A few months ago I was at Smolik’s Smokehouse in Mathis to buy some smoked meats, including a link of their homemade Czech-style sausage. As I waited for my change, I asked the clerk what made this particular link of sausage a Czech sausage. “A Czech made it” was her simple reply without a hint of sarcasm. This spartan response piqued my curiosity and launched me into a search from Hallettsville to West for an actual definition of what constitutes Czech-Tex sausage—to, if you’ll humor me, find out how the sausage is made. We see them on menus all over Central Texas, but what can you expect when you bite into one?

The Czech who made that Smolik’s sausage was Mike Smolik, a third-generation barbecue man who uses a family sausage recipe and smokes it over hickory. Like most proprietors that I spoke with, Smolik wasn’t giving up his secrets, but he would offer that he uses pork and beef and seasons it with salt, pepper, garlic, and paprika, among other ingredients. (During my quest, I found that a variation on this combination was pretty standard.) The recipe originally came from his grandfather William Smolik, and probably even precedes him. Mike’s elders used garlic powder in their mix, but he insists on roasted garlic for the flavor. That wasn’t the only improvement. “I didn’t realize how much I changed the recipes until I started looking back at how simple the originals were.”

Not everyone is so cavalier with their family’s recipe. Gary Vincek at Vincek’s Smokehouse in East Bernard wouldn’t dare mess with what he believes to be a 200-year-old family recipe from Moravia. His doesn’t use paprika, or at least he wouldn’t divulge that part of the recipe, but the rest is the familiar mix of beef, pork, salt, black pepper, and garlic. In fact there wasn’t a sausage I could find that was called “Czech Style” that didn’t include these five ingredients. I asked Vincek what he considered a Czech sausage (aside from having a Czech preparing the dish). “I guess it’s the coarser ground meat,” he told me. He uses grinding plates rather than a buffalo chopper to attain this desired texture.

Over time many of these family recipes that were developed for fresh or smoked sausages have taken on some significant variations: flavor enhancers and additional preservatives for extending shelf life are two common additions. Consider Slovacek’s in Snook, Texas, which is now the largest producer of Czech sausage in the state. It started as a small operation by John Slovacek in 1957. Today it’s run by Tim Rabroker, and they make over four million pounds of sausage for grocery store shelves across the state. You won’t find one labeled as Czech-style, but their popular pork and beef sausage follows the pattern. The original Slovacek recipe was actually what they sell as hickory smoked sausage. I asked Rabroker (who refers to himself as a “square-headed German”) his definition of a Czech sausage: “It has to have garlic and coarser grind.” Simple enough.

Slovacek’s has added sugar, red pepper, and MSG for a flavor boost and sodium nitrite for preservation. The fact that they have to attach a label of ingredients on the package is obviously a big help in determining the recipe, but it doesn’t give the full picture. Those preservatives are common ingredients in commercial sausages, but for obvious reasons you won’t find them in the fresh sausage recipes of old Czech cookbooks.

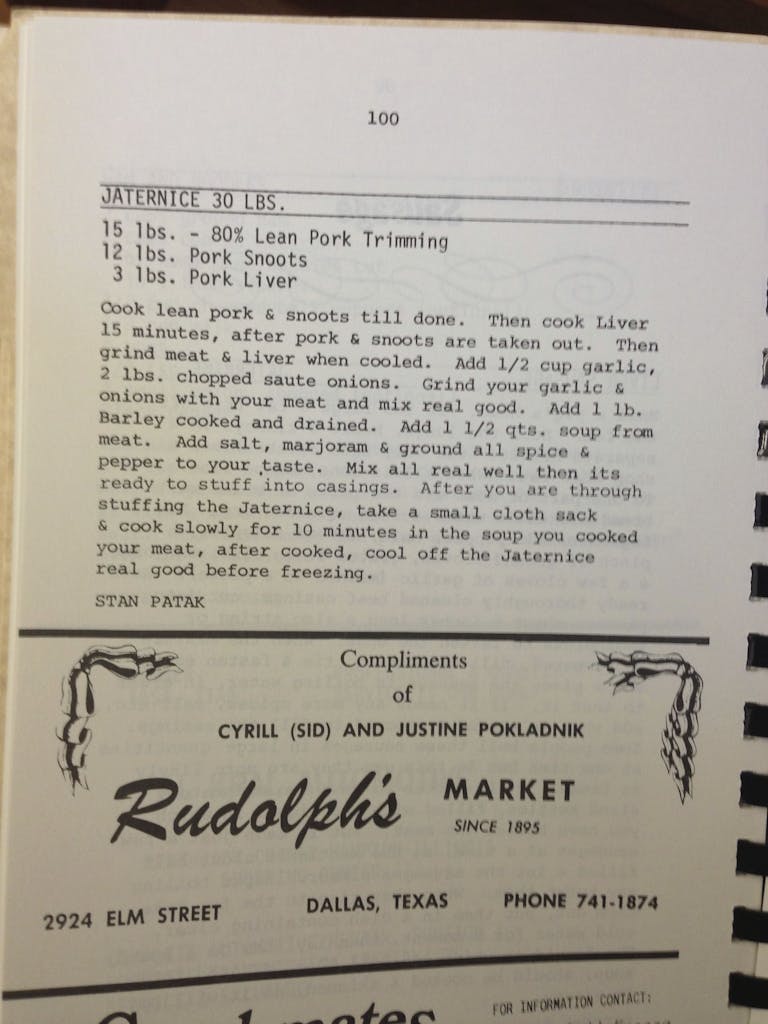

The Texas Czech Heritage and Cultural Center in La Grange is part museum, part library, and with its impressive collection of Czech cookbooks, the center proved to be a great resource in my research. I leafed through all the cookbooks I could find trying to find sausage or klobasa recipes to see if I could find the link between what we consider Czech-style sausage in Texas and how it was made across the Atlantic. What I found was a persistent propensity for pork. Out of dozens of recipes there was only one sausage that had any beef in it. In fact, there were far fewer klobasa recipes than I had expected, but every book had at least one option for jaternice (pronounced yee-ter-neat-za). Jaternice is a sausage made with pork offal along with rice or barley, and is reminiscent of Cajun boudin. The similarities make sense given that jaternice and boudin are both traditionally made during a celebration where a hog is killed and every part is used for one specialty or another. In Louisiana they called it a boucherie and in the Czech Republic it’s called a zabijacka, but the result is the same—lots of pork offal and some starchy filler stuffed into intestines.

But though jaternice (sometimes called jitrnice) recipes were bountiful in these old cookbooks, it was a rarity to find it in Central Texas. To further distinguish the new ways from the old-world ways, nearly every Czech sausage I encountered had beef in it. That includes the one version of jitrnice I found at Maeker’s in Shiner. In addition to pork head, tongue, kidneys, and liver it also had beef hearts and kidneys. Of course there was some salt, pepper, and garlic, but it could have used a bit more. The overwhelming liver flavor made it hard to get down for me. Maeker’s pork-and-beef sausage was a vast improvement.

Shiner is also home to Patek’s. It might not be a familiar name, but if you’ve seen the Shiner Smokehouse label show up in your grocery store recently, it’s made right here at Patek’s. Brian Patek is the fourth generation of this Czech family and the current proprietor of the operation Joseph Patek opened in 1937. Their recipe is the only one I found without black pepper. That led me to ask the women working the counter if that still made it a Czech sausage. Referring to the mixed German and Czech heritage of Shiner, one of the women said “I guess it belongs to whichever nationality wants to claim it.”

That was the same attitude at the very German Prause Meat Market in La Grange, a town which also has deep connections to both German and Czech immigrants. I asked Gary Prause if he made different styles of sausage for each nationality. He smiled and said “we just give them what they want.” If the customers ask for German sausage he pulls from the same tray of links as when they ask for Czech sausage.

The Czech-owned City Market in Schulenburg run by the Smrkovsky family feels about the same way. There are a half dozen sausages for sale in their case. They don’t call their beef-and-pork option a Czech-style sausage, but it follows the pattern. A man working the counter was again non-committal when it came to labeling the sausage with a specific qualifier, but he did note that it wasn’t a Bohemian sausage. He figured it would have to have sage in it to be Bohemain. That comment led me to go back and ask Gary Vincek about the addition of sage in his sausage. He cut me off. “I don’t have sage in my store…I don’t like it.” Then again, his family is Moravian.

To clarify, when using the term Czech here, I’m referring to Texas immigrants who identified themselves as such. At the peak of Czech immigration in Texas they were coming primarily from Bohemia and Moravia which are within the present day Czech Republic. By 1918 when Czechoslovakia was formed (bringing in Slovakia and a portion of the Ukraine and Silesia) Czech immigration into Texas had just started its decline. From the Handbook of Texas:

By 1900 the number of foreign-born Czechs in the state had climbed to 9,204, and by 1910 to 15,074. After this time, however, Czech immigration decreased; foreign-born Czechs numbered 14,781 in 1920, 14,093 in 1930, and 7,700 in 1940.

I thought I’d ask some current residents of the Czech Republic if the sausages available in the meat markets and grocery stores of their country resemble the recipes we have here in Texas. I asked Tereza Jahnova who works for Bohemia snack company in Prague what a sausage counter might look like in the modern day Czech Republic. Was there one type of sausage more popular than others, a sort of signature regional sausage? The short answer is no. “Each meat market might have their own recipe for their own signature klobasa, but they will never have only one type of klobasa. They will have a wide variety, of which some might even be from Germany or Poland.” She said that paprika and marjoram are popular spices with garlic being predominant. Whether they call it klobasy, klobase, klobasa, kolbasa or klobás, they just mean sausage. These terms don’t take on a specific meaning until they’re used overseas in places like Texas. Here the word klobasa on a label signifies the recipe’s heritage.

A sign in the window at Charlie’s Grocery & Market (and gas station) in Ennis advertised “CZECH KLOBASE. Authentic Manak Recipe Available Here.” I went inside to ask if they had any hot and ready to eat. The clerk pointed to a heated tray of sausage on rollers a la 7-11 style. As I paid for it I inquired about the myriad sausages in the case. They had Polish Kielbasa from Rudolph’s Meat Market in Dallas (which, it turns out, was the hot sausage I was holding that was supposed to pass off as Czech) along with K&K’s Czech sausage and a version from Holy Smoked Sausage Company in Waco. I bought a package of each, a cooler and some ice, but I wasn’t any closer to knowing what Manak style sausage was. At least I had some juicy links from Holy Smoked to munch on while I did some research.

A few weeks later back in Dallas I met first-generation Moravian Jerry Manak in his dining room just a few blocks from my house. It turns out he owns K&K Sausage Company in Dallas, so I already had some of his product in my refrigerator. That “authentic Manak recipe” was one he developed from memories of Czech sausages he’d eaten all his life. I noted the caraway seed on the label, which seemed like an outlier based on all the others I’d eaten. “It has to have it. Everything I had in my life, everybody put caraway in it.” And it worked. It wasn’t too heavy, and when dipped into some good mustard, these links were great. An improvement over their Dallas-based competition, Rudolph’s Market, which produces the only other Czech sausage with caraway I could find. Its flavor was flat, and the once chubby links looked deflated after losing too much fat during the cooking process. I much prefer their juicy Polish kielbasa.

If caraway sounds like an oddity, you have to remember the variation of sausage recipes in the Czech Republic. Gabe Bunch, a reader of tmbbq.com, looked into finding a sausage recipe from some of his associates in Prague. The recipe they chose to be representative of a traditional Czech sausage included beef and pork, but the garlic had been replaced by nutmeg. A Texan would hardly recognize that as klobasa.

Robert Marianski, a sausage scholar who writes for the site Meats & Sausages argued that the sausage most common in the Czech Republic is utopence. According to Robert, they are “served everywhere. In bars, homes and restaurants. The name means ‘drowned.’” Drowned because they are pickled sausages, much like a jar of Vienna sausages. Utopence is one of the few sausages whose origin is in the Czech Republic. Robert adds “[Czechs] produce many sausages which they borrow from other countries.”

Vencil Mares at Taylor Café doesn’t much care what the origin of his sausage recipe was when he calls it “bohunk sausage.” The term bohunk is a derogatory one that entered the English language about the time Czech and Hungarian immigrants flooding into Texas through the port of Galveston. In short, it means a Bohemian-Hungarian-Redneck, but Vencil, who is of Bohemian decent, feels he can use the term as he likes. He calls his sausage that because of his roots, but the base for that recipe came from his time working at Southside Market in Elgin. He tweaked it to his tastes, but there wasn’t a Mares family sausage recipe passed down to him.

Just next door to Vencil’s place in Taylor was a small storefront that Rudy Mikeska first used in 1952 to sell his sausage. He later moved to Second Street just across the parking lot from Louie Mueller Barbecue. This is the barbecue joint that Tim Mikeska ran for a years before closing it to focus more on the family sausage business. He sells so much Czech sausage in the Windy City that he calls himself the sausage king of Chicago, a real-life Abe Froman (shout-out to the Ferris fans out there). The well-respected Smoque BBQ on Pulaski Avenue sells his sausage right next to their excellent smoked brisket. Tim Mikeska is a bit of a family historian, so he has better notes on his family’s old sausage recipes than most.

[The recipe] would have originated from Zadverice, Moravia and would have come with my great grandfather to Texas around 1880. The notes show both 100 percent pork and eighty-percent-to-twenty-percent pork to beef ratio. The common spices to all these recipes is salt, black or white pepper, paprika and garlic. Other ones also list mustard powder, onion powder, “pinch” of caraway. In going through my emails with old country cousins, Bohemia influenced more garlic, allspice, and marjoram.

The recipe that Tim Mikeska sells today is more focused. Beef, pork, salt, black pepper, and garlic are joined only by cayenne. This is the same sausage that Rudy was selling out of that tiny storefront in 1952. Coincidentally, he took over that lease from J. J. Novosad who had just moved his meat market operation further south to Hallettsville, and he took his father’s sausage recipe with him. J. J.’s grandson Nathan Novosad now operates Novosad’s BBQ and still uses the same recipe which has a more black pepper than most and an extra kick from red pepper. There’s also an herby flavor from what I thought was sage, but after looking back it might have been the more traditional marjoram. Nathan isn’t telling either way. Nathan, his mother, and a safe deposit box are the only one with the full recipe, and for good reason. It’s the best sausage I can remember eating during my Czech sausage search.

If you’ve been to Novosad’s and ordered the hot sausage, then you probably didn’t eat the sausage I’m writing about. What you get along with the barbecue is a hot link that is primarily beef. To get the really good stuff you need to ask for the smoked pork-and-beef sausage from the meat case. It’s got a little more pork and a little less fat. You’ll have to take it home to warm it unless you call ahead, but it’s worth the wait.

Just down the street in Hallettsville, a large painted sign reads “If it ain’t Janak’s it ain’t Sausage” Inside it looks more like a boutique store than a sausage factory. You can get jellies, candies, and a whole line of smoked sausages. Included is a “Czech Style” sausage that has all the standard ingredients including some paprika. It’s not as good as Novosad’s, but still worth traveling for.

Way up north from Hallettsville is the Czech town of West. For over a century, Nemecek Brothers Meat Market sold Czech hams and sausages. It closed a few years back and still sits vacant. Now you have to go to Nors Sausage & Burger House in downtown West where Matt Nors now carries on a tradition of Czech sausage-making in West, Matt’s grandfather Emil Nors even worked at Nemecek’s for a time. A short-lived meat market that Nors opened next to the Old Czech Bakery on Oak Street closed late last year, but you can still find the Nors family recipe at the restaurant. It became an informal meeting place for rescue workers in the aftermath of the April 2013 explosion in town. Locals and out-of-towners alike got their fill of smoked links with a solid punch of garlic, which are some of the best I’ve had in Texas.

A more popular stop in town is the Czech Stop on the I-35 service road. I was excited to find their own private label sausage amidst all the kolaches. At the register I asked where it was made. I was a bit disappointed that they just slapped a sticker on the pork-and-beef sausage from City Market in Schulenburg, but at least the Czech Stop is more committal on its provenance calling it “kolbasa” on the label. One market’s pork-and-beef sausage is another store’s Czech sausage.

So, what is a proper Czech sausage in Texas? No single definition will satisfy everyone. Some will argue that there’s the a single defining element, like caraway, but in the end everyone has different taste. It seems to me that the basic description would be a coarsely ground beef-and-pork sausage with salt, black pepper, and garlic for seasoning. That’s a Czech sausage, in Texas anyway, especially if a Czech makes it. As the Czechs say “každý má jinou chuť.”

Highly Recommended:

Mikeska Brand – Taylor

Nors Sausage & Burger House – West

Novosad’s – Hallettsville

Smolik’s Smokehouse – Mathis

Vincek’s Smokehouse – East Bernard

Recommended:

City Market – Schulenberg

Holy Smoked Sausage – Waco (from Charlie’s Grocery & Market in Ennis)

Janak’s – Hallettsville

K&K Meat Co. – Dallas (from Charlie’s Grocery & Market in Ennis)

Patek’s (Shiner Smokehouse) – Shiner

Slovacek’s – Snook