Former San Antonio Mayor Julián Castro has spent 2017 preparing for what now looks like an inevitable run for president. But for Castro, a Democrat, the road to the White House doesn’t pass through his deeply red home state. Instead, it winds through Arizona, where he is speaking this Saturday at the Maricopa County Democratic Party winter convention in Phoenix.

When the question of presidential candidacy has been put to Castro, he’s consistently demurred, but he has also said he’ll decide by the end of the year whether he wants to run. In the meantime, he’s created the “Opportunity First” political action committee (named for his favorite catchphrase) in order to raise money for other Democratic candidates, and one surefire way to cultivate a political base is to support candidates in those states needed to win the presidential primary.

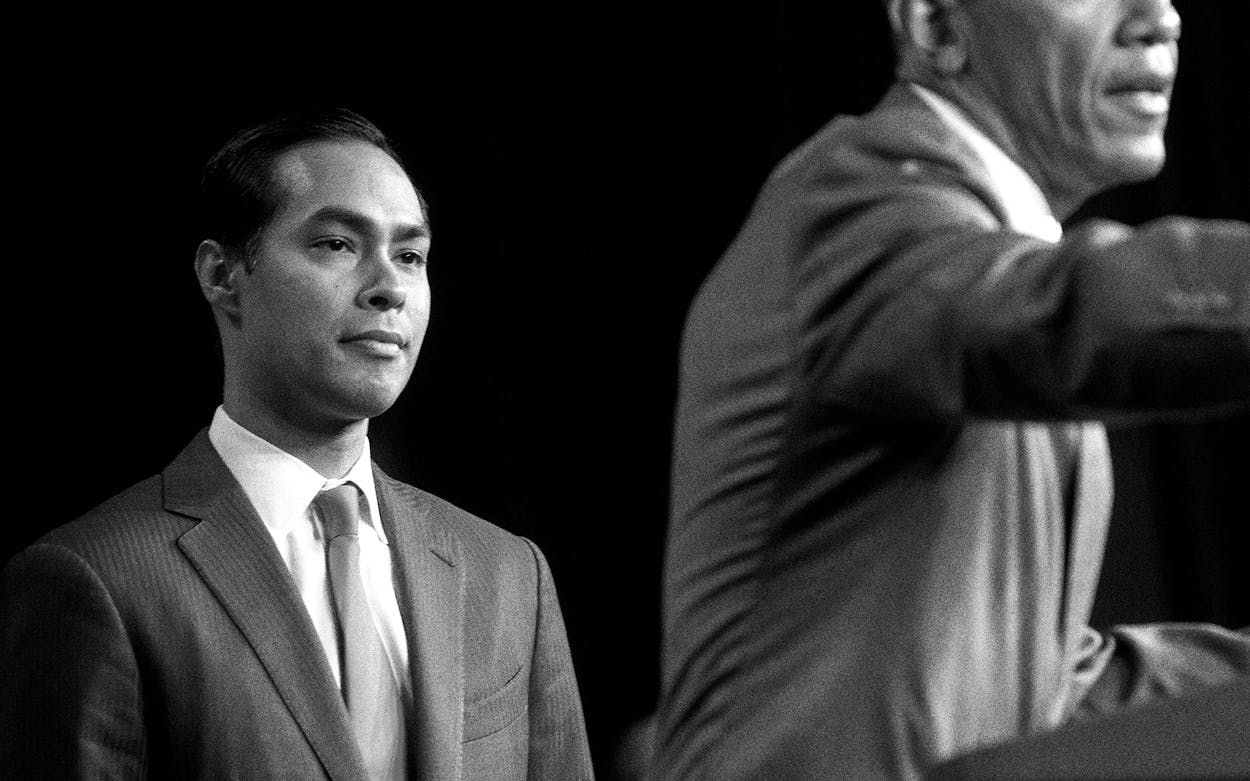

Castro has also spent the fall completing a personal memoir that he’d put on hold while serving as President Obama’s housing secretary. Political memoirs by second tier presidential contenders don’t necessarily sell, but they do provide an excuse to travel the country, meet potential supporters, and hone a message without the kind of media scrutiny that inevitably comes with being a top candidate.

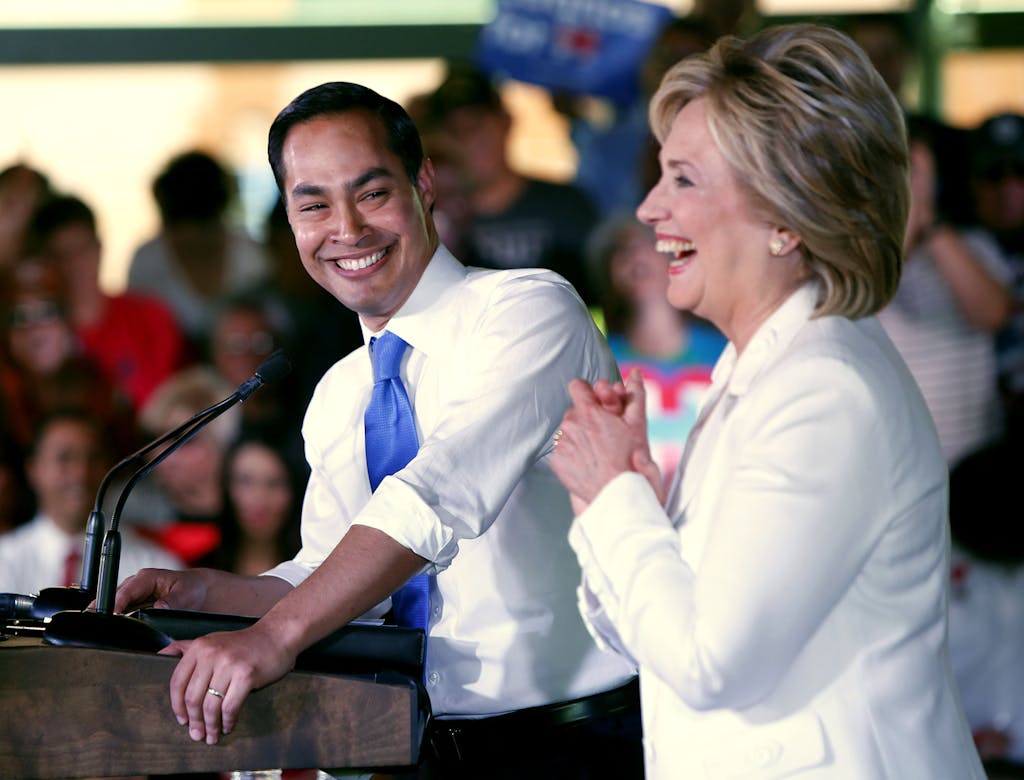

Though this has been a year of intensive planning, Castro’s campaign for the White House actually began in May 2015, with a not-so-quiet effort to become Hillary Clinton’s running mate. Youthful and telegenic, Castro was touted as the Latino Barack Obama—a political unknown who was thrust into national prominence by a Democratic National Convention keynote address and an autobiographical book tour.

The Castro camp has largely followed Obama’s script, even if they’ve been slightly less ambitious. Although relatively unknown nationally, in 2012 Castro became the first Latino to deliver the keynote address at the Democratic National Convention. He then secured the deal to write a memoir, and President Obama chose him to serve as secretary of housing and urban development. Castro was clearly a rising star. Latino politicians from San Antonio to New York endorsed him for Clinton’s ticket, and Castro hosted a Latinos for Hillary event in San Antonio in October 2015. At a U.S. Hispanic Chamber of Commerce meeting earlier that day, Clinton even hinted that he may become her vice presidential choice: “I am going to look really hard at him for anything, because that’s how good he is.”

But then Donald Trump, with his harsh rhetoric about building a border wall and deporting undocumented immigrants, changed her campaign calculus. Clinton believed courting the Hispanic vote was less urgent because Trump would motivate them himself. In addition, just days before Clinton made her vice president pick in July 2016, the U.S. Office of Special Counsel reported that Castro had violated the Hatch Act by promoting Clinton while serving as a public official. The night before Clinton announced U.S. Senator Tim Kaine of Virginia as her choice, campaign chair John Podesta called Castro to deliver the bad news: it wasn’t going to be him.

“It’s disappointing, of course,” Castro told Dan Balz of the Washington Post, “but it’s also easy to put into perspective. When I was 30 years old, I lost a very close mayor’s race. At the time I was completely disappointed and crushed. But a few years later I came back and I became mayor of San Antonio and it actually worked out for the better.”

In Clinton’s campaign memoir, What Happened, Castro is not even mentioned by name. She merely writes that she chose Kaine as her running mate “out of a superb field of candidates.” But if Clinton had gone with Castro, he might have provided the boost needed to carry both Arizona and Florida, thereby tilting the Electoral College tally to a Clinton victory.

Yet whatever disappointments or missed opportunities Castro suffered in 2016, he is now looking forward to 2020. By the end of this year, he’s expected to announce that he’s exploring a run for the Democratic presidential nomination. Conventional wisdom suggests that Castro is really trying to position himself for another shot at vice president. But his long-time mentor, former San Antonio Mayor Henry Cisneros, told me that Castro can’t settle on running for second place. If Castro runs, he must seek the top prize.

“I don’t think you run for vice president,” Cisneros said. “If you’re going to put your name on the line for president, you don’t want to do it halfway, and you don’t want to do it where you look bland and unenergetic, low energy. You’ve got to expend all your energy to look as good as you can for the country.”

Cisneros said Castro has a slew of qualities that make him attractive as a presidential candidate: he’s bright and knows the nuances of public policy; his values align with average Americans; he understands the changing national economy; and he is a man of high personal character. “I believe he feels like anything can happen in a year like this, in a period like this,” Cisneros said. “So, given the stakes and given the size of the prize, it’s worth pursuing the top prize.”

In early November, Castro told a Voto Latino conference in Austin, “There are three dozen Democrats that are looking, but I will tell you that we need a very different kind of president than we’ve had.”

Three dozen is a slight exaggeration, but Washington-based political reporters can easily conjure a list of 20 contenders, leading off with U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders and former Vice President Joe Biden. Starting two years before the election may seem early, but not if you’re following the Obama playbook and want to break ahead of the pack.

Of course, one of Castro’s first obstacles is that Texas has delivered its Electoral vote to a Democratic presidential candidate just once in his lifetime—in 1976, when Castro was two. Given the opportunity to seek statewide office in 2018, neither Castro nor his twin brother, Congressman Joaquin Castro, chose to run. And for many national donors and political pundits, that signals weakness.

The early 2020 primary and caucus calendar will also work to Castro’s disadvantage. The Iowa caucuses and primaries in New Hampshire and South Carolina all occur in February, and those states lack a substantial Latino voter presence. Castro’s first real opportunity wouldn’t occur until Nevada, which is close to the end of the month. But on Super Tuesday, March 3, 2020, both Texas and California—and their large Hispanic populations—are scheduled to hold Democratic primaries. March would also include two more contests that could potentially favor Castro: Arizona and Florida.

Puerto Ricans will have a significant impact in Florida—since Hurricane Maria devastated the island, more than 73,000 people have flocked to Florida—and already, Castro has done more than Clinton to secure and motivate the Puerto Rican vote. As HUD director, he visited Puerto Rico in May 2016 to discuss affordable housing and the spread of Zika. And in June 2017, he tweeted that “Puerto Rico should be admitted as a state to the United States.”

Still, Matt Barreto, a University of California at Los Angeles political scientist and founder of the polling firm Latino Decisions, told me it makes sense to Castro to ease into the contest by starting with a book tour, like Obama did. “You have people like Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, even Kamala Harris, who are in a different category. They’re sitting U.S. senators. They already have a large national platform. They can essentially book themselves on any cable news show anytime they want,” Barreto said. “So if you’re not a currently elected official, such as Castro, then you need to find opportunities to sort of inject yourself into the news narrative.”

The mere fact that Castro could not carry Texas in a presidential election will not count against him if he becomes a strong Latino presence as a candidate. “Castro doesn’t need Texas to win. The Democrats don’t need Texas to win,” Barreto said. “What he potentially could do, assuming he has strong support and is able to galvanize enthusiasm in the Latino electorate, is make Arizona a battleground state, which it’s already trending that way.

“That makes Castro’s potential candidacy, whether it’s at the presidential or vice presidential level, interesting.”