And in all this Yankee Nation

There’s no better place to go

For a quiet meditation

Than this ruined Alamo.

—“To the Alamo” by L. P. Baen

People expect it to be larger, they expect it to be visible for miles across an archetypal stretch of Texas prairie, perpetually silhouetted in a lavish sunset. What they find, of course, is a grim, gnarled building in the heart of downtown San Antonio, a building whose peculiar curved parapet has so long ago sunk into their consciousnesses that the actual sight of it would seem anticlimactic were it not for the fact that the Alamo, like certain great paintings, has an immediate force that can never be reproduced.

At the entrance they are met by high school girls in coonskin caps who say, “Hi! I’d like to welcome y’all to the Alamo” and hand them a leaflet. “Here is your passport to history.” The girls then point them in the other direction, across Alamo Plaza to a block of second-growth drugstores and pawnshops, and invite them to visit “Remember the Alamo,” a “dramatic reenactment” of the battle. The visitors, sensing private enterprise at work, mostly just tell the girls they’ll think it over while they tour the real thing, which after all is right in front of them and free. Then they take a picture of themselves in front of the famous Alamo facade, read a bronze inscription (“Be silent, friend. Here heroes died to blaze a trail for other men”), open the big, post-apocalyptic wooden doors, feel a wall of cool air from the dark air-conditioned chapel, and walk inside, where the first thing they encounter is a stern sign warning gentlemen to remove their hats, coonskin or otherwise.

Maybe they realize then that this is sacred, not just historical ground. The only sound in the chapel is the reverent shuffle of feet and the whispers of fathers misinforming their children. In a glass display case, David (never Davy) Crockett’s fork, one of its prongs missing, radiates such solemnity that it could be the shinbone of a saint. Positioned like stations of the cross along the thick, moist walls are sentimental and inexplicably eerie pictures of the Alamo defenders—Tapley Holland holding his hand over his heart and simpering angelically as he crosses Travis’ famous line; James Bonham bolting forth on his horse with a message from the besieged garrison; Robert Evans, in a greenish, predawn light, convulsing as he is shot in an attempt to blow up the powder magazine.

It’s those pictures I remember most vividly about my first visit to the Alamo, when I was seven years old and riding the crest of Alamomania generated by Walt Disney’s Davy Crockett. My brother and I were wearing T-shirts with fuzzy pictures of Fess Parker on the front and brown shorts which I remember as being subtly fringed to resemble buckskin. I had some standards—I knew it was a shade too goony to actually wear a coonskin cap—but I was still a fanatic. I was lucky enough to get my hands on a Davy Crockett at the Alamo set before some wretched toy consultant, no doubt thinking that a preadolescent consumership would never know the difference, began substituting plastic Indians for Mexicans.

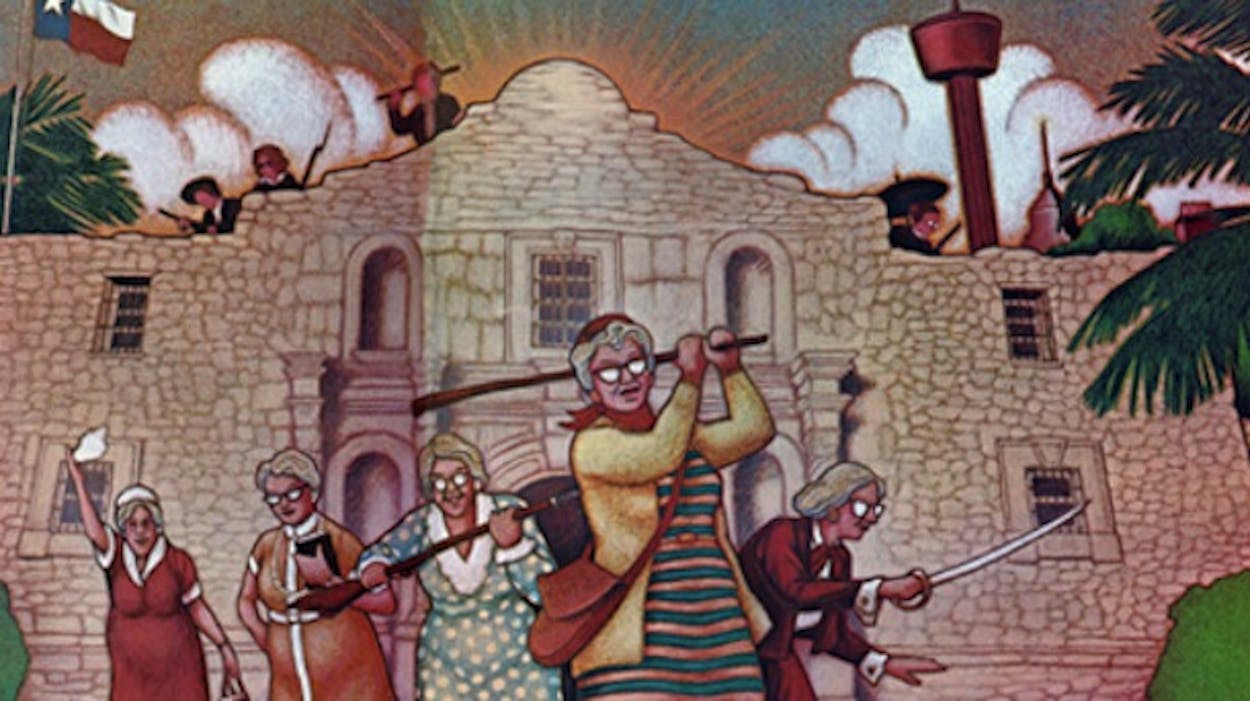

But they misjudged us. My generation was then transfixed, obsessed by a single image: in our heads Davy Crockett was forever up there on the Alamo ramparts swinging Old Betsy, toplling Mexican after Mexican off the scaling ladders, and never quite dying himself. That rifle was our common metronome, and there was only one song it kept time for: “Davy, Daaaavy Crockett . . . Last one to die at the Aal-amo!”

But that kind of rapture cannot last indefinitely. Now, of course, I realize that Davy Crockett was not the last one to die at the Alamo, or, if he was, it was because (as certain revisionist historians and general cynics have suggested) he lost his nerve at the last minute, tried to surrender, and was ignominiously executed. I realize, too, that Jim Bowie was in the Alamo fighting—in part, at least—to rebuild the fortune he had once made smuggling slaves with Jean Lafitte and selling fraudulent land claims, and that the men in the fort, as their once sure hopes for reinforcement faded, did not so much choose certain death as adapt themselves to the fact with a great deal of patriotic verbiage with which, to this day, anything connected with the Alamo is still inundated. I realize that, yes; but I walk through those doors, a full-grown cynical human male, and I know that if I had a hat on I would remove it.

Say, you talk of Balaklava

And the bloomin’ British Square,

Of Waterloo and Ballyhoo,

Why, that’s nothin’ but hot air;

Like the story of Thermopylae,

An’ yarns about the Greeks,

An’ Persians and Egyptians—

Not to speak of other freaks.

Why, sonny, down in Texas,

Not so very long ago,

They had a scrap with Greasers

At a place called Alamo.

—“The Alamo” by Horace Chaflin Southweck

“Remember the Alamo” is located on the site of the Alamo’s command post, which has long since disappeared but which is experiencing a form of reincarnation in RTA’s adobe-esque facade. The $1.50 ticket price for a half-hour slide show has drawn, on this day, only a handful of German-speaking tourists and a nostalgic journalist. The screening room, with long rows of benches, is nearly empty.

“Please sit in the second row,” a man in his early twenties says. It is such a weird request, with all that unoccupied space to choose from, that I feel compelled to comply. The usher has a brown mustache and a flashlight. His RTA uniform—brown pants, brown checkered shirt, brown bandana—looks like something you might wear to a very uptown square dance.

Soon the lights go out, the quad speakers blare out music appropriated from John Wayne’s $12-million epic The Alamo, and black-and-white drawings waft across the long slender screen, retelling once more that story we have all grown to love but have never quite gotten straight.

After 1821, Mexico opened its province of Texas to American settlers, promising each family vast quantities of virtually tax-free land in return for a token fee and at least a sniggering allegiance to Catholicism. The response was, of course, overwhelming, and the colonial government soon began to fear that the Anglos were pulling the carpet out from under them. They began to get bureaucratic, to levy taxes, and enforce the Mexican antislavery laws. Disillusioned and harassed, the Texas colonists in 1836 finally rose up in arms against the fatuous but not-to-be-messed-with Mexican dictator, the “Napoleon of the West,” General Antonio López de Santa Anna. The Texans won a few minor skirmishes and a major battle that gave them control of San Antonio de Bexar. Soon after, 183 of them found themselves besieged by Santa Anna himself in the Alamo, a failed, decaying mission half a mile from San Antonio named for the cottonwood trees that lined the acequias—ditches that flowed nearby.

The Texans endured a cannonade and false hopes for thirteen days. On March 6, 1836, a Mexican attack force of nearly 2000 men, wearing those tall Napoleonic hats that must have been difficult to balance on their heads, stormed the Alamo walls to the strains of the deguello, the old Moorish dirge that signified no quarter. The Texans were all killed, of course, but not before they inflicted heavy losses and bad PR on their assailants. The remainder of the Texas forces coalesced in rage, the Mexicans got theirs in about six weeks later at the battle of San Jacinto, and the Texas Republic was launched on its brief career.

It was a neat little package: heroic sacrifice, righteous indignation, just retribution, Independence. In an age of Byronic chivalry, there could not have been better candidates for sainthood than the men who died in the Alamo: besides a number of lawyers that would have been alarming even by contemporary standards, there were doctors, scurrilous charmers like Jim Bowie, inspired rednecks like Davy Crockett, engineers, farmers, poets, blacksmiths, adolescents, jockeys. The men in the Alamo constituted a microcosm of all that was genteel and legitimate in frontier life. They were too good to be true. They were good enough, in fact, to be more than true.

I must admit the slide show is a little more stirring than the above account. Dmitri Tiomkin’s music is still whirling in my ears when the usher comes up after the show to introduce himself. He’s not really the usher; he’s the assistant manager of “Remember the Alamo” and a descendant of John W. Smith, one of the last messengers from the Alamo, whose fortuitous timing helped him live to become three times mayor of San Antonio.

Joseph Judson is this descendant’s name. He’s a Son of the Republic of Texas, the male counterpart to the Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT), who run the Alamo and who, incidentally, are not too fond of his operation, which shrewdly plants its coonskinned barkers on the no-man’s-land in front of the chapel, thus leading tourists to believe that “Remember the Alamo” is officially sanctioned. Judson speaks about the Alamo like a son who’s just been cut in on the family business and has some great ideas for expansion. He praises R. J. Casell, his boss and the creator of RTA, for making the facade look “Alamoish.” He tells me about a new city plan to block off all traffic on Alamo Plaza and plant grass where the pavement is now, a plan opposed by the DRT because it would limit the Alamo’s frontal accessibility to pedestrians and divert tourists from the sales area, the Alamo’s lifeblood. “It’ll be tremendous,” he says.

“I definitely have feelings because of my family ties,” he muses in response to a question. “When I walk over there I look at those walls and I say, ‘Oh, wow, man, our freedom was made here.’ I mean if that had not happened this would all still be Mexico.”

When I was in the seventh grade and taking a compulsory Texas history course, the Daughters of the Republic of Texas sponsored an essay contest on “An Historical Figure In My State.” I chose William Barret Travis, the vain, 27-year-old commander at the Alamo whose psychotic fondness for gallant gestures appealed to me at the time. I won. I was invited to a DRT meeting where a red-headed cherubic little man sang (a capella!)

Beware! Beware! Of the green-eyed

Dragon with the thirteen tails!

He’ll feed—with greed—

On little boys’ puppy dogs

And GREAT BIG SNAILS!

I sat there befuddled, thinking that, since I was now a member of the literati, this must be Culture. When my name was called I brushed the petit four crumbs off my lapels and received an olympic-looking medal from a woman who seemed old enough to be my subject’s grandmother.

I mention this as background, because I am now once again in a room peopled with women who are directly (“not laterally”) descended from Texas heroes or, at the least, Texas residents during the time of the revolution and/or republic. The Alamo Committee, the group of the DRT that is responsible for running the Alamo, is meeting today in the Crockett room on the south wing of the Alamo’s superb DRT research library, which in turn is just south of the chapel or, as it is known in these circles, the shrine.

How the DRT ended up responsible for the Alamo is an interesting story. Several years after the battle the army rented the Alamo grounds from the Catholic church, restored the chapel, and used it as a supply house until 1876. Shortly afterward the state bought the property from the church, though the only other original mission building, the old barracks to the northwest of the chapel, was still in private hands. A dry goods store was built on the ruins of the barracks but was condemned in 1903, paving the way for a nasty little syndicate to zip in and buy up the property, with plans to build a hotel that would hunker down on the chapel itself. Enter Clara Driscoll, ranch heiress, art patron, and member of the twelve-year-old Daughters of the Republic of Texas. When the state balked at blocking the syndicate’s plans by buying the property outright, she put up a considerable amount of her not inconsiderable fortune to buy an option on it herself, forestalling an insufferable desecration and winning herself the title “Savior of the Alamo.”

The state eventually paid her back and, in a unique move, entrusted the Alamo itself to the DRT “to be maintained in good order and repair, without charge to the State.” Thus the daughters are all volunteers. “We’re so proud of the fact that thousands of free hours of love and care went into the making of this attraction,” says Mrs. Walter Gray Davis, chairwoman of the Alamo committee. “Thousands of hours were given to bring it to its present state of reverence and excellence.”

“Now I’d like you to meet some wonderful women,” she says, making a gracious sweep with her arm around the conference table. There are four other women present: Mrs. Bryce Hartman has four children and her husband has a PhD in psychology, Mrs. Alexander Fraser’s husband is a brilliant historian, Mrs. T. Kellis Dibrell’s husband is a lawyer, Mrs. Claude Aniol has a “wonderful husband in advertising.” Then Mrs. Davis looks at me in a way that makes me wonder if I’m expected to have a husband too. I will admit, here, to a little uneasiness: I have just remembered that in my prize-winning essay I had plagiarized a line or two from the DRT’s own Alamo brochure. That sin has been with me for a long time, and I feel a sudden urge to confess.

But Mrs. Davis is, as I have said, a gracious woman, and so are her fellow committeewomen. So I am soon once more at my ease, such as it is. Mrs. Davis’ well-coiffed hair is a handsome shade of steel blue in the light from the window behind her. She is a bright, genial woman, squarely into her prime, with a miniature gold Alamo pinned to her dress.

Another woman comes in: Mrs. A. Warren Holden, who is introduced as a descendant of Micajah Autry, the storekeeper-poet-violinist who died in the Alamo.

“You know, we really are proud of our heroes,” Mrs. Davis says, then asks me where I went to college. When I tell her the University of Texas she looks at me sadly.

“Well, I suppose you’ve been brainwashed then.”

I try to look puzzled

“What America needs is more heroes,” she goes on. “The Alamo stands for something that appeals to everyone—valiant devotion.”

Valiant devotion—though I have been brainwashed I find myself moved by that phrase. In each of the four chambers of my heart Fess Parker is swinging that rifle again. Yes, Mrs. Davis, I have plagiarized. Put the cuffs on me.

But instead she asks me what my views are on the battle of the Alamo. And, because I feel it is my job, I summon forth all my reserves of smart-ass sophistication and introduce the notion that the Texas Revolution might, after all, have had as much to do with land speculation and slave holding as with Truth, Justice, and the American Way.

Silence. I have just set down a rattlesnake on the conference table.

Mrs. Davis shakes her head and quotes Ronald Reagan: “You can’t have freedom without prosperity and prophet.”

“Maybe these men came here seeking freedom for themselves,” says Mrs. Dibrell in a fine, quavering, indignant voice, “but they did not have to stay. They did not run away. They stayed and gave their lives.” She abruptly leaves the room and returns with a copy of a speech given at the Alamo by a general several months earlier: “Here 186 men stood, fought, and died—that others, as yet unborn, might live, free of tyranny.”

The women are slowly recovering. But it has been a shock to all of us that one of those “as yet unborn” people should speak such heresy.

“They died for something they believed in and that is a fact!” Mrs. Davis says.

“They decided to stay just as people today do,” Mrs. Fraser says.

“But would people stand that way today?” Mrs. Davis counters? She shakes her head. “No, I don’t think they would.”

Thou Alamo! Thy tale I read

In youth, nor deeming I should tread

Thy hallowed floor of sacred earth

Where Texas Freedom had its birth.

—“Thou Alamo” by Samuel L. Watson

The “sacred earth” has long been buried under a cool cement floor, a floor that is trod each year by a million and a half tourists who bring in so much sweat that the Alamo is now covered with a chemical preservative to protect it from mildew.

Not only the floor has changed. The Alamo chapel bears about as much resemblance to itself during the siege as it does to the gazebo across the plaza. The curved parapet that pulls the architectural lines of the chapel together into a kind of topknot, the one feature above all else that gives the Alamo its identity, was not even in existence until some fourteen years after the battle, when the army made gestures toward preserving the old building. During the siege the chapel, which originally supported two huge bell towers, was a crumbling mass of stone that ended where the upper windows of the present Alamo begin, so that the effect of looking at period pictures of the chapel is like seeing an old friend with a new crew cut.

Equally disconcerting is the fact that the old mission walls—which once put the chapel into dwarfed perspective and would have enclosed what is now known as Alamo Plaza and the area from Sommers drugstore on the north to a five-and-ten having a going-out-of-business sale on the south—are gone entirely, except for the barracks building that Clara Driscoll salvaged. Santa Anna, hoping to flatten the fort that had held up his advance for a precious two weeks, had most of the walls torn down after the battle. Private enterprise and improvident city planning took care of what was left. So today the chapel—face-lifted, air-conditioned, detoxified, roofed, landscaped—is virtually all that remains of the Alamo.

These may be serious considerations for historians, but for the average citizen, primed for the Bicentennial, the Alamo is just fine the way it is. It has grown beyond such nit-picking; it has eclipsed its own history. It seems that anyone with the right connections and a flair for rhapsodic phrase making can have his words chiseled into marble or cast in bronze and displayed somewhere on the Alamo grounds, and the weight of all that accumulated rhetoric has helped create an Alamo that is as real in its way to us as its earlier version was to the men who died there.

This one building, after all, is the Alamo that the public psyche has conjured up, the one that shines forth from the centers of road maps and lends its name and likenesses of its facade to hundreds of businesses. There is probably not a city in Texas, in America, without a building or a house echoing the curved top of the Alamo. Though Six Flags Over Texas has replaced it as the state’s number one tourist attraction, though the son of a Saudi Arabian sheik has assumed it could be for sale, though the Rolling Stones have stood in front of it and made faces, the Alamo has endured with a kind of twisted grace; everything in Texas is, somehow, peripheral to it.

Today, at the spot where Jim Bowie, dying of typhoid-pneumonia, was bayoneted on his cot, a woman in a green vest watches as a man, identically attired, walks around the gazebo, preaching in rage to a bum who has fallen asleep on a concrete bench made to resemble the hollow of a petrified tree. The “Remember the Alamo” girls have traded in their coonskin caps for plastic cowboy hats. I accept my passport to history from one of them and slip through the doors of the chapel.

The dank, musty smell I remember from my first visit, the smell I’ll always associate with history, is gone, sucked out through the air-conditioning ducts. But the place is still forlorn and forbidding. In the display cases are old, old letters: Asa Walker apologizing to a friend for stealing his rifle on the way to Texas—“your gun they would have had anyhow and I might as well have it as anyone else”; Micajah Autry to his wife—“Farewell my dear Martha till I write you from Louisville or Cincinnati”; and on the walls those bizarre, outrageous pictures, those men with their death-wish smiles, their fluttering hearts…

The souvenir building is a little easier to handle. Here is Americana at its most accessible: T-shirts, bibs, plastic powder horns, Kachina dolls, literature, coonskin caps, his and hers “chopper hoppers” for the storage of false teeth, $30 bloodcurdling replicas of Bowie knives, longhorns, jewelry. This is where the Daughters make the money required to run the Alamo. The souvenir building is tactically placed directly in front of the only exit leading from the Alamo chapel. It’s a marvelous system. On leaving the high-powered sanctity of the shrine one’s first impulse is to do something base and commemorative, like buying a little upholstered dog that will sit on your dashboard, wag its heard, and constantly remind you “You’ve been there, boy, you’ve been to the Alamo.”

Inside the long barracks is a good museum equipped with audiovisual aids and neat little dioramas that would put my old Davy Crockett set to shame. The museum is run by C. J. Long, who is also the curator of the Alamo and a veteran of 24 years with San Antonio’s Witte Memorial Museum. Long is one of 36 people, many of them professional librarians and historians, who are hired by the DRT to maintain the site.

“You know,” he says, “the Daughters deserve all the credit in the world.” I am talking to him in the bright, midday sun of the courtyard, and there is so much glare on him that I can make out little more than a red face, sunglasses, and a blue blazer.

“People don’t give the Daughters actual credit. They get bad publicity from every angle. But they all have a deep interest.” He gestures back toward the souvenir building. “This is the only historic monument in the world that pays its own way.”

“People come here from all over the world,” he says. “South Africans, New Zealanders. Some of these tourists drive 2000 miles just to see it. It used to be that people had no real idea what went on here, but we’re doing a better job now, telling a better story. People have a better idea of what to look for.”

That seems to be true, thanks to Long’s easily comprehensible museum exhibits. But Alamo staffers can tell you some whoppers: like the woman who called down from Connecticut, wanting to know exactly what went on in the minds of all those Englishmen in the Alamo before they died; or the man overheard explaining to his wife that it was here that Teddy Roosevelt recruited his Rough Riders for the assault on San Juan Hill.

“All Texans… are now insisting that the memory of the Heroes of the Alamo shall be honored with some tribute that measures up in its character to the grandeur of their martyrdom.”

—from the Alamo Magazine, April 1915

A rather large order. What the proponents of this tribute had in mind was nothing less than the “tallest building in the world”—“802 feet of marble, granite and steel,” with “no less than 300 rooms, each 14’ by 20’… on the top will be a wireless station for government service and here, too, will be a wonderful revolving searchlight of enormous candle power.”

The tower was never built, much to the chagrin of any Dadaists who might have existed in San Antonio at the time. But the authors of the project have left behind a sketch for a cheated posterity. The tower is a soaring grab bag of Byzantine vaults, obelisks, gargoyles, spires, and Mount Rushmore-sized statues of the Boys. At the bottom of the sketch, looking like a pea snuggled up against a telephone pole, is the Alamo itself.

The Alamo was not to have a bona fide monument until 1939, three years after the centennial of the battle. What it got, of course, is the Alamo cenotaph—the word means “empty tomb”—a structure of white marble designed and executed by “famed Italian sculptor” Pompeo Coppini. The cenotaph was greeted with customary irascibility by J. Frank Dobie, who pointed out that it looked like “a grain elevator, or one of those swimming pool slides which you climb straight up on one side and then on the other side scoot down into the water.”

But nobody has ever torn down a building just because J. Frank Dobie didn’t like it, and there it sits today in the center of Alamo Plaza, an empty tomb which, from the outside, does indeed look like it has a lot of unoccupied crypt space. From its front the “Spirit of Sacrifice” rises in bas-relief, while on its sides excessively handsome depictions of Travis, Crockett, Bowie, Bonham, and lesser heroes gaze wistfully toward, we can only guess, the land which they gave their “marytyrs’ blood” for and which has fallen to you and me to inhabit.

There are other monuments all over the beautifully kept Alamo grounds. Every surface with four sides is inscribed, as by some quadruped Kilroy, with the names of Crockett, Bowie, Travis, and (well, he’s nearly famous) Bonham. But my favorite is the stone presented to the Alamo in 1914 by the Japanese people, in whose history a similar battle occurred. The poem inscribed in Japanese on the monument was once rendered into a lovely and bizarre translation by a Japanese exchange student:

here the one hundred and eighty-two

laid their corpses in a heap,

and not a soul surrendered.

The people of the twenty-four districts

get inspiration thereby and learn for the first time

the superiority of the unanimous

co-operation of men to

geographical advantage . . .

“Let me tell you a story,” Mrs. Holden says. She has broad, riveting features that she manages to keep in profile even as she turns to fix me with a look that implies my imminent salvation.

Fifty years ago—longer, she tells me gently, than I have been alive—Mrs. Holden brought her grandmother, the daughter of Micajah Autry, to San Antonio so that she could see, for the first time, the site of her father’s death. She was a small, frail woman, stone deaf.

“When my grandmother came into the Alamo—it was late in the day and it was almost closed—this tiny little woman folded her little hands, walked through the door, and said, ‘Father! O my Father! Peace be to your ashes and peace to those who killed you!’

“Peace be to your ashes and peace to those who killed you,” Mrs. Holden repeats quietly. “And do you know, they wouldn’t take one cent for her room at the Saint Anthony? Even the cab driver told me, ‘Lady, you can pay for yourself but you can’t pay for the little old girl.’”

There is silence around the conference table. The rest of the women are discrettly bowing their heads and wearing reflective half-smiles, the kind that are rooted in the glories of the past.

“Now that,” says Mrs. Holden, turning full-face for the first time, “is a human sotry!”

In the southern part of Texas, in the town of San Antone,

Like a statue on his pinto rides a cowboy all alone.

And he sees the cattle grazin’ where a century before

Santa Anna’s guns were blazin’ and the cannon used to roar.

And his eyes turn sorta misty, and his heart begins to glow,

And he takes his hat off slowly to the men of Alamo. . . .

—“The Ballad of the Alamo,” sung by Marty Robbins

Late at night I drive from my hotel and park in front of the Alamo. The spotlights at its base have cast the Chapel in an ethereal bright beige. Each stone is distinct, and the building itself is harsh and insisten against the night sky. It looks like a wizened knot in the heart of an ancient tree, liek something alien wrenched up from the center of the earth by a geologic upheaval.

It’s haunted, of course. In 1893, when it was a police station, several officers complained of hearing, on rainy nights, “the measured tread of heavily armed and booted men on guard.” They brought in Miss Mary Mareschal, a nineteen-year-old medium, who promptly fell into a trance and announced, “The forms say they are the spiritual defenders of the Alamo. They say there is buried in the walls of this building $50,000 in $20 gold pieces.” She was about to point out exactly where when the spell was abruptly broken.

The ground beneath the Alamo is crisscrossed with aquifer systems that form occasional tunnels through which the men of the Alamo are said to have escaped or, in another version, through which their spirits forever ramble, searching for a way out.

But the Alamo is haunted in less obvious ways. It has stood in that same spot for 200 years while the city of San Antonio and its inhabitants and its visitors have swirled incessantly around it. Every day friends say, I’ll meet you at the Alamo.” In its presence lovers renew and renounce vows, junior high school history teachers swoon, artists put away their half-completed sad clowns and bluebonnet fields and try to paint it, jaded businessmen and cab drivers try to ignore it, and homesick Arabs, maybe thinking of the Alhambra, try to buy it.

“Blood of heroes hath stained me.” True enough. Though the blood has long since soaked below the pavement and the Alamo is stained now with silicone, true enough. There is something powerful and unavoidable lingering about the chapel’s flat, almost one-dimensional facade. I stand here, at night, holding in my hands the keys to a Toyota instead of the reins of a pinto, and, well, my eyes turn sorta misty.