Once a week, Adrian Billings drives his white Chevy pickup from his home in Alpine, Texas, to Presidio, a city along the Mexican border. This summer he’s been taking his son Blake, who’s home from college, with him. The drive, through mountains and desert on a two-lane highway across which actual tumbleweeds roll, takes an hour and a half.

Billings is a family doctor, one of only a handful in this part of West Texas. He offers a one-stop shop for his patients’ ailments: heart murmurs, kidney stones, et cetera. Most of the time he works in Alpine or the nearby city of Marfa. But he makes the weekly drive to Presidio, because without doctors like him, it wouldn’t have medical care. There’s no hospital and no full-time doctor. His clinic, which opened in 2007 with the help of government grants, is the only access residents have to even a local pharmacy.

Presidio is poor. The median household income is $20,700, one of the lowest in the U.S., though still well above Texas’s miserly Medicaid income eligibility limits. “We have a lot of uninsured patients here,” Billings says. Because of this, he sees many cases of unmanaged diabetes and high blood pressure. He also sees a lot of pregnancies. On a sunny Thursday in early June, Billings wheeled out a sonogram machine donated by a charity a few years ago and confirmed that a young woman was pregnant. She was happy—she wants to have a baby. But in West Texas, that’s easier said than done.

Billings explained, as he does to all pregnant patients, that he can use the machine to detect a fetus, but he can’t do much else. The clinic doesn’t have a sonographer with the expertise to ensure one is developing properly. Normally he’d recommend the woman drive the hour and a half to Big Bend Regional Medical Center, Alpine’s hospital, for her prenatal needs and to give birth. But for more than a year, Big Bend’s labor and delivery unit has closed routinely, sometimes with little notice. Some months it’s been open only three days a week.

Big Bend is the only hospital in a 12,000-square-mile area that delivers babies. If Billings’s patient goes into labor when the maternity ward is closed, she’ll have to make a difficult choice. She can drive to the next nearest hospital, in Fort Stockton, yet another hour away. Or, if her labor is too far along and she’s unlikely to make it, she can deliver in Big Bend’s emergency room. But the ER doesn’t have a fetal heart monitor or nurses who know how to use one. It also doesn’t keep patients overnight. When a woman gives birth there, she’s either transferred to Fort Stockton—enduring the long drive after having just had a baby—or discharged and sent home.

This situation is stressful and dangerous for pregnant women. Uterine hemorrhages, postpartum preeclampsia (a potentially deadly spike in blood pressure), and other life-threatening complications are most likely to occur in the first few days after childbirth. This is why hospitals usually keep new mothers under observation for 24 hours to 48 hours. “This is not the ‘standard of care’ that women should receive,” Billings says. “You’re not supposed to discharge patients and leave it up to chance.”

Big Bend doesn’t really have a choice. In the past two years, almost all its labor and delivery nurses quit. The hospital has tried to replace them, but the national nursing shortage caused by the pandemic has made that impossible. When Big Bend is too short-staffed to deliver a baby safely, its labor and delivery unit has to close.

Since 2020, dozens of hospitals have closed or suspended their maternity services. In Florida, so many hospitals have stopped delivering babies that the only facilities left are in and around cities, leaving rural counties entirely without maternity care. “Having a place for people in your community to give birth is just a basic service,” says Katy Kozhimannil, a professor of health policy and management at the University of Minnesota who specializes in rural maternal health. “You can’t have a functioning community without it. And yet it’s increasingly seen as extra. The burden of pregnancy and birthing is getting exponentially harder in this country. At a certain point it’s like, what are moms supposed to do?”

As with other chronic social conditions, COVID-19 has exacerbated the closing of maternity wards. But it didn’t cause it. Access to maternity care in the U.S. has been declining for decades. It isn’t just a rural problem either. In the past twenty years, more than a dozen hospitals in Philadelphia have shuttered their maternity wards, leaving the city, in which about 20,000 women give birth annually, with five hospitals to serve them. In 2017 two hospitals that served primarily low-income women in Washington, D.C., closed their maternity wards within months of each other; nearby hospitals were so overrun by displaced patients that women ended up in labor on gurneys in hallways. But in rural communities, where there’s no secondary hospital to absorb patients, the situation is dire. Since 2004, rural maternity wards have closed at a rate of about 9 percent per decade. According to research from the Chartis Center for Rural Health, only 46 percent of rural counties now have a hospital that delivers babies.

Before the pandemic, the primary cause of maternity ward closures was cost. Childbirth is the most common reason for a woman to be hospitalized, and wards have to be fully staffed around the clock because babies don’t arrive on a predictable schedule. This makes maternity care the largest expenditure for many hospitals.

Medicaid pays for 42 percent of all hospital births, but it doesn’t reimburse hospitals for the full cost of care. (In most states it pays between 50 cents and 70 cents on the dollar, which means a hospital loses money when it cares for someone on the program.) To offset its losses, a hospital often charges its privately insured patients significantly higher fees. But if it’s in a poor neighborhood and doesn’t have enough privately insured patients, it can’t recoup the money. So most pre-pandemic maternity ward closures were in low-income areas and disproportionately affected pregnant women of color. Pandemic-related nursing shortages have only made the situation worse. Nowhere is this problem more evident than in Texas.

The state is the national leader in maternity ward closures. In the past decade, more than twenty rural hospitals have stopped delivering babies. More than half the state’s rural counties don’t even have a gynecologist. Texas has some of the lowest income eligibility limits for Medicaid and has declined to expand them, as allowed by the Affordable Care Act. (Childless adults don’t qualify for the program unless they’re disabled.) As a result, more than 18 percent of Texans don’t have health insurance, the highest percentage of uninsured residents in the U.S. Income eligibility limits jump for pregnant women—$36,200 for single mothers, $45,600 for married ones—but the application process takes at least a month. According to the March of Dimes, a fifth of all pregnant women in Texas don’t get prenatal care until they’re five months along. In other words, when a poor woman gets pregnant in Texas, it’s hard for her to find a doctor or even a hospital.

“What we’re seeing in terms of health outcomes, it’s not good,” says John Henderson, chief executive officer and president of the Texas Organization of Rural & Community Hospitals. “We have lower birth weights, more preterm births. When it comes to caring for pregnant women and their babies, Texas does not compare favorably to other states.”

The effects of this erosion of women’s health care are difficult to quantify. There’s no national survey of postpartum complications—hospitals don’t track them, and neither do insurance companies. “It’s hard to know what women are going through after childbirth, because no one collects data,” says Julia Interrante, a maternal health researcher also at the University of Minnesota, which has one of the best-regarded maternal health research programs in the U.S. The only real number to go on is one ominous figure: how many women die.

For every 100,000 women who give birth in Germany, fewer than 4 die. In Canada, the figure is 8; in the UK, a bit fewer than 9. In the U.S., the number is 24. In 2020, 861 women died because of pregnancy or childbirth. That may not sound like a lot, but according to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, for every death, an estimated 70 other women barely survive. This means that in 2020, an additional 60,270 women in the U.S. suffered life-threatening medical complications, many of which could’ve been prevented if they’d had better access to care. Ranked against other countries by the World Bank, the quality of maternal health care in America is no better than in Latvia, Moldova, and Oman.

It wasn’t always this way. Forty years ago, America’s maternal mortality rate was 7.5, better than in many European countries at the time. But while childbirth has gotten safer there, today the U.S. is the most dangerous wealthy country in which to give birth. And in the absence of data, nobody has a comprehensive explanation. “That’s the million-dollar question,” Interrante says. “There are theories, but right now no one really knows.”

The maternal mortality rate isn’t the whole story. It doesn’t parse the racial inequities that lead Black women in the U.S. to be three times as likely as white women to die in childbirth. Nor does it get at the fact that women over forty are much more likely to endure complications than women younger than thirty—a concerning issue as more women delay having children until they’re established in their careers. And it doesn’t touch on one of the biggest risk factors of all: where someone lives.

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the maternal mortality rate in cities is about 18 deaths per 100,000 births. In rural counties, that figure is 29, roughly on par with Syria. Babies are more likely to die, too. Insufficient prenatal care is linked to a greater likelihood of preterm birth, the leading cause of infant death in the U.S. Because most rural hospitals in America don’t have a working maternity ward, women travel longer distances to give birth, putting them at greater risk of delivering on the side of the highway or at home without a medical professional. The CDC estimates that infant mortality rates are 20 percent higher in rural areas than in large urban ones.

These problems aren’t unique to the U.S. People living in remote areas of every country struggle with access to health care. But when it comes to giving birth, other countries have come up with contingency plans. In Australia, France, and the UK, among others, babies are often delivered by midwives rather than obstetricians, whose surgical expertise is reserved for high-risk pregnancies and cesarean sections. The U.S. is again an outlier, with midwives delivering only 8 percent of babies, compared with more than half in the UK and the Netherlands. Midwives often fill gaps in care for women who live far away from a hospital. In the Canadian province of Ontario alone, there are at least 23 different rural midwifery groups catering to remote communities, a figure that’s grown in recent years. In Australia, which relies on a network of birthing centers, some states even offer transportation or reimbursement for people who have to travel more than one hundred kilometers (62 miles) for medical care. None of these solutions is perfect—in the Australian outback, for instance, birthing centers fill up quickly, and they don’t offer epidurals—but at least they’re something.

Unlike some American states, Texas recognizes midwives as medical practitioners. But according to a 2018 survey in the Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, most work in large cities. Through the State Office of Rural Health, Texas offers grants and other funds to bolster the rural health-care workforce, but they come to about $3.5 million per year, or just $1 for every person who lives in a rural area. And studies link Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act (which, again, Texas declined to do) to better financial stability for hospitals and better outcomes for mothers and babies, because more women don’t have to wait until pregnancy to qualify for the program.

The focus in Texas has been on abortion. Last year the state essentially banned the procedure with a law that threatens doctors with prison time for performing one. In late July, after the reversal of Roe v. Wade, Texas attorney general Ken Paxton sued the Biden administration. Paxton argued that the state shouldn’t have to abide by an administration directive that a 1986 federal law supersedes state laws and requires doctors to perform emergency procedures, including abortions, to save the life of the mother.

A study released last year by the University of Colorado estimated that a federal ban on abortion would cause maternal mortality to rise 21 percent, causing 140 more women to die in the U.S. each year, most of them Black. In June a New England Journal of Medicine survey of 25 Texas clinicians found that the threats of prison and lost medical licenses have created a “climate of fear”—and led to delays in treatment for life-threatening complications until women were, according to one doctor, at “death’s door.”

In other words, providers say, instead of working to better the state of maternal health care for the mothers and babies who exist, Texas is pursuing policies that will likely make a bad situation even worse. “The lack of investment by the state,” Billings says, “the lack of funding for rural health care—what we’re putting patients through because of this—to me, I think it’s unconscionable.”

Ask any of the six thousand people who live in Alpine, and they’ll tell you it’s a great place to settle down. It sits on a high plateau between desert mountain ranges that keep summer temperatures bearable. Surrounding a few blocks of downtown shops are streets full of low-slung ranch houses with front yards full of cactuses and red dirt. “It’s safe, quiet, friendly,” says Kelly Jones, a stay-at-home mom of two.

The U.S. Border Patrol and county sheriff’s office keep many residents employed. There’s a movie theater, an Amtrak station, a small university (a former teacher’s college), and a baseball field that’s home to the Alpine Cowboys, who are part of the regional Pecos League. For fine dining and culture, Marfa is 26 miles away. In recent years, Marfa has become a wanderlust destination for coastal urbanites looking to sip $15 cocktails and take selfies in the middle of nowhere. Alpine doesn’t draw as many tourists, but its doughnut shop is famous for throwing in an extra one with every order.

As quaint as Alpine is, it has some drawbacks. It’s three and a half hours from El Paso and more than five from San Antonio. There’s one grocery store, and the closest Walmart is an hour away. There’s no day care, which makes it hard for businesses to recruit families with two working parents.

“We’ll hire a nurse who’ll say, ‘Great, I can start work in two weeks. Just let me get day care set up.’ We tell them, ‘Well, we don’t have day care in Alpine.’ They’re like, ‘What are you talking about?’ They can’t accept the job,” says Roane McLaughlin, Alpine’s only obstetrician and gynecologist. Before she moved to the area in 2014, Alpine didn’t have an ob-gyn at all. For a long time, it didn’t offer epidurals. “We did a lot of C-sections for what’s known as ‘intolerance of labor,’ ” Billings says, “when the pain was too much.” Only in 2010, after enough privately insured patients called the hospital’s then-CEO and threatened to give birth elsewhere—a strategy that Billings says he masterminded by giving out the CEO’s phone number—did Big Bend finally offer them.

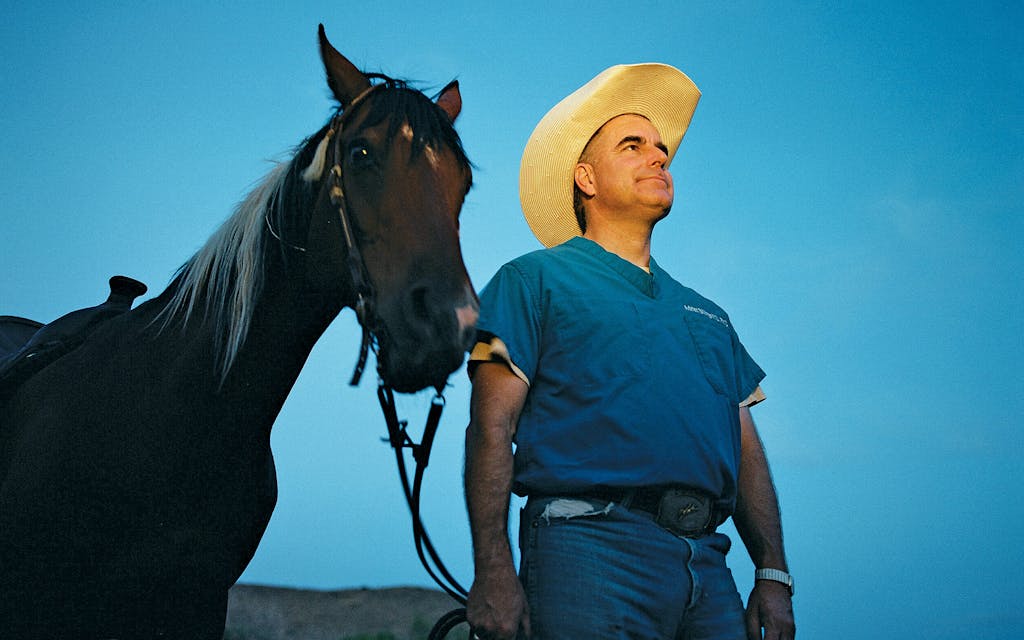

Billings, 51, first came to Alpine as a medical student. His tuition to the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston was paid by a National Health Service Corps scholarship that required him to practice medicine in a rural area for at least four years. He grew to love the remoteness and in 2007 moved to Alpine permanently and opened his own practice. Now he runs Preventative Care Health Services, a federally qualified health center, which receives government grants for providing primary care to underserved populations. The clinic employs six other doctors, two of whom—Katie and John Ray, who are married—also deliver babies. When these doctors tell stories, they sound like wartime medics in a MASH unit.

There’s the time a woman’s undiagnosed ectopic pregnancy ruptured her fallopian tube, and she had too much internal bleeding to be safely transferred to the larger, nicer hospital in Odessa for surgery. “The only option she had was me,” Billings says. “I went to her bedside and told her, ‘Listen, I don’t do this kind of surgery, but I do know C-sections. I’m fairly certain I can pull you through this.’ ” And he did.

Or the time James Luecke, a family practitioner in private practice who’s been delivering babies in Alpine for more than thirty years, had a woman show up at the hospital with her fetus’s foot hanging out. She’d traveled for hours while in labor to get there and had no prenatal care, so Luecke didn’t know how far along she was—or, as he discovered performing an emergency C-section, that she was carrying twins. “I’ll always remember that one, because it happened on Mother’s Day,” he says.

Or when Katie Ray had a patient go into labor at 26 weeks. (A full-term pregnancy lasts 40.) Big Bend has no neonatal intensive-care unit, so it can’t care for babies born before 35 weeks, though its labor and delivery nurses are trained in emergency neonatal resuscitation. When someone delivers prematurely, the baby has to be medevaced to Odessa or El Paso. The woman’s labor progressed until her cervix was seven centimeters dilated (at ten, a baby can be born), and then, inexplicably, it stopped. In an ideal situation, Ray would have kept her patient in the hospital and let the fetus gestate to increase its chances of survival. But that could have taken days, and the medevac team couldn’t wait around indefinitely.

“I was like, ‘Well, can you take her with you?’ ” Ray recalls asking the team. “They’re like, ‘No, we can’t. She could deliver on the plane, and that baby would definitely die.’ ” A baby born at 26 weeks with access to a NICU was more likely to survive than one born at 27 weeks without it. So Ray performed a C-section and put the baby on the plane. She heard later the child survived. “It was just an impossible call,” she says. “We have to make really weird decisions sometimes. But that’s what I signed up for when I came to this place.”

What Ray didn’t sign up for, she says, was a maternity ward that would close its doors and turn away patients, which is what Big Bend has done for more than a year. “If you go into labor and the hospital is closed, you’re SOL,” she says. “Or say you deliver when the hospital is open, but it’s closing in seven hours. Do we just discharge a seven-hour-old baby? That’s what we’re doing. Our back is against the wall.”

Big Bend Regional Medical Center entered the pandemic with eight labor and delivery nurses. Technically that meant it was fully staffed, though just barely. If someone took a day off or got sick, there was no one to replace her. Despite its sparse population, Alpine and the surrounding area was hit hard by COVID. In December 2020, it was briefly one of the top twenty places in the country with the most confirmed cases per capita.

With only 25 beds, the hospital was quickly overwhelmed. “I took care of a lot of patients who really should have been sent somewhere else, but we couldn’t find anyone to take them,” Billings says. Patients were waiting as long as a week to be transferred, then sent as far away as Louisiana and Oklahoma because the hospitals in Texas were full. “Not everyone made it,” he says.

More than 87 percent of nurses in the U.S. are women, and it’s no different in Alpine. When schools closed and children switched to remote learning, Big Bend’s nurses found themselves pulled in two directions. With no child-care options, they had to stay home. But colleagues were falling ill, and the hospital administration was asking people who were still healthy to work overtime. Those without kids, or whose kids were already grown, did what they could—but it wasn’t enough. “I was coming in seven days a week, twelve-hour shifts. I just got burned out,” says Karen Ramirez, who’d been a labor and delivery nurse at the hospital for 21 years before quitting in July 2021. To cover its mounting staff shortages, Big Bend had to shuffle nurses around, putting a labor and delivery nurse in the ER and vice versa, a move that horrified nurses.

“These are specialty professions,” says Donna Hernandez, a former ER nurse who quit in November 2020. “You can come to me to save your life, but I don’t know how to deliver your baby.” Several nurses say that when they spoke up about what they considered to be unsafe working conditions, Big Bend’s CEO, Rick Flores, told them that they were lucky to have a job and that if they quit, they’d be easy to replace. “That’s not good for morale,” Ramirez says. “I left the job because of that.” (“This is not true,” Flores said in a written statement. “I have reminded staff about our responsibility to the people of Alpine, to each other, and our profession.”)

When it was really short-staffed, the hospital turned to travel nurses, freelancers on thirteen-week contracts. It was an expensive solution—travel nurses routinely make two or three times a staff nurse’s salary—and an impractical one. A travel nurse’s contract is so short that by the time she’s grown familiar with her new workplace, she’s out the door.

“They were so overwhelmed in Alpine. I’d never seen anything like it,” says Haley Personna, a labor and delivery travel nurse who worked at Big Bend from November 2020 to February 2021. “My first day, I met with HR for maybe ten minutes, then they put me on the floor with my own patient. I didn’t get so much as a ‘Hey, here’s where the supply closet is.’ They were that understaffed.” (Flores responded that “travel nurses already have experience in their specialty.”)

At the time, Big Bend, along with what seemed like every other hospital in the country, was looking for nurses. So many quit their jobs during the pandemic that in a recent survey of about 12,000 nurses by the American Nurses Foundation, 89 percent said their workplace is still chronically understaffed. There weren’t enough travel nurses to go around, and Alpine’s child-care problem made it hard to attract the few there were.

On July 5, 2021, Big Bend closed its labor and delivery unit for the first time. From then on, it would be open only a few days a week, usually Monday through Wednesday. Technically it went on what’s known in the industry as “diversion,” which is the practice of sending patients to hospitals with the capacity to care for them. But in practical terms, the unit was closed.

It would be one thing if Big Bend’s part-time schedule was consistent. But staffing shortages aren’t always predictable. The hospital tries to set its diversion calendar a month out, but doctors say it’s never accurate. “It’s definitely not consistent. Every week is different,” Ray says. Recently she had a patient go into labor on a Tuesday, when the unit should’ve been open, but it was closed. “They gave us no warning. They were literally just like, ‘Oh, we’re on diversion.’ It’s like, how is this the plan, guys?”

More of the hospital’s longtime staff quit out of frustration. At one point, it was down to only three labor and delivery nurses. One of them, Dani Bell, started giving her phone number to nurses in other units so they could call if they needed help with a complicated delivery. A travel nurse who’d just joined the hospital once called her because a woman was about to give birth at 25 weeks in the ER, and the nurse didn’t know where any of the supplies or equipment were kept. “I came in that night to help her. Everything turned out okay. We got the baby shipped out” to El Paso, Bell says. “But it just started this feeling. I was coming home from work exhausted. I was barely seeing my kids. Why was I doing this to myself?” She quit in December 2021.

Meanwhile, Pecos County Memorial Hospital in Fort Stockton, the closest one to Alpine, couldn’t always take Big Bend’s diverted patients. During the delta wave last summer, Pecos was so overrun with COVID patients that it stopped taking ambulance transfers from other hospitals. Things are better now, but it’s still hard.

“Nurses are burning out here, too,” says Auden Velasquez, a Fort Stockton family doctor who also does obstetrics. He says at times Pecos’s maternity ward has been down to four nurses, but it hasn’t gone on diversion. Recently, he says, McLaughlin, Big Bend’s ob-gyn, called with a transfer request for a patient in early labor who could probably have made the hour-long drive. But the delivery nurse on duty had been working twenty hours. “I said, ‘I don’t think it’s going to be safe to send her here,’ ” Velasquez says. “So I declined the transfer. McLaughlin understood. I assume she sent the patient somewhere else, but I don’t know where.”

In late July 2021, Big Bend was three weeks into its diversion plan when Jones, the stay-at-home mom, showed up to have her second baby. She was 36 weeks pregnant. “I walked into the hospital and was like, ‘I’m in labor.’ They’re like, ‘Labor and delivery is closed.’ I was like, ‘What? Is that legal?’ ”

Jones says she was sent to the ER, but because diversion had just started, the ER nurses didn’t know how to care for her. “I don’t want to throw anyone under a bus,” she says, “but they didn’t know how to check a cervix or how to monitor contractions. I was terrified.”

Jones says the ER nurses called McLaughlin for help. She checked out Jones and told her she was experiencing false labor, a precursor to the main event. Then McLaughlin explained that labor and delivery was only open Monday through Wednesday. The idea of driving an hour or more to an unfamiliar hospital scared Jones; she and McLaughlin decided to schedule an induction to ensure that she’d be able to deliver the baby in Alpine. “I didn’t want to be induced. I wanted my body to be able to just do its thing,” she says. “But I didn’t have a choice.”

Ray estimates that she induces a third of her patients to give them some control over when and where they give birth. But inductions can take a long time—multiple days for a first-time mother—so to ensure there’s enough time, the hospital will let her schedule them only on Mondays.

Induction isn’t a fail-safe plan, either. Unless there’s a medical necessity, doctors don’t do it before 39 weeks. There’s also a greater chance that after childbirth, a woman’s uterus won’t properly contract, and she could hemorrhage. For these reasons, many women prefer to go into labor on their own.

“I don’t want an induction. If the hospital is closed when I’m in labor, I’m just going to do it at home,” says Cheri Easter, a stay-at-home mom who’s pregnant with her second child, a boy. Easter lives so close to Alpine’s hospital that she can walk there. Still, she says, a home birth worries her: “I needed stitches the first time. My son is going to need a circumcision. There aren’t doulas or midwives here. I don’t know anyone in Alpine who’s had a home birth. Plus, all the aftercare? I won’t get any of that. It’s scary.”

At least Easter lives in Alpine. In Presidio, women are at even more of a loss. “If my water breaks, if I go into labor, I have to drive for three to four hours to get to another hospital,” says Brittany Alonzo, who’s about six months pregnant. “What if something happens? I think about it a lot. I don’t know what to do.”

Women do come up with contingency plans, but those don’t always work out. Manuela Avila, a dentist who works at Billings’s Presidio clinic, arranged to stay with family in El Paso as she neared her April due date, then give birth there. But she went into labor a month early. She and her husband made the four-hour drive to El Paso in the middle of the night. “Luckily my contractions hadn’t started yet,” she says. “That would’ve been a really long drive to be in pain for that long.”

Presidio has two ambulances but only enough medics to staff one. When Big Bend first went on diversion, Presidio’s emergency medical services tried taking women to Fort Stockton, a five-hour round trip. But having the ambulance gone that long was a problem. Too often patients suffering heart attacks and strokes were left stranded. Now it will drive only as far as Alpine to drop off a woman, even if she’s in labor and the hospital’s maternity ward is closed.

Troy Sparks, the director of Presidio’s EMS service, says he tries to speed up things for women by calling a medevac flight to meet them in Alpine and fly the rest of the way to Fort Stockton, but the planes aren’t always free. “I’d say 75 percent of the time they tell me they can’t come,” he says. As a result, EMS has delivered several babies in the ambulance. He knows of at least one who was born in a helicopter.

Further complicating things for Sparks is that Mexican women sometimes cross the border while in labor so they can give birth at a U.S. hospital. He and the doctors say they’re not necessarily doing so to ensure their children are U.S. citizens—the mothers return to Mexico after giving birth—but because the villages they come from don’t have hospitals either. They try to make it to Presidio or an even smaller border town called Candelaria and then rely on the ambulance to take them to Alpine. Most of the time, these women have had no prenatal care. So when they show up unannounced at Big Bend, doctors don’t know how far along they are or if their fetuses are healthy. In June, Sparks says, a woman crossed the border 37 weeks pregnant, was chased on foot by the Border Patrol, then tripped and fell and suffered a placental abruption, which is when the placenta detaches from the womb. Presidio’s EMS team raced her to Alpine, which was on diversion at the time but called in doctors and nurses to perform an emergency C-section. “They were down to minutes before they lost the baby and the mom,” Sparks says. “They did it. But it was close.”

Alpine’s hospital has been on diversion for more than a year now. No one expected it to last this long. Flores, Big Bend’s CEO, estimates they’ve turned away about fourteen women in labor. The rest have been too far along and delivered in the ER.

Sometimes things aren’t so bad. Last fall the hospital appealed to the government for help and got enough nurses from the Federal Emergency Management Agency to reopen labor and delivery full time. But they stuck around for only two months. When the nurses left, the unit went back on diversion. Recently the hospital hired a new sonographer so it can offer more prenatal appointments. At least two new labor and delivery nurses have also joined. One has no obstetrics experience, however, and will undergo two weeks of training. The ward intends to open full time by August 22, Flores said.

Flores is trying to establish recruiting partnerships with nursing schools across the state, and he’s had some success. In October, Billings testified before the Texas legislature about Alpine’s health-care problems; afterward, the state allocated $4 million for a program at the University of Texas at Arlington that’s intended to drive more nurses into rural health care. Of course, neither of these solutions will help staff the hospital today.

Big Bend once enjoyed a healthy number of privately insured patients (mostly Border Patrol families) who helped balance what it lost from treating women on Medicaid and the uninsured. But now some of those privately insured patients, who tend to be middle class, have started to schedule even their prenatal appointments elsewhere. If enough of them leave, it will be harder for the hospital to make money.

Even if Big Bend hires enough nurses to reopen its maternity ward full time, pregnant women in West Texas may still have trouble finding care. At the end of July, Billings quit practicing medicine to become an associate dean at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center in Odessa, where he’ll work to bring more health-care workers to rural areas. Alpine’s biggest problem, he says, is that it needs more people—more doctors and nurses, yes, but also dentists, lab technicians, and health professionals of all kinds. “So many of my patients are Spanish-speaking only. They need an advocate,” he says. “I’m the one in the white coat with a medical MD behind my name. I can open doors that maybe they can’t.”

The Rays are leaving, too. Working in such an intense environment has taken a toll. They have three young kids and need a change. Next spring they’ll move to New Zealand, which allows U.S. doctors to practice without having to get relicensed. Billings recently interviewed a doctor he hopes will replace him at the clinic. “But just one. We need more,” he says. “It’s hard to find candidates, plural, to come here.” The doctor hasn’t accepted the job yet; if she declines, only McLaughlin and Luecke will be left. They’re both in their sixties. Luecke broke his pelvis a few years ago and recently had a knee replacement. They have only so many years of work left in them.

It’s hard to say how all this will affect maternal health in Texas on an aggregate level. Unlike many states, Texas doesn’t regularly publish a statewide maternal mortality rate. (The most recent figure, from 2018, was slightly higher than the national average at the time.) It has a Maternal Mortality & Morbidity Review Committee, however, which in 2020 estimated that about 89 percent of childbirth-related deaths were from causes that could’ve been prevented if patients had better health-care access. The state did recently opt into a part of the American Rescue Plan, one of the many federal COVID relief bills, that provided funding to help expand states’ postpartum Medicaid coverage. Now, instead of losing Medicaid eight weeks after giving birth, Texas women can keep it for up to six months. That should help. Beyond that, there isn’t much else.

The U.S. won’t have a clear picture of how the pandemic has affected maternal health on a national level until the CDC releases its 2021 figures next year. The consequences of new abortion restrictions won’t show up for even longer. Billings and his fellow doctors say that since an abortion was hard to obtain in West Texas, they don’t expect an increase in births. Nor will they stop treating ectopic pregnancies or miscarriages, threats of prison time or no. But what they’re worried about is access to contraception. “Will there be legal challenges to offering contraception through programs like Medicaid?” Billings wonders. “There’s a genuine fear among patients and clinicians. It’s a potential target.” What used to sound far-fetched, he says, is no longer unimaginable. The future of maternal health care in the U.S. is already taking shape.

To be clear, no one who gave birth at Big Bend—or who was sent to another hospital—has died during diversion. There’s a reason the maternal mortality rate is measured per 100,000 births. These days, thanks to antibiotics, emergency C-sections, and sterilized equipment, most women and their babies survive. But there were close calls that made doctors nervous. Not long ago, one of Ray’s patients started bleeding to death six hours after giving birth. “Luckily, we were open. She was still at the hospital,” Ray says. “But if she’d been sent home, I don’t know.”

It’s the “what ifs” that keep her and the other doctors up at night. Will the new travel nurses know how to keep a premature baby breathing until the medevac gets there? When the unit is closed, will women make it to another hospital in time? Every delivery feels like a roll of the dice.

Ray says she recently had the hospital divert one of her patients to Fort Stockton against her advice. (Flores declined to comment on this.) The woman was having her fifth child and would probably give birth too quickly to make the hour-long drive. “I’m like, ‘I’m the doctor? And I say I’m not comfortable with this.’ And they’re like, ‘Too bad.’ They transferred her,” Ray says. “She made it. Barely. But that was literally just luck.”