted at fine museums and galleries. Ansel Adams hangs nearby Morris Louis. An original Steichen is in the same exhibit with an original Seurat. The benediction of the art establishment has created an atmosphere in which photography can be taken seriously.

None of those things, however, is what photography is ultimately about, just as art criticism is not what painting is ultimately about. Photography is a street art, an art made for participation. Taking it too seriously sometimes clouds the most important issue: that photography is our most accessible art form.

Unlike painting, music, and sculpture, photography holds the possibility of success on the very first try. Let’s face it; it is not that big a deal to take a picture. You see something interesting, you shoot it. The lack of style is a style. Basic photographic principles—exposure, depth of field, shutter speed—can be picked up in an afternoon. Now the fine points, the techniques, those don’t come in an afternoon, or a year of afternoons. Those are developed through trial and error, repetition, boundary-breaking, inspiration, and—most important—a singular kind of vision, the ability to snap the shutter at what world-famous photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson calls “the decisive moment.” That is the art of photography.

But, as you are aware by now, photography is getting a big push as a folk art. The time is right, the culture is visually attuned, the people are ready. Photography is moving out of the commercial studios and off the pages of the best books and magazines into the uncharted cultural territory we call lifestyle. A Kodak in every kitchen? A Hasselblad in every home? Can this be?

You bet. And so do the camera companies. That’s why they are busily removing the last hurdle to high quality photography for the masses: the camera. The camera slowed a lot of us up—all those dials and buttons, the color-coded depth-of-field scales, the shutter speeds, the f-stops, the ASA settings, all that. Photography should be simple, because far more people are interested in photography than are interested in cameras. That’s sound logic, but for awhile it escaped the people who make the best and most flexible camera: the 35mm SLR (single lens reflex). There’s a lot to be said for the point-and-shoot Instamatics and Polaroids, but you can get far better quality with a 35mm SLR.

The most popular modern camera, the SLR, uses a single lens for both viewing and exposure; the image is reflected to your eye by a mirror that swings aside when the shutter is snapped to let the light strike the film. Because of its design, a 35mm SLR does more things more successfully than any other camera. It’s versatile, accurate, fast, light, and relatively inexpensive for the quality you get. But where 35mm SLRs really outstrip the quickies is in the fine points, like the viewing system. With the 35mm SLR’s accurate viewfinder system, you can see more than 90 per cent of the film frame—what you see is what you get—so you can make the right decisions about composition.

If viewing precision is the most important feature of the modern 35mm, flexibility runs a close second. Today’s 35mm SLRs are “systems” cameras, which means that you can get close-up accessories, motor drives for sports or fast-action scenes, remote control to let you photograph charging rhinos, scientific gear for time-lapse photography, underwater accessories, you name it.

Another important aspect of 35mm SLR design—and another area where it differs from the Instamatics, Prontos, and other such hardware—is lens interchangeability. You can mount a wide variety of lenses on a 35mm SLR in order to meet a wide variety of photographic needs. You can use telephoto lenses to bring things up close when you’re not, macro lenses to photograph flowers a few inches from your nose.

In short, the modern 35mm SLR is a remarkable invention, capable of heroic performance in the hands of a good photographer. It is in almost every pro’s outfit because it’s the most basic piece of equipment he could own. And now in its newly automated incarnation, it’s becoming accessible to every weekend photographer.

Fear not the f-stop. Do not shudder at shutter speeds. With the new SLRs, technology does the numbers. You just keep your eye to the viewfinder and press the shutter at the decisive moment.

The new generation of 35mm SLRs (around since 1975) are extremely automatic—they do the exposure and other technical settings with minimal manual input—leaving you to focus on what’s important: the photograph. The new cameras are in general as easy to use as a Polaroid or an Instamatic. They are smaller than the traditional 35mm SLRs, for increased ease of handling and portability. And, as stated, they rely on electronics to do the hard work for you (the old-style 35mm SLRs were operated mechanically, instead).

So what does it all mean? Simply this: photography is the medium of our times. The tools of awareness have become easy to use, and in the process photography is expanding its base as a folk art. Seeing is believing, friends.

Hot Shots

Canon AE-1

Canon is the company that revolutionized the automatic 35mm market, and the AE-1 is the product they did it with. The AE-1 was the first camera to use computer technology. The AE-l’s brain-on-a-chip circuitry not only monitors the camera’s light-metering functions but also allows the replacement of many mechanical parts with electronic circuits, a swap that results in better accuracy and reliability.

Going against industry trend, Canon designed the AE-1 ($320 with 50mm fl.8 lens) as a shutter-preferred automatic (you select the shutter speed, the camera selects the correct f-stop); but the AE-1 can also be operated manually. One interesting feature of the AE-1 is the fact that the camera can be operated automatically even if you attach a strobe light (the Canon Speedlite 155a at $50–$60). Or if you wish, the Speedlite will set both aperture and shutter speed.

The AE-1 will accept all of the Canon FD lenses, but it does not have exceptional versatility. If you want systems performance with Canon equipment, you’ll have to move up to the top-of-the-line F-l model. However, the AE-1 will accept Canon’s Power Winder a ($100). The AE-1 has been such a resounding success that it has already been copied by a large number of manufacturers.

Nikon FM

You wouldn’t expect a prestigious company like Nikon—numero uno in status and reputation in the 35mm camera business—to get left behind in the race to develop the new generation of 35mm SLRs, but that’s exactly what happened. Nikon failed, at first, to realize the significance of the automatic, despite the enormous popularity of its own 35mm automatic, the Nikkormat EL. Nikon also misread the move toward compacts. Left at the starting gate by a host of aggressive competitors, Nikon is having to play catch-up.

Nikon is a tough customer in the camera business, and it wasted no time in revamping its product line. For openers it raised the well-received Nikkormat EL (last produced as the Nikkormat ELW) to Nikon status by simply changing the label. The Nikkormat ELW is now the Nikon EL2 ($500 with 50mm f2 lens), and the significance of the Nikon name on an automatic camera should not be missed. Previously “Nikon” had been reserved for the company’s top-of-the-line semi-automatic model. With the change, Nikon has indicated that it has every intention of becoming number one in automatics. In addition, the EL2 also has the new Nikon automatic indexing lens system for full-aperture metering. This mouthful simply means that it’s faster and easier to change lenses than it was with the old Nikon system of external indexing. This is a change that was long overdue and is now standard on all Nikon models except the Nikonos III.

The big news at Nikon centers on the introduction of Nikon’s first compact 35mm SLR: the Nikon FM ($380 with 50mm f2 lens). The Nikon FM is not an automatic SLR but it’s almost as simple to operate because of the manner in which the built-in light meter functions.

The light meter displays the correct exposure setting or reading via a light-emitting diode (LED) readout, rather like a small computer display screen that you see when you look through the viewfinder. Adjust the camera until the correct combination of lights comes on, and you’ve got the proper exposure. The simplicity of LED operation gives the Nikon FM the convenience of virtually automatic operation with the ultimate user control of a manual.

The new FM uses the recently introduced line of AI-Nikkor (auto indexing) lenses, so lens changing is fast. The FM is designed to accept a wide variety of Nikon system accessories, but the most popular option is probably going to be the MD-11 motor drive ($200). The compact MD-11 will provide continuous operation at 3.5 frames per second; photojournalists and sports photographers are going to love it. Even fitted out with a motor drive, the FM is not much heavier than a conventional 35mm SLR.

Olympus OM-2

Olympus pioneered compact 35mm SLRs with its trend-setting OM-1 model (still available and still desirable), but now the company has readied another trend setter for market: the automatic OM-2. The OM-2 is a true compact automatic, and it’s going to be every bit as influential in the camera marketplace as the OM-1 was when it was introduced four years ago.

The OM-2 ($400 plus lens) is the same size as the OM-1—the two cameras are look-alikes—but it scores impressive points with its unique silicon blue automatic exposure system (about which more later). The OM-2 will give you a choice of automatic or manual operation, of course, but you’ll probably find that most of your shots are taken on automatic because the exposure system is so accurate. The control used on the OM-2 is of the aperture-preferred variety. An extremely fast and sensitive silicon blue cell measures the light reflected off the film curtain during the instant before the film is exposed and sets the shutter accordingly. It’s a fancy bit of engineering, and it’s especially helpful when you’re shooting with a motor drive under varying light conditions because it assures correct frame-by-frame exposure.

The size and ease of handling of the Olympus OM-1 were always that camera’s drawing cards, and the OM-2 retains those characteristics. Like the OM-1, the OM-2 is extremely quiet due to its air-damped mirror-return system. The viewfinder is large and bright, and the camera has a crisp feel to it. The OM-2 is a systems camera, so you can count on an array of specialized accessories to handle any situation from shooting sports with a motor drive to shooting butterflies with a macro lens.

With the OM-2, Olympus has pushed state-of-the-art technology to a new level. I admire the company’s foresight and its pluck for moving to smaller, less obtrusive camera designs. Olympus might make a small camera, but it is a large force in the current marketplace, and its compacts are quickly gaining good reputations, especially among younger 35mm users. Equipped with the Winder 1 ($150), and the Zuiko 75mm–150mm zoom ($300), the OM-2 is a very handy piece of equipment.

Pentax ME

Pentax has always been something of an enigma in the U.S. because its fine cameras have never had the mass recognition and support they deserve. Pentax is the largest camera company of the big five (the others are Nikon, Minolta, Canon, and Olympus) with five factories—four in Japan and one in Hong Kong—cranking out cameras night and day. Pentax marketed the first 35mm SLR in Japan, gave the world the first instant-return mirror (an essential component of modern SLR design), and the first behind-the-lens light meter (a design advance made back in 1960).

Now Pentax has decided to make its move in the 35mm field by introducing two new compacts, one automatic (the Pentax ME), one manual (the Pentax MX). The ME ($340 with 50mm fl.7 lens) is the smallest 35mm SLR currently on the market. It is extremely light (a mere 16.2 ounces) and completely automatic, using the aperture-preferred exposure system. There are no cryptic needles in the viewfinder; all exposure information is communicated with a simple light-emitting diode (LED) readout in the viewfinder. The ME’s metering system is built around a gallium arsenic phosphorus photo diode (GPD) circuit that is claimed to give greater accuracy under a wide variety of lighting conditions than conventional cadmium sulfide cells. The camera’s electronic circuitry saves current (and hence batteries).

Pentax is planning a large system of photographic accessories to go with the new ME and MX. They have also produced a new line of compact bayonet-mount lenses that make lens changing much quicker than it was with the old screw mounts. The ME will also accept an autowinder, the Winder ME ($130), to advance film at the rate of almost two frames per second. The advertising and promotional support that Pentax is putting behind its new ME and MX models show the company is serious about becoming number one in the United States.

Polaroid SX-70 Alpha 1

Surprised to find the Polaroid lurking among the high-tech 35mm SLRs? Don’t be. The Polaroid SX-70 is a single lens reflex design; it just doesn’t use 35mm film.

What’s good about the Polaroid? The obvious: good color in three minutes. The SX-70 ($220) is also lightweight, compact, and automatic. I personally think the design of the SX-70 lacks something, because it doesn’t have the “feel” of a really topflight camera, but that’s basically irrelevant considering that the virtue of a Polaroid (or Kodak) instant camera is immediacy. It only takes a minute to find out whether you’ve made a decent shot.

You can become an expert photographer with a Polaroid SX-70, but you will have to rely on your eye, not technical wizardry. The camera doesn’t have the versatility or the accessories that 35mm SLRs offer, but a good photographer will not be hampered. How far can you take a Polaroid SX70? All the way to the Museum of Modern Art in New York or the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Both institutions have Polaroid photos in their permanent photographic collections. Not surprisingly, the fully automatic, one-step operation and immediacy of the SX-70 is attracting a lot of hot young photographers, many of whom are mounting well-received exhibits of their work with the camera.

Photo Intelligencer

News from within the camera industry indicates that the above-described big five intend to make a major push aimed at knocking the weaker competitors out of the camera market. This is not necessarily a bad thing, since there are some marginal operators in the business who should have been given the hook a long time ago. The gear-up by the large Japanese companies means that prices on cameras should come down and that you will be able to buy exceptional performance for fewer dollars. Most experts agree that prices will stay down for about two years. During that time, camera design will make some significant advances, as the new breed of 35mm SLRs comes to market. Typically, these cameras will be compact, automatic (with electronic exposure control), and motor driven. Many industry observers believe that it is only a matter of time before motor drive is routinely built into 35mm SLRs as it is into the Polaroid SX-70 (Minolta already makes such a camera).

Electronic exposure control is going to become more prevalent, for a very good reason: it offers the serious amateur a precision that he may have found hard to achieve with the now standard mechanical control. But the main advantage is that it eliminates the gadget fiddling that too often takes the spontaneity out of 35mm photography.

Meanwhile, big-five member Minolta continues to roll on, offering three Minolta 35mm SLR automatics, one for every taste and pocketbook. Of the three, the Minolta XE-7 will probably have the widest appeal. It’s automatic, uses an electronically set shutter, and has a lever that allows you to take multiple exposures easily. The automatic exposure system varies shutter speed steplessly from four seconds to a thousandth of a second. Priced at $340, the Minolta XE-7 has taken off in sales. Minolta’s XK model ($765) is its top-of-the-line automatic, notable because it is the first automatic to have three interchangeable viewfinders—a feature usually seen only on cameras like the Nikon F2 or the Canon F-l,

Minolta is hot in other formats besides 35mm. They have recently followed Canon’s lead by advertising on television, but the product being promoted was not a 35mm SLR, but a 110mm SLR—the Minolta 110 Zoom. This camera ($230) uses the same quick-loading film cassettes as the Kodak Instamatic, but it has better optics because of a 25mm–50mm zoom lens. It is automatic, and is the first 110mm format SLR. It’s a nice investment for someone who wants to get into photography but has no desire to fuss with 35mm.

Another impressive Minolta product, the Minolta spot meter, has also been updated. A spot meter takes a light reading of a very small area, whereas an averaging meter takes a reading of an entire scene. The spot meter allows you to survey a scene with both extreme light and shadow (the most difficult light situation to meter accurately), adjusting the exposure to produce the effect you’re after. The spot meter is an extremely handy accessory, and now Minolta has made it easier to use than before by offering a lighted information readout on its latest model, the Minolta Auto Spot II. Priced at $650, it will not be a common accessory.

Konica, a company that pioneered automatic SLRs, offers its latest model, the Konica Autoreflex TC. The TC is right in line with the new generation of automatics: it’s compact and has an interesting feature that lets the lens vary metering angles of the built-in light meter, supposedly giving you more accurate exposure readings with a wider variety of lenses. The Autoreflex TC is priced under $300 and there’s a selection of thirty lenses available for the basic body.

Hasselblad continues to raise technology and prices to new levels. With a 2¼” x 2¼” format, Hasselblad is highly prized by commercial photographers, who love its resolution. Not a highly portable camera, it is best used in the studio or in other fairly stationary situations. The Hasselblad factory was recently sold to a large Swedish concern because the founder, Dr. Viktor Hasselblad, had no heirs. It is reasonable to expect that the new owners will update the Hasselblad line. First stirrings of new directions came with the introduction of the new Hasselblad 2000-FC, a camera that can make use of either a focal-plane shutter (built into the camera body) or the spring-leaf shutters that traditionally come with Hasselblad lenses. Priced at $1800, it won’t be found in every home. Also new at Hasselblad is the first zoom lens offered by the company, the Schneider Variogon 140mm–280mm lens ($2000). These days, a Hasselblad system costs about the same as a nice, medium-sized car.

You can buy a similar type of camera, the Bronica ETR, for about half what a Hasselblad costs and still have something left over for a roll or two of film. The ETR is Bronica’s solution for people who want a larger format camera but not necessarily a larger format price. The Bronica has a 6cm x 4.5cm format and it’s making a few waves. One reason is the design. The ETR is extremely easy to handle—it has a great feel—and is far more portable than similar models. Bronica also offers a speed grip, which allows you to fire the shutter, advance the film, and cock the shutter with one hand. It’s very fast and very handy on a large-format camera, and makes you wonder why nobody thought of it before. You can get a Bronica with interchangeable backs, finders, screens, and so on, but most people will buy it with a waist-level finder, 75mm lens, and one magazine for 120mm film for a mere $825.

Kodak’s entry into the instant color print camera market was countered by Polaroid’s entry into the instant color movie market. While the two companies continue to dispute ownership of the patents involved in instant color photography, the consumer is being bombarded from both sides. The hottest cameras are Kodak’s The Handle ($40), and Polaroid’s Pronto! ($60) (the exclamation point is part of the name). Unveiled at an April 26 stockholders’ meeting, Polaroid’s instant color movie process was hardly unexpected but amazing nonetheless. With Polavision, which may be on the market by this fall, you slip a film cartridge into the grip-held camera and shoot. The cartridge is developed in less than two minutes flat in a processor/player that looks like a microfilm reader. The price for the outfit will be competitive with a good home movie system. We just wish that Polaroid would adapt the process for 35mm slide film.

The neatest accessory out today—besides the autowinder—is the data back. The data back attaches to or replaces the standard camera back and imprints month, day, and year, together with other information, directly onto the film. Pentax wasted no time in getting a data back into the catalog to go with its new MX series of compact 35mm SLRs. The Pentax version shows month, day, and year, and other settings can show film speed, shutter speed, and aperture. It’s going to be popular with photographers who experiment a lot. It’s reasonable to think that within a few years, the microcomputer technology employed in cameras will make the data back a built-in accessory.

Although Leica makes a fine single lens reflex camera, people do not come to Leica for that design; they come instead for the superb Leica rangefinder, the choice of many top photojournalists, and art and documentary photographers throughout the world—Cartier-Bresson to name only one. The latest, the Leica M4-2 ($1200 with 50mm f2 lens, but with no built-in meter), has the traditional Leica virtues of accuracy, sharpness, portability, and the best construction in the business. Rangefinder cameras are a completely different experience from SLRs, but if you decide to go the rangefinder route, by all means save your money and get a Leica. They last forever and are a joy to own and operate.

Finally, what’s ahead for photography in the foreseeable future? First the bad news: silver, basis of the light-sensitive emulsion that goes on both film and paper, is getting scarcer. Now the good news: a controversial genius named Stanford R. Ovshinsky has invented a type of silverless black-and-white “ovonic memory” film that develops instantly and has the potential to replace conventional microfilm. When asked by the Wall Street Journal whether he could invent an instant color ovonic memory film and camera, Ovshinsky said, “I think it could be done, maybe when I’ve got time, I’ll do it.”

Shop Like a Pro

If there was ever a year to shop for a new 35mm SLR, 1977 is the one, because this year the camera manufacturers have knocked themselves out to put some innovative products on the market. No matter what your requirements, you can find a 35mm SLR that will fit your needs. You hope the price tag will also fit your pocketbook, but the chances are better than even that you can get a good deal, because the market is very competitive. Before you go to the store, here are a few things to think about.

Automatic or manual control

Opt for the automatic. After all, if you don’t want to use the automatic mode, with most models you can just switch it to manual. The advantage of an automatic camera is that it lets you concentrate on the essentials of photography: framing, composition, recognizing the decisive moment. You won’t lose much in the way of versatility, and more and more accessories are becoming available every day for automatic cameras. If you start with an automatic and then decide you need the systems versatility offered by top-of-the-line manuals like the Nikon F2 or Canon F-l, your automatic will become an excellent second camera body.

Aperture or shutter priority

Automatic cameras come with one of two types of light-metering systems. Aperture priority means that you set the aperture and the camera selects the correct shutter speed automatically. Shutter priority systems reverse the process (you set the shutter, the camera selects the aperture). The Nikon EL2, Olympus OM-2, and Pentax ME are all aperture priority cameras; the Canon AE-1 is a shutter priority camera. There’s not enough difference in everyday operation to worry about which offers best performance. Just go with your preference.

Systems or nonsystems camera

The recent trend in camera design has been to produce camera systems instead of isolated models. The systems approach usually means that a manufacturer has designed a basic camera body and then produced a wide range of accessories (interchangeable viewfinders, viewfinder screens, microphotography attachments, remote control, etc.) for it. Systems cameras offer more versatility than an amateur is likely to find uses for, but they can be important for professionals. If you don’t think you’ll generally need more than a good camera body and a few lenses, don’t spend the extra money that’s required to buy a camera with systems capability. On the other hand, specialized photography (like architectural or wildlife photography) may demand the systems approach. Canon, Nikon, Olympus, and Pentax manufacture camera systems.

Compact or full-size camera

It all depends on what feels best to you. Some folks like the light, tight feeling of the compacts. Others prefer the size of the conventional 35mm SLRs like the Nikon EL2. If you have large hands you might have trouble working with a compact. If you have small hands, you might find that a full-size Minolta is a handful. The only way you’ll really know which is best for you is to test a few different types in the camera store. The compact cameras are easier to travel with, and you can also pack more accessories because the basic body is small. The larger 35mm cameras are usually more durable and rugged.

Don’t shop for a name

The most serious mistake you can make is to shop for a name instead of a good piece of equipment. Don’t fall into the trap. Investigate all the major manufacturers’ offerings and don’t neglect the smaller camera companies like Vivitar, Ricoh, Contax, or Yashica. The same is true for lenses. Vivitar and Soligar make excellent lenses at lower prices than the big camera manufacturers.

Check out the controls

At the camera store, you should examine different models in the same price range. Plan on spending about $250 to $600 to get a state-of-the-art camera and a sharp lens. You can buy a new 35mm SLR for as little as $100 or as much as $800, but the best values will be found in the middle ground. Ask the salesperson to point out the important features of each model and explain their purpose and operation. Have him fit all models with the same focal-length lens (a 50mm “normal” lens, for example). Hold each camera up to your eye, at your side, and sling it on a strap over your shoulder. Take a look through the viewfinder and carefully examine the image; it should be sharp, bright, and offer good contrast. Focus the lens; some cameras’ focusing systems will not be as easy for you to use as others. Ask the salesperson how to load it, set the light meter, focus, and set the shutter speed and aperture. Find out how easy it is to switch from automatic to manual. Fire the shutter and try the film advance. If the camera has an autowinder on it, ask about ease of attachment. Find out where the batteries go and how easy they are to load. Remember that with the new breed of 35mm automatics, when the battery goes out, the camera ceases to function as an automatic.

Try changing lenses; they should go on and off with relative ease. Ask about accessories, the prices of different types of lenses, and the warranty—cameras do break. You should also inquire about the camera’s service record.

If the camera doesn’t feel right in your hands, or if you have difficulty either reaching or operating the controls, try another model. It’s very natural to feel fumble-fingered when you first pick up a 35mm SLR, but in less time than you think, you’ll find that the camera will become a part of you.

Make certain that you understand how the built-in light meter works and be sure that the metering information is easy to read and interpret. Some of the modern 35mm cameras display a lighted readout of shutter speed and lens aperture in the viewfinder, along with the meter reading.

After you’ve purchased your camera, take it home, load it, and shoot a roll or two of film. Check the photos or slides for light leaks (a lightening of the image or streaks of light across the film), proper exposure, and accurate focusing. If you’ve bought an automatic, exposure should be consistently good from frame to frame. If the slides or prints show trouble, take the camera back to the store immediately and let them examine it for you.

Purchase sensible accessories

The professional photographer buys the best equipment available for jobs that he does on a continuing basis. He does not buy a 500mm telephoto lens since he won’t use it more than once or twice a year. When he needs one, he rents it. Follow the pro’s example. Buy the best when you buy accessories that you’re going to use a lot, like a tripod, or several lenses. A basic 35mm system should include a camera with normal lens (50mm or 55mm), wide-angle lens (28mm or 35mm), and either a telephoto lens (135mm) or zoom (75mm–205mm). You should also consider buying a tripod and cable release, especially if you want to take long exposures. You’ll also need a place to keep your camera. Halliburton makes a watertight aluminum camera case that many photographers like and which is the best on the market. For location work, a hard case like the Halliburton will prove awkward, so you may want a shoulder bag. I use an Orvis fishing tackle bag (it has a solid bottom, a wide shoulder strap with leather pad, enough room for two bodies, four lenses, film, and accessories). Camera stores offer similar bags at reasonable prices. Sometimes it’s wise to get a bag that’s small since you will then be forced to travel light.

Camera maintenance

You must keep your camera and its lenses in good condition, so purchase lens cleaning fluid, pressurized air, and a small soft brush. Those accessories will help keep your camera in good working condition, and by doing your own routine care, you will acquire a feel for the construction of your camera; this in turn should increase your knowledge of its capabilities.

- More About:

- Art

- TM Classics

- Longreads