Researchers at Texas A&M are seeking to improve Texas barbecue. This isn’t the first time that an institution of higher learning has aspired to this lofty ambition; Harvard students already tried to design the ultimate smoker. And now the Aggies are focusing on the meat of the matter, so to speak.

Earlier this week A&M’s Rosenthal Meat & Technology Center hosted a barbecue “town hall,” and among the many topics discussed, Dr. Jeff Savell mentioned a new study they were about to embark on related to barbecue. Curious, I asked for more details, and Dr. Davey Griffin introduced me to McKensie Harris, the graduate student charged with shepherding an experiment called “Effects of Aging on Brisket Palatability,” a.k.a the Brisket Aging Project. I suggested “The McKensie Project” as a title to make it sound more official.

It’s long been debated that the length of time a brisket stays in its cryovac bag—a process known as wet-aging—before it hits the smoker may have an effect on the brisket’s flavor and tenderness. This experiment will test that theory. You may have heard of expensive dry-aged steaks that spend months inside humidity controlled chambers in order to develop richer flavors, but the process of wet-aging is simpler. It’s accomplished by leaving cuts of beef in the plastic packaging they come in from the slaughtering plant. Think of it as the lazy-man’s dry-aging. You could forget a box of briskets in the cooler and instead of them being past-date, you could market them as wet-aged.

Through a grant from the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (funded from the Beef Checkoff Program) researchers at A&M will be aging and tasting a series of smoked briskets that have spent anywhere from seven to 35 days aging. They’ll be pitted against one another in a blind taste test by a panel of judges. The scales and language for the tasting panels is still in development, but they’ll be asked about tenderness, flavor, juiciness, and overall impression of the briskets.

In order to minimize effects from certain variables—i.e. breed or other genetic differences—briskets from the same animal will be aged differently and tasted against one another. Steers will be hand-selected by the team in January. Once the briskets have been harvested, they’ll both age for seven days, then one will go to the deep freeze to stop the aging process. The other side will continue for a total of twenty-one or thirty-five days. Both briskets will spend at least a week in the deep-freeze before the smokers are fired up.

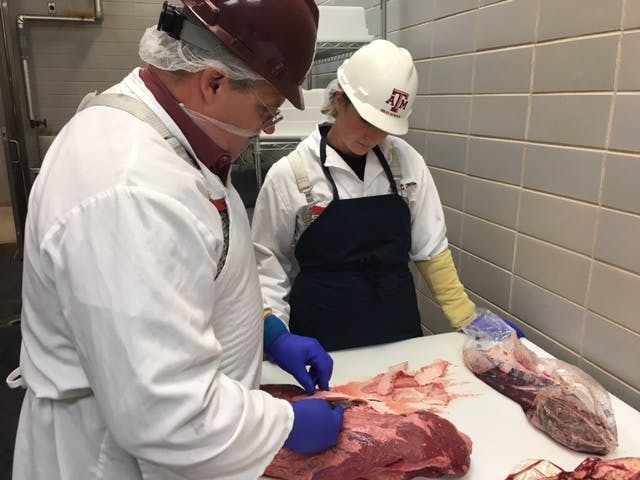

“This is my first experience with brisket,” Harris, a native of Wyoming, told me as she gouged the fat cap of a practice brisket. Dr. Savell—who worked on writing the grant proposal with Meat Center manager, Ray Riley, and Dr. Griffin—called Harris over the summer to see if the project interested her, and it did. I asked if any Texas-bred students were unhappy that she was assigned to the cool barbecue project. She said no, and that some of her fellow students even suggested they’re tired of barbecue. When she asked “How do you get tired of barbecue?” I knew they had chosen wisely.

For now the experiment focuses only on Choice grade beef. I asked if researchers would taste Select briskets against Prime ones to see how much the lower quality meat might improve through aging. “We’d love to do that, but every time you add a grade, the cost of the study doubles and we don’t have that kind of budget,” Dr. Griffin told me. If the outcomes here show added value through aging, then new parameters like beef grade and storage temperature may be considered for future studies.

As for the barbecue tasting, the salt-and-pepper briskets will be smoked in March for the panelists, and the results tallied soon after. It might be a while before we all know the outcome. As Dr. Savell noted, “it takes about a year to get anything published” in an academic journal.

These briskets are in good hands. The Aggies are certainly not new to protein experimentation and barbecue is also a forté—Dr. Savell and Riley teach ANSC 117, Texas Barbecue every fall for 25 lucky students. Savell sounded particularly excited about the outcome of the experiment, and its value for Texas’s favorite cuisine. “It would be nice, regardless of what we find, that this opens the door to more researchable areas in the Texas barbecue arena.” Folks, this is why God created Texas A&M.

- More About:

- Brisket