Author: Smokestack Lightning: Adventures in the Heart of Barbecue Country

Author: Smokestack Lightning: Adventures in the Heart of Barbecue Country

Age: 52

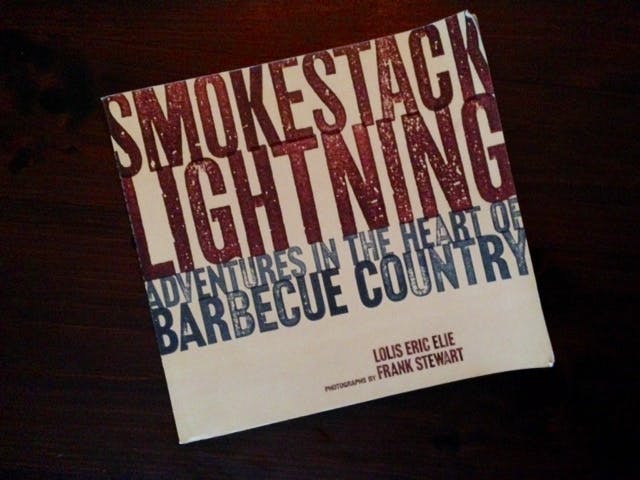

In the mid-nineties, Lolis Elie and photographer Frank Stewart travelled around the country eating barbecue for the book Smokestack Lightning. There aren’t many books as influential to my writing about barbecue than Smokestack. Sharing barbecue with Frank Stewart in Lockhart was a treat a couple years back, and last month I had the opportunity to do the same with Lolis Elie when I was in Los Angeles. We went a mini barbecue crawl through the city and talked at every stop about barbecue, Texas, and what it means to live and work in L.A.

Elie is a New Orleans native who traveled with Wynton Marsalis’s band as a jazz guitarist before settling back in New Orleans to write for the local Times Picayune. He moved to L.A. to write for the popular HBO series Treme, and continues to work in television writing.

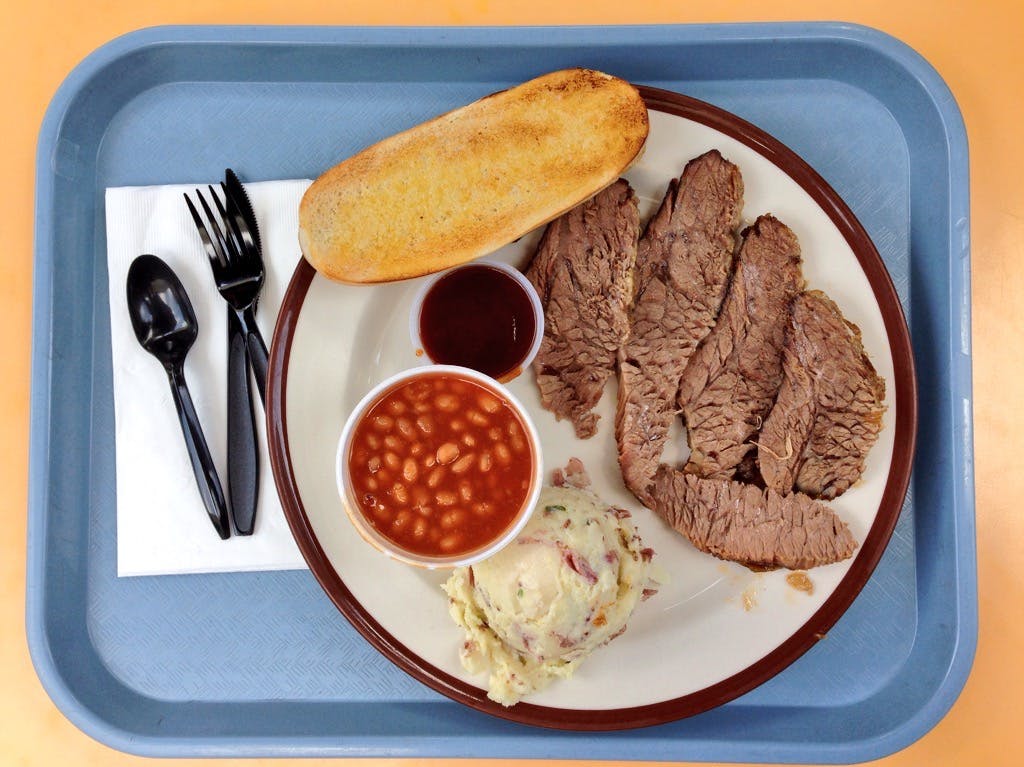

Out first meal was at Langer’s Deli which smokes some incredible pastrami, then it was Bludso’s Bar-&-Que in Hollywood. They do Texas style barbecue by way of Compton, where the original Bludso’s is located. Luckily, it was the best barbecue Lolis had eaten in L.A. As barbecue goes, the rest of the day didn’t match that high point. At least the conversation was always good.

Daniel Vaughn: When you set out to research Smokestack Lightning, how clear was your planned route, and how closely did you follow it?

Lolis Elie: It was a joke in a lot of ways. If you read the book closely, it’s obvious there are points where I’m learning as I go along. Other points it may seem like I know something. I knew something because I learned it from the last chapter. Memphis in May was a sample chapter. We knew about the event, and it made sense to start in May at the beginning of barbecue season. After that, I looked for events like the American Royal, and the idea was to find what was near this place. It wasn’t really well calculated, and Texas ruined everything that we planned. The place is so damn big, and there are so many places that you’re supposed to go to, we ended up spending three weeks in Texas. Before that, we had been spending about a week in a city and its environs, but you can’t do that in Texas because there are famous places all over, and different styles all over. I had no idea of the range of Texas barbecue. We also wanted to do some Midwestern stuff, and Frank is from Chicago, so that was a no-brainer. The whole idea was to find places where barbecue is an emblematic part of their identity.

DV: When you set out for Texas, you had in mind to visit the XIT Rodeo in Dalhart and Juneteenth in Mexia. What else was in your plans?

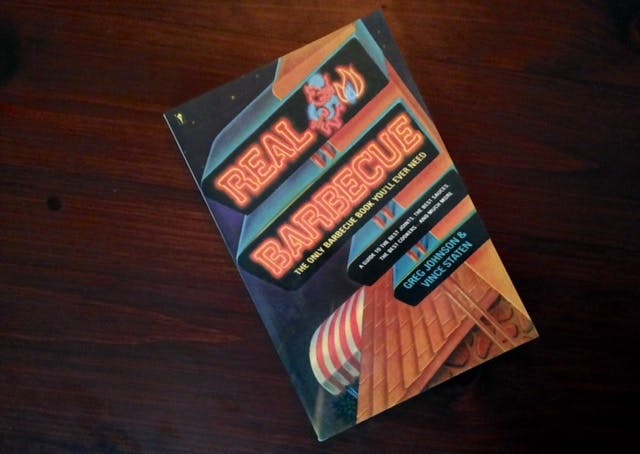

LE: Barbacoa for sure. Also, Vince Staten and Greg Johnson, their book Real Barbecue ended up being our main source of knowledge. They had a list of barbecue competitions in the back of the book, so I was looking through them for possibilities. I did go to a Texas competition. The guy running it said “To remember who we are, it’s I B C A. Who you be?” Then it was a matter of trying to hit the cities, but I found for the most part the barbecue in Texas cities was good, but it wasn’t very good. I’d love it if some of those places opened in my neighborhood, but I wouldn’t drive to Texas to them, except for Bob’s in San Antonio. We’d drive along the highways and just stop when we saw a place. The I got the idea of driving back from St. Louis to New Orleans, we’d take the back routes, the blue highways, and stop at all these places. What I found were a bunch of places that were justifiably unknown. Texas barbecue along those highways was edible. The story I read was that Joe Cotton kind of started that tradition. Then I remember Hinze’s had two places. One in Wharton and in Sealy, both of which I liked. Hinze’s did something interesting to me. They made their bread from scratch. It was basically like Wonder bread, so it was funny because you usually look down on that kind of bread, but they make it from scratch every day.

On the roots of barbecue

LE: If you go anywhere in the country, there’s a fair chance the barbecue place has some Western iconography in it, and Cowboy iconography specifically. I was wondering how this came about. One thing of course is that the cowboys had all these cattle they were driving up to the cattle market, and they would cook them along the way. But if you think about it, they couldn’t do that. They’re walking all day and stopping long enough to eat, sleep, and get ready to walk again tomorrow. There ain’t no barbecue time there. If you look at what they were really cooking, it was relatively quick cooking stuff. I also think Texas looms so large in this notion of the outdoor manly thing, it allowed the cattle drives to become part of barbecue lore. It began to make sense, but the people doing barbecue were the stationary folks, not those on the cattle drives.

DV: There also wasn’t a whole lot of fuel to be used for barbecue out on the range. There were more buffalo chips in those fires than oak trees for sure.

LE: I think Bob of Bob’s Smokehouse in San Antonio [now closed] gave me the most honest answer about whether or not mesquite makes the best barbecue. I asked him why mesquite was the best wood for barbecue, and he told me “Because that’s what I use.” This notion that there’s this one church of barbecue, and everyone else is a heretic. Well, I’ve never found that. Also, the kind of myth that barbecue was created by all these Czech butchers in Central Texas gets so well known that it goes unquestioned, not unlike the cowboy barbecue connection. It was always exciting to me to find ways in which these cherished myths made no sense. There was a point in Smokestack…we went to a place in Nashville. The guy was saying that Texas barbecue isn’t anything but a bunch of Tennesseans who went to Texas to show them how to cook barbecue. Of the people that died in the Alamo, at least half were from Tennessee, or at least that’s what he said. What I remember about that guy’s barbecue, it wasn’t very good, but it was very salty. I was at Cooper’s in Texas and thought, “Wow. This is very salty.” I would also add that, what I found is that sweet tomato sauces tend to be urban, and vinegar sauces tend to be rural.

DV: When you came to Texas, did you have some preconceived notions about what you’d find there, and did it hold up?

LE: I assumed it would be all beef and no pork there. Even at that point in the mid-nineties, we were moving toward a kind of national sense about what a barbecue restaurant should be. I went to several places, and a place called Burrer’s in Fredericksburg was a small place, and all they served was brisket [and sausage according to Smokestack Lightning, but no pork]. But if you went to any decent sized place, you’d find beef and pork, so that kind of destroyed that notion. Something that struck me about Texas was there was a lot less bad barbecue in Texas than anywhere else. In some other states we had damning with faint praise, but in Texas, not at all. So many places you go to that are famous for barbecue, half of them aren’t very good, and in Texas, I think good was the standard and the challenge was to find the very good.

DV: That’s the way I feel about Memphis and Kansas City. They have a few great places, but their bench just isn’t that deep.

LE: I’d agree. I wonder why that is because one theory in music is that you need to have ten mediocre trumpet players to produce one Clifford Brown or Miles Davis. In barbecue, it’s the same thing where you have to everybody trying it before that best one really comes out. But that wouldn’t make sense in Memphis or Kansas City where there are a lot of people doing it.

DV: The other side of that is, those great places need the mediocre places in order to be considered great.

LE: I can imagine walking into my place and saying “Look, you don’t want to taste as bad as that place across town, so you better up your game and do it right.”

DV: Have you been back to Texas to eat barbecue since traveling for the book?

LE: I went to Smoke in Dallas, which I thought was brilliant in the sense that it didn’t look at barbecue as just a meal, but as a way of preparing the meat and therefore pairing it in different ways. I think that was something that needed to be done, and could be done a dozen more ways that would still be interesting and compelling. I made it to the Holy Grail in Austin, Franklin Barbecue, and it was fabulous. I also loved La Barbecue. I also went to Hoover’s. He cooked for Toni Tipton Martin’s Soul Summit. We went to the restaurant too. It’s not primarily barbecue, but the barbecue was good. I dream about once a year of driving from L.A. to New Orleans and stop at all the places along the way, but West Texas is about as close to hell as one can get in terms of the drive.

DV: You can at least stop at Pody’s BBQ in Pecos.

LE: One of the habits of this business is seeing all of these roadside places and gas stations and seeing potential, but if you stop at every goddamned gas station that serves barbecue, you’ll be lucky to survive.

DV: Did you ever think when you set out on that road trip in the nineties, that you would be considered a barbecue authority in 2015?

LE: The funny thing is, the possibility of becoming a barbecue authority back then didn’t really exist. There were all these competitions, but they didn’t get mainstream until after that. I was also trying the thread the needle between a book about barbecue/food and a book about American culture. I was really trying to say something about culture, but that aspect of it hasn’t lasted. I also understood that the book was meant to be entertaining. I could give you a report about every place I went to, but that would be pretty boring. You might make it to Chicago, but you’re probably not going to get to ten places. But if I convince you to hang out with me, then I can make all these points about food or other social observations. What taught me about what the book would be about was going to Memphis and driving around the city and rural Tennessee. We listened to everything from Robert Johnson to Charlie Patton to Howlin’ Wolf and B.B. King. I tried to figure out how to do those metaphors. The strict metaphors may not have worked, but it was about trying to figure out how barbecue fits into this place.

DV: Looking back, the idea of a barbecue road trip back then wasn’t all that common. Did it seem that crazy of a thing to do then?

LE: The decision to write that book came when Frank and I were on the road with Wynton Marsalis. The idea of being on the road for any purpose may have seemed novel to most writers and photographers, we were just trying to figure out how to do a road book. The other thing is that I did hope we were doing something revolutionary and interesting. The critics who read it liked it, but not a whole lot of folks bought it. There’s a book I read in preparation called Blue Highways by William Least Heat-Moon that had been a best seller. I some ways I was trying to tread that ground. The sense of a story of America told in this unique way. So it was sort of disappointing that the book didn’t get viewed in that way. My initial training came as a jazz musician, so the idea of thinking you’re doing something great and having no one be impressed, I was prepared for that.

DV: What do you play?

LE: Guitar, but I was not in danger of being a great musician, but it taught me a lot.

DV: As a musician on the road, did you chose barbecue instead of some of the other vices musicians are known for?

LE: This was a different generation of jazz musicians. We didn’t have heroin users on that tour. But I have a very specific story. We were in North Carolina at a place called Beale’s, and they brought us barbecue from this local place that was very famous, but I don’t remember the details. Before we get to questions of quality, this was just very different from our perception of barbecue. Because it was whole hog, the ribs looked terrible, but the fact that it was so important to these people and they were so proud of it…you couldn’t judge it by our standards. Or, as I learned later, we were incompetent to judge this by any standard, because all you can say is that it doesn’t taste like mama’s.

DV: You’re from Louisiana, so is there a Louisiana barbecue?

LE: No. Mind you, the story of Louisiana, particularly in the context of music, is you have the Creoles who have their own thing going on. Then you have the Louisiana Purchase and all the Americans who came in. Among them were African Americans. If you look at Louisiana as being a mix of the Creole and the American, my theory is that the seafood or the African based dishes like gumbo and jambalaya came to be emblematic. The water also became so much of the culture. The right of passage of going out on fishing trips with your father or trips to the bayou. Growing up we always had barbecue, and I remember it being good. It was even good when I was old enough to discern. But there are two questions to consider. Is there barbecue in Louisiana, and the other is whether it is stylistically distinct. The Cajuns have their boucherie, or hog killing. I think anyone doing a hog killing is doing a mix of quick grilling and stews, and then hams that they would put up to smoke. I don’t know if there’s anything distinct enough to be called a barbecue tradition coming out of that.

DV: Have you found any great barbecue out here?

LE: You introduced me to Adam Perry Lang, and after that it’s hard to go back to other barbecue. I’ve been to a few places here, all of which are good, but none great. There’s one I have high hopes for from a French Laundry alumni called Barrel & Ashes. I’ve been to Bludso’s. We did a barbecue safari, and tried Horse Thief in downtown, which I like. We went to Big Mista’s and a few others.

DV: But you didn’t find a go-to place?

LE: When I was doing the barbecue book, we went to all these places that were good, but how do you actually evaluate a place? I couldn’t say many were bad, so I started thinking about it in terms of how badly do I want to go back, and the truth is, none of these places have made me want it again.

DV: Do you cook your own barbecue?

LE: Not anymore. One is moving out here. Two is losing my pit in Katrina.

DV: Do you have room for a pit in L.A.?

LE: Actually, I could do it. The place I rent is a house, so there’s room for pit. The landlord has an electric grill which I’ve used once. Given my religion, an electric grill is kinda difficult.

DV: You mentioned that you’ve also found it challenging to find real community here in L.A., but I bet if you cooked barbecue, you could build a community in your backyard pretty quickly.

LE: I’ve had several dinner parties cooking New Orleans food, and it’s the kind of thing where you invite folks over and have a great time, but I never hear from them again. That’s some California stuff that’s unlikely to happen in New Orleans.

DV: Are you sure it wasn’t because the of the food?

LE: [Laughing] They cleaned their plates and said they loved it, but then everyone here is an actor. There’s a great B.B. King line “Nobody loves me but my mother, and she could be jivin’ too.”

- More About:

- Black BBQ