When Valentín Valdez heard that a shooter had opened fire at a local Walmart, he immediately thought of his students. Valdez, 29, teaches freshmen at a magnet high school in El Paso. “I am terrified that one of them got hurt,” he said, holding back tears outside a blood donation center Saturday evening. In just over a week, school would start—so now was the prime time to shop for supplies. Walmart and a mass shooting: it was back-to-school season in America.

A few minutes before 11 a.m. on Saturday, a 21-year-old from Plano wielding an assault rifle killed 23 people in the Walmart near Cielo Vista Mall in El Paso, injuring dozens of others. Law enforcement sources cited by NBC News said they are “reasonably confident” that the gunman had posted a racist, anti-immigrant manifesto online before the shooting.

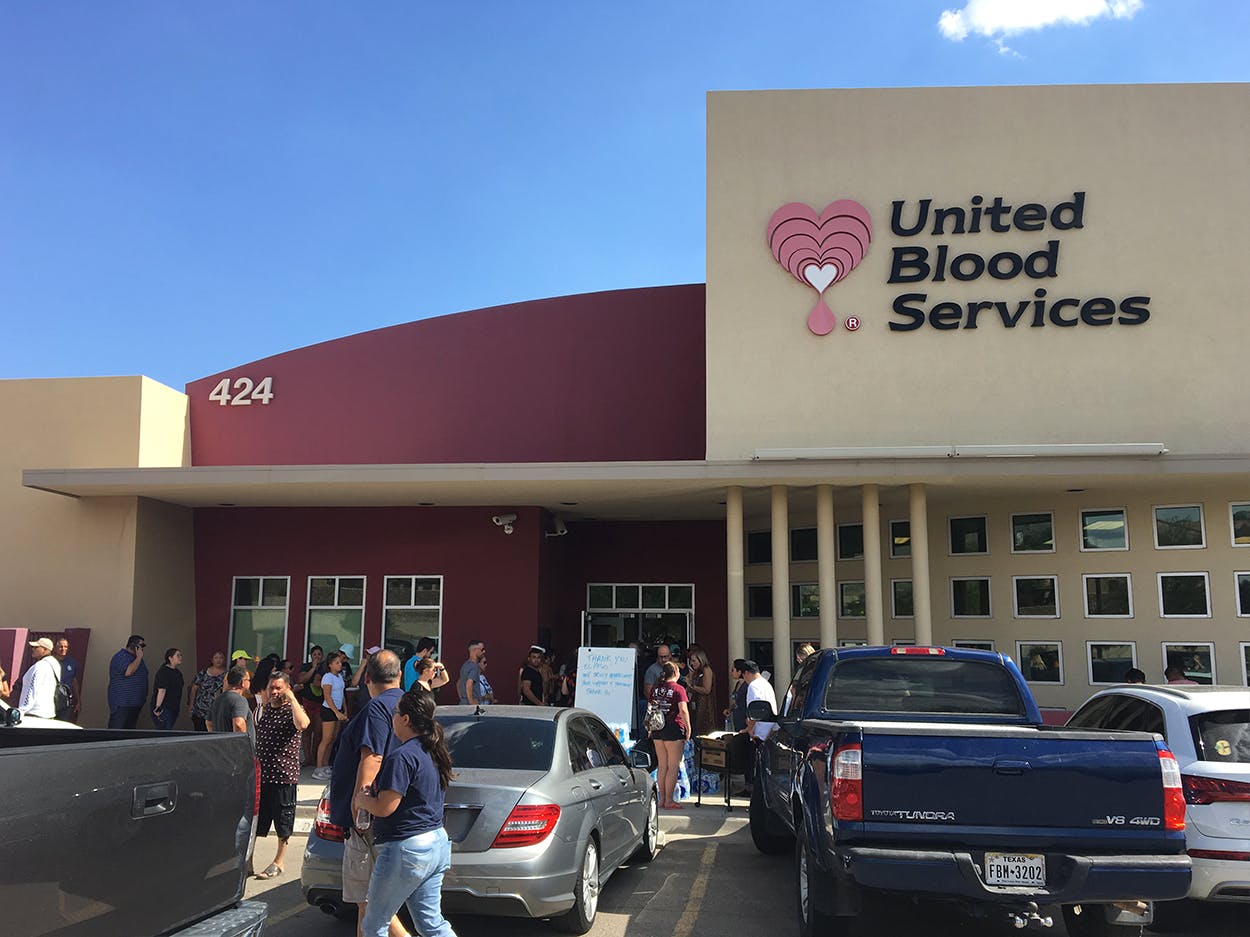

By early afternoon, crowds had formed at blood banks around the border city. Valdez joined an estimated four hundred people at a blood bank in west El Paso. The line snaked around the building, and the front room, where staffers interviewed donors and drew blood, was packed. Stockpiles of chips and water bottles grew as local business and church groups dropped off donations. Volunteers walked up and down the line, offering snacks and an occasional umbrella to shield from the sun. By late afternoon, blood bank staffers began to turn people away and schedule appointments for later in the week; the blood bank couldn’t process any more donors that day.

At the blood bank, a common refrain was “I have no words.” But when El Pasoans could find the language, they said they were proud of their hometown and dismayed that an outsider could wreak such havoc on their city—one of the safest in the country. “This is not our city,” Leticia Medrano, 55, said of the violence. “We are very open and very accepting of everyone.” Jonathan Barreras, 20, was playing Overwatch with friends when his mom came in to break the news. The group rushed to the blood bank and joined the line. Around 5 p.m., a volunteer told them to go home and come back the next day. But like many others who had been turned away, they decided to stay to book an appointment and show solidarity. “We stay together in hard times,” Barreras said. “Even though we’re different colors and races, we come here together.”

Aaliyah Montgomery, 22, was in the middle of an advanced skills training for EMTs when she heard what had happened. She wasn’t on call at the time, but her mind immediately went to the first responders. “Being in class, knowing you can help, it’s hard not being able to do anything,” she said, articulating a general feeling of helplessness that drove people to the blood banks.

Around 5:30 p.m., more than six hours after the first shot was fired, Valdez’s family joined him at the entrance to the blood bank. His father, Ruben Valdez, is an El Paso native whose own father grew up in Ciudad Juárez. Unlike his son, who said he didn’t want to politicize the tragedy, Ruben Valdez holds President Trump’s rhetoric about immigrants partially responsible for the violence. “It emboldens some people,” he said. “Now they have something bigger than themselves to fight for.” But he was hesitant to blame the polarized political climate and anti-immigrant sentiment wholly on the president. “I think it’s problematic to try to pin this on one person,” he said. “I think everyone participates in creating this kind of division. … We’re vilifying anyone whose opinion is not like ours. That’s what we as Americans, we as Texans, we as El Pasoans, we as humans have to try to avoid.”

“I’m not surprised it was someone from out of town,” Valentín Valdez cut in, echoing others who said an El Pasoan would never have committed such a crime. “I have never thought that someone who really is from here could be capable of this.” His mother, Christiane Herber-Valdez, who immigrated to the U.S. from Germany when she was fourteen, agreed. “That’s what’s frustrating to us. To hear that someone from outside of El Paso is coming and attacking our city.”

But remarkably, that faith in El Pasoans did not translate into distrust of others. Instead of warning outsiders away, Valentín Valdez extended an open invitation.

“Come, come, come,” he said. “But don’t come for a day. Come stay with me for a week, and I’ll show you around. Let me show you what El Paso is. Because El Paso is beautiful.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- El Paso