In 2016 Chad and Jennifer Brackeen, a white, evangelical couple from Fort Worth, began fostering a Navajo and Cherokee boy. After they petitioned to adopt him the following year, a judge in Texas ruled that the boy should be sent to New Mexico to live with a Navajo family, following the provisions of the Indian Child Welfare Act, a 1978 federal law that requires that judges give preference to placing Native children with their tribes before looking to non-Native families.

The Brackeens were crushed. “How do we explain that to him?” Chad Brackeen told the New York Times in 2019. “He had already been taken from his first home, and now it would happen again? And the only explanation is that we don’t have the right color of skin?”

The Brackeens appealed the decision, and the Navajo family backed out of the adoption, so the boy never left the family before the Brackeens adopted him in 2018. But the couple felt that “we won our son in a technicality,” as Jennifer Brackeen wrote in a now-defunct blog, and that the law, which “is destroying the hearts of children across the country every day,” should be changed.

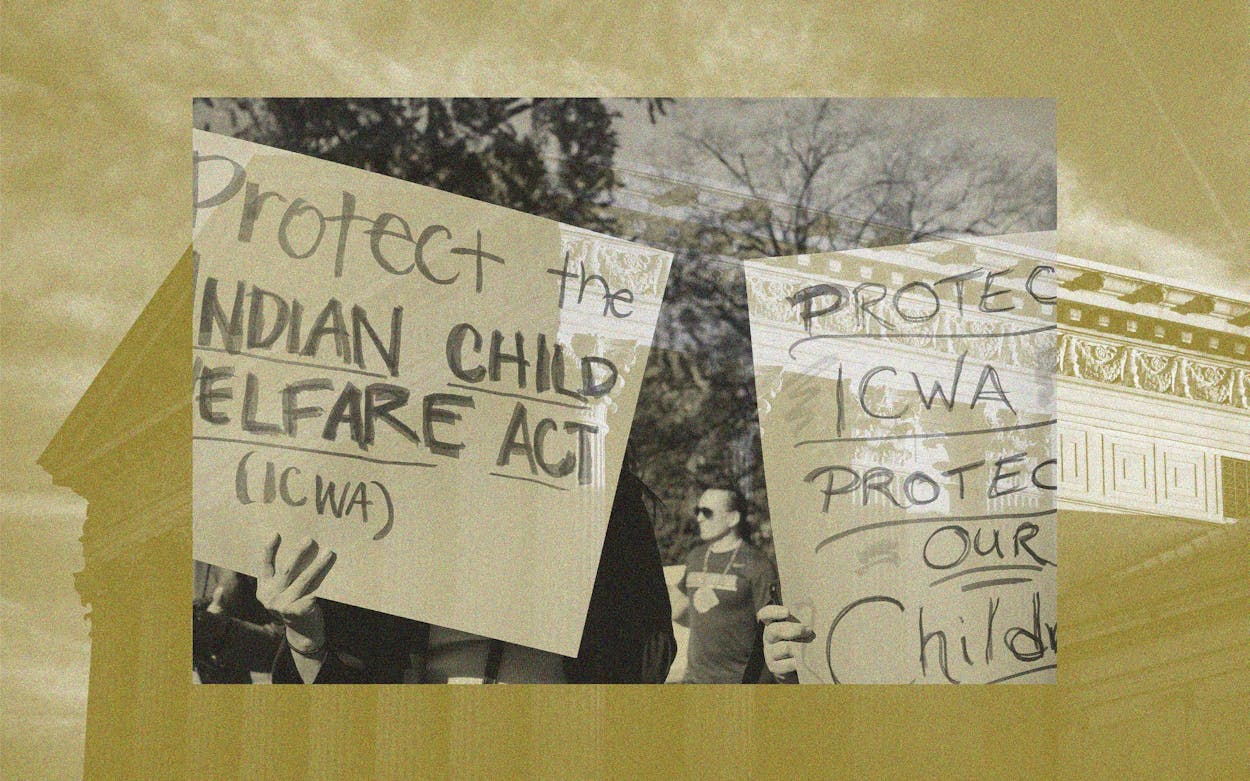

Their case spiraled into a Supreme Court case joined by Texas and two other states in an attempt to dismantle protections for Native families in the child welfare system. A sweeping 2018 ruling by Fort Worth–based U.S. district judge Reed O’Connor struck down the law and, in doing so, threatened the very concept of tribal sovereignty. In the following years, two decisions by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed much of O’Connor’s decision but struck down certain provisions of the law. The case, which has represented the most formidable challenge to ICWA since its inception, in 1978, has finally ended. On Thursday the Supreme Court ruled 7–2 to uphold the Indian Child Welfare Act in its entirety.

Tribes across the country argue ICWA is a vital law that halts the systematic destruction of their people. “A very basic act of sovereignty is the ability under law for tribes to protect their children,” said Chuck Hoskin Jr., the principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, which joined the lawsuit in defense of ICWA.

“The Indian Child Welfare Act did not emerge from a vacuum,” Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote in his concurring opinion. “It came as a direct response to the mass removal of Indian children from their families during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s by state officials and private parties.”

Indeed, the forcible removal of Native children from their families began much earlier, with the internment of Native children in Indian boarding schools across America, a practice that began in the late 1800s and continued through the middle of the twentieth century. In these schools children were forced to shed their customs and languages and were routinely abused. Many died: unmarked graves of Native children—at least one of them a mass grave—have since been found at the sites of residential schools in the U.S. and Canada.

As the residential schools began to close, the U.S. government pushed the Indian Adoption Project, which promoted adoption of Native children to white homes. “One little, two little, three little Indians—and 206 more—are brightening the homes and lives of 172 American families, mostly non-Indians, who have taken the Indian waifs as their own,” one 1966 Bureau of Indian Affairs press release declared.

In the late 1960s, a New York attorney named Bert Hirsch was sent to North Dakota on behalf of the Association on American Indian Affairs to represent a woman from the Spirit Lake Tribe in a battle for custody of her grandchild. Hirsch fought successfully in that case, but the experience made him aware of the widespread removal of Native children from their homes—not just in North Dakota, but around the country.

Hirsch and his colleagues began a study of tribes across the country to gauge the prevalence of courts breaking up Native families, and in 1976 they found that between 25 and 35 percent of all Native children were being removed from their homes. Nearly all of those children ended up with non-Native families or in institutions. As Hirsch worked on behalf of Native families, he said that in courtrooms it often seemed that “if you’re poor and you’re Indian, you lose your kid.”

Hirsch’s study was instrumental in passing ICWA in 1978. The law states that child welfare officials must make “active efforts”—a step above the widespread standard of “reasonable efforts” taken in most child welfare cases—to reunite Native children with their parents. If reunification isn’t possible, preference must be given for placing the child with their family, then their tribe, then even another tribe, before a child can be placed in a non-Native home.

The stipulations of ICWA are not absolute—as in the Brackeen situation, many Native children do go to non-Native homes. But the law gives tribes a seat at the table in court, and even the option to transfer cases involving Native children to tribal courts, with the aim of ensuring tribes have a say in what happens to their children.

One such Native child was Manilan Houle, who grew up in Duluth, Minnesota, and is a member of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. Now an adult, Houle says his tribe was involved in each stage of decision-making while he was in foster care. Houle ended up with a permanent family that is not Native. “I think a lot of people have this misconception that ICWA means that Native children can only be placed in Native homes or that it’s discriminatory, or racist,” Houle said. “ICWA gives tribes and tribal governments the ability to wrap their arms around the children who need their communities the most. I credit ICWA for me being able to find that forever family of people who supported me, even though they weren’t Native.”

Texas is home to hundreds of thousands of Native people, including three federally recognized tribes as well as members of other tribes. In 2021, according to federal data, only 38 non-Hispanic Native children were in the state’s foster care system. Still, even with such a small number of Native children in the system, Texas entered the Brackeen suit as a party to the case, arguing in part that it bore an undue financial burden by being required to fulfill the provisions of ICWA. Texas also argued that in some of the provisions of ICWA, the federal government overstepped its authority to direct state officials’ actions in child welfare proceedings, which take place in state courts.

In other states, even with ICWA in place, Native families continue to be disproportionately impacted by the child welfare system—in South Dakota, where Native children make up 12 percent of the population, they make up nearly 60 percent of the state’s foster children. Sarah Kastelic, the executive director of the National Indian Child Welfare Association, said that removals of Native children from their homes and communities, spanning generations, are still felt today.

“I’ve never been in front of a tribal council to talk to them about this work without several people raising their hands to talk about their personal story, to talk about people in their own family who’ve gone missing,” Kastelic said. “Children who were adopted out, children who were taken and nobody knows where they are. Cousins, aunties, people who are lost and families still grieve for them. People know who their missing relatives are. They’re supposed to be part of the fabric of their family and community, but there’s a gaping hole where those people should be.”

In 2018 U.S. district judge Reed O’Connor, of the Northern District of Texas, ruled on Brackeen, striking down ICWA on a wide variety of grounds that sent shock waves through tribal nations and among lawyers who practice federal tribal law. O’Connor ruled that ICWA was a “race-based” law, and therefore must meet the very high legal standard of strict scrutiny, which he ruled ICWA failed to meet. His ruling threatened to upend more than a hundred years of legal precedent that made clear that tribal nations are sovereign and therefore have a political, not a racial, relationship to the federal government.

Texas attorney general Ken Paxton praised the district court ruling, saying in 2018 that it “protects the best interest of Texas children. ICWA coerces state agencies and courts to carry out unconstitutional and illegal federal policy, and decide custody based on race.”

Thursday’s Supreme Court opinion, authored by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, sidesteps the race question, ruling that the individual and state plaintiffs lack standing on the issue. The ruling is particularly clear that Texas lacks standing to bring equal protection claims on behalf of its citizens, saying “the State’s creative arguments” fail to show why the state itself is an injured party.

Some ICWA advocates say that state child welfare systems are set up under the premise that middle-class white families are the standard to which other families are held. The child welfare system disproportionately impacts poor, marginalized communities, and recent changes in Texas laws acknowledge that poverty can often be confused with neglect. Kevin Noble Maillard, a professor at Syracuse University specializing in family law and adoption law and a member of the Seminole Nation, said Native families often feel bias against Native parenting practices, like communal parenting, in the courts. “The adoptive parents have long claimed this case as a racial issue, but what they have not recognized is their own racialized insistence on the neutrality of white parenthood,” Maillard said. “They tried to fight sovereignty with dog whistle animus, and they lost.”

The Supreme Court took on another legal argument made in Brackeen. O’Connor ruled in 2018 that Congress overstepped its power by enacting ICWA because parent-child suits are litigated in state, not federal, courts. Tribes feared that a Supreme Court ruling finding that Congress did not have the power to enact ICWA could decimate a wide swath of laws that govern federal Indian policy. “If the Supreme Court upheld Judge O’Connor’s thinking that the Congress had no power to enact this law to begin with, that could be the beginning of the end of Indian tribes,” Hirsch said by phone after the ruling. “And that was the great fear of going into this.”

But Barrett, on behalf of the majority, makes clear that Congress was well within its authority to pass ICWA, writing that “if there are arguments that ICWA exceeds Congress’s authority . . . petitioners do not make them here.”

Two justices, Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, dissented. “Whatever authority Congress possesses in the area of Indian affairs, it does not have the power to sacrifice the best interests of vulnerable children to promote the interests of tribes in maintaining membership,” Alito wrote in his dissent.

But in his strongly worded concurring opinion, Gorsuch underlined the long history of Native family separation enacted by the government and called the practice of removing Native children from their homes “an existential threat to the continued vitality of Tribes.”

“In adopting the Indian Child Welfare Act,” Gorsuch wrote, “Congress exercised that lawful authority to secure the right of Indian parents to raise their families as they please; the right of Indian children to grow in their culture; and the right of Indian communities to resist fading into the twilight of history. All of that is in keeping with the Constitution’s original design.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Supreme Court