This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

When Malcolm Royse hired on at Carmel Apartments as maintenance man, the job sounded almost too good to be true: $650 a month plus overtime and a rent-free two-bedroom apartment. Located in Hurst, a bedroom community near Fort Worth, Carmel wasn’t half bad—once Malcolm got used to the rumble of the freeway. As it turned out, the job was too good to be true. During the six weeks that he worked there, Royse found forty roof leaks and evidence of a number of electrical fires. At least eighteen apartments were in such bad repair that they were uninhabitable. Carmel had already been written up frequently for violations of the Hurst housing code, and Royse doubted if even 10 of the 206 apartments were in compliance with the law. Tenants kept complaining about the air conditioning—and with good reason. The main chill-water line needed to be replaced, but the penny-pinching management just kept patching it instead.

Maybe Carmel was a bargain—a one-bedroom unit rented for $235, which was $15 lower than the average rent in Fort Worth and Dallas—but Malcolm didn’t think that excused the shoddy condition of the apartments. He worked like a Trojan, unclogging toilets and fixing soggy ceilings, but he never got the overtime pay he was promised. When he told the manager he was quitting, she told him he was fired. She threatened to evict him, but he stayed on as a paying—and vocal—tenant. He emerged as a leader of the disgusted tenants during a long hot summer of skirmishes with Carmel’s aloof management.

Management eventually made a few repairs, but it wasn’t long before the air conditioning was on the blink again. During a heavy rain the ceiling of one unit caved in, soaking a baby in his crib. One woman returned from her job to find her apartment ankle-deep in water from a burst pipe. A picture window popped out one night, strewing shattered glass all over a tenant’s dining room. And then raw sewage and bits of toilet paper started backing up into the swimming pool.

That’s when the tenants put up big signs in the picture windows fronting Highway 121. They said: DON’T MOVE HERE. BAD MANAGEMENT.

The New Wastelands

Similar manifestations of tenant outrage are beginning to be heard all over Texas, and this time the rumblings are not just from the wrong side of the tracks. The poor and the ethnic minorities have a long tradition of making do with inferior housing. Now the middle class, too, is learning what it is like to live in apartment slums, and they don’t like it one bit.

There are several reasons for the growth of the apartment wastelands: the continuing mobility of the work force, especially into the Sunbelt, where so many Yankee corporations are coming south to roost; the prohibitive cost of home ownership; the soaring costs of apartment construction and upkeep; the increase in short-term speculation in apartments; tax codes that benefit the speculator; and the growing phenomenon of absentee ownership.

All these factors working simultaneously can produce a town like Addison, a community so new that its streets are still uncharted on Dallas-area maps. Ten years ago, Addison, at the end of the North Dallas Tollway, had a population of six hundred. Today it houses seven thousand people, mostly transients, 98 per cent of them jammed into apartment units distinguishable only by the random airplane plant hanging from a tiny balcony or the smoldering hibachi on a miniature patio. A city councilman estimates that the town has only thirty single-family dwellings and fewer than two hundred children.

Addison is so new and so sterile that it seems to be wrapped in cellophane, and yet many of its granddaddy apartments, built as long as seven or eight years ago, have already deteriorated into Sunbelt slums with rotting floors, sewage backups, leaky roofs, buckling pavement, mildew, roaches, and rats. Addison’s growth-and-decay cycle is running on fast forward, like one of those nature films in which time-lapse photography induces a tulip to sprout and bloom and wither in just a few seconds.

The typical Addison resident moves frequently. If one apartment begins to deteriorate, he breaks camp and heads for another. It is a rootless, no-deposit, no-return kind of existence. Very few people think of Addison as “home.” And yet, with the average price of a new house beyond the reach of 75 per cent of the American populace, more and more people are moving to apartment zones—it is too charitable to call them communities—like Addison. In Dallas more than half the population now rents, and tenancy is expected to top 60 per cent in the next few years. Many middle-income Texans who only a short time ago could afford a house are facing up to the prospect of permanent membership in the tenant class. Of course, there are people who prefer to live in apartments because a well-run complex is worry free. But first-rate apartments are getting harder and harder to find.

With building costs rising one per cent a month, it is easy to understand why an apartment can fall to ruin. Most builders have no choice but to cut corners. Brick lost an inflationary battle to stucco and wood siding some time ago. Now the basic apartment has a particle board exterior. Jack Craycroft, a prominent Dallas architect, quotes a builder who lamented, only partly in jest, “I’ve been tempted to put up signs saying ‘Please don’t let your dogs eat the buildings.’ ” But lack of upkeep is more at the heart of the problem. Under normal conditions, apartment owners want to keep their property in good condition because it holds its value better that way. But with high inflation, owners start deferring much-needed paint jobs and repairs.

Maintenance also goes downhill when short-term speculators get hold of an apartment complex. Speculators often buy distressed properties, do some quick cosmetic improvements on the exterior, and then resell them for a quick profit.

A veteran apartment manager who worked for some quick-buck artists in Dallas says, “When I spent money to have the apartments exterminated for roaches and bedbugs, I was reprimanded. I was told to fill the apartments with warm bodies and to rent the units as is.” Apartment buildings are sold not so much by the condition of the property as by the gross annual rent revenue. Hence, the speculators wanted to fill the apartments quickly so they could claim on their financial statement that the building was fully occupied.

Latter-Day Gold Rush

To the uninitiated, an apartment building looks like a surefire business investment. You select a likely building property, keep it in good repair, carefully select your tenants, raise rents sufficiently to keep up with inflation, and you have a steady source of income for decades. Indeed, there are mom-and-pop landlords making a good living in just that way. But for the builders and speculators, apartments are a boom-or-bust business. The demand for units leads to high occupancy and a rapid rise in rent, often followed by overbuilding and then a slump in occupancy during which rents stabilize and a lot of investors lose their shirts. “From 1971 to 1975,” claims one Dallas broker, “you literally couldn’t give an apartment building away for the price of the debt against it.” In 1975, an estimated 40 to 45 per cent of Dallas’s apartment buildings reverted to lending institutions or were in some form of receivership because the owners couldn’t meet their mortgage payments. With occupancy rates in major cities ranging from 95 per cent upward, it is now once again a seller’s market in Texas, and with its good business climate, relatively low prices, and rapid growth, Texas is a plum real estate market. Investors from within and without the state are putting their money in apartment buildings as an ideal hedge against inflation and a good tax shelter.

The federal tax code as applied to low-income housing actually encourages the rapid turnover of apartment property. When an investor buys a building in need of rehabilitation and then rents it to low-income tenants, he can legally write off the cost of rehabilitation expenditures on an apartment building in only five years. Let’s say a wealthy doctor buys such a building for $500,000 and spends $500,000 fixing up the units. He will probably pay 10 per cent of the total cost and borrow the rest from a savings and loan or an insurance company. For a cash outlay of $100,000, he can claim depreciation deductions of slightly over $100,000 a year during the first five years of ownership. All the interest payments on his loans are tax deductible, and so are the maintenance costs. Five years later, he slaps some fresh paint on the apartment exterior and sells it to another investor for, say, $1.2 million. Because of inflation the apartment has actually appreciated rather than depreciated in value. And as long as the doctor holds the property for more than a year any profit he realizes on the sale of the property is treated as a long-term capital gain and taxed at only 40 per cent of the rate he would have paid on his “ordinary” income from removing gallstones and tonsils. Meanwhile, the new owner is starting the depreciation process all over again. Only this time the building is depreciated for over $1 million in tax deductions.

The most aggressive investors in Texas apartments right now are Californians, who have seen property rates in their home state soar into the stratosphere—in part because Canadians and other foreigners escaping high inflation and tax rates in their home countries have invested so heavily in California real estate. The rent revenues on Texas apartments run about 40 per cent less than those in California, so purchase prices are correspondingly lower. In addition, the investors seek refuge from strict California laws—building codes, pollution controls, tenants’ rights, and rent control.

Many out-of-staters get into Texas apartments through syndications. A corporation, acting as a general partner, accumulates a portfolio of apartments and then sells an interest in the apartments to investors, who become limited partners. The investors may never even see the apartments. The day-to-day operations are handed over to a management company, which usually takes 3 to 6 per cent of gross rental revenue.

The quality of management varies from excellent to awful. Many tenants never even know who owns their apartments. Kathy Cox, president of the Dallas Tenants Association, is convinced that out-of-state and foreign investors, who now own about 10 per cent of Dallas-area apartments, make worse landlords than local owners. “They are totally impersonal. They think of a complex as an investment, not as a place where people live,” she said. “They raise rents faster than local owners do, make fewer repairs, and will turn a tenant out into the street if he’s two days late with the rent.”

A Dallas attorney whose firm has represented sellers of fifteen different buildings in the last two years told me that not a single one of the purchasers was a resident Dallas buyer. One large apartment complex was sold to a British Columbian limited partnership with a Netherlands Antilles corporation as the general partner. The principal shareholders in that corporation were Indian nationals. “Now, how do you penetrate that to find the responsible party?” the attorney asked.

The Many Complexes of Kurt Bromet

Currently one of the biggest out-of-state buyers in Texas is Kurt Bromet of Beverly Hills, who immigrated to the United States from Germany before World War II. Tanned, intense, sixtyish, he’s an old-school my-handshake-is-my-word workaholic businessman, capable of making quick and dramatic decisions. When West Coast real estate prices skyrocketed in the mid-sixties, he sold literally thousands of California apartment units. Later he shifted his focus to Dallas, where he bought his first apartment complex in November 1976. He homed in on large complexes from three to ten years old, preferably buildings that were going cheap because they were in need of major repairs. In two and a half years, Bromet’s company acquired more than 12,000 apartment units in Texas—a “staggering number,” said a Dallas real estate agent who has sold him some buildings. “Few people could do what he has done in such a short time. He makes decisions snap, snap, snap,” the agent said in profound admiration.

Bromet’s properties are in Dallas, Fort Worth, Austin, and San Antonio. He has avoided Houston because, as Bromet’s young chief executive officer, B. Thomas Mann, explained, “Houston has such a volatile market. There’s no zoning and the construction is inferior.” Bromet has 6000 units scattered throughout Oklahoma, Florida, Louisiana, Georgia, Tennessee, and North Carolina, and he still holds 1800 units in California. His Texas acquisitions have slowed, Mann said, because he can no longer find the bargains that were available a couple of years ago. Bromet still resides in California (when he visits Texas he lives a spartan life in one of his apartments), but his company headquarters is now in Dallas, and both his acquisitions company (K. B. Investment Corporation) and his management company (Bromet Property Management Corporation) operate under Texas charters.

Bromet is not a syndicator like so many of the big California buyers, but his operation is similar to a syndication. Within sixty to ninety days of purchasing an apartment building, he sells it, retaining a lien, to a passive investor (often a Californian), then leases it back. He generally guarantees the investor a fixed minimum return. Bromet retains the right to manage the apartments on an “incentive” basis; that is, his company absorbs the loss if the apartment fails to break even, but if the apartment does well, the management company keeps the net profit over and above the investor’s guaranteed return. The investor usually sells his interest in the complex after seven or eight years.

But through all this, what happens to the apartments themselves? “I personally know of complexes into which Bromet has put $300,000 to $400,000 in repairs and improvements,” said Jed Dodson, past president of the Dallas Apartment Association. And yet Kathy Cox and the Tenants Association nominated Bromet as the worst landlord in Dallas. Not only had he received the highest number of tenant complaints, but he is also virtually impossible to complain to. Typically, when an irate tenant makes a complaint to Bromet’s management company, he never gets beyond the receptionist. It’s as frustrating as dealing with Ma Bell. Bromet’s glossy company brochures advertise that his vast holdings in each city benefit from central management and central purchase and storage of supplies. But his critics say that no company can do a first-rate job of managing more than a thousand or two thousand units. Here are some complaints from a few of Bromet’s tenants:

• One woman in Austin received what she described as a substantial out-of-court settlement from Bromet’s company after she suffered carbon monoxide poisoning from a malfunctioning pilot light. She was so incensed by what she considered to be Bromet’s cavalier treatment of her that she has enrolled in law school to study tenants’ rights.

• During the summer of 1978, the air conditioning was on and off at a Bromet complex in South Austin. Ron Shortes, the University of Texas students’ attorney, was successful in getting rent rebates of up to 25 per cent a month for student tenants in an out-of-court settlement. Shortes interpreted the situation as more than an inconvenience. “A lot of people scoff and say air conditioning is not a big deal, but in this complex temperatures reached more than a hundred and fifty degrees because of no ventilation,” he said. There were other considerations besides health: two women who had opened their windows and front door to catch the summer breeze were raped by an intruder.

• Two widows who lived in a Dallas-area apartment complex that rents primarily to the elderly are suing Bromet Property Management, an apartment manager, and a maintenance man for several million dollars. In their petitions, the two women—they weren’t roommates and weren’t acquainted at the time—allege they were raped by a maintenance man who gained entrance to their apartments on the pretext of doing repairs. One of the widows said that when she told the apartment manager that she had been assaulted, the manager insisted, “It’s all in your mind. I won’t tell anybody about this if you won’t.” The maintenance man was never indicted, and in its answer, the company denies all allegations.

Part of Bromet’s problem is that he acquired apartments in Texas so fast that he didn’t have time to concentrate on hiring and training good employees. “K. B. was growing so fast that we couldn’t get experienced help,” said Mrs. Bob Campbell, who worked during 1978 as a leasing agent, office manager, and then leasing director for Bromet in Dallas. “It was not unusual for a Bromet manager to be switched from complex to complex five or six times a year. An inexperienced manager would get into trouble at one complex and K. B. would say, ‘Well, let’s try her at a smaller complex.’ ”

Early this year Bromet reorganized his entire staff. Tom Mann, who was brought in as the new head of the Bromet companies, says that about two hundred of Bromet’s five hundred employees were fired. “We had some bad managers,” he said. “We will not deny that. When you grow as fast as we have, it’s hard to keep up with growth. Bromet Properties is a big ship and it takes time to turn it, but we’re at least sideways now and turning in the right direction.”

By the summer of 1979 the Austin Tenants Council was reporting some improvements in Bromet’s Central Texas apartments, but there were still problems in North Texas. More than half a dozen organized tenants’ protests were fermenting by the end of the summer.

The Tenants’ Revolt

A closer look at the Carmel apartments brouhaha helps explain just what it takes to provoke apartment dwellers—a notoriously quiescent lot—into action, and what kind of concessions, if any, they can wrench from management by protesting. It wasn’t just the physical conditions that were frustrating at Carmel, but how the complex was run. As though she were regimenting a battalion instead of running an apartment, the resident manager was always making up new rules—and then changing them.

At one point she banned children from the adult pool area. In one respect it was a logical edict; kids frequently urinate in the pool, so the water requires an extra dose of chlorine, which the adults don’t like. Kids make a lot of ruckus and splash people, too. But the manager wouldn’t even let the children stop at the adult pool to talk with their parents. Instead they were segregated in their own pool, which was at the west end of the complex—a five-minute walk away—and unguarded to boot. She further decided that all people with children should pack up and move to the west end of the complex near the kids’ pool, while the singles consolidated in the east wing. A rumor spread that for this inconvenience each tenant would pay a $50 relocation fee. Anyone who refused to move would be evicted.

The final blow was when the manager got into a squabble with two of the most popular tenants, Steve Ledbetter and his wife, Jan. Steve worked days for the Hurst Police Department and nights as a security guard for Carmel. The tenants decided to have a mass meeting when the manager fired Ledbetter and then gave the couple an eviction notice.

At first she said she would attend the meeting, but when she heard that the press had also been invited, she changed her mind and went so far as to lock the gates to the adult pool area, where the meeting was to be held. Instead, about fifty agitated tenants gathered in the warm evening twilight on the grass between two wings of the apartments. They were a good cross section of Carmel residents—students from Tarrant County Junior College, secretaries who worked in nearby Fort Worth, a feed store clerk, two roofers, a used car salesman, a data processor, a technician in a chemical plant, housewives, and kids.

Erstwhile maintenance man Malcolm Royse, who fancies himself something of a community organizer, thought the meeting had a nice feel to it. Tenants were getting to know one another as they took turns telling their personal tales of sewage backups and ceiling leaks. Some of the tenants wanted to launch a rent strike right then, but they were counseled against it by George Stone, a housing consultant and head of the Texas Tenants’ Rights Association, a new statewide advocacy group for apartment dwellers. Most of the Carmel people were not even sure whom they would be striking against. Stone explained that the complex was owned by Kurt Bromet and other California investors who were in it for the tax break.

“They don’t care about us. We can go to the devil,” one tenant complained.

From the balcony above, an excited voice announced, “Channel Eight television wants to know how long we’ll be out here. They want to film us.”

“We’ll be here all night long,” thundered the used car dealer to scattered whoops and applause. “We’re gonna get some action!”

Not surprisingly—apartment dwellers are an easily distracted bunch—the first blush of tenant outrage had faded a bit by the next evening. George Stone, who works in Fort Worth, had made a date to give some of the Carmel people a rundown of tenants’ rights. Only Malcolm Royse appeared. But Stone, low-keyed and patient, was pleased to see him. They sat together at a long table in a deserted church meeting hall, and Stone began to arm the young man with the basic facts of tenant law.

Texas has never been strong on tenants’ rights. Traditionally, if a landlord refused to fix the plumbing or the hole in the floor, a tenant could only vote with his feet. Then, in 1978, the Texas Supreme Court in a landmark case ruled that rental property must be fit for human habitation. This was a great leap forward for Texas tenants. It tilted the balance of power enough in the tenants’ direction that the Texas Apartment Association, the landlords’ lobby, has abandoned its opposition to a state habitability law and supported a mild compromise bill that was passed by the Texas Legislature in the spring of 1979.

“The law gets us about halfway to where we ought to be,” Stone told Malcolm. It offers legal recourse when conditions in an apartment “materially affect the physical health or safety of a tenant”—that is, for the really bad problems. If the landlord doesn’t “make a diligent effort” to repair major defects “in a reasonable time,” the tenant can take him to court and force the repairs or get a reduction in rent. Stone thought some of the conditions at Carmel might well come under the habitability law.

Stone explained that he had advised against a rent strike at Carmel because the new law prohibits them. But, he pointed out, the new law also prohibits the landlord from retaliating through eviction or rent increases against a tenant who has sued for repairs. Nor can a landlord personally evict a tenant. He must get a court order that can be enforced only by a constable or a sheriff.

Through lease restrictions, a landlord exercises broad powers over where and how a tenant lives. Fair housing ordinances in most cities prohibit discrimination against tenants on the basis of race, religion, or sex. But beyond these guidelines, it’s the landlord’s choice. According to Stone, the most common complaint in Texas concerns the many apartments that set some arbitrary age limit on children or refuse to allow children altogether. Because of this trend, Stone said, families often have to settle for less desirable apartment complexes. The Greater Dallas Housing Opportunity Center has come down on the side of the families and is trying to extend the city’s fair housing ordinance to children.

Stone loaded Malcolm down with brochures and sent him back to Hurst on his motorcycle. The next day, Carmel tenants held a second meeting, this time by the children’s swimming pool. Things were moving right along. A short TV news item on the Carmel revolt apparently had gotten the attention of Bromet’s company. Within 24 hours of the newscast, the manager had quit her job, and Bromet Property Management had added a third maintenance man to the Carmel crew and dispatched repairmen to work on the air conditioning.

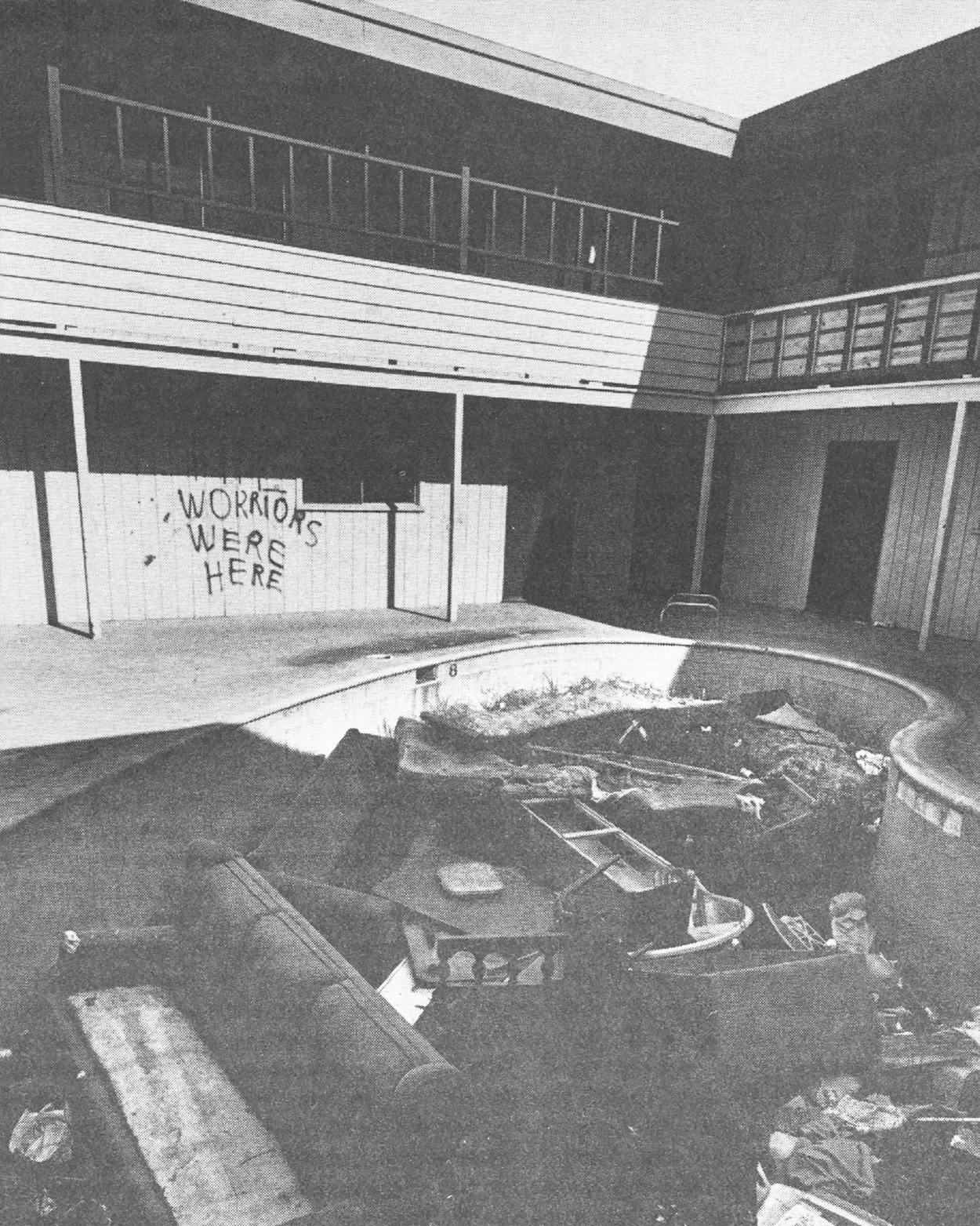

The tenants were pleased about their victories, but Malcolm feared that they had already lost their momentum. “Do you think that all of a sudden everything is going to be fixed up here?’’ he asked. “You quit bitching and that’s all the repairs you’re gonna see.” They voted to put together a list of demands to present to the new apartment manager. It was duly prepared and handed over to the Bromet bureaucracy, never to be seen again. After this things started going wrong again—the caved-in roof, the broken water pipes, the raw sewage in the swimming pool—which prompted the DON’T MOVE HERE, BAD MANAGEMENT signs.

The signs encouraged Bromet’s company to fire the supervisor in charge of Carmel and to bring in a whole new set of maintenance men. Both swimming pools were closed by the Hurst Department of Health. Shortly thereafter Malcolm Royse moved to another apartment complex to work as a handyman.

From Bad to Worse?

Next year or the year after that, a new group of tenants will probably band together to try to get some improvements made at Carmel. There’s a good chance that none of the veterans of the Revolt of ’79 will be around to offer advice. George Stone, whose previous experience is with farm workers, says part of the frustration in organizing tenants is that they never stay in one place long enough. “But one of the main reasons they don’t,” he said, “is that they are fleeing problem apartments. The landlords don’t care about high turnover. They just get more security deposits that way.”

The future of the tenants’ movement in Texas depends to some extent on how bad the housing situation becomes. Texas didn’t really start building apartments until the early sixties. That first generation of complexes will reach the ripe old age of thirty by 1990, at which point the state could have apartment slums in all the major cities—and many of them in “good” sections of town.

The state’s new habitability law will help set minimum standards for rental housing, but tenants will have to sue to enforce the law, which very few tenants will do. And few attorneys will be out soliciting the cases, because there is not much money to be made on them. City housing codes also have a role in maintaining the quality of the housing stock, but if Dallas is any example, Texas cities are not seizing the initiative. Under the leadership of Mayor Bob Folsom, himself an apartment builder, the Dallas housing code has been weakened rather than strengthened. Three years ago the code was revised so that housing inspectors are now limited, for the most part, to inspecting the exterior of buildings. Since exteriors usually hold up better than interiors, many deteriorating apartment units will go unnoticed by already overburdened Dallas housing inspectors. A recent Dallas Morning News series concluded that Dallas has selective code enforcement that overreacts to conditions of low-income single-family dwellings but virtually ignores the state of large apartment complexes.

Addison’s city government has done considerably better, no doubt because the town is 98 per cent tenants. Councilman Jerry Easom, an apartment dweller and an old-timer (he’s lived in Addison for four years), was dismayed by the rapid property deterioration he had witnessed. Some of the apartment buildings were changing hands so frequently that clerks in the city tax office started joking about who owned what property that week. Easom drafted an ordinance that was unanimously passed by the tenant-heavy council, making Addison the first city in Texas to license landlords. The ordinance lays out the responsibilities of both landlord and tenant. Landlords, for example, must make their apartments comply with minimum health and safety standards, and they must respond to an emergency such as a broken water pipe within an hour or pay a fine of up to $200 a day. Easom said the ordinance is so new that there has not been time to evaluate its impact on the city, but he’s hopeful that it will halt Addison’s downhill slide into apartment slums.

Neither the state habitability law nor the Addison ordinance deals with who will pay for a property’s upkeep. “There are people who just can’t afford to live in property that is a hundred per cent perfect,” said Dick Covert, executive director of the Dallas Apartment Association. “The tenants’ groups say that it’s the owner’s obligation to fix a roof leak, but if the owner repairs the roof, he also has an obligation to raise the rent. Now, the question is, would a resident rather suffer with a bucket sitting on the living-room floor or would he rather pay higher rent?”

The tenant, of course, wants a decent place to live for a price he can afford. The traditional rule is that a family should allocate 25 per cent of its gross income to housing. George Stone says he finds a surprising number of Texans surrendering 35 to 65 per cent of their income to rent, and many of them don’t feel they are getting sufficient value for their money. Apartment owners respond that rental rates are not out of line with today’s inflated cost of living (in fact, between 1967 and 1978, the consumer price index rose 93 per cent while rents increased by only 63 per cent). For the first time since World War II, there is serious national debate about rent controls. Last spring, in the wake of property-tax reductions, the Los Angeles City Council passed a one-year, 7 per cent limit on rent increases. And residents of Santa Monica, who are 80 per cent tenants, approved an initiative rolling back rents to the May 1978 level. A Santa Monica rent-control board now has broad powers not only to set rents but also to approve the conversion to resident-owned property. Critics say rent control results in the deterioration of apartment stock because landlords can’t raise rents to keep up with maintenance costs. As one Californian puts it, “I’m not sure you can force a landlord to lose money.”

The other drawback to rent control is that it speeds the conversion of apartments into condominiums, which is especially hard on elderly people and other apartment dwellers on fixed incomes. (Santa Monica has nipped that trend in the bud by putting a moratorium on condominium conversion.) New York City has passed an ordinance requiring approval by 35 per cent of a building’s tenants before it can be converted. Other cities require that the owner give the resident tenants first crack at buying the apartment. Washington, D.C., is trying to conserve its low-income apartments by allowing conversion only in buildings where rent exceeds a certain level.

Condo conversion is beginning to catch on in Texas’ major cities. Dallas currently has about five thousand condo units. One of the biggest apartment converters in Texas is Daon Southwest, a giant California subsidiary of a Canadian corporation. The Dallas City Council encourages the conversions, maintaining that it allows residents who can’t afford or don’t want a single-family home to acquire some housing equity.

There have been some attempts in the inflation-battered cities of California to place punitive real estate transfer taxes on short-term speculators, but the efforts have bogged down in political and legal difficulties. Meanwhile, some tax reformers in Washington are talking about limiting or removing mortgage interest deductions and capital gains benefits from the tax codes. Such action might slow the rapid turnover of apartments, but it also would discourage new construction at a time when there is already a critical shortage of housing stock. Others in Washington argue that it is politically more feasible simply to give tenants a tax break on rent payments, thus allowing them tax parity with property owners.

One thing’s for sure, the economic war between landlords and tenants will continue as long as inflation rears its ugly head. With the price of homes increasing twice as fast as family income, the tenant class will continue to grow. On the flip side of that coin, the ownership of housing will become increasingly concentrated among the wealthiest 20 per cent of the population. What to do about these discouraging trends would make a timely subject for national debate during next year’s presidential campaign. Unless we reverse the current trends, we will become a nation of poorly housed tenants. And that’s nobody’s idea of the American dream.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Fort Worth

- Addison