This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

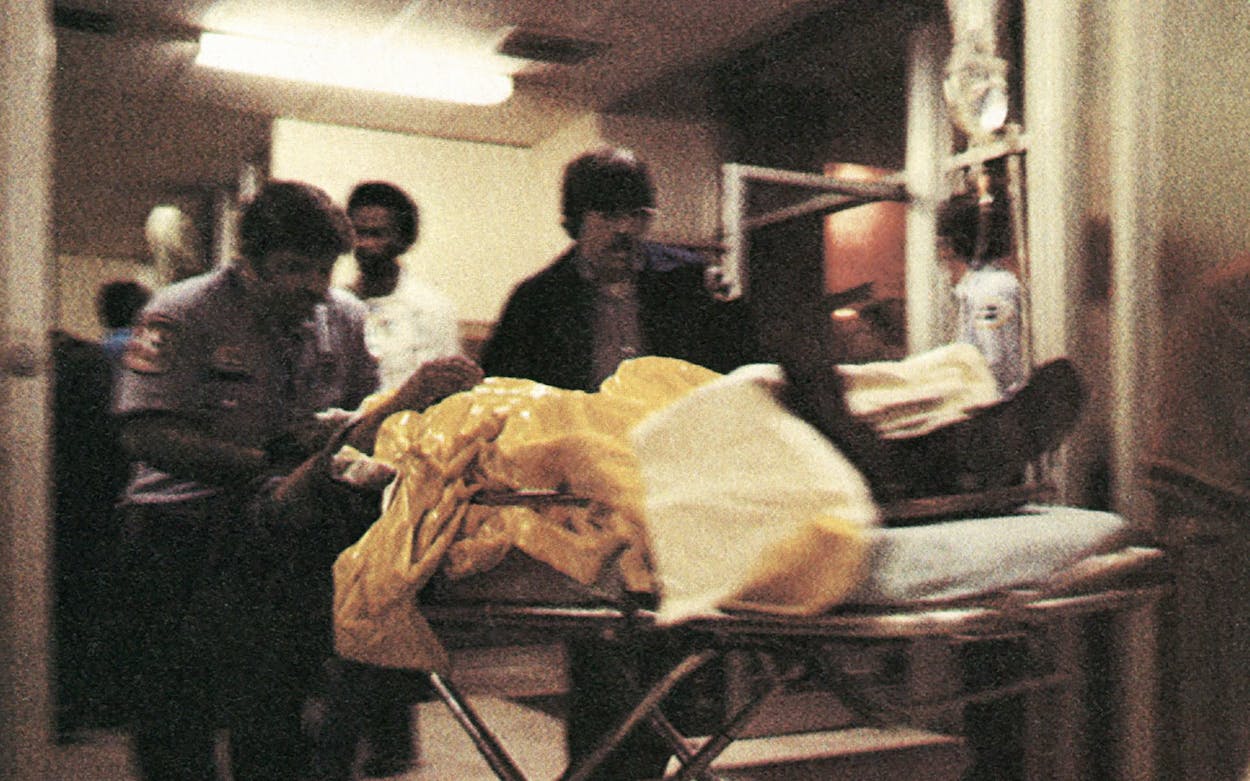

The man lying naked on the shock table has a small bullet hole in the left side of his stomach. On his upper right side beneath the skin covering his ribs, you can see a rounded lump where the bullet has stopped after transecting the abdomen and chest, ripping the diaphragm along the way. His rapidly swelling stomach indicates severe internal bleeding and makes him look vaguely pregnant. Like in the movies, the patient asks hoarsely, “Reckon I’m gonna make it?” The surgery resident in charge glances down and says, “Yeah, you’re at Ben Taub.”

Houstonians are generally matter of fact about recommending the Emergency Center at Ben Taub General Hospital. Cops, cab drivers, health workers, affluent housewives—all potential casualties in the urban war zone—will tell you, “If you’re really hurt but you can still speak, tell the ambulance driver Ben Taub.” You also hear “best in the world” and “best in the U.S.” If you ask for specifics, then you begin to hear about nationally famous, prototypal shock rooms and shock tables where they “raise them from the dead.”

Shock rooms, sometimes called trauma rooms or crash rooms, are facilities designed for the treatment of major trauma or shock. (Shock is the condition marked by falling blood pressure, a slowing of the vital processes, and deprivation of blood to the brain and other organs.) The shock room concept began to develop in the late fifties and sixties because of the increase in auto accidents and crimes of violence. Ordinary rooms were set aside in large city hospitals where the critically injured could be resuscitated and stabilized. Most major hospitals now include shock rooms as a matter of course.

Shock rooms, you might imagine, would be futuristic wonders of technology equipped to process the injured and make them whole. The main shock room at Ben Taub, however, implies not so much the technological future, as the medical past. It is a small ten-by-fifteen-foot room with institutional green tile walls. The shock table, not much larger than a stretcher, stands at the center of the room. Neither the room nor the equipment in it looks very impressive.

What is impressive in the Ben Taub shock rooms is the frequency and success with which chests are cracked. Chest cracking, or thoracotomy, is a standard surgical procedure in which a deep incision is made through the wall of the chest between the ribs. The ribs are then pulled or “cracked” open to reveal the heart and lungs. It’s said that more chest wounds were treated in Ben Taub shock rooms with greater success than were treated in the Viet Nam War during the same time span.

A key to the Ben Taub salvage rate—combined with sufficiently high levels of violence in Harris County and an Emergency Medical Service that can bring the victims in alive—is the aggressive treatment cases receive in the shock room. The Medical Center in Houston is famous for heart surgeons and heart transplants, and cardiovascular surgery is the specialty at the Baylor College of Medicine. Competition among the top heart surgeons filters throughout the Medical Center to create aggressiveness at all levels. Because Ben Taub is a Baylor teaching hospital, the shock rooms there are often the first chance for surgery residents—some future heart surgeons—to get their hand in. Their energetic approach is so effective that, according to District Attorney Carol Vance, Ben Taub “saves” are lowering the homicide rate in Harris County.

To gauge the accomplishment at Ben Taub, it’s necessary to understand that shock rooms are not operating rooms. There are two basic differences: shock rooms are not kept as sterile and general anesthetics are not used. If the patient is already in a state of grave depression, as is the case in shock, the additional depressant of a general anesthetic is potentially lethal. Even local anesthetics are rarely used on patients who are conscious, because time is more important than pain relief. The surgery performed is not definitive, but stop-gap. Think of cracking a chest as first aid.

Pete Fulano is a typical casualty about to number among the dead. Pete stops at a convenience store late at night for a pack of cigarettes and has the misfortune of breaking up an armed robbery. The robber panics and starts to shoot. He kills the store manager and Pete gets a bullet in the chest.

When the police and the ambulance arrive, Pete has lost consciousness and his blood pressure is falling fast. The emergency medical technician (EMT) in the ambulance can start IVs to try to maintain his blood pressure, but it’s like trying to blow up a balloon with a leak in it. The ambulance driver radios in to the telemetry room at the Ben Taub Emergency Center that a “chest” is coming in.

In a closet-size room in the Emergency Center another EMT takes the call. Above his desk there are four flickering TV screens for electrocardiograms and a regular television set on top of a filing cabinet. The EMT turns the sound off on S.W.A.T. and steps out into the hall to tell the head surgery resident. They return to the telemetry room where Pete’s erratic heartbeat is now flickering across one of the screens. As they watch the heartbeat, the voice crackles in over the radio giving Pete’s blood pressure and pulse.

The atmosphere in the Emergency Center changes perceptibly as word is passed that a chest is coming in. There’s the tension and excitement of people keying up to perform at full capacity. A nurse walks down the hall to check the main shock room to see that it’s clear and then sticks her head in at the x-ray technician’s office. “Better get ready,” the nurse says. “We may crack a chest. One’s coming in now.”

“Which team is this?” an intern asks the nurse as she heads back down the hall. “B,” she says and smiles. “We get this one.”

Pete’s blood pressure is almost down to zero by the time the ambulance backs up to the Emergency Center loading dock. The blood filling up his chest is collapsing his lungs and breathing is difficult. Pete, in the lingua franca of emergency centers, is “cratering.” A bell rings in the shock room to notify Team B when the stretcher hits the loading dock. An orderly and EMT wheel the stretcher past the registration desk and the staring faces and down the hall toward the shock room. The nurse is holding the door open when they arrive.

Inside the shock room, Team B (the nurse, two residents, and an intern) is waiting. Residents, interns, and nurses are divided into three shock room teams that handle cases on a rotating basis, or simultaneously if there’s more than one case. A medical student, x-ray technician, and an aide are also there.

As Pete is transferred from the stretcher to the shock table, a resident starts pulling and cutting his clothes off. The wound doesn’t look bad: a small, red pucker of flesh.

“We gonna boogie with this one?” an orderly asks, wondering if they’ll take Pete to the operating room upstairs for surgery.

“Blood pressure’s zero,” the nurse calls out.

“This man is dying!” the resident barks. “Get those IVs going!”

The intern and medical student plug the IVs into the veins in Pete’s hands, the nurse injects an antibiotic, and a resident draws 30 ccs of blood for cross matching and lab tests. A patient has approximately four minutes after blood pressure falls to zero before oxygen-starved brain cells begin to die. If oxygenated blood gets to the brain within five minutes, there is minimal damage. If it is seven minutes, the patient probably won’t be able to do calculus. After ten minutes, the patient spends the rest of his life in a nursing home. It has happened that patients are resuscitated after brain death occurs. In such cases, they are neurologically, legally dead, and the heart-lung machine is switched off.

Ben Taub shock teams don’t stop to calculate the four minutes or worry about the amount of brain damage a patient might suffer. To do so would be to lose the aggressive edge, to lose lives.

A tube attached to a small black bag is run down Pete’s throat. One of the residents pumps the bag slowly to maintain respiration. Outside, a knot of staff people has formed at the door to watch. “Gonna crack a chest” is the word. Extra people have edged into the room for a better view and the room temperature rises noticeably from the crowd and the tension until the nurse looks up and sees there are sixteen people in the room. “If you are not on Team B,” she intones, “Please get out!”

In the meantime, the head resident has shaved Pete’s chest and swabbed him with amber-colored antiseptic. After putting on rubber gloves, the resident takes up the scalpel. With his left hand, he feels for the space between the ribs just below Pete’s left breast. He positions the blade above the space and for a moment everything is still. The resident’s elbow goes up, his shoulder down, and in one decisive movement, the blade is through and drawn down between the ribs. The resident wedges his fingers into the incision and pulls the upper and lower halves of the rib cage apart until there is a slow cracking, like the sound of a chicken being disjointed. Part of a lung pops out and the blood—what doesn’t spill out of the cracked chest like paint out of a can—is sucked up to be recycled by the autotransfusion device. But for Pete’s body lying out exposed and his bare feet, the shock room could be a butcher shop and Pete a side of beef.

To hold the chest open, the head resident inserts a chest retractor—a small, stainless-steel cousin to a car jack—between the ribs and cranks it open. He clamps off the descending aorta to prevent further loss of blood in the abdomen and to maintain blood pressure and volume for the heart and brain. The aorta, as big around as a fifty-cent piece, is the body’s largest artery. The resident then picks up the shiny white, gristlelike sack that contains the heart and slits it open. He pulls out the dark, stringy blood clots and hunts for the puncture. After suturing the puncture, he reaches in, takes Pete’s heart in his hands, and pumps.

The leak patched, the IVs and transfusions going, Pete’s blood pressure will begin to rise. Though in critical condition, he is past the immediate danger and can be moved to the operating room upstairs where the surgery will be completed. Within two weeks, he’ll be back at home.

Are the risks of cracking a chest too high? Is it cure or kill? The survival rate is 95 per cent for stab wounds and 85 per cent for gunshot wounds. Twice as many patients undergoing thoracotomy at Ben Taub have been shot as have been stabbed. Seventy per cent of the patients with blunt trauma (beatings and car wrecks) survive the injury. From one point of view however, the operation is risk free. A man (and 95 per cent of the victims are men) with penetrating or blunt trauma to the chest and zero blood pressure has virtually nothing left to lose; his very condition is implied consent for the operation.

The Monday night I first went into Ben Taub, I was prepared for the blood and gore; I wasn’t prepared for the strange conjunction of pain and humor. A man on the shock table had an inch-long cut on the side of his chest. Since he was awake, I assumed he’d been given a local anesthetic. The head resident began to probe the wound with a metal clamp about the size of ice tongs. As the clamp entered the wound, the patient began to scream, “Good God, what are you after?” over and over again, and finally jackknifed his feet straight over his head. An orderly and medical student held the man’s legs, and the probe continued until the final diagnosis (“Guts up in his chest”) was made. The man was left panting with relief on the shock table while the resident conferred in the hall with the surgeon from the operating room upstairs. The surgeon stepped back into the shock room to give the patient the verdict: “We have to operate on your belly,” he said.

“While I’m awake?” the man asked. Everyone laughed.

The alternative to laughter is despair. Shock teams watch patients cry, fight, and beg to be knocked out; they see more suffering on a Saturday night than most people see in a lifetime. Such intense and prolonged pain exacts an emotional response from the observer. It also makes the normal appear incongruous and the most commonplace statement sound absurd. The result is not callousness but levity, which unlike grief, allows you to go on.

The rest of the Emergency Center is not exactly a relief from the shock rooms. During peak hours, it looks nothing less than a battle station. Two large waiting rooms are crowded with people, long lines form before four registration windows, and the long main hall within the Emergency Center is lined with sick and injured people. No one is happy and some people are obviously in pain. It is not unusual to hear agonized screams from within the treatment areas or to see a patient covered with blood from a minor scalp laceration stroll casually down the hall. The drunks bawl and the acutely disorganized psychotics chitter. People become angry because their crisis is a routine matter to the emergency staff or because they’ve been separated from their family. In the waiting room, guns fall out of the hats of fight participants waiting to conclude their business. At a glance, you can tell that this isn’t the country club crowd. Only 12 to 15 per cent of the patients are full paid; the rest have some sort of indigent status. Economically, as well as physically, the people waiting are marginal survivors.

On the average, 250 patients are seen every day in facilities designed for a maximum of 200. Some days the traffic is heavier. Payday Fridays are always bad, and some staff members say it’s worse when the moon is full. On a recent full-moon Friday thirteenth, there were 42 shock room cases alone. George Washington’s birthday brought in 410 patients, and a big rock concert in an auditorium where there’s booze to go with the Quaaludes always pushes up the number of ODs. The worst times are the hours from 5 p.m. to 8 p.m. on Friday and from 11 p.m. to 3 a.m. on Friday and Saturday. As many as 11 shock room cases have stacked up at a time.

In addition to the shock room cases, the shock teams see and treat all other patients as well. Complaints range from a man checking in at 3 a.m. because of sleeplessness (“I couldn’t sleep, anyway I tried”) to a woman with a billiard ball stuck in her vagina. For cases where the residents need help, there are doctors from all surgical and medical specialties on call within the hospital who can be in the shock room in three or four minutes.

Given the conditions, morale in the Emergency Center is incredibly high. Everyone from the head resident to the woman sterilizing equipment in housekeeping knows his or her job is important, and a self-generating energy of excellence is palpable. Staff members are proud of their work and quick to say their ER is the best. When I asked a Ben Taub public relations officer about Ben Taub being best, he demurred, saying there are much larger, better equipped ERs that did a very good job. The high morale he attributed to everyone having to work at full capacity to make up for understaffing and overcrowding.

Staff members at the Emergency Center not only take pride in treating medical problems but also in treating patients as people. If staff and patients don’t necessarily share class backgrounds, they do have age in common (average age for staff members is thirty; the majority of trauma victims are younger than forty), and communication is surprisingly good. According to one nurse, the only group not shown much sympathy are the kids who OD. “We let that experience be as unpleasant as possible,” she said.

There is concern, however, that the patient’s psyche doesn’t receive enough comfort in the shock room. To be stripped, have blood drawn, IVs started, a Foley catheter inserted, vital signs taken, and your stomach pumped all within ten minutes can’t be very pleasant. For the patient, disoriented, in pain, often drunk, it is a demoralizing experience to be spread naked on a table and surrounded by a group of strangers shouting, pulling, and poking. The shock team’s behavior is not malicious but is prompted by the urgency of the situation. As a concession to the psyche, it’s been suggested a notice for patients be painted on the ceiling over the shock table: “This is not hell. This is Ben Taub.”

I doubt a sign on the ceiling could convince a patient he wasn’t paying for sins. My first night at Ben Taub, a thirty-year-old man with a bad scalp wound was brought into the shock room. His head and torso were covered with blood. A registration clerk had followed the stretcher down the hall to fill out his record card. As he is moved from the stretcher to the shock table she is yelling at him, “What is your Social Security number? Joe, what is your telephone number? When were you born?”

While Joe undergoes this torment of apparent trivia, he is stripped and the shock table is tilted so that blood rushes to his head. A resident pours a bottle of hydrogen peroxide into his hair, which immediately bubbles into a strawberry froth. The clothing clerk is tugging at a ring on one of his fingers after having collected his clothes. Joe turns his head to one side and throws up on the floor.

“Lone Star or Pearl?” someone asks.

Seven people are working around the table. They wipe up the blood and vomit and discover a bruised, possibly broken hand. When one of the residents picks up the hand, Joe winces and pulls back. Pulling back from pain is only normal; it is why patients in shock often regress psychologically.

“Hurt your hand, Joe?” the resident says. “Where’s it hurt?” No answer. Joe expresses the pain but doesn’t describe it. Like most people accustomed to arbitrating differences with guns, knives, and fists, Joe isn’t particularly articulate. He doesn’t say, “Third finger to the left, middle joint.” The resident, to cross psychological and class barriers and establish a line of communication, can manipulate the pain to determine quickly where and how a patient has been injured (which is not always obvious when he’s covered with blood).

In the meantime, the resident with the peroxide has shaved out a patch of gray scalp around a purple gash on the top of his head. “Hey Joe, what happened to your head?” the resident shouts. “Fell down,” Joe answers. Everyone thinks that’s funny and laughs.

“Hey Joe, can you pee for us?” an intern yells. “Hey man, we need some urine. Can you pee for us or do we have to stick this in your penis?” He whacks Joe lightly on the belly with a half-inch-wide plastic tube. No response. The intern puts down the tube, gets out a Foley catheter, which is not nearly so big, and says with regret, “I sure wish you could pee.”

With what sounds like bravado, Joe has begun to repeat, “I’m OK. I’m gonna be all right,” as if to reassure the shock team. Before anyone can respond and reassure Joe, the x-ray technician in her protected booth yells, “Shooting!” and everyone runs out of the room. Confused, I’m left alone with Joe. When no one answers, his bravado changes quickly to resigned doubt: “I’m gonna live?” or—reflective pause—“I’m gonna die?”

After a few seconds, everyone files back into the shock room. One of the residents who, like everyone else, dropped what he was doing and ran out in the hall, explains to me, “X-rays—gets your gonads after awhile. Better run when they shoot.”

As it turns out, Joe lives. Other than a sore head and hand, he probably won’t remember much. Possibly he’ll come back; one out of five shock room cases do. As much beer as he’d drunk, it’s unlikely that Joe even felt that much pain.

Once inside the center, it’s easy to lose track of time. There are no windows to show that the sun is setting or that it’s dark. There’s only the gradual movement of the long line of people waiting and the arrival of the ambulances. Nor is degree of exhaustion an indication of time; each new crisis starts the adrenaline flowing until the night becomes one long arc of adrenaline. The shifts change at 4 p.m. and 11 p.m., and the people who come on at 11 p.m.—the real night people—are saying good morning and exuding the recent contact with sheets and pillows associated with a new day.

During the night, the ambulances brought in the gunshot wounds, the stabbings, the beatings, and the auto accidents. One man had been shot so often a bullet, of its own accord, fell out on the shock table. Another man thought he’d been stabbed but had actually been shot. A woman being sewn up in the suture room was hysterical; the police had found her running through a parking lot naked to the waist and with a bad gash in her arm. A young girl, pathetically thin with dirty bare feet, was caught running in the traffic. Whenever she saw me, she would motion me over to whisper confidentially that she was the one who’d “opened the door on it,” she was the one who “knew.”

I asked two different men who were coherent why they’d been shot or stabbed. They looked at me without comprehension. It wasn’t that they didn’t understand me. Shootings and stabbings were things they didn’t question.

At 4 a.m. I’d been in the Emergency Center fourteen hours, but I kept putting off my departure. I think I felt the same as the staff members who I’d noticed linger on at the end of their shifts. There’s not only a feeling of excitement in the Emergency Center, but also one of reassurance. After hours of watching stretchers come in with the wounded, you begin to feel you’re safe underground in a bunker with the war raging on above.

Getting the Treatment

Compared to the front lines atmosphere of Ben Taub, the emergency room at Dallas’ Parkland Hospital seems as sleek as an airport.

If you have an accident in Houston, go to Ben Taub. If you have an accident in Texas, have it in Dallas. The Emergency Suite at Parkland Memorial Hospital is to emergency wards what DFW is to airports; easily the largest ER in Texas, if not the country, it is also one of the best equipped.

Enlarged and remodeled in 1973, Parkland’s ER covers 32,000 square feet (“larger than a football field”) of nurse-white tile and linoleum. Separate treatment areas for Surgery, Medicine (minor and major), Ob-Gyn, Psychiatry, and Pediatrics are open around the clock as are the blood bank, pharmacy, lab, and radiology department. Red, green, and blue signs overhead in the long white corridors direct patients to the different areas, and, as in the airport or on an expressway, there are more wrong turns than right.

On an average day, 485 patients follow the signs through the corridors. During a flu epidemic, 750 patients were cared for in one day without straining the system. Seventy-six individual treatment rooms scattered throughout the Emergency Suite create a mazelike atmosphere but provide for a patient privacy, a prime consideration at Parkland. Parkland, unlike Ben Taub, is able to close the door on the individual Greek tragedies.

To ease disadvantages of size and keep patients from getting completely lost, the staff (three shifts of 150) includes a patient coordinator, who acts as patient advocate to the staff, and a discharge planning nurse, who sees that patients actually understand what the doctor tells them about their condition and how to care for it when they leave. Depending on the shift, there are twelve to seventeen physicians on duty in the Emergency Suite.

As to Emergency Medical Services, Parkland is the prototype in the U.S. for delivering health care to the community when and where trauma occurs. Seventeen ambulances located throughout Dallas respond to emergency calls in an average of 4.96 minutes. The ambulances, operated by the Dallas Fire Department, are each manned by two EMTs trained by the University of Texas Health and Science Center. Following instructions of Parkland physicians via the emergency telemetry system, EMTs in the ambulances can start intravenous fluids, read and monitor electrocardiograms, give electrical shock treatment for heart cases, administer drugs, and intubate patients to secure an airway.

Unlike Ben Taub in Houston, there isn’t one main shock room at Parkland but six fully equipped trauma rooms. The most famous trauma room, however, the one in which President Kennedy died, no longer stands. When Parkland remodeled in 1973, the National Archives paid a token $1000 for the room, and federal employees arrived late at night to remove the equipment and jackhammer the tiles off the floor and walls. The room and its contents are thought to be stored in boxes somewhere in Fort Worth.

John Davidson is a freelance writer living in Austin.