As a general principle, voters should not be held personally responsible for the shortcomings of the men and women they elect to office. If we were to hold them to that standard, though, the constituents of House District Two, covering three counties between Dallas and Tyler, would owe us all a big apology—maybe an edible arrangement or two. The man they sent to Austin in 2020 and 2022, Bryan Slaton, was a walking plague. Ultimately, he was fatal only to himself. The Republican from Royse City became the first member of the House to be ejected from office since 1927, by a 147–0 vote, after he plied a nineteen-year-old staffer with alcohol and had sex with her.

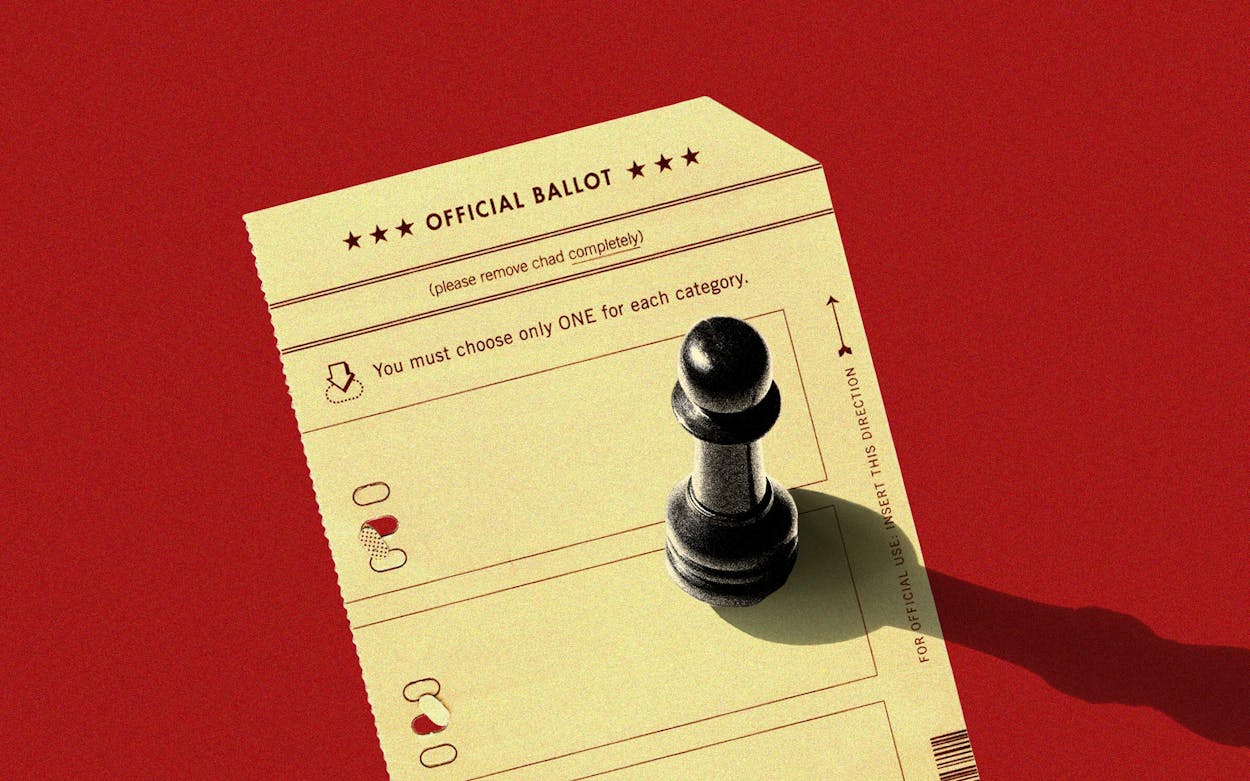

One reason it would be wrong to place blame on the good voters of the second district, though, is that while they may have elected Slaton, he was selected for that election by a powerful coalition of moneyed interests. And those interests are back. On Tuesday, Slaton’s successor will be confirmed in a special election. The two-way runoff features Brent Money, a candidate with similar politics to Slaton’s and supported by the same coalition of backers in the right wing of the party, and Jill Dutton, supported by a rival coalition of backers allied with the more moderate House leadership.

Brent’s last name feels on the nose. A real estate and probate lawyer and a former charter school board member, he is supported by some of the richest men in Texas. Brothers Dan and Farris Wilks, both West Texas oilmen, gifted him $50,000 in January alone through their new front group, Texans United for a Conservative Majority. Defend Texas Liberty, a right-wing political action committee largely funded by billionaire Christian nationalist Tim Dunn, previously pitched in $35,000. Dutton, who runs a small construction-lending consulting business alongside her husband, is also supported by some of the richest men in Texas, netting $50,000 checks from both John Nau III, a beer distributor and prolific campaign donor, and the organization he helps fund, Texans for Lawsuit Reform. In just the first twenty days of January, Dutton reported more than $286,000 in donations, while Money reported $110,000.

Amid this flurry of cash, the runoff campaign has had seemingly little to do with the needs of the district’s voters. It’s a proxy war between very powerful figures, which is one reason the race has garnered so much attention. The culture warriors of the GOP’s right wing and the more business-focused TLR are warring as much out of habit as because of real doctrinal differences. The most important question at stake is, perhaps, how each candidate will relate to the leadership of the House, which is not a matter most voters care very much about.

That’s not to say there’s no meaningful difference between the two candidates. While they’re mostly similar in their policy preferences, that they’ll come to the House with different friends is an important distinction. Dutton is a former school board member who touts her commitment to public education. She has been endorsed by House Speaker Dade Phelan’s allies and by former governor Rick Perry. Money, meanwhile, is a vocal supporter of school vouchers who is endorsed by every right-wing grandee you can think of, from U.S. senator Ted Cruz to Texas attorney general Ken Paxton (whose impeachment Money opposed, while Dutton has said she “respect[ed] the process.”) Slaton’s former buddies in the House, including the right-wing Steve Toth, a minister from The Woodlands, and Nate Schatzline, a former youth pastor from Fort Worth, are also backing Money, as is Governor Greg Abbott, who doesn’t always join the gang.

At a January 18 debate in Sulphur Springs, eighty miles northeast of downtown Dallas, the major political difference between the two became more apparent. Dutton is polite and soft-spoken. She read her opening remarks from a sheet of paper. Her kids have been educated through a mix of private and public institutions and homeschooling, she said, but it was in the district’s public schools that they got the best instruction. “Our rural public schools are the cornerstone of our communities,” she said, as well as some of their top employers.

Money is slicker. Throughout his remarks, he offered conditional support for public schools. It was a mistake for the Legislature to tie teacher pay raises to a voucher program last year, he said. But decades ago, he taught in a public school for two years, and it soured him, as it did so many young idealists who joined Teach for America shortly after college. He launched into a disquisition on what the sheriff of El Paso in No Country for Old Men called “the dismal tide.” When he was teaching twenty years ago, Money said, older teachers would moan about how the kids weren’t like they used to be. “My thought at the time was, kids are the same as they always are. Their parents are getting worse,” he said. “Well, fast forward twenty years, and those students that I was teaching have students that age, the ones that weren’t getting parented well. Now we’re another generation into it.” Signs and wonders. “I’m shocked and heartbroken at some of the stories,” Money said. “Our system is broken.”

Given Money’s estimation that the world is going to hell in a handbasket and parents are responsible, the next turn he took at the debate was surprising. He said the best form of accountability “is parents who have a choice,” which would be achieved by “breaking up the government monopoly” over education. He never really closed the loop on this line of argument; he didn’t need to. His support of school vouchers is the reason he has the backing of the governor and so many other rich men.

But in the context of this election, the embrace of private schools is a little strange. House District Two consists of three counties: Hopkins, Hunt, and Van Zandt. According to the database administered by the Texas Private School Accreditation Commission, there are no accredited private schools in Hopkins and Van Zandt Counties, home to about 37,000 and 60,000 residents, respectively. Hunt County, population 100,000, is home to just one accredited private academy, Greenville Christian School, with a total PK–12 enrollment of 303 students.

If Money and his benefactors succeed in breaking the “government monopoly” on education, as he calls it, it would benefit his constituents very little (unless his voters are prepared to drive their kids to the Dallas suburbs or Tyler every morning). And yet Money’s backers argue that vouchers are the most important issue facing the Legislature. In January, Cruz came to speak at a Money rally, drawing a crowd of several hundred. The senator put on his best down-home-country-boy accent and purred to the crowd that it was “great to be with you at a time when the whole country is so messed up.” He was there, he said, because it embarrassed him so much that so many other states had adopted voucher schemes when Texas had not.

At the rally, conservative activists could take pictures of themselves with cardboard silhouettes of all the fancy folks who had endorsed Money—the kind where you stick your head through a hole. The stand allowed warriors for the cause the remarkable chance to appear alongside notables including Abbott and Cruz; the indomitable Ken and Angela Paxton; big-hatted agriculture commissioner Sid Miller; right-wing state legislators Bob Hall, Brian Harrison, Mayes Middleton, Schatzline, and Toth; and aging GOP-friendly rocker and hog-hunting enthusiast Ted Nugent. The stand was supposed to suggest that Money was in good company and had powerful friends. But it suggested something else: that Money was the cutout, that his personal features were unimportant, and that he was in the running because wealthy and influential people wanted him to be.

In this race, the very idea of “local politics” is dead. When a local TV interviewer asked Money to name the two most important issues in the campaign, he responded “border security and border security.” You’d never guess that his would-be district is closer to Kansas City than Brownsville.

Part of the reason Abbott and friends are investing so much time and effort in this race is that they want to champion it as a bellwether for the rest of the primary season, in which early voting begins in late February. The dates for this special election in House District Two were set by the governor, who will doubtless champion Money’s election if it advances his plan to win a voucher program in the Eighty-ninth Legislature, after multiple setbacks in 2023. Skepticism is warranted, though, on whether this election is really a preview. If Money wins, one right-wing lawmaker will have been replaced by another. The real test of Abbott’s plan, and everyone else’s, comes in March.