North Dallas Forty (1979) is widely regarded as one of the best football films ever made, although this is sort of like calling Friday the 13th a great movie about camping. There are maybe four minutes of football in the whole thing—most of it grimly executed, some of it downright brutal. You won’t find the usual lovable underdogs or fourth-quarter miracles, nor the kind of rollicking gridiron fun promised by the film’s zany, Mad magazine–style poster, where stars Nick Nolte and Mac Davis lounge triumphantly atop two cowboy boots, surrounded by adoring cheerleaders. In North Dallas Forty, football isn’t so much a game as it is a sinister presence, one that ruthlessly stalks its players, chewing them up and spitting them out before they’ve barely turned thirty.

Like M*A*S*H (1970) did for war, or The Hospital (1971) did for health care, North Dallas Forty sought to expose professional football as another gruesome branch of American capitalism, one whose working conditions would make Upton Sinclair retch. It follows the fictional North Dallas Bulls, whose players shoot themselves up with painkillers and limp out on shredded hamstrings just hoping to make it through another game, never mind winning one. Their heartless corporate owners grade their performances according to computer algorithms and hire off-duty police to spy on their extracurriculars. Football is a corrupt, dehumanizing system that we see through the bloodshot eyes of Bulls wide receiver Phil Elliott (Nolte), a pill-popping wiseass whose defiant attitude slowly builds into an allegorical rebellion against the Man. “It’s about the institution of football,” Nolte said during the film’s production. “Or about any institution.”

Specifically, North Dallas Forty is about the Dallas Cowboys—or at least, the version that appears in the 1973 novel of the same name by former Cowboys receiver Peter Gent.

After Gent’s roman à clef became a bestseller, then a movie, the media made its own sport out of matching its characters to Gent’s former teammates, even as he insisted his novel was a work of fiction. Nolte’s Phil Elliott, who we are repeatedly told has the “best hands in the game,” was clearly based on Gent (or, at least, on Gent’s considerable self-regard). His buddy, the Teflon-coated quarterback Seth Maxwell, played by Mac Davis, was a smooth-talking spin on O.G. Cowboys quarterback “Dandy” Don Meredith. (In fact, Gent said, they’d originally offered the role to Meredith himself.) And there was more than a glimmer of Tom Landry in head coach B. A. Strothers (played by G. D. Spradlin), a pious, humorless stiff who quotes from the Bible and IBM printouts with equal reverence.

Still, Gent wasn’t out to scandalize his old teammates. His novel used its Cowboys doppelgängers not just as a case study for the larger ills plaguing professional football, but as a representation, Gent wrote, of “the technomilitary complex that was trying to be America.” The book intermingles the Bulls’ locker-room drama with scenes drawn from civil rights riots and the Vietnam War, placing the athletes’ suffering—and the commodification of that suffering—along a broad spectrum of American callousness. Significantly, the story takes place in a Dallas that is still trying to shake off the Kennedy assassination and its festering image as a “City of Hate,” a convenient scapegoat for all the unease and violent impulses that were roiling the nation.

The movie cuts out most of that sociopolitical context, but by 1979, North Dallas Forty’s setting had only gained more symbolic weight. Dallas had, in essence, become the “capital of America,” as the writer Heather Havrilesky once argued in the New York Times. Americans yearning for a patriotic grandeur and frontier spirit that could lift them out of their seventies malaise had found it in the take-no-prisoners exploits of J. R. Ewing on Dallas, which debuted the year before. Dallas, both the real and the fictional place, were emblems of the old American myth of Jay Gatsby–like reinvention and the curative powers of capitalism. As J. R. himself said, “All that matters is winning.”

It was a philosophy shared by the Cowboys’ Tom Landry: “Take away winning, and you take away everything that is strong about America,” Landry mused to Texas Monthly in 1973. “If you don’t believe in winning, you don’t believe in free enterprise, capitalism, our way of life.” By 1979, the Cowboys weren’t just winners, boasting two Super Bowl championships and more regular-season victories than any other team that decade. They’d become something like folk heroes—“America’s Team,” as they’d been christened just a year earlier, led by Roger Staubach, “Captain America” himself. Much as the Texans of old Westerns had once embodied American exceptionalism through their hardy self-reliance and epic cattle drives, America’s Team had captured the national imagination with its Doomsday Defense and string of division titles. The cowboy myth had given way to the Cowboys myth. And North Dallas Forty threatened to dismantle it.

Despite its Texas setting, North Dallas Forty was shot entirely in Los Angeles. Co-screenwriter Frank Yablans claimed to Roger Ebert that it was just faster and cheaper that way. But former New Orleans Saints coach Tom Fears, one of the film’s technical advisers, would later tell the Washington Post that the crew “weren’t welcome in Dallas”—that the Cowboys had exerted their considerable influence to keep the production from even renting out the Cotton Bowl.

Without any recognizable backdrops, even on the B-roll, North Dallas Forty doesn’t feel like an explicitly Texas movie. It’s also not especially clear whether a lot of its characters are supposed to be genuine Texans or simply free agents. Nolte, for example, may dip into a slight drawl here and there, but mostly he just downshifts into that grumbling, hungover gear that he would grind in for the rest of his career. And there are only a handful of actual Texans in it, including Huntsville’s Steve Forrest and native Texan Dabney Coleman as the Bulls’ co-owners Conrad and Emmett Hunter—a very loose (and not especially flattering) portrait of original Cowboys owner Clint Murchison Jr. and his brother, John.

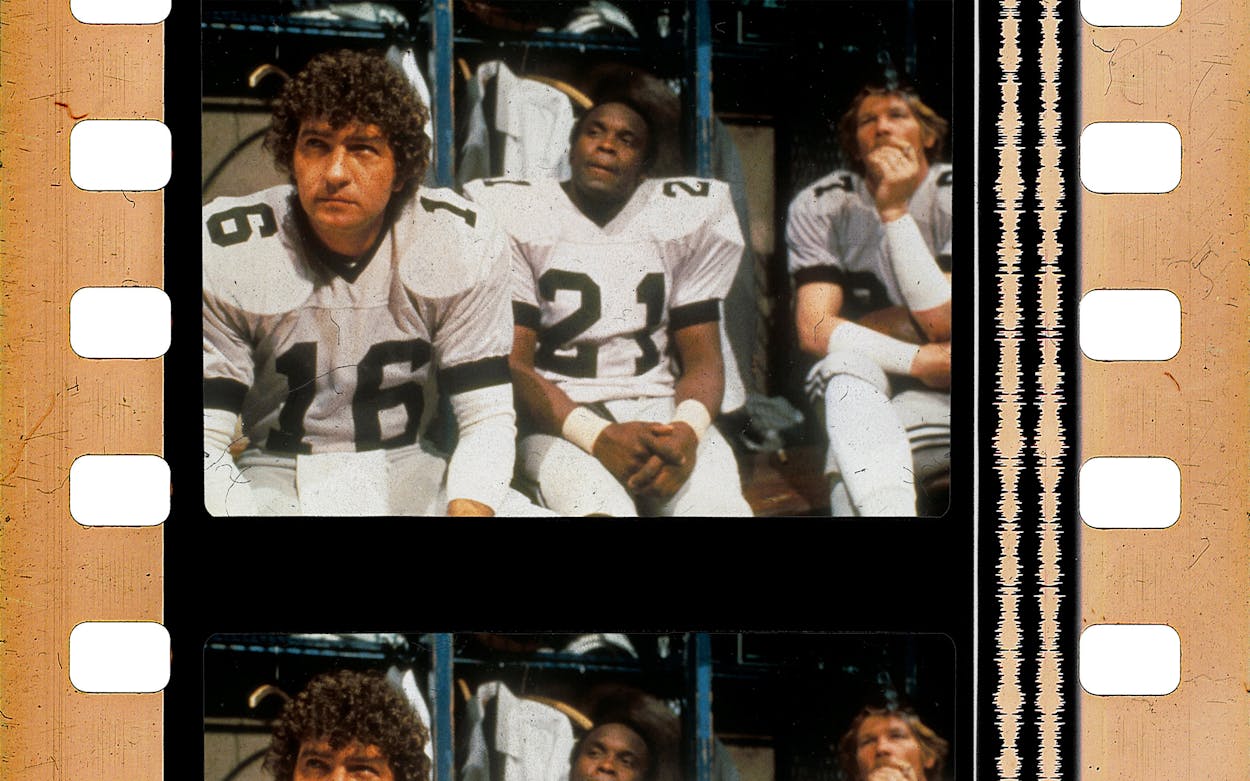

But then there is Mac Davis, the Lubbock native who was then (and likely still is) best known as a country singer. Before North Dallas Forty, Davis had only acted in a few light comedy sketches on his eponymous variety show, but he brought an impressively surefooted confidence to his feature film debut. As Seth Maxwell, Davis is cool and unflappable, adopting a cheerful stoicism that proves a welcome counterbalance to Elliott’s constant bellyaching. He can be downright blasphemous in a state that treats football like a religion: In the film’s most memorable scene, Maxwell downs a breakfast of beer and codeine, then gaily recounts a night he spent inspiring some local kids at the YMCA—“I gave them my usual bullshit, you know, football, character development, all that crap”—before segueing into a graphic retelling of his subsequent romp with a prominent booster’s wife. He’s oily and untrustworthy, always and only looking out for himself. But he’s also the only one who seems to be having a good time.

In fact, I dare say that Seth Maxwell is the sort of Texan that I think, deep down, most of us aspire to be. He was certainly the kind of Texan that was so admired by the film’s late-seventies/early-eighties audiences, who dressed in “Texas chic” and adopted the do-whatever-you-damn-well-please attitude of the urban cowboy. Much as Dallas had inadvertently made an aspirational figure out of J. R. Ewing in the age of greed, North Dallas Forty tries to position Maxwell as the not-so-secret villain of the piece. Yet in the end, it’s hard for anyone—for Phil, for the audience—to resent him. He’s just too damn likable, and unlike Elliott, he’s savvy enough to make his cynicism work to his advantage. “You had better learn how to play the game, and I don’t mean just the game of football,” he tells Elliott early on. “Hell, we’re all whores, anyway. We might as well be the best.”

Although not expressly about Texas, North Dallas Forty can’t help but traffic in a few of its tropes, like Elliott harboring a secret dream about running a horse farm. The Bulls’ oilmen owners, with their game-day Stetsons worn over stiff gray suits, belong to that archetypal “Big Rich” breed of arrogant Texas businessmen. And while most of the actors get to spend the movie wearing sweatshorts—or nothing—Davis is twice possessed by a chewing tobacco ad, slipping into a thick white turtleneck, pearl-snap denim shirt, and sherpa-lined hunting vest that’s topped off by a big brown cattleman.

The film’s most egregious Texas stereotype is the Bulls’ hulking offensive lineman, a priapic gorilla who sexually assaults every woman he meets—and who has, of course, been given the ur-Texan name of “Jo Bob.” Jo Bob is played by the Swedish actor Bo Svenson, a slander that surely violates some international convention.

For all the anticipated controversy when it was released nearly 45 years ago, North Dallas Forty caused only a minor stir within the NFL. Several of the real-life players who had either appeared in the film or served as its technical consultants told the Washington Post that they’d ended up being “blackballed” from the league, even as the NFL’s then-commissioner Pete Rozelle blasted their claims as ridiculous. But whatever league-wide reckoning was predicted never really arrived—at least, not due to anything revealed by the film.

The Dallas Cowboys themselves pleaded a sort of amused ignorance, copping to some of the funnier bits as based on true events, but largely shrugging off Gent’s depictions of drug abuse as exaggerations perpetrated by, to quote team president Tex Schramm, “a sick man.” Mostly, the Cowboys, as they always seemed to do back then, simply floated above it. Three months after the film’s release, Roger Staubach played his final game, and arguably this did more to hasten the end of the myth of “America’s Team” than the movie ever did. Looking back now, you could even say the film ended up creating a new Cowboys myth, one that portrayed its players not as square-jawed, Staubach-ian heroes, but as lovable scoundrels with a distinctly Texas swagger.

There’s a certain nostalgia to that these days, especially when there’s just not much left of the “Dallas Cowboys myth” to speak of (unless you mean the annually renewed optimism that they could be Super Bowl contenders). Under the glare of Jerry Jones’s JumboTron, today’s Cowboys, along with the rest of the NFL, are so obviously a brand that it’s a wonder anyone ever thought differently. Much as the bloodied noses and dislocated elbows of North Dallas Forty now seem positively quaint, relics of a world before everyone knew the term “CTE,” there’s a certain rowdy innocence to the Bulls’ antics, a reminder of a time when football still had an unpredictable rawness and personality.

In one of North Dallas Forty’s many climactic speeches, a Bulls lineman berates his coaches, shouting, “Every time I call it a game, you call it a business. And every time I call it a business, you call it a game!” This felt like a call to arms when the film was released, a cry against the shifting tides. Now, the natural reaction would be a dispirited “well, duh.” Of course football is just a business, along with everything else about this late-capitalist dystopia we live in. Like Seth Maxwell says, you’d best learn how to play it.

Most “Texas” scene

In the film’s raucous opener, Nolte’s Elliott is soaking his bruises in a morning bath when Maxwell, Jo Bob, and several of their teammates suddenly kick in the door, blast a shotgun into the ceiling, then haul him off for a morning hunting trip spent downing Budweisers on the hood of a Cadillac and shooting at cows. It all sounds like a cartoonish exaggeration, until you read that former Cowboys lineman Larry Cole admitted it was at least partly based in reality.

Most “Texan” dialogue

Naturally, it’s Davis who lends North Dallas Forty many of its authentic Texan flourishes, such as his ad-libbed nickname for Elliott, “Poot,” a term that, as Gent helpfully noted, was a “Texas nickname” meaning “fart.” Davis is also fond of dropping other distinct—and distinctly scatological—breeds of colorful Texas sayings, comparing another player to “a one-legged cat trying to bury shit on a frozen pond” and asking (rhetorically), “Does a shark shit in the sea?”