This article originally appeared in the September 2017 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Why the ’Boys Are Back.”

It was the fourth quarter of Dak Prescott and Ezekiel Elliott’s first NFL playoff game. They were on their home field in mid-January, and their team was displaying uncommon resilience against Aaron Rodgers and the Green Bay Packers. The ’Boys had fallen behind 21–3 in the second quarter, and the fans at AT&T Stadium in Arlington, instead of descending into all too familiar fits of despair, simply waited for the team to prove to the national audience what had begun to dawn on them early in the pre-season: this team was something special.

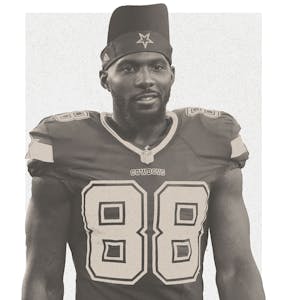

The Cowboys responded. Down by eight points in the fourth, the defense executed a perfect blitz against the elusive Rodgers, with journeyman safety Barry Church dragging one of the game’s best quarterbacks to the ground. Back on offense, the Cowboys’ rookie quarterback, Prescott, played with the poise of a veteran, leading an eleven-play, 80-yard march downfield. Elliott, the rookie running back who led the league in yards last year, brought the ball inside the 10 by pulling a spin move that left massive Green Bay linebacker Clay Matthews wrapping his arms around a cloud of dust. To cap it off, Prescott hit Dez Bryant for the receiver’s second touchdown of the game. The quarterback rushed up the middle on the two-point try to tie a game the Cowboys had trailed by eighteen points some thirty minutes earlier.

The fairy tale ending, alas, was not meant to be. The Packers reclaimed a three-point lead. The Cowboys ripped off a six-play drive in 58 seconds and tied the game again. But then, with 35 seconds on the clock, Rodgers drove into field-goal range by hitting his tight end with 3 seconds to play to set up a game-winning kick for the Packers.

The Cowboys have been no stranger to heartbreak in recent years, but as heartbreaking playoff losses go, this was perhaps the most encouraging one in NFL history. “That’s one of those losses where you go into the off-season and you can’t wait for the next season to begin,” says Bob Sturm, a host of the Bob and Dan radio show on KTCK, in Dallas. “It put the rest of the league on notice.” Here was the Cowboys team of the future: a team whose key components were all under contract through the end of the decade, a team that, it was easy to believe, would only get better and better.

If you time-traveled back to 2001 (when this magazine ran a cover story that asked, “Is Jerry Jones the Devil?”) and told a lifelong fan that the Dallas Cowboys might be the best-run organization in the NFL, it would sound about as unlikely as the words “Academy Award winner Matthew McConaughey” or “President Donald Trump.” And yet, the Cowboys, who haven’t exactly earned the title “America’s Team” in more than a decade, are suddenly looking the part again.

Or maybe not so suddenly. A closer look reveals a few key turning points that led the Cowboys to become not just one of the NFL’s most promising teams but among its most solidly constructed. Even more surprising: perhaps the most important engineer of those moments goes by the last name Jones—but it’s not recent Hall of Fame inductee Jerry.

May 8, 2014: Drafting Zack Martin Over Johnny Manziel

On May 8, 2014, the Dallas Cowboys held the sixteenth pick in the NFL draft. After months of speculation about what would happen with Johnny Manziel, the most intriguing prospect of the draft class, the boom-or-bust quarterback was still on the board. Quarterback-hungry teams like the Houston Texans, the Tennessee Titans, the Minnesota Vikings, and the Oakland Raiders had all snatched up future Pro Bowlers at other positions, leaving the Texas A&M superstar waiting as he watched his opportunities dwindle in the first round.

And then it was the Cowboys’ turn to pick. Jerry Jones had, in the buildup to the draft, flirted with the idea of drafting Manziel to be the team’s quarterback of the future behind Tony Romo. It would have been a classic Jerry pick: a splashy, headline-grabbing star with Texas ties and the potential to be a ratings-dominating superstar for the next decade plus—but also the sort of high-risk/high-reward prospect that was the definition of a luxury pick for a team with a quarterback as talented as Romo under center.

Jerry wanted Manziel. The rest of the Cowboys front office did not. So Jerry’s son, executive vice president Stephen Jones, who in recent years had stepped into the sort of general management role that Jerry had never trusted to one of his hires, had made his dad a deal. The team’s defense wasn’t a cohesive unit, and there were sure-thing defensive prospects like linebackers Ryan Shazier and Anthony Barr and defensive tackle Aaron Donald in the draft class. Jerry agreed that if one of those players was still available when the Cowboys were on the clock, they’d leave Johnny Football still waiting—and then Stephen pushed even further. He wanted Zack Martin, a guard from Notre Dame, before Manziel too.

Sure enough, the defensive players the Joneses coveted were gone by the time they picked. It came down to Manziel or Martin: the flashiest player in years, at the game’s flashiest position, or a dependable interior offensive lineman who, if he excelled on the field, would rarely have his name spoken aloud by announcers, who’d be marveling at what ball carriers did in the holes he’d create.

Jerry looked around the Cowboys’ draft room, hoping to find someone who would support the idea of taking Manziel—and did not find anyone. On television, the broadcasters speculated as to what was happening behind the scenes. Manziel Mania author Jim Dent reported that Jerry had had the A&M passer’s draft card in his hand when Stephen told him that Martin was the consensus choice.

“Son, I hope you’re happy,” the elder Jones had said, according to Sports Illustrated. “But let me tell you something: you don’t get to own the Cowboys, you don’t get to do special things in life, by making major decisions going right down the middle. And that was right down the middle.”

It may have been. But it was also a move that would help the Cowboys find an identity that wasn’t tied to having one marquee name and winning the hype cycle during the off-season. Instead, the team’s identity was built in the trenches. Martin, who’s now entering his fourth year, is a three-time Pro Bowler and two-time All-Pro, the anchor of the most feared—if, paradoxically, anonymous—of any position group on any team in the league. Manziel, of course, is almost certainly out of the NFL for good.

Behind Martin—as well as tackle Tyron Smith and center Travis Frederick, two other first-round picks on the offensive line—Cowboys rushers who might have been ordinary elsewhere have turned into stars. Rushers who might have been stars on other teams, meanwhile, could become legends.

March 12, 2015: Letting DeMarco Murray Walk

Rushing behind Martin and the rest of the Cowboys offensive line in 2014, DeMarco Murray etched his name into Cowboys lore. Murray, a third-round draft pick in 2011, had spent his first three seasons struggling with injuries, but with the revamped Cowboys line doing his blocking, he started shattering NFL records in 2014. He rushed for more than 100 yards in each of the first eight games of the season and broke a record that the great Jim Brown had held since 1958. He scored thirteen touchdowns and rushed for more than 1,800 yards through the course of the season, more than Emmitt Smith, Tony Dorsett, or Herschel Walker ever did.

With Murray in the backfield, the Cowboys’ star began rising in the NFL. Since the 1999 season, the Cowboys had posted a win-loss record of 120-120 and won only two playoff games, but a promising roster was finally taking shape. Cowboys fans thrilled at the thought of Murray playing the Emmitt Smith role in an offense built around the “triplets” strategy of the mid-nineties glory days, with Dez Bryant as the Michael Irvin–like wideout and Tony Romo playing Troy Aikman.

But Murray was approaching free agency. The pressure on the Cowboys’ front office to keep him was immense. Fans loved him. He was a big character in the locker room, who ate breakfast every morning with the team’s running backs coach, the two poring over various defensive fronts. NFL columnists published stories with headlines like “Dallas Cowboys must re-sign DeMarco Murray on multi-year deal.”

The Cowboys resisted the pressure, confident that with their offensive line doing the blocking, Murray wasn’t irreplaceable. Murray tested free agency and ended up inking a five-year, $42 million deal with the arch-rival Philadelphia Eagles. Fans were apoplectic. Michael Irvin, who’s never been known to be a harsh critic of the Jones family, told Dallas sports talk radio station 105.3 that the move was “poor decision-making on the Cowboys’ part, on many different levels”—affecting everything from the team’s performance in the backfield to the chemistry in the locker room.

Stephen, for his part, explained the team’s decision-making process to the Associated Press. Rather than returning to the triplets philosophy, he said, “We have to develop [and] structure a football team with the salary cap. You can’t pay a top receiver, a top quarterback, a top pass rusher, a top left tackle. You’ve got to make hard decisions.”

Instead of paying Murray top dollar, the Cowboys signed Darren McFadden, a 2008 draft bust out of the University of Arkansas, alma mater for both Jerry and Stephen Jones. Rushing behind Martin and the offensive line, McFadden posted a solid 1,000-yard season. And then, of course, when the 2016 draft came, the team jumped at the opportunity to build from the ground up with a younger, healthier, more effective—and cheaper—back than Murray, signing Ezekiel Elliott to a four-year, $25 million deal, after taking him with the fourth pick overall.

Elliott’s impact was immediate. He rushed for over 1,600 yards and fifteen touchdowns and was selected as first-team All Pro (though he spent the off-season under investigation by the NFL). But it turns out that the most significant selection the Cowboys made in the 2016 draft wasn’t the prized running back. It was a fourth-round pick who would enter training camp on the bubble to make the team.

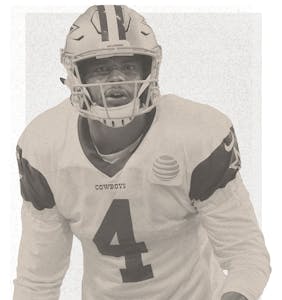

August 27, 2016: Discovering Dak Prescott

The third preseason game of 2016, against the Seattle Seahawks, was the one in which fans would get to see how much rust Romo had shaken off after playing in only four games the previous season. Starters usually make brief appearances in the first two preseason games, but game three is considered a dress rehearsal for the year to come. A minute and a half into the game, facing second and seven from the 39-yard line, Romo’s—and the Cowboys’—fortunes shifted forever. Scrambling against the blitz, Romo escaped the pocket and was tackled awkwardly from behind by defensive end Cliff Avril. He would attempt only four more passes in his NFL career.

Even before they lost Romo, the Cowboys had known that the 36-year-old veteran with a history of injuries wasn’t a sure bet, so they’d brought in seven quarterbacks for predraft visits. They weren’t planning on needing a starter (and they didn’t know that backup Kellen Moore would break his ankle). During the draft, the Joneses watched as the prospects slipped off the board one after another: Jared Goff and Carson Wentz before the Cowboys even made a selection; Paxton Lynch after the Denver Broncos outbid Dallas in a trade with the Seahawks in the first round; Christian Hackenberg, Jacoby Brissett, and Connor Cook before Dallas selected in the fourth round. That left the frustrated Cowboys taking defensive end Charles Tapper with the team’s first pick in the fourth round and then selecting a QB out of Mississippi State named Dak Prescott with the 135th pick at the end of that round. He was the first quarterback drafted by the Cowboys since 2009.

NFL talking heads praised the Prescott pick. He had the potential to develop into a starter, they said—if he sat behind Romo for a few seasons. NFL.com analyst Gil Brandt, who worked in the Cowboys’ front office from 1960 until Jones bought the team, in 1989, summed up the measured optimism on Twitter, comparing Prescott to a better Tim Tebow and noting, “He has [a] chance to eventually replace Romo.”

With Romo out, Moore out, and no experienced backup on the market, the team was Prescott’s. And what happened next was the sort of surprise that turns kids with a budding interest in the game into lifelong fans.

Prescott had some jitters to work out in the team’s season opener. He passed for 227 yards and no touchdowns in a 20–19 loss to the New York Giants. It would be the only loss Prescott would know in the next three months. He went on a tear through the NFL, quickly evolving into the sort of special player that every team that took a quarterback ahead of Prescott in the draft dreamed they’d end up with. He scored his first touchdown on the ground against Washington in week two, then threw for one and rushed one in against the Chicago Bears in week three. He didn’t throw an interception until week six, when the Packers picked him off in a game that also saw him throw three touchdowns on his way to a 30–16 triumph. He put up three touchdowns again in weeks eight, nine, and eleven.

Eventually Romo was healthy. Eventually it didn’t matter. The Cowboys had gotten lucky that a talented quarterback like Prescott had lasted until the fourth round of the draft, and when circumstances led the team to put its faith in an unproven, untested rookie, it found the new face of the franchise.

But it wasn’t all luck. Prescott, in fact, had been the quarterback the Cowboys had met with more times than any other before the draft. As a reward for looking beyond the obvious, the team ended up with a quarterback who could make stars out of sleeper receivers like Cole Beasley and Terrance Williams and who could maximize the potential of the receiver who would find himself the old hand amid a rapidly changing team: Dez Bryant.

July 15, 2015: Re-Signing Dez Bryant

Prescott was taking first-team reps at quarterback during Cowboys training camp in 2016, which meant that his go-to target during drills was All-Pro receiver Dez Bryant; at 27 years old, he was the rare veteran starter whose career was still ascending. As they worked through the two-minute drill, Prescott executed a play from the 42 and hit Bryant on a short slant pattern, after which the receiver was supposed to immediately go down so that Prescott could quickly re-set, spike the ball to stop the clock, and then watch the field goal squad put up what, during a live-game situation, would be a winning kick. But Bryant saw an opportunity to score and burst toward the end zone. It didn’t work. If it had been an actual game, the Cowboys would have lost.

Prescott, a rookie with zero accomplishments in the NFL, approached the megastar. “You are the baddest man on the field, the best player on the team,” he said, according to Bleacher Report. “But you have to listen to me. I told you that you had to get down. Look what just happened. We have the best kicker in the league.”

Bryant, who had a reputation as a hothead, rose to the occasion—or maybe responded to something he saw in Prescott. “I got you, man,” he told the rookie. “It won’t happen again.”

There were times, earlier in his career, when it appeared that Bryant might not make it this far with the Cowboys. Despite his clear talent, he was only the twenty-fourth pick in the 2010 draft, thanks to what scouts and the media decried as “character concerns”—questions about a potential NCAA rules violation and about his childhood friends. Two years after going pro, he was charged with misdemeanor assault after police reported that he struck his mother during an argument (the charge was dropped after Bryant agreed to seek counseling). He had a tendency to shout at teammates during frustrating moments in games. In 2014, as he sought a new contract with the Cowboys, stories circulated in the media about the number of times that the police had been called to his house.

In previous years,the Cowboys had had a tendency to acquire big-name talent from other teams, rather than develop it internally. They signed star cornerback Brandon Carr on a free-agent deal after he left Kansas City, shipped off a bounty of draft picks to Detroit for wide receiver Roy Williams, and risked the team’s chemistry by bringing in notoriously high-maintenance receiver Terrell Owens. Moves like that rarely work in the NFL, but teams make them all the time in the hope that they know more about a player than the team that was willing to let him walk.

Building a team through the draft is much more effective than building through free agency, though. The teams that are perennially successful, like the Patriots and the Packers, tend to spend their free-agency dollars on their own stars. The Cowboys embraced this philosophy when it came to Bryant. Early in the 2015 off-season, they utilized an NFL rule called the franchise tag, which gives teams a window of time to make a deal to keep one of their stars who’s entering free agency, without that player getting offers from other teams. After several months of haggling, hours before the deadline to sign a long-term contract, Stephen and Jerry Jones flew to New York to meet with Bryant’s representation, a team that included Jay-Z and NFL “alpha agent” Tom Condon. With minutes to go, they signed a five-year deal. Bryant, then 26 years old, would be playing through his prime as a Cowboy.

What’s more, Prescott’s contract won’t come up until 2020, and Elliott’s won’t be due until 2021. Barring complications with Zack Martin, whose contract comes up after the 2018 season, the Cowboys’ roster of stars is young enough that the team can remain in an enviable situation for the next half decade or more. The entire philosophy of the team seems to have changed since the lost years of the late nineties and early aughts. “They’ve settled into something that’s based on analytics, on growing through the draft, managing the cap, and paying only the players you produce,” Sturm says. “They’ve gone from a team that was trying to figure out what the best teams were doing to a team that other teams are looking at and saying, ‘How are the Cowboys doing this? Let’s try to copy them.’ And that’s a massive departure over the last decade.”

Also this: the triplets are back, in the unlikely form of Prescott, Bryant, and Elliott. It’s a trio that no analyst—or, for that matter, Cowboys exec—could have drawn up on paper. But it’s a direct result of the new thinking in the front office. Fans used to wonder if Jerry Jones was the devil—but his son seems to be working miracles.