In the tiny West Texas town of Iraan, the drumming begins two hours before game time. A dozen or so fans of the Iraan High Braves, already at the football stadium, pound on tom-toms: one loud beat followed by three lighter ones, over and over and over. The sound of the drumming carries all the way across town and echoes off the nearby hills and mesas, and soon more fans arrive, many of them, adults and students alike, wearing war paint on their faces. Some carry homemade spears, made of PVC pipes with rubber tips, which they bang on the metal bleachers, keeping time with the tom-toms. Others shout a war chant while they hold up their arms and make tomahawk-chop gestures.

By kickoff, close to 800 of Iraan’s 1,200 citizens are packed into the stadium. The ninety-member Big Red marching band launches into the school fight song, and the six varsity cheerleaders turn backflips. When the Braves run onto the field, the roar from the crowd is almost deafening—“like something you’d expect at a college game,” says Clara Greer, the editor and publisher of the weekly Iraan News. “In Iraan, we have no roller-skating rinks or bowling alleys or movie theaters. For our entertainment, we’ve got the Braves. Out here, Friday night football really is the one thing we live for.”

In the fall of 2007, the Braves were led by four good-looking kids. One, the son of the town’s bank president, was the steady, sure-handed quarterback. Another, the son of a coach, was a deceptively swift running back. The third, the son of another coach, was the team’s best lineman, and the fourth, a blond-haired boy who looked as if he had walked straight out of an Abercrombie & Fitch advertisement, was such a magnificent defensive back that Texas sportswriters would later name him to the class 1A all-state team.

Because of their gridiron exploits, the Braves advanced to the state playoffs, and there was talk around town that the team had a shot at the state championship, which it had last won in 1996. The four boys were treated, in the words of one resident, like “the town’s celebrities.” Whenever they walked into the Old House Cafe, Iraan’s gathering spot, older men nodded at them appreciatively. Children asked for their autographs. Teenage girls, sitting at the back tables, raised their eyebrows whenever they walked by and shyly said hi.

But in early December, the Braves faltered in the regional playoff game against one of their top rivals, the Nazareth Swifts. In the fourth quarter, the quarterback threw a rare interception, the all-stater made a bad punt, and Nazareth scored 18 unanswered points in the final nine minutes of the game to win 24-17. Many Iraan fans were teary-eyed. But they kept reassuring one another that everything was not lost. After all, they said, the team’s four stars would be back the next year to lead them into the playoffs once again.

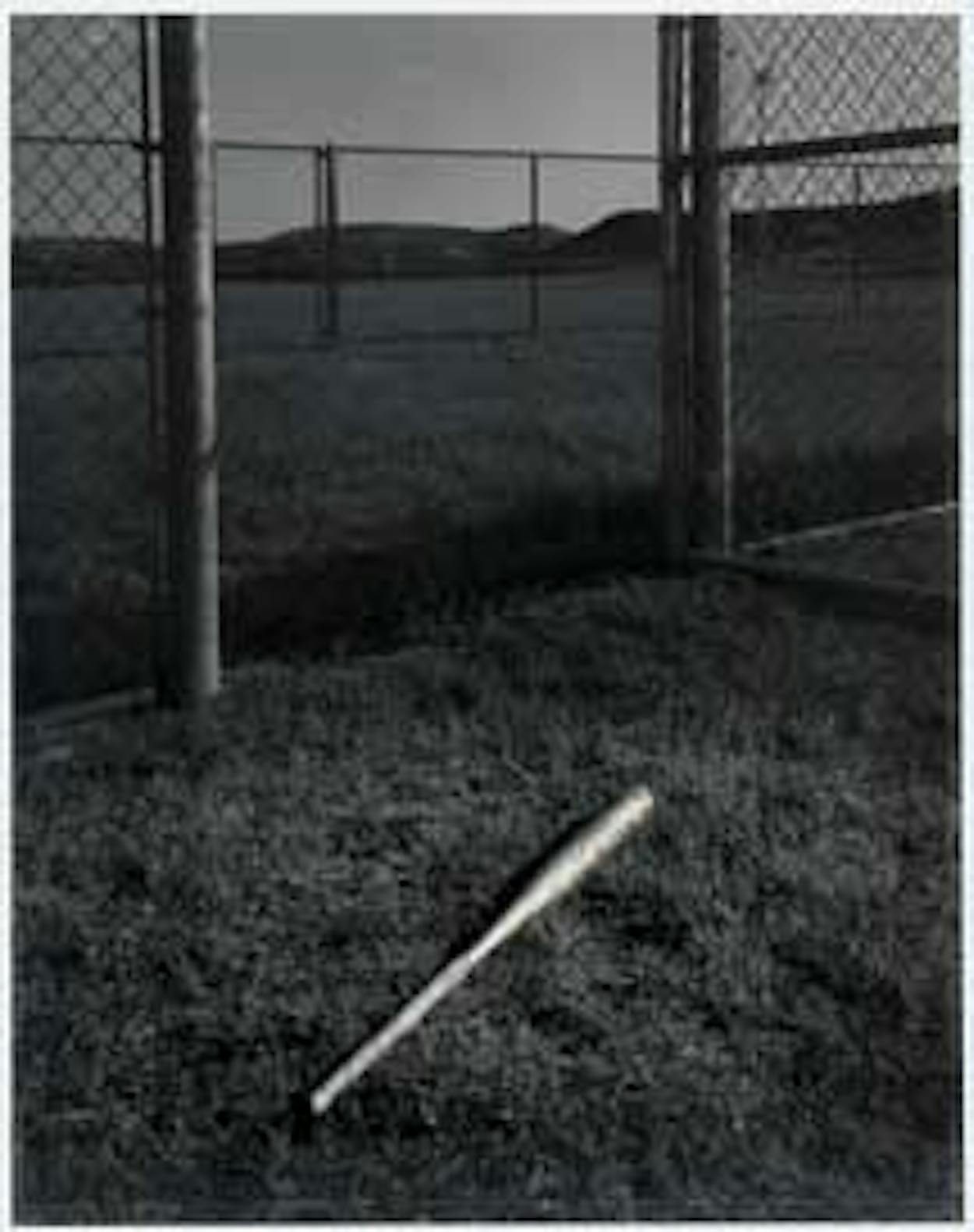

Six days later—on the first Friday night the football team had had free since the beginning of the season—the four boys met at the Old House to eat. Afterward, they climbed into a pickup and made the loop around town, ending up at the high school baseball stadium. Deer often frequented the outfield, coming down from the nearby hills and leaping over the fence to nibble on the grass, and this night was no different. The boys spotted a number of them, their white tails flicking. One, a mature doe, was grazing near a button buck, probably no more than six months old, his tiny antlers just beginning to show.

The boys jumped out of the truck and gave chase. Before long, they had cornered the two deer in a bull pen. They shut the gate, got back in the pickup, drove to their homes, and retrieved a blue aluminum baseball bat and a wooden-handled shovel. They also picked up a golf club and a homemade spear not unlike the ones Iraan High fans brought to football games.

Then, they returned to the bull pen. The two deer were panicking, defecating as they ran from one end of the enclosure to the other. But they didn’t run for long. The boys raised their makeshift weapons and began swinging. One of them slammed the baseball bat into the doe’s skull. Another walloped the button buck with the shovel.

The hits kept coming, one after another. Within minutes, the four football stars had bashed in the deer’s heads. They jumped back in the pickup and drove away, leaving the deer twitching in the grass.

A school maintenance worker discovered the dead animals on Sunday morning. School officials notified a Pecos County sheriff’s deputy, who called the local game warden based in Iraan, Chris Amthor. He drove out to the bull pen, took one look at the gaping head wounds, and promptly called his boss, Captain Scott Davis, whose office is in Midland, 85 miles to the north.

The burly Davis, who has been a game warden for 23 years, is a conservative, churchgoing man: On the wall behind his desk is an illustration of George W. Bush praying with Abraham Lincoln and George Washington. “When Chris told me that two deer had been beaten to death, I wasn’t real sure what to think,” he told me. “I’d never even heard of such a thing. I thought, ‘What kind of person would want to do something like that?’”

Rumors about the killings were already flying through town—the culprits were either a couple of drunk oil field workers or some illegal immigrants. Someone said the deaths had to be the work of a satanic cult. But then Amthor heard that the sheriff’s department had received an anonymous tip from an Iraan woman who had overheard a story being spread around by some high school kids: The deer killers were Iraan High’s four football stars.

On December 14, five days after the deer had been found, Davis and Amthor visited the school and told Principal Benny Hernandez that they wanted to talk to the quarterback, Call Cade, and the running back, Zac Owen, both of whom were seventeen. (They didn’t initially approach the lineman and the all-stater because they were minors, ages fifteen and sixteen, and their parents were required to be present. Authorities have never officially revealed the minors’ names. I also agreed not to name them at the request of school officials and one of the parents.) Although the clean-cut boys looked like the last people who would commit such an act, Davis and Amthor gave them stern looks and said they wanted to know exactly what had happened.

There was silence. Then, to the wardens’ astonishment, Call and Zac immediately confessed. Their faces ashen, the boys said they couldn’t explain their actions, only that the night had gotten out of hand. Later, when the wardens met the lineman and the defensive back with their parents, they too confessed. The way one of them told it, once they had penned the deer and headed off to get weapons, “no one thought to say, ‘Whoa.’” In a written statement he later gave the wardens, Call simply wrote, “Our reasons for doing [the killings] is none other than being stupid and immature.”

Davis and Amthor decided to issue each teenager two misdemeanor citations: hunting white-tailed deer in closed season (“closed season,” in this case, referring to hunting at night, which is illegal) and hunting white-tailed deer with illegal means and methods (in Texas, deer hunters may use only legal firearms or archery equipment). A justice of the peace ordered each boy to pay around $800 in fees and fines, plus court costs, and she also placed them on a five-month probationary period, meaning that if they stayed clear of trouble during this time, the case against them would be dismissed. Meanwhile, school officials decreed that the boys spend the remainder of the fall semester and the upcoming spring semester in a disciplinary alternative education program; they would take classes by themselves in a small, off-campus house owned by the district.

Perhaps because she didn’t want to embarrass the football stars or their parents, Clara Greer didn’t run a single article in the Iraan News about the deer killings. The San Angelo Standard-Times, a daily newspaper based 115 miles east of Iraan, published a story about the incident, but it was brief and rather bland, ending with a simple quote from school superintendent Kevin Allen, who said, “We’re very surprised that these kids would do something like this. These are good kids.”

And that seemed to be that: one of those curious cases of some bored small-town teenagers going a little crazy on a Friday night. No one could have possibly predicted what was about to happen next.

What happened was that the Associated Press, relying on the Standard-Times’ article, produced a short story of its own about the killings, its editors no doubt figuring a few Texas newspapers might use it as a back-page filler item. In another era, no doubt, that’s where the Iraan deer killings would have stayed—on the back pages. But today, in the Internet age, any bit of news, even news that takes place in an isolated West Texas town, races around the world in mere minutes, and it wasn’t long before the AP story was bouncing from one Web site to another. It eventually landed on the desks of executives at People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, who promptly issued an action alert from their headquarters, in Norfolk, Virginia, declaring that the boys were in fact not “good kids” but genuine threats to society. One PETA animal-cruelty caseworker went so far as to suggest that the four were on their way to becoming the next Jeffrey Dahmers. “All of our serious serial killers and school shooters were known to abuse animals before they committed crimes against humans,” she proclaimed in an interview, citing FBI statistics. In another interview, the director of PETA’s Domestic Animal and Wildlife Rescue and Information Department, Daphna Nachminovitch, said the boys needed to be sent to prison. “The terror and agony that these deer experienced,” she said, “demands that the alleged perpetrators be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law.”

If PETA officials were hoping to create a “national media firestorm,” as one West Texas reporter later wrote, they certainly succeeded. Almost immediately, Davis was inundated with several thousand letters and e-mails from animal lovers in nearly every state in the country and from as far away as Australia, most of them demanding that he file animal cruelty charges against the killers and get them off the streets. Some argued that the boys should spend at least 23 months in prison—the very sentence that former Atlanta Falcons quarterback Michael Vick had received that same month for financing a dogfighting ring and torturing and killing pit bulls. On blog threads and message boards, others made it clear that “the Iraan 4,” as one writer dubbed them, deserved much more than time in the penitentiary. One woman suggested they be sent to Alaska—“or better to far off Siberia.” Another proposed they be beaten exactly how the deer had been, adding, “May I volunteer as the first to swing the bat?”

What particularly outraged people was the premeditated nature of the boys’ outburst. “They must have excitedly locked the gate, and made up a plan as to how to herd the two terrified animals closer and closer to the kill area,” remarked one blogger. “This to them was the height of hilarity and glee.” “Mark my words,” wrote another, “some day a young woman will be beaten like this mother deer and her baby, and that same young man who wielded the baseball bat right before Christmas in 2007 will stand over her and laugh.”

The anger was not just directed at the football players. Critics attacked Iraan itself as a backward, football-crazed town that cared more about the fortunes of the Braves than the pursuit of justice. According to online speculation, the only reason the teenagers hadn’t been expelled from school was that officials wanted them back in uniform for the following season. “This is about adult corruption and failure to lead and enabling killers to run free and prosper,” read one typical rant. “The deer did nothing except suffer mightily and die in pain and confusion. The guilty are doing nothing but laughing and having fun.”

“It’s as if people think we’ve created four monsters down here,” an exasperated superintendent Allen told me when I first visited Iraan, in February. “But I am absolutely telling you the truth when I say that these boys were good kids. They made A’s and B’s in school. And until this thing happened in the bull pen, they had never given us one bit of trouble, not one. They probably hadn’t even been tardy to class.”

So why did four teenagers who could have been cast members on Friday Night Lights suddenly transform themselves, on a mild December night, into depraved characters straight out of Lord of the Flies? Was it possible that PETA was right—that the boys had revealed themselves to be genuinely dangerous criminals who would one day kill again? Was it possible that the boys, for some unfathomable reason, had lost their grip on reality?

Residents of Iraan (pronounced “Ira-ann”) like to say they live “two miles from nowhere,” and it’s hard to argue with them. The town sits at the edge of the Trans-Pecos region, one of the most remote places in the state. It is usually impossible to get a cell phone signal unless you stand in the high school parking lot and hold your phone toward the sky. If you want to buy nice clothes or see a movie, you have to drive to Midland, Odessa, or San Angelo.

Iraan is named, predictably enough, for Ira and Ann Yates, the owners of a ranch where a giant oil field was discovered in 1926. During those boom days, 1,600 people lived there, but because Iraan was almost completely surrounded by the Yates ranch, it was never able to get much bigger. Today it remains just 0.6 square miles in size. “It’s the kind of town where everyone knows everyone else,” said Allen, a soft-spoken 51-year-old Houston native who moved to West Texas seventeen years ago so that he could raise his children in a small community. “Everyone in Iraan even knows what kind of car or truck everyone else drives. It’s not exactly the kind of place where you can keep many secrets.”

Most of Iraan’s small businesses are scattered along U.S. 190, which cuts through the center of town. Besides the Old House, there are a couple of Mexican restaurants, a couple of convenience stores, a hardware shop, a motel, a hospital, an RV park, and a handful of oil-field supply companies. On the north side of town is the Alley Oop museum and park, which contains some dinosaur sculptures. (The park was named in honor of the nationally syndicated Alley Oop comic strip, created by a local newspaperman in the thirties.) On the south side of town is Iraan High.

Every morning, Principal Hernandez walks up and down the school’s lone, long hallway, checking on his 132 students. He cheerfully slaps them on the back while giving them a once-over, making sure they are adhering to the school’s strict dress code. (Boys must keep their hair off their ears; girls’ skirts must come no higher than just above the knees.) “Because we’re so small, we’re able to keep tabs on all our kids,” he said. “Seriously, before the morning bell rings, I already know who’s absent.”

Hernandez makes a point of pushing his students to participate in as many after-school activities as they can handle. At University Interscholastic League competitions, the school often shows up with a full contingent of debate teams, science and computer teams, musicians, and a one-act-play troupe. And then there’s football. Of the 65 boys at Iraan High, 41 played on the team last year. “That’s always the way it’s been here,” said head coach John Fellows, who has coached the sport in West Texas since 1998 and who moved to Iraan in 2005. “If you’re born a boy in Iraan, there’s a good chance you’re going to be on the football field, no matter how big you are.”

By all accounts, the four football stars were prototypical West Texas teenagers—none more so than Call, whose father is the president of the one-story TransPecos Bank, just a couple of blocks from the high school. Named for Woodrow Call, the hero of Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove, he learned to hunt and to cowboy at the family’s ranch outside town; he also grew to be an excellent golfer, playing weekends on Iraan’s dusty nine-hole public course. Zac, for his part, had a reputation around school for being the class jokester, “the kid who’s always laughing, always putting a smile on everybody’s face,” according to Hernandez. The principal described the lineman, who was also president of the student body in 2007, as “one of those kinds of kids everyone puts on a pedestal.” As for the all-state player, he was “about as easygoing and nonchalant as you can imagine, someone who never has a bad word to say about anyone.”

Zac was the only one of the four who would speak to me, which he did in the presence of his father—the Braves’ defensive coordinator—and superintendent Allen. Wearing a blue T-shirt and a chain with a little cross around his neck, he sat at a conference table in Allen’s office and nervously ran a hand through his curly black hair (which was cut well above his ears). I started off the conversation by asking what teenagers in Iraan do for fun. He shrugged. “We go to the Old House to eat, then ride around, talk to our friends, things like that. You know, it’s a small town. There’s nothing really to do here except hang out. You can get bored pretty easily.”

Zac admitted that, to entertain themselves, he and his fellow football stars, along with a few other friends from the team, had chased deer in the baseball field on another night earlier that fall. “We were doing the loop, and when we drove by the baseball field, we saw the deer. We chased them around the outfield until they jumped back over the fence.” Then he said something revealing. “It didn’t seem that big of a deal—something to do, I guess. They were just deer.”

There is no question that the town’s residents have a different attitude toward deer than city dwellers do. In Iraan, deer are everywhere. Residents constantly complain about their slipping into town at night and devouring their flowers and gardens. Farmers and ranchers complain about their going after crops. “I know people are going to take this wrong, but out here, a deer isn’t Bambi,” the mother of one of the players told me. “Our deer are a nuisance. And they can be very dangerous. Every couple of weeks, you hear a story of someone wrecking their car because they collided with a deer. If you don’t believe me, all you have to do is drive down a highway around here and look at all the dead deer on the side of the road.”

What’s more, just about every male in Iraan has gone deer hunting. “When my son was in the fourth grade,” said the mother, “his dad took him hunting, and he shot his first deer, a small one. We had a taxidermist mount the deer’s head on a plaque, and underneath the plaque we had a humorous inscription typed up: ‘Deer Tremble in His Presence.’” She sighed. “Well, it was humorous at the time.”

When I asked how she and her husband had reacted when they’d learned that their son was one of the deer killers—according to the game warden’s report, he had wielded the spear—she replied, “Not very well, believe you me. I took my son out of class, took him home, and kept saying, ‘What were you thinking? What were you thinking?’ And all he could say was, ‘Mom, we weren’t thinking.’ And I believed him. Listen, I know my son. He’s not violent in any way. None of those boys are. They did a stupid teenage thing, and they’ve learned their lesson.”

The mother added that the boys have learned another lesson about those who live outside small-town Texas. “I had to sit down with my son and explain to him that people in places like New York City don’t understand us. That’s what this is all about, you know. The ones who are most upset are people who only see brown-eyed deer in movies. If the boys had killed some rats, no one would have said a word.”

In the aftermath of the boys’ crime, numerous West Texans would make similar points. “You city folks should not even comment because you don’t know anything about growing up in a small town,” one Iraan resident posted on the Odessa American’s Web site. “Go Braves.” Another chimed in, “You animal huggers need some common sense. Deer are a pest. They are not a domesticated animal like a dog, so saying that these boys should be treated the same as Michael Vick is a little outlandish.” “All of you city people think that deer are such precious little animals that eat only a little bit,” a farmer wrote to the San Angelo Standard-Times. “Well, try losing $80,000 in income during the 2006 fiscal year you morons.” What also dumbfounded West Texans was that the animal rights activists seemed to care more about the dead deer than about violent crime against human beings. “Why aren’t you people who are so concerned about what those 2 deer suffered commenting about the atrocity of a parent beating a child to death?” wrote one woman, referring to a recent murder case in the Midland-Odessa area. “They were deer, and these are just kids,” someone else summarized. “Do we really need to read anymore into this?”

At one point, Call’s father, Jim Cade, became so enraged by all the Internet chatter describing his son as a future serial killer (as well as online rumors suggesting that he had bribed law enforcement officials to keep his boy out of jail) that he hired a Washington, D.C., law firm that specializes in Internet law to try to find out the identities of the anonymous bloggers and perhaps sue them for defamation. Jim himself was once a West Texas football star—he played cornerback for the Sonora Broncos during their 1970 state championship season—and he is clearly a huge fan of the Iraan High team: One of his business ads, which runs in the Iraan News, reads, “TransPecos Banks: Proud to be Home of the Braves.” During one of my visits to Iraan, I dropped by his office. Wiry and muscular, built like a bull rider, he was wearing a crisp shirt with pearl-snap buttons, blue jeans, and tie-up ropers. Although he was not at all happy to see me—he let me know immediately that he was not going to talk about his son (whose photo in full football uniform was prominently displayed on a shelf) or the deer beatings—he gave me a firm handshake, pointed toward a chair, and asked what kind of story I planned to write. When I said that I was going to mention how the killings had set off a national furor, he just shook his head, disgusted.

“I grew up on black and white television,” he said. “Gossip was conducted over the back fence. Now people can say anything they want, put it on the Internet, and it goes around the world, no matter how big of a lie it is. It’s just not right, what people have done to us.”

Actually, not all the criticism came from outside West Texas. There were a few people in Iraan who were horrified by the boys’ violent outburst. “Listen, I’ve been around the block,” said one longtime resident, Gwendolyn Parker Scallorn, a feisty, plainspoken woman whose late husband was the superintendent of the natural gas plant in town. “I know boys will be boys. But this made me sick to my stomach. It felt like murder. Some people felt that if these boys didn’t get into counseling and find out why they did such a thing, then we would be reading about them again someday in the newspaper—and it wouldn’t be pretty.”

A few veteran deer hunters in the area were especially disturbed that the boys had wanted to club the animals to death—and had then left them on the ground to rot. Although West Texas hunters are not exactly the kind of men one would describe as sensitive to a deer’s emotional state—a common boast is to have “dropped the hammer” on a beautiful buck—they do take great pride in what they call a “clean kill,” bringing down a deer with one perfectly placed shot just behind the shoulder blades. A hunter’s code also requires retrieving the carcass, for processing the venison and later consuming it. But as one self-described outdoorsman commented on a Midland television station’s Web site, when the four boys went out to kill deer, they obviously “weren’t looking for a trophy, they got a thrill from torturing animals—which leads me and plenty of other reasonable-minded people to believe that they have sadistic and abusive elements to their personalities.”

The respected outdoor-sports columnist for the Austin American-Statesman, Mike Leggett, who does his share of hunting in West Texas, was so sickened by what the boys had done that he wrote, “Instead of letting these kids back on the football field next fall, let them spend Fridays patrolling highways around Iraan picking up dead animal carcasses. If they wade through enough skunks, coons, snakes and flattened deer while their buddies are wading through cheerleaders and pep squads, maybe they’ll take something from this other than a fine and an adjudicated sentence. . . . There can be no lesson learned and no lesson taught unless they pay a real price for what they’ve done.”

But in mid-March a committee of high school teachers and administrators, appointed by Hernandez, decided that the lesson had indeed been learned. The boys had been model students for 46 days, they concluded, and there was no reason for them to complete the rest of the semester in detention. A Midland psychologist who had been hired by the district to evaluate them noted that they had shown no “anger issues” or emotional disorders that might suggest they would commit further acts of violence. Davis was also satisfied that the boys had been punished enough. “Listen, I’ve been around a lot of hardened, calloused kids who I knew were going to cause trouble for years to come,” he told me. “These boys weren’t like that. They told us the truth about what they had done. And they seemed genuinely remorseful. They also didn’t have any prior criminal record, which to me was significant. In the end, I didn’t feel there was any need to load them down with a felony charge that they would be stuck with forever.”

Hernandez broke the news to the boys himself, informing them that they would be returning to their regular classes. “We’ve weathered this storm,” he told them, “and now we’re not going to give anyone any reason to talk. We’re going to prove ourselves over and over again.” The boys went out to get haircuts and showed up at the high school the next morning. Because all four had been banned from school grounds and all school activities (they had also been grounded by their parents since mid-December, forbidden from leaving their homes even on weekends), they had seen only a few of their fellow students. They were “a little apprehensive about how they would be treated,” noted Hernandez. But the response was overwhelming. Guys pounded them on the back. Girls hugged them. Teachers shook their hands. Call rejoined the golf team and went to the district meet, shooting a 76 to win top medalist honors. Zac and one of the minors rejoined the track team and helped lead it to the district championship. And by the time summer came around, residents all over Iraan began talking about the prospects of next year’s football team now that the four stars were back.

“It feels good to finally have it all behind us, to know people aren’t against us here in Iraan,” Zac told me. “I just wish everyone else outside Iraan would forget what happened and let us move on with our lives. It’s like all these people really think we should live with this one mistake for the rest of our lives.”

The Internet, of course, was rife with messages from those who said they would never forget. Bloggers who had previously attacked school officials for letting the boys stay in school were furious that they were getting to rejoin sports teams. “Wow, kids can get expelled for drugs, weapons, or fighting,” someone commented. “Kill and torture animals, and all is well in Iraan.” One writer proposed that any school competing with Iraan “file a complaint with the University Interscholastic League that Iraan is using criminals,” and another suggested that the football team’s motto, “Fear the Spear,” be changed to “Fear the Spear, Because We Kill Deer.” Plenty of commenters warned the citizens of Iraan to lock up their children at night (“I pity the poor townfolks there when [the boys] get REALLY bored!” one declared), while many more wished the boys endless pain and misery for the rest of their lives. Wrote one: “I hope that every night they have nightmares about being lured into batting cages.”

In reality, however, the venom soon began to fade. PETA moved on to other issues: neglected sheep in Ohio, the horrors of donkey basketball at an Illinois high school. And the fact was that the boys were certainly not doing anything to set off new complaints. They’d been “squeaky clean, pretty close to perfect in their behavior,” Hernandez informed me with a chuckle. “And all of them have told me they don’t want to have anything to do with any deer ever again—not hunting them, chasing them, anything. None of our kids do. The other day, a deer was in the outfield eating some grass, and when he tried to leap away, he miscalculated, ran right into the fence, and collapsed. Some of our athletes were out there, and they ran as fast as they could to the coaches’ offices, yelling, ‘We didn’t do it! We didn’t do it!’”

Things were going so well, in fact, that Call’s grandmother, Gaile, sent Texas Monthly a letter in June asking that the magazine not publish one more story about the boys. “Since school will be in the process of beginning a new year, give these young guys a chance,” she wrote. “Another chance. Don’t keep beating the dead horse.”

But in her letter, she was unable to explain why her grandson and the others had so viciously clubbed the deer, except to write, “We all understand that messing up is part of growing up.” The truth was that plenty of people, even those who supported the boys, remained baffled by what had happened. “How do you explain why four good kids suddenly decide to do a bad thing?” Allen told me, leaning back in his chair and staring out the window of his office, which, coincidentally enough, provided him a slight view of the high school’s baseball field. “How can anyone explain it?”

When I asked Hernandez, who had made a point of spending time with the four boys almost every day of the week during their disciplinary period, if they had ever given him any insight into the killings, he paused, then finally said, “I have to admit, I brought that subject up a dozen times, and they couldn’t explain it. They’d keep saying that one thing led to another, and just like that, it was all over. I’d go, ‘But why?’ And there would be this silence. They still didn’t have an answer.”

Perhaps they will never have that answer. During my conversation with Zac, I trotted out numerous theories about what had motivated their actions that night. At one point, I asked if he and his friends were wanting to blow off some steam because their football season had just ended and they hadn’t won the big game. “It was your first free Friday night since September,” I suggested, “and maybe you and your buddies had had a few beers and got a little rowdy.”

“No, we didn’t do anything like that,” Zac said. He glanced quickly at his father, sitting next to him, and then he added, “When we got the deer in the bull pen, they started running into the fence, getting hurt, and we decided to put them out of their misery.”

I stared at him. Neither he nor Call had made any reference to a mercy killing when they’d written out their confessions for the game wardens back in December. According to Davis, the two had never once hinted during his long interview with them that the deer had been in distress before the beatings.

“Is that really what happened?” I asked him.

“Yes, sir,” he said, swallowing, and I couldn’t help but think of the scene at the end of Lord of the Flies, when one of the main characters, Ralph, tries to come to terms with the devastation he and the other boys have inexplicably wreaked on the island—wrestling with what William Golding described as “the end of innocence, the darkness of man’s heart.” I wondered if the reason Zac had created this new explanation, trying to put a good spin on the deer’s deaths, was because he, like Ralph, was genuinely haunted by what he had done.

I left Iraan late that afternoon, as the sun was setting. Allen’s secretary told me to drive carefully. “You’ll see deer crossing the highway,” she said, “and if you think you’re going to run into one, don’t swerve and try to miss it. You could run off the road and have a bad accident. Just hit the deer straight on. That’s the safest thing.”

She smiled at me. “You think I’m kidding, don’t you?”

She was not. Before I was thirty miles outside of town, I had seen a dozen deer, all of them cutting through the brush, their eyes gleaming in my headlights. One, a mature doe, looked poised to cross the highway. I slowed down, and for a moment, she stared in my direction. Then she suddenly turned and raced away.

- More About:

- Crime