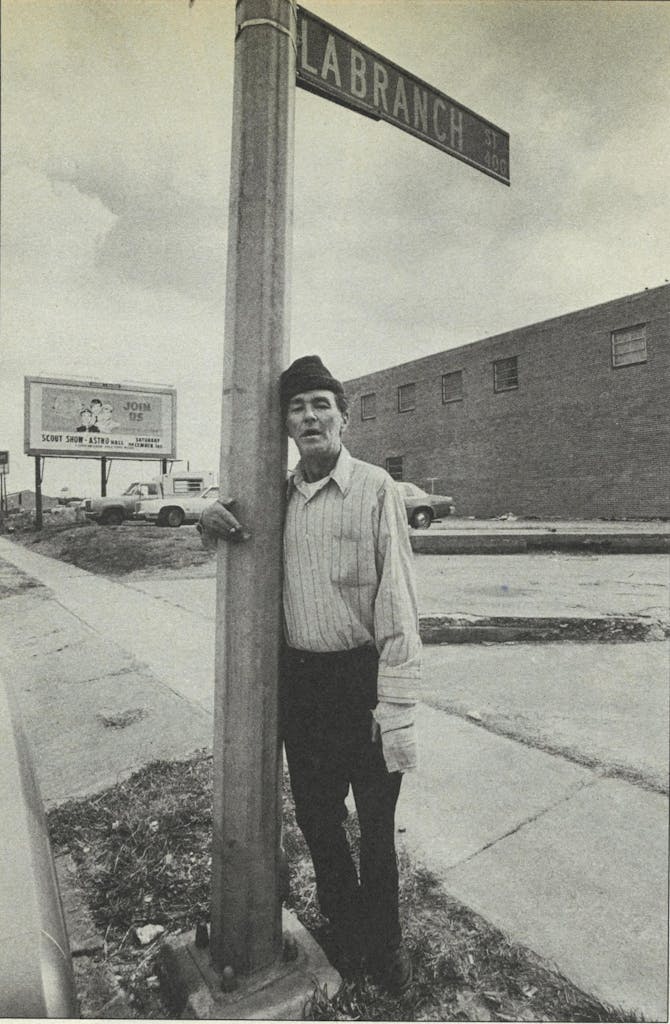

The Star of Hope Mission is a United Way agency dedicated to the proposition that winos must be saved. It sits in the 400 block of LaBranch, on the crumbling northeast edge of Houston’s business district—just paces away from a defunct blood bank where down-and-outers once traded their blood for money. Between the mission and the Greyhound terminal two blocks away is nothing but parking lots and empty buildings. The DeGeorge Hotel stands across the street from the mission. Its lobby now smells of mold, and its window screens are plugged with hoary dust and street film. The hotel is in every way a part of its dreary dead-end neighborhood, but the Star of Hope is a wholesome refuge from all this grimy decay, a USO for winos.

On afternoons when it is cold, drunks who don’t have a dime for the proverbial cup of coffee can go inside the Star of Hope and sit or doze on the hard wood seats of its auditorium. Men without a fixed address can receive mail in care of the mission, and those who believe their souls are lost can always find religious succor there. Every day at supper the Star of Hope feeds more than a hundred unfortunates and, in exchange for their sitting through a sermon, beds them down in its dormitory upstairs.

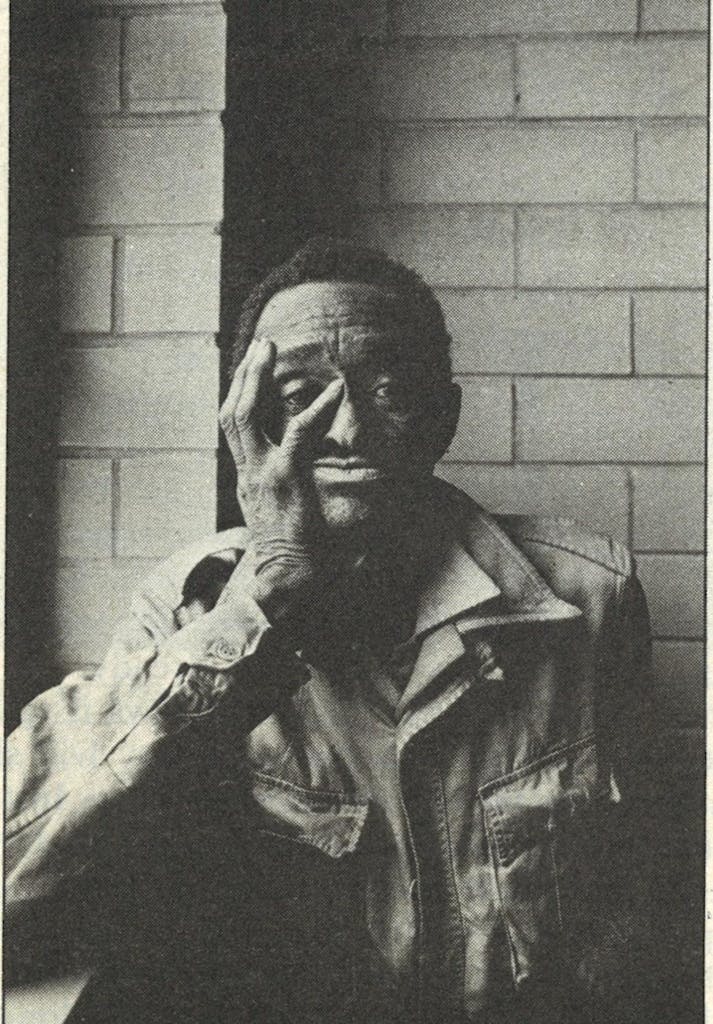

All large American cities have a skid row, an enclave for those men commonly called “down on their luck.” The term skid row comes from Seattle’s skid road, where fifty years ago casual laborers, when they were sober, dragged logs to the sawmills down “skids” of greased timber. New York has the Bowery, New Orleans has Camp Street, San Francisco has Sixth, all of which have been skid-row neighborhoods for generations. Periods of economic and social dislocation swell skid rows with the human material wasted or idled by crises. During the Depression thousands of ordinary workingmen became hobos simply to survive, and during the sixties thousands of young people stumbled into wino lairs in a psychedelic haze sometimes laced with cheap wine. But the normalcy of the seventies has reduced all skid rows to vestiges of what they once were, and in Houston, the district has shrunk to almost nothing. There are no streets lined with flophouses, and there is only one shop that makes nickel-and-dime loans on the sorts of tawdry personal possessions winos are likely to have—pocketknives, coats and old shoes. Houston’s prosperity and the tenor of the decade have also reduced the city’s wino population to the hard core, a group of about a thousand middle-aged men from Protestant, hard-labor backgrounds, often with petty criminal records and petty criminal pursuits. Blacks and whites are about evenly divided, but there are few Mexican-Americans, presumably because the Latin family structure takes care of its own. Women are rare, as are men younger than forty, but neither is as rare as a teetotaler.

During the muggy months of summer, about half of the city’s winos go north, coming back when New York, Chicago, Detroit and Minneapolis grow cold. Though Houston’s skid row is not a favored haunt, it will not disappear entirely, so long as the city is an important rail connection, for winos still hop freights; nor will it disappear so long as Houston has a veterans hospital, for some winos use VA hospitals as vacation spas. Most have multiple health problems resulting from alcoholism, if not from war injuries. Many go to the VA to dry out, or simply to rest, eat well and get personal attention. Few stay long, since drinking is not allowed on the wards. Those winos who are not veterans tend to hover around the run-down districts in the cities of Louisiana and California, which distribute public health benefits more freely than Texas does.

In Houston, the Star of Hope is practically the only place where a wino can get a free supper and a free bunk. There is another mission with sleeping quarters, the Harbor Light, up on North Main, well beyond the center of skid row. Operated by the Salvation Army, the Harbor Light gives men two nights of free lodging a year, but afterwards charges $3.50 a night, more than most of them can spare.

About 5:30 the supper line forms inside the Star of Hope, and I get in with the others. The line begins in the auditorium and extends through the foyer into a waiting room with about fifty folding chairs inside. As we file from the foyer into the waiting room, a freshly scrubbed little man in a frayed but starched white shirt hands us tiny yellow leaflets. The flyers, from the Pilgrim Tract Society, ask, “Which way are YOU headed?” Two fingers point out from the big question mark, one right toward “Hell,” the other left to “Heaven.” Everyone here is headed only to supper, just like yesterday and the day before, when we were also handed salvation leaflets. Just as before, everyone stuffs the tracts into pockets without reading them. But the men can’t ignore another warning in the foyer, a life-size cutout of a man trapped inside a whiskey bottle. The winos see that figure every evening, and more than one of them has told me that he is the man inside the bottle.

Supper at the Star of Hope is vegetable soup from a half-filled stainless steel bowl and two iced doughnuts, both nearly hard enough to use as cudgels. We sit in groups of ten around five Formica-topped tables in the room. Only one voice speaks, that of a young “traveler,” or drifter, a white youth who has come to Houston on his way to Miami. He is boasting that when he gets to Miami, prostitutes will support him. But no one speaks to him, because winos despise young travelers, whom they believe should be out working on steady jobs. No one looks his way, either, for winos do not look at anyone while they eat. They do not normally chat over food at the Star of Hope, either. Were it not for the traveler’s monologue, the only sounds would be grunts, coughs and the shuffling of feet.

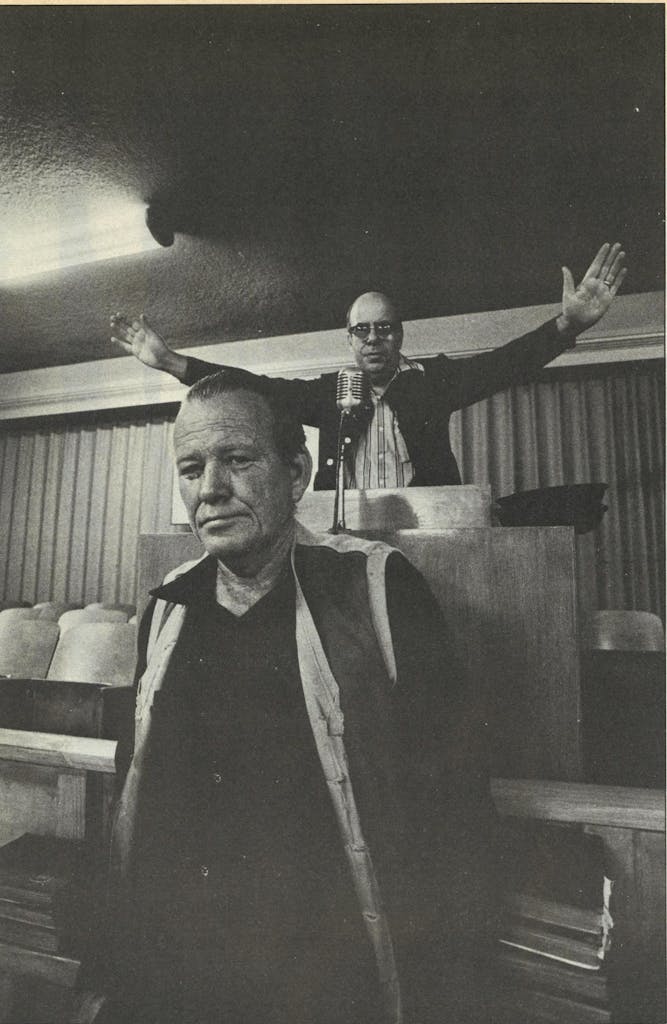

Brother Bob is in charge of the mission tonight. He’s a plump, balding, rosy-cheeked, fastidious man about 45, with thick black-rimmed spectacles pushed tightly up against his eyelashes. Today he is wearing a navy blue double-knit suit, a sleek tie of the same color and a fluorescent flamingo red polished cotton shirt. Brother Bob sashays back and forth from the foyer to the waiting room to the dining room, chatting with mission staffers in the cheerful voice of a priest. But pretty soon he steps into the dining room and barks at the boasting traveler, “Why don’t you cut out that jabbering and get some eating done?” Eating is apparently a job to get done, because Bob goes home immediately after supper.

Seconds later, for no apparent reason, an elderly black throws a doughnut on the floor. It makes a thud. One of the burly guys on the kitchen crew hollers for Bob. “He’s going to call the cops on that guy,” the wino next to me mutters. A few minutes later two cops come in, and Bob points to the doughnut still on the floor. But the doughnut hurler has slipped out. Brother Bob assures the officers that he’ll call without hesitation if there’s trouble again. They nod and try to keep straight faces, pretending to take the crime seriously. But they don’t take any notes and nobody is questioned. After the cops go out, the man from the kitchen crew picks up the doughnut and lobs it into a garbage pail.

By six o’clock I’m back out on the sidewalk. The doors close at seven for the worship service, and in order to sleep at the mission, you’ve got to attend. Between supper and salvation time, the men smoke a few cigarettes and go around the corners of the building in twos and threes to take last-minute swigs from their bottles. If Brother Bob or other mission men catch them, they’ll be turned away at the door.

At night the Star of Hope’s attendants take all your clothes, give you a towel and send you to the showers. You sleep in the buff in a barrackslike setting with a hundred other men, some of whom keep you awake with intermittent fits of gurgling, wheezing and retching. Almost all night there are men making trips past your bunk on the way down to the bathroom for diarrhea and spitting up sputum.

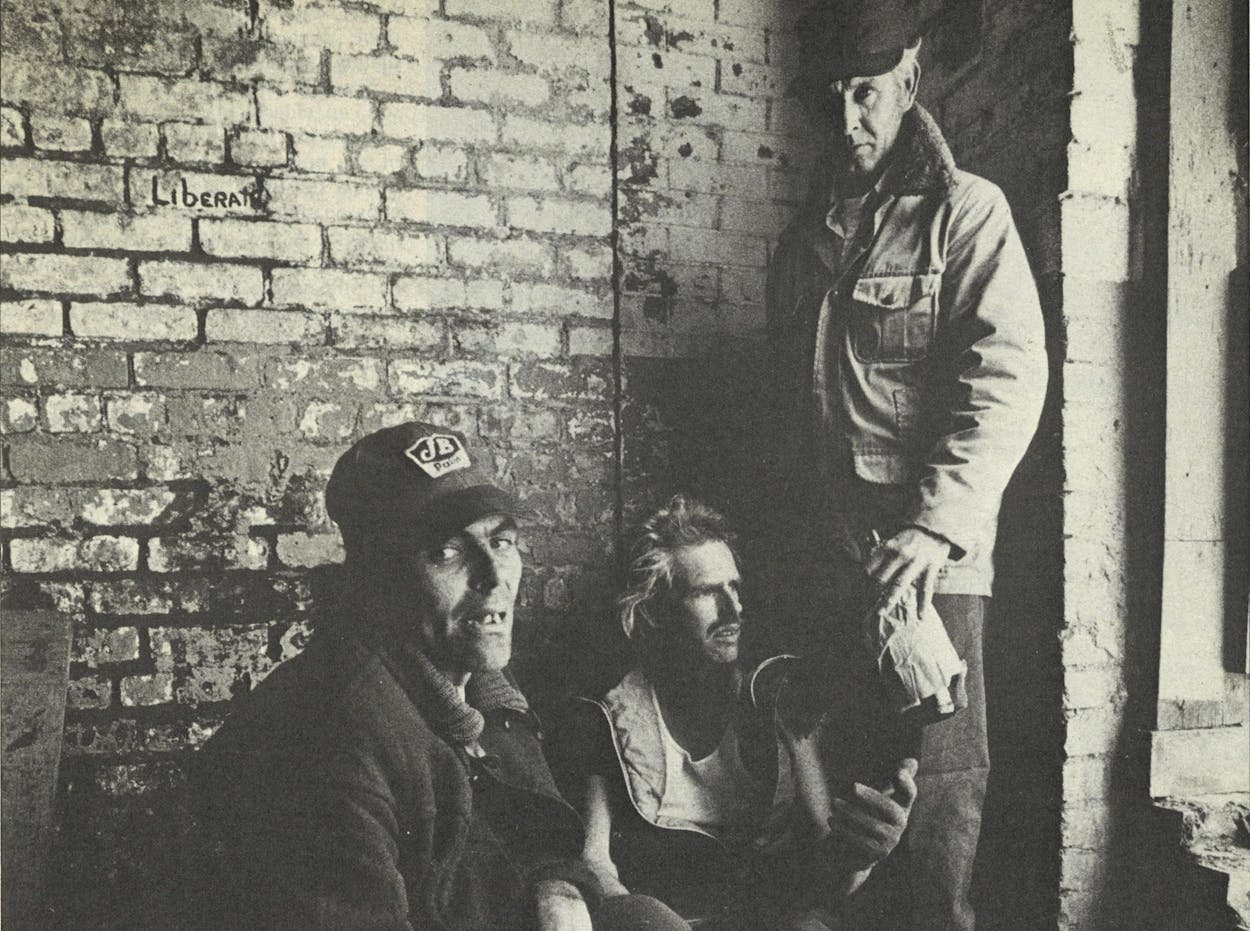

A group of winos forms across the street every night at this time, a group whose general aim is to find unsupervised sleeping quarters where they can continue binges begun by day. Vacant buildings in the district are favorite haunts, but tonight several of the men are hesitant. Last week somebody set fire to an abandoned parking garage where three winos were sleeping and one of them died in the blaze. The rumor, or the popular fear, is that there is a sadistic arsonist on the loose.

Joining in the talk is a wino known in the neighborhood as the Veteran. The Veteran, who says he’s not afraid of any lunatic with matches, is a lanky, pale man, with graying, greasy blond hair combed back into ducktails. What appears to be a knife scar runs at an angle across one cheek. Like almost all other seasoned street drunks, the Veteran wears a suit coat, not because he thinks it makes him look like a professional man, but because he gets his clothing at missions like the Star of Hope, where old clothes are free. Donors rarely part with warm jackets or overcoats, but out-of-fashion suits are plentiful. Winos, for their part, do not wash clothes. Instead, they go back to the missions to get new castoffs. Every morning there is a clothing issue at the Star of Hope, and some men stay there at night just to be present.

Standing beside the Veteran is a smaller man with wavy hair and a week’s stubble on his face. He wears a suit coat with narrow lapels. Since the two are drinking with relative abandon, I assume they don’t plan to sleep at the mission. They hit me up for cigarettes, and when I oblige, they introduce themselves.

The Veteran turns toward his mate. “This buddy here, I met him in Virginia during the apple harvest. We come down here together. I call him ol’ Merle Haggard, ’cause he can sing just like ol’ Merle.” He points an index finger in the air. “Maybe better.”

I half expect “Merle” to break out singing, like in a musical. Instead, he takes a step backward and looks up at the Veteran, glancing quickly at me as he begins to do the honors in exchange.

“This here ol’ buddy, he was the second most highest decorated man in Tennessee in—what war, buddy?”

“The Second World War, Pacific Campaign.”

“Yeah, in the Army, the second most highest decorated man in Tennessee. How about that for you?” Even when a man doesn’t have cigarettes, his laurels carry him through.

Merle begins to tell how he, too, served in the Army, nineteen months in Korea. But the Veteran interrupts. “Man, I was in the Army twenty-six whole damn years. I get a check every month from the VA, and I can get in any hospital I want because, see, my trouble is service connected.” He lifts up his shirt, Lyndon Johnson-style, and points to a deep, round scar flanked by straight incision lines running up and down.

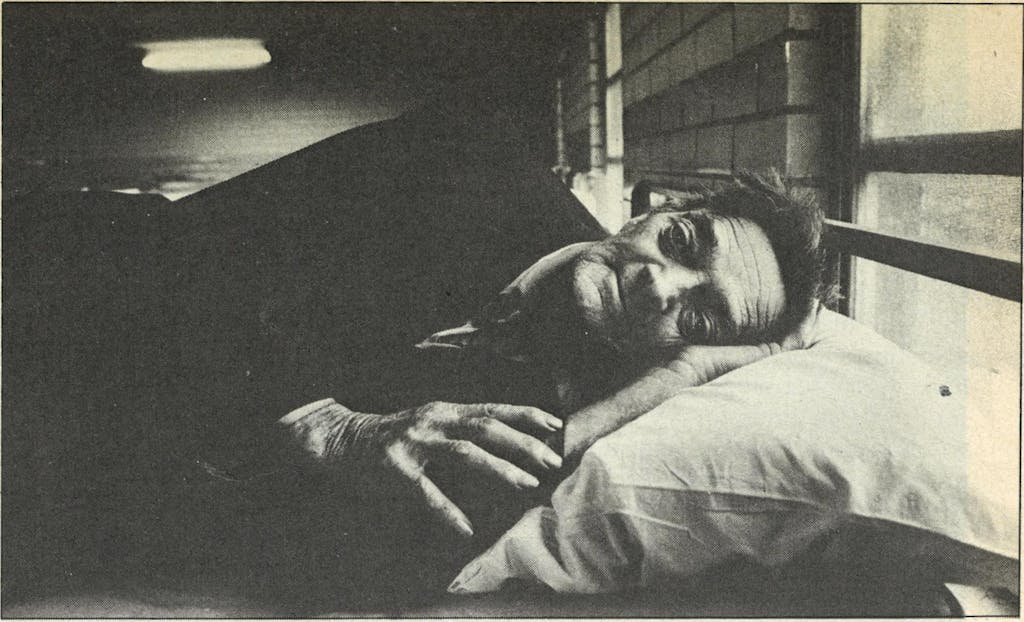

All winos look down on all other winos. Merle and the Veteran, as military men, consider themselves especially superior to mission winos, who are domesticated souls tolerant of abuse and herding. Merle and the Veteran prefer a billet on the streets. But tonight, shame though it is, Merle is going inside the Star of Hope. There’s a button on the dormitory wall, surrounded by a sign that says, “If sick ring bell,” and Merle wants to stay near that button. He’s begun to cough up blood and worries that he may need a doctor during the night.

The Veteran has spotted a truck to sleep in, and he volunteers to take me along instead of Merle, who must soon go inside the mission. When Merle leaves, the Veteran and I walk three blocks north, into the warehouse district where the truck is parked, its window opened just a crack, the way the Veteran set it earlier in the day. He reaches through the window to open the door and we climb into the cab. Since the Veteran found the truck, he has rights to the seat; I get to sleep on the floor, the gearshift lever on one side of me, the transmission hump below. Only a worn rubber mat covers the metal floorboard.

We lie in the cab a couple of hours, while the Veteran sips on a half-pint of Four Roses whiskey and tells me war stories. Iwo Jima, Guadalcanal, even Bataan—he says he was at them all. “The second most highest decorated man in Tennessee,” he slurs, just before passing out. I reach up to his suit coat, feel around until I find the bottle cap, and screw it onto the bottle. It is still locked in his hand.

Propped on my elbow, I lie smoking, savoring our independence from the mission. Two hours later my toes are tingling with a chill that goes up past my ankles. A cold front has moved in bringing a record low, the newspapers say the next day. The Veteran is sleeping uneasily. He squirms, his feet pushing hard against the door of the cab. He tries to turn over, and lets the bottle slip. It hits the floor with a clunk, and he wakes up. I see him frowning, trying to figure out where his bottle went. After I hand it back to him, he sits up a little, raises his neck, twists off the cap, and sucks down a shot.

“Man, it’s cold as hell,” I complain.

“We’ll fix that up,” the Veteran says. “Ain’t nothing an old Army man can’t do.”

He sits up erect, nearly awake and seemingly sober. After fumbling through his coat, he comes up with a pocketknife, which he uses to cut the truck’s three ignition wires. He shoves the gearshift into neutral, twists the ends of two wires together, then touches them with the tip of the third. The engine cranks up.

“Come on boy, give it the gas.”

I pump the accelerator pedal with both hands. The motor starts running, sending a smooth vibration through the metal beneath me. “You keep it running till the motor warms up. Then disconnect those wires. If you get cold again, do what you saw me do.” Then the Veteran flips a switch on the dashboard—the heater control—and falls back on the seat. I keep my hand on the gas for nearly an hour before I am warm and sleep overtakes me.

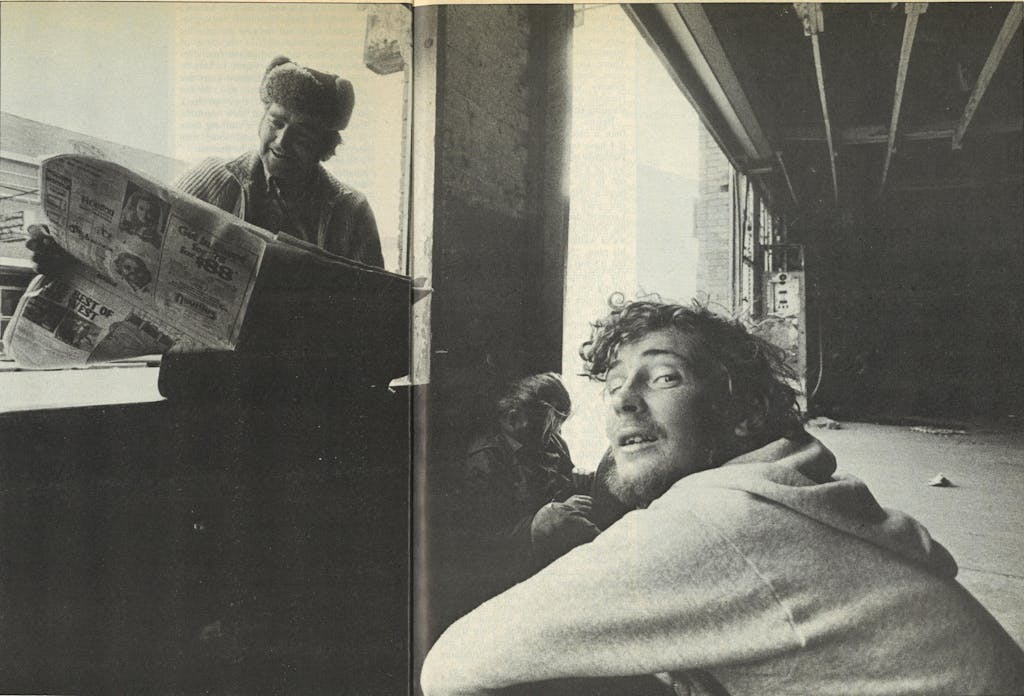

The clatter and rumble of the warehouse district wakes me about 6 a.m., and I shake the Veteran to his senses. We slip out of the truck, afraid of being seen, and hustle down the street towards the wino perimeter. Everyone is already on the sidewalks; the mission throws its guests out at 5:30, in the hope they will show up at the labor pools on time. Instead, most of the men pass around the bottles they stashed away the night before.

Merle is sitting on the sidewalk with a clump of men. Clean-shaven and wearing a fresh shirt, he looks longingly up from the sidewalk as the Veteran licks the last drops from last night’s half-pint of whiskey. The Veteran pretends an apology. “Well, ol’ buddy, if you’d said something I’d have given you a taste.” Merle says he doesn’t feel like drinking yet, anyway. Last night he spit up blood twice and this morning his stomach is burning. “What you need for that problem is a little bit of that creme de cacao. That stuff won’t burn your belly at all,” the Veteran advises. Then he pulls out his upper dentures and shows them around. The plate is made of white gold. “Ol’ buddy, we’ll go put this in hock in a little while and then we’ll get us some of that creme de cacao.” The Veteran claims he’s been loaned as much as $40 for his teeth.

The corner of Preston and LaBranch, in the shadow of the DeGeorge and just across the street from the Star of Hope, is an open market—sometimes clandestine—labor hiring hall. A roofer stops his pickup to offer $2.50 an hour for an assistant. The winos demur this morning; it’s too cold to go up above ground level, they say. A landlord asks for someone to sweep out a building at $2 an hour; one of the younger winos, a black with an earring, takes the offer on condition that the job last no longer than four hours. Labor seekers are plentiful, but winos will not stoop to work under just any conditions. “Put up insulation? Man, you know that stuff makes you itch,” the Veteran drawls at a labor prospector. After he has spoken, no one else will take the opportunity, either: being above some jobs is a matter of pride.

About nine o’clock, Merle, the Veteran and I are still sitting on our haunches with our backs against the sidewall of the DeGeorge. The Veteran has forgotten for the moment his offer to pawn his teeth. He and Merle are arguing about wages they received for apple picking—this time they say it was in North Carolina, not Virginia. A frail, amber-skinned man walks by, his Afro flattened-out in back and dusty from sleeping on the ground. The Veteran calls him back. “Look, Leonard, my hands are shaking,” he says, stretching out his thin, bleached hands, which indeed are trembling. Leonard throws a glance behind him to see that no one is looking. Then he motions us to follow him around the corner, to the front of the DeGeorge, where the other winos won’t see. When we all sit down there, he pulls a half-pint of muscatel out of his gabardine suit coat and passes the bottle to the Veteran. After taking a swig, the Veteran passes it over to Merle, who drinks down a sip despite his stomach condition.

A paddy wagon turns the corner at the far end of the block. “Hide the bottle behind your jacket,” the Veteran warns, passing it over to me. No one tells me why I must hide the bottle; it’s presumed I already know. I stick it in the small of my back as the cop rolls up in front. He eyes us casually. Nobody speaks. “You boys better move on. The owner of this building complains when y’all hang out in front,” he says, as if from sympathy with our condition. He doesn’t get out of the van to search us for liquor or anything else; apparently there is no status to be gained by harassing winos. “Yes sir, we’re just here for a minute,” Leonard replies. As we go back around the corner, Leonard philosophizes: “Man, I don’t know about y’all, but I’m a not-guilty man myself. I don’t give a damn what they charge me with, I’m not guilty. Am I drunk? Now how are they going to prove that?” Leonard is right: if he’s drunk, I’m holding the physical evidence, not him.

Around the corner, Leonard and I sit down with the other men gathered there, but Merle and the Veteran go off to pawn the Veteran’s teeth, or so they say. I spend a few minutes sizing up Leonard. He’s clad for the weather, as I wish I was. Under his scruffy brown suit coat he wears two shirts. The one on the outside is a dingy white, and the one underneath appears to be one of those happy Hawaiian prints vacationers like to sport. Leonard has on two pairs of pants, too. On top, a red-white-and-blue double knit, and sticking out below the cuffs, a brown-and-black double knit. But his left shoe has a hole in the side and Leonard isn’t wearing socks.

I gripe about the cold, and Leonard takes over. “Man, this town is screwed up. I’m going to California, yes sir.” A man about sixty who is called the Rail King is sitting to Leonard’s right on an orange cotton sleeping bag. He draws gently on a pipe with a profile like his own: long-stemmed and ebony black. Unlike other winos, King’s dress is nearly collegiate and practically new. His nature shoes are unscuffed, his gray suit pants are sharply creased, and he wears a denim jacket with glistening white fleece lining. Long johns creep out from under his pants legs and over the bottom of his fluffy flannel shirt. There’s a blue stocking cap over his knotty gray hair, and it, too, is new. Though such prosperity is remarkable among winos, personal questions are equated with prying in wino society; so I can’t ask him about his good fortune. Instead I listen as Rail King and Leonard extol the welfare benefits of San Francisco, San Jose and Los Angeles. When I inquire how they get to California and back, four brown eyes stare up incredulously. “Man, we ain’t just winos, like you think. We are railroad tramps,” blurts out the King. I tell them I’d like to go to California and Leonard says he’ll take me—now, if I want. I agree and without a word he stands up and starts moving down the street. I jump up to tag along, and Rail King hollers from behind, “Better catch a bus to the Liberty yards.”

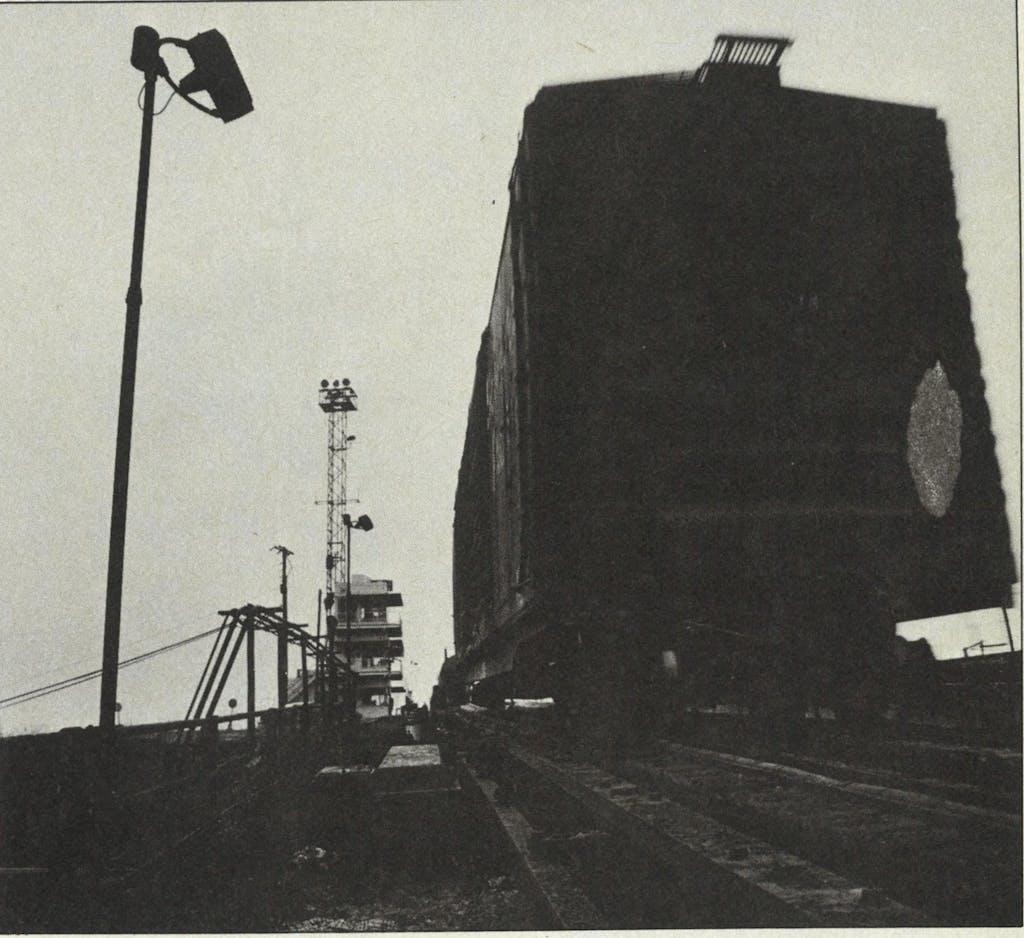

The Liberty yards (Englewood Yard on Liberty Road), near the Kashmere Garden residential district on Houston’s northeast side, are a switching point for the Southern Pacific line. There freight cars are made up into trains that are dispatched to points east and west. There, too, the Missouri Pacific tracks cross, coming in from the north. The Liberty yards are the place where freights can be hopped while they’re standing still.

Before we have walked little more than a block, Leonard wants to know if I have bus fare. I give him 55 cents. He leads me through the wooden doorway of a downtown shanty, which turns out to be a wineshop. Inside Leonard buys a fifth of Thunderbird. “Now we can walk out to the Liberty yards,” Leonard declares, screwing the top off his bottle of Thunderbird. But before we’ve walked three blocks, he’s changed his plan. “Now I can walk it, you see, but it’s too damned far to walk. I don’t like walking that far.” But instead of taking me toward the rail yards Leonard guides me back to LaBranch and Preston, where he is soon passing the bottle around.

Rail King shows no surprise at seeing us back again. Like the others, he wants to get his share of the bottle we’ve brought. By the time it’s empty, lunchtime has come. Around noon, bands of wino friends drift toward the Loaves and Fishes Mission—which they call Fish and Loaves—a storefront soup line at Congress and Chartres. Rail King goes part of the way with our group, then without a word fades off into the warehouse district.

More than a hundred men are crowded around long wooden tables at Fish and Loaves. On one side of the low-ceilinged dining room, a dozen plump, middle-aged women are preparing food for the flock, chattering as they work. These women from all appearances might be undergarment clerks at a department store or bookkeepers in the credit department, but most are housewives from the Catholic congregations that support the mission’s work. They are volunteers, and their spirit is overflowing. They stroke us on the back or shoulders—even pat our heads—as they place brimming plastic bowls before us.

On the sidewalk after Leonard and I have finished eating, the Veteran runs up, panting and excited. “Man, we’ve stole us a case of Campbell’s cream of mushroom soup!”

“But there’s meat in the soup inside,” I point out, noting that he still has his dentures in place. The old soldier scowls—have I forgotten his independence? He pushes past us and goes into Fish and Loaves, in a hurry to scavenge or con a can opener from the good ladies inside.

Once again Leonard decides to head for the Liberty yards. It takes him more than an hour to find the corner for the bus. Finally we find it and get on. After a ten-minute ride, I see the yards. Several dozen tracks entwine across a distance of about three miles, creating a maze of steel rivulets whose patterns are understood only by trainmen and tramps. Short strings of cars are pushed back and forth, coupled and uncoupled. Diesel horns blow and the air smells of exhaust fumes and creosote.

A westbound freight is pulling out slowly. Leonard says we shouldn’t try to catch it. “It hasn’t got enough power,” he tells me—and I get my first lesson in hobo idiom. “Power” refers to locomotives. The train we see has only one locomotive, and Leonard says it takes three or four to pull a freight to California.

Before he disappeared, Rail King told us to find the quonset pedestrian tunnel that juts out into Liberty Road and go down through it into the train yard. We find the tunnel, walk through it, and come into daylight on the other side, inside the yard. On our left stands a steel shed and a huge vented metal heater, used by railroad men who work outside. We go up to the heater to warm ourselves, and after a minute, Leonard steps into the shed to ask questions of the dispatcher who works there.

“Say, man, can you tell us what time a train will be going out to California?”

The dispatcher, a white man about fifty, grumbles at first, but finally says, “Come back about ten o’clock. We might have a train leaving for out west,” he growls, turning his back to Leonard.

Company regulations say that railroad men are not to cooperate with tramps, and I am afraid that the dispatcher will pick up the phone receiver on his desk and report us. But as we walk away, Leonard tells me that there’s no need to worry.

“Look man, at night there are more tramps out in these yards than railroad men. If they didn’t help us we’d get even. Why, we could roll one of them and be gone so quick they’d never know who did it.”

Furthermore, the division of labor in the rail yards works to our advantage. The Southern Pacific has hired detectives, called “railroad dicks,” whose job is keeping the cars safe from pilferers and winos. Since security is a specialized function, dispatchers, engineers and brakemen don’t concern themselves with policing the yards and, generally speaking, tolerate winos.

Leonard and I go down into the tunnel again, and as we come up, he says he’s got a plan for spending the afternoon: we’ll bum money for a bottle.

I give Leonard the thirty cents left over from our bus fare, and with thirty cents that he panhandles, Leonard has enough for a half-pint. We walk several blocks down to a supermarket just off Liberty Road.

Leonard is afraid to go inside because he sees a security guard, so I volunteer. Merchants in respectable neighborhoods don’t appreciate wino customers. The sight of them is enough to frighten and offend their better clientele. Winos are shoplifters, too. When a wino goes into an ordinary store, as often as not eagle-eyed employees follow him around, guarding the merchandise. And sometimes, when winos come up to the checkout line, cashiers refuse to sell to them. But there are no half-pints: these are sold only in skid-row stores. The cheapest fifth costs $1.19.

Back outside, I find Leonard trying to make conversation with a curly-haired, white wino who has drifted up from the tracks and is slumped against one of the plate-glass windows by the market’s doorways. Both Leonard and I have seen him down at the mission. But he can’t make out who we are, and his responses to our questions are unintelligible. Though he’s on the brink of oblivion, he does understand Leonard’s pitch for wine money. Reaching ever so slowly and with apparent difficulty, he pulls two nickels out of his suit-coat pockets. He holds them in his hand, palm up, for he cannot reach out to hand them to us. Leonard takes the money and then collars a black in a postal carrier’s uniform. From him he gets the balance of funds for the new bottle. I go inside to make the purchase. When I come back sidewalk the wino’s knees have buckled. He is an insensate puddle now and doesn’t hear Leonard’s invitation to drink. We walk back toward the Liberty yards. On the way I ask Leonard what will become of the man and he says, “Ah, the paddy wagon will probably get him.”

Leonard is soon high enough to talk about his life. He is originally from Picayune, Mississippi, but his last home was Lufkin, where he worked as a carpenter’s helper and lived with a woman who was all right—when she wasn’t lecturing him about the evils of drinking. Leonard tired of her sermons and left Lufkin, as he had earlier left the Army and Picayune, where his wife and children are still waiting for his return. From Lufkin Leonard drifted to New Orleans, which he liked. But “that hippie judge, Eddie Sapir,” sentenced him to sixty days in jail, and when Leonard got out, he swore not to return. From New Orleans he went to San Francisco, which was comfortable until he quarreled at knifepoint with a wino neighbor in a skid-row welfare hotel. Leonard ran from the warrant that was issued, but now—two months later—he believes he can safely go back; his enemies have probably moved elsewhere, too.

Leonard’s mood is rising, and soon he brags that, right now, he’s afraid of only two things in the whole world: eastbound freights and “riding the hump.” Eastbound trains might carry him back to New Orleans, where Judge Sapir presided. The hump is a manmade hill in the Liberty yards. Freights are pulled to the top of it to be broken up and rearranged. Empty cars are uncoupled there and sent rolling down the hump to a collecting yard below. When your boxcar hits the line of cars already in the collecting yard, the impact can hurl you to the floor and send you sliding to the other side of the car, where you fall down dazed. If you’re asleep or lying down, the crash can throw you hard enough to rattle your backbone. Leonard says he’s never ridden the hump, but a buddy of his, Alton, is in a veterans hospital tonight because he fell asleep on a freight that did. “Man, they’ve had Alton in traction for nearly two months now. They had to take him out of this train yard in an ambulance.”

Leonard now declares that a smart tramp doesn’t trust the advice railroad men give; instead, he picks his trains himself. California trains are easy to spot. They are loaded with auto transports, and they don’t carry many empty boxcars. In a few minutes, Leonard has found a train that he is convinced is a California train, and we begin looking for “opens.” An “open” is an empty boxcar with both doors open, not just one. Leonard says tramps will not hop onto boxcars with only one door open—“What happens if that one open door goes shut on you?” When we find an open, we crawl in. Straw packing litters the floor and pieces of scrap in the straw indicate that the car was probably last used to haul fiberboard.

About five o’clock, a mighty jolt hits our car, and then the train starts rolling, going east. Leonard is worried because the hump is to our east. I look out the south door and there it is. Off to one side, cars by ones and twos are rolling soundlessly down an incline. It is an eerie sight, because nothing keeps the boxcars from jumping the track as they round a corner on their way down. I can’t see the collecting yard, but I can hear loud shrieking and banging coming from there.

Leonard stands up in fright, and grabs hard at the doorjamb beside me as he leans out. The train moves on towards the hump, going up. We pass on top of it, then go down the east side, the side from which trains approach it for breakdown. Leonard says that we had better jump soon. The train slows, and I leap out, jogging alongside. Leonard passes me his bottle, then jumps down to join me. “Man, I’m glad you were here. I’d sure hate to lose my bottle on account of that damn hump,” he pants.

We walk perhaps half a mile back into the train yard. Leonard picks another “California train” and we find another empty car. By evening the cold is unbearable. We jump out of our car and scramble through the spaces between tankers on six or seven tracks to our south, finally sighting the lights of the booth we visited earlier in the day. I race for the heater, take my boots off and poke my socks almost into the fire.

Several other men arrive, three white brakemen and the Rail King. “Man, I knew I’d run into y’all out here,” he hollers. He piles his sleeping bag on a bench with a white shopping sack from Weingarten’s. Rail King tells me to open the sack and take anything I want. Inside, there is fried chicken from Church’s, a fifth of wine, a gallon of water, pineapple juice, cheese and lunchmeat—a hobo’s horn of plenty. Again I wonder, without asking, how he came by it all. The King takes three dollar bills out of his pockets and waves them in Leonard’s face. Leonard, apparently as part of a ritual, shows King two bills he has that a railroad man gave him earlier. I keep my hands in my pockets. The two men turn toward me and, believing that I have nothing, swear that from now on, it’s share and share alike.

One of the brakemen goes into the Teletype booth and returns to tell us that if we’ll count fifteen cars back from the west end of track number 6, we’ll find an empty D&RGW boxcar that is to leave for California as part of the Southern Pacific train at 11:30. About eleven o’clock, we traipse out to what we believe is track number 6 and go fifteen cars back. There is our D&RGW. Rail King tells me the letters stand for “Denver and Rio Grande Western,” a line headquartered, he says, in Denver, Colorado.

Whatever its origin, ours is anything but a choice car. There is a residue of carbon black about two inches thick on both ends of it. I climb into half a dozen empty boxcars on other tracks, and drag out sheets of leftover cardboard, which we lay on top of the gritty black pile. Road King, noticing that neither Leonard nor I have blankets, tells me to go find a sheet of polyethylene. The only one I can find is covered with a white powder I can’t identify. Leonard won’t lie down under it. “I don’t like that plastic stuff, man. It makes you sweat, and the sweat gets frozen when you’re on the road.” But we aren’t sweating now. The chill is intense.

Leonard lies down with his head pointing west. Rail King reprimands him. “Man, you sleep like that and if they run us over the hump, you’ll break your neck when we hit.” He orders Leonard to lie down in a north-south direction. Leonard tries to get up, but he can’t. I raise him up by the arms, and he manages to shift into a sleeping position. Then he mumbles something about his bottle; he has left it behind. I hand it over to him, and he goes off to sleep, cuddling it in his arms like an infant cuddles his feeder.

Rail King lights a match and tells me to dig out his bottle. Thunderbird again. But Rail King is a gentleman tramp; he doesn’t drink it straight. Instead, he has me pour pineapple juice down the neck. Then he offers me a taste. The mix has worked; Thunderbird’s bite is gone, though I still get shivers as my swig goes down.

Rail King says he’s from Detroit and has a master’s degree in sociology from the University of Chicago. Along with this goes a tale about how he walked off an administrative job with the city of Philadelphia one day at noon when he heard a train whistle blow. “I just had to try it out, this tramping thing. It was the mystery that got me,” he claims. I ask him if he ever knew a guy named Talcott Parsons in Philadelphia, but he doesn’t know. When I mention Max Weber he brightens up. “Isn’t he a fence in the garment district in New York?” Now, together in the boxcar, I feel we’re friends enough to ask where he got his money. “I had a little light creepin’ to do,” he whispers.

“You mean you got a short job?”

“No, man, I boosted some things,” he says, quite plainly irritated by my ignorance. But I’m still lost in a net of slang, and I ask for clarification. “Man, I stole some stuff and sold it. I liberated a couple of things.”

King also has war stories to tell, including those about Frauleins who jumped into sleeping bags with him during the Battle of the Bulge. He claims that he won the Distinguished Service Cross by single-handedly gunning down fifty Germans, three horses and two cows on the Rhine one night. He also tells how, when he was recalled during the Korean war, his wife slept directly under a fan at her home in Detroit and, because of that, had a fatal stroke. “The lady never left me alone while she lived. Even when I went to shoot pool, she was always there, hanging on my elbow. She gave me two beautiful daughters and a good son, and then she left us for heaven.”

King couldn’t accept her death. He told himself that she would return, that she wasn’t dead but had merely gone off to visit her parents. He spent almost a year in his living room, listening, waiting for her footsteps on the front porch. When he lost hope, King began drinking and riding the freights. This story I believe.

King’s children are adults now, and he visits them in Detroit from time to time. They force money on him, stuff him with hot food and plead with him to stay home. King would take them up—except that after a few days at home, they begin demanding that he curb his drinking sprees. When they do, he goes back to the freight yards again. But now his life has him worried. In October he suffered a heart attack. He shows me a bottle of tiny white nitroglycerin tablets. “If in the morning you can’t wake me up, or if I’m acting funny, do me a favor, will you? Stick a couple of these under my tongue.”

Rail King strips down to his long johns and snuggles down into his sleeping bag. I tell him I can’t sleep because it’s too cold. He offers a solution. If I’m bold enough, I can break into one of the cars on an auto transport, start the motor of my car and ride to California with heating and radio, too. Gaining entry is simple; the keys are taped beneath the bumpers. But I’m to be careful not to cut my hand on the bumper metal when I reach underneath. I’m also to be forewarned that those cars are “an interstate shipment in transit”—Rail King has somewhere picked up that phrase—and that entering one of them by stealth is a federal offense. I decide not to ride out west in a Chevy. “Well, it’s up to you. I always say if you can’t do the time, don’t do the crime,” King advises. Then he asks me if I want to “get inebriated,” but I turn this offer down as well.

Freight yards, like graveyards, are not places where the timid should venture at night. Under the yellow yard lights, the cars become a foreboding, ominous gray. There is silence and then, as “switches” go by, a great roaring rumble that makes the earth quiver. When cars go past, they weave side-to-side on the tracks like drunks on a sidewalk, creaking and groaning, and sometimes spilling out their contents. The “power” comes by with a low, muffled hum that becomes a high- pitched whine after it uncouples its load. The stench of creosote, pungent by day, thickens at night until you think the very sky around you is a reservoir of pitch. Sirens howl and unintelligible barkings blast out of loudspeakers all around you. There’s the darkness and din of hell, and the lonely chill of empty warehouses in winter.

Suddenly our train lurches and starts rolling east. The car sways with every section of track we pass, and the axles make a screeching din that gets louder the faster we go. We near the hump, then take a track to the side of it, leaving it and the Liberty yards behind. The dozen tracks on each side of us turn into three, and there, somewhere in the countryside east of the city, we come to a stop. Everything goes quiet.

I can’t go back to the heater now, so I crawl between Leonard and Rail King and try to sleep, covering myself with the plastic sheet Leonard refused to use. I press close to Rail King, swathing myself with the edge of his sleeping bag, which keeps one side of me warm. Eventually I fall asleep. When I awake, the dark scenery outside has changed, and we’re rolling in the direction of the hump. Out the north door I see the rails split at its base, and this time, we are headed for the uncoupling terminal. Now there is no doubt that we’re going over the hump.

I holler out to Rail King and Leonard, but neither answers. King’s bottle rolls with a hollow sound down one side of the car; he must have finished it while I slept. The train slows, then creeps between two long blazing strings of lights, mounted about door level. The lights are so brilliant they illuminate the whole inside of our car. I see the figures of two men behind the lights; one of them is writing on a clipboard. Our car stops with a great bang, sending me careening unsteadily back to the west end of the car, where Leonard sleeps. We’ve been uncoupled. I ease my head out the south door. A few yards ahead of us there’s a gondola, drifting noiselessly downhill. It swoops down a bridge, and I hear a shrieking and see sparks fly from under its wheels. Apparently there’s a braking device built into the tracks. The gondola rolls on as if guided by an unseen hand. It turns and goes down a yard I can’t make out in the darkness. Then there’s a boom followed by a series of small roars that turn into a mere clacking, like the sound of dominoes falling.

Two or three cars are ahead of us in line; there’s still time to jump. I kneel over Rail King and tug at the top of his sleeping bag. He doesn’t blink. I lift up, raising him off the floor about a foot. I pull harder, raising his torso off the floor, and then I let him fall. He rises up, unsure of what hit him. “Little brother, what’s going down?”

“We’re right on top of the hump and they’re going to move us on off.” The King eases out of his bag and staggers in stocking feet to the north door. Then he unbuttons the fly on his long johns and urinates out the door. He crosses over to the south door and urinates again. “What are we going to do?” I demand.

“Shit, we’ll just ride the hump,” he mutters, stumbling off to his bag again. I’m sure he is unconscious by the time our silent descent begins.

I clutch hard at the doorway, looking out. Behind us there’s a tanker, just beginning its own roll as we come off the bridge and round the first bend. Our speed slows, but the tanker keeps coming, nearer to us now. Then it begins shrieking and throwing off sparks. Our creep around the turn is over now, and we gain speed on the straightaway slope, leaving the tanker almost out of sight. When I see the line of cars coming up in front of us, I pull my head back and close my eyes, awaiting impact. Slam, dat, dat, slam! We’ve hit. Somehow I held on, and it wasn’t as bad as I expected. I grab onto the doorway again and peek outside. The tanker is coming down behind us and—whoomp!—it hits, dislodging me from the door, but not knocking me down.

Rail King’s bottle has shattered against the east wall, but neither he nor Leonard has stirred. A quiet settles in, and I find myself thinking that there is no lure in the hobo’s life, or in the dimly lit half-lives of winos, either. Our folklore tells us that down-and-outers are really free, while the rest of us are chained to desks and accounting books. Hobos take life in its essence, stripped of care, inhibitions and the humdrum of the installment treadmill. But that’s the myth of the hobo, not what I see. Winos are not adventurous, they are backward-looking and usually inert, as well. Most of their time is spent in street-corner reveries. They only move under the pressure of bodily needs, and their chief need is a bottle of wine. Their only social outlet is conversation, and their conversation is neither creative nor oriented toward any end other than keeping memories alive. Most wino talk is set in stereotyped themes about the past: “I was” exaggerations, recollections of wives and families left behind, of victory binges gone by, and most of all, of the traumas that derailed them from productive life. The present for winos is the present bottle of wine, and the future is but a series of boasts about places that could be seen and money that could be made. But the day’s work is considered done when the morning’s bottle is in hand.

I feel the stinging cold again. Our D&RGW car won’t be going to California. We’ll have to pick a new train and another boxcar—and buy a new bottle—and it will be mid-morning before we get out of Houston, if we’re lucky. My patience is as thin as my cotton shirt, and I need a toothbrush, a shower and a shave. Worse, I’m down to three cigarettes. When I light one, it doesn’t smoke right. It’s been broken; the impact must have jarred me more than I thought. I’ve told the two tramps I’m out of money, and I don’t want to be reduced to the status of a cigarette bum.

I sit down on the doorway, dangling my legs out the car and looking north across the yards to Liberty Road, where buses will begin their routes in half an hour. If I pinch the broken ends of my cigarettes together, they might last that long. Once downtown, I can buy a whole carton, if I want. There’s no doubt now; the time for me to leave has come. I jump down off the car and begin walking across the yards, gravel crunching beneath my feet. No one calls out for me to wait. I wouldn’t turn back if they did.

- More About:

- Longreads

- Homelessness

- Houston