During a visit to Houston last week, vice president Kamala Harris delivered what was billed as a pitch intended to get Latino Texans excited about President Joe Biden’s reelection campaign. After taking the stage, Harris had to implore the cheering audience to settle down. Then she spoke for thirty minutes, expressing hope that—after a 29-year electoral drought—Democrats in Texas might earn some victories in statewide races. “We’ve got a lot of work to do to make true the promise of who we are as America,” she said. “We’re going to have to build [a] coalition, and we’re going to have to remember that . . . this is a time for us to recommit ourselves.” Hours later, at a fundraiser, Harris’s husband, Doug Emhoff, declared that “we will never give up on Texas.”

A good shepherd, according to the Gospels, will leave his flock to rescue the one sheep who has wandered astray. But what if that errant sheep has lost faith in its shepherd? Democrats in Texas have been hearing for years that the party is ready to compete in statewide races here, but after three decades of failure by the state and national parties, it’s getting ever harder to get the rank and file energized. In 2018, Democratic Senate nominee Beto O’Rourke came within 2.6 percentage points of defeating Republican incumbent Ted Cruz, but no statewide candidate has come nearly that close since. In 2020, after national Democrats poured money into Texas, no Democrat came within 5 percentage points of winning statewide office. The state party used its bolstered coffers to register gobs of new voters, yes, but the GOP got more of their new registrants to actually turn out.

Between last year’s primaries and midterms, markedly fewer Democrats registered to vote than had done so between 2018’s primary and midterm races. Republicans trounced their opponents up and down the ballot. And in 2023, Democrats seem to remain reluctant to head to the polls. In the greater Houston metro area, where Harris spoke, fewer than one fifth of registered voters cast votes in last month’s mayoral race, which, while technically nonpartisan, featured a slate composed entirely of Democrats. (The race now heads to a runoff between U.S. congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee and state senator John Whitmire.)

Despite these portents, one group of political gurus thinks Biden’s party would be wise to spend in Texas: Republican operatives. They note that the last presidential contest, in 2020, was the second-closest Texas race for the White House over the last quarter century, and the state is now within the margin where targeted investment of money and organizing muscle can make the difference in a statewide race. Steve Munisteri, the former chairman of the Republican Party of Texas and the leader of one of its main voter-registration efforts, noted that, all else being equal, the state favors Republicans by about five or six percentage points. “If Republicans don’t make a major effort and the Democrats are united and spend a whole bunch of money,” he said, “then, theoretically, Democrats could be competitive.”

Broad demographic factors have convinced Democrats for decades that they might turn Texas blue. Some of the state’s suburban counties, which are also some of the fastest-growing parts of the state, are becoming more solidly Democratic. And their leftward shift over the last decade has made Republican presidential contests much closer, particularly in the Trump era. In 2008, Republican presidential nominee John McCain won the state by roughly twelve percentage points; in 2020, former president Donald Trump won Texas by fewer than six percentage points. Democrats are unlikely to close the gap entirely in 2024, but some GOP political operatives think they could succeed, perhaps as soon as 2028 or 2032, if they make the right investments in money, organization, and candidate recruitment—and develop policy positions that attract swing voters without alienating the party’s base of more liberal urban voters.

“It took a hundred years for Republicans to eventually win in Texas,” said Derek Ryan, a data expert who maintained the Texas GOP’s voter file for two decades. He added that for Democrats, “it’s not going to take that long.” He said the key for the party is running “rock star” candidates who can energize both Latino and swing voters. The Democratic Party in Texas has long struggled to field both well-known and competitive candidates for statewide seats, but in downballot races where it has, the party has seen some success, Ryan noted. “We’ve seen at the local level that it’s possible to shift a county from red to blue in just a handful of election cycles,” he said. “So it’s entirely possible that things could change enough, statewide, over the next few election cycles to put Texas in play.”

Biden and Harris have not yet announced more trips to the state. Investing here comes with costs, and Biden will need to focus on at least four key swing states—Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, and Wisconsin. Texas doesn’t figure to be part of his path to victory. Still, other national Democratic-aligned groups are ready to drop cash in the state, to help both statewide candidates and those running for Congress. The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee is investing heavily in the Texas Senate race, where Colin Allred, a U.S. congressman from Dallas, and Roland Gutierrez, a state senator from San Antonio, are seeking the Democratic nomination to challenge Cruz, one of the most loathed senators in Washington, D.C. Meanwhile, one of the more competitive U.S. House races this cycle will be the battle to reclaim Texas’s Fifteenth Congressional District, a fajita-shaped polity that stretches from San Antonio down to the Rio Grande Valley and is currently represented by Republican Monica De La Cruz. In April, the U.S. House Democratic campaign arm announced that it would focus efforts on the district as part of the party’s larger plan to reclaim control of the lower chamber of Congress.

Unfortunately for Texas Democrats, they don’t have a quixotic, skateboarding, f-bomb-dropping candidate to rile up younger voters who might otherwise avoid the polls, which is where the need for heavy investment arises. “I would presume that [national Democrats] are going to invest heavily in the Senate race because, one, they said they would, and, two, they don’t have many other options,” Munisteri said. The Texas race offers the most promising pickup opportunity for Democrats, mostly because the national map looks otherwise bleak for the party: the recent retirement announcement of Democratic senator Joe Manchin, of West Virginia, means that if Democrats want to maintain control of the Senate, they might have to beat Cruz. “If you don’t have any better places to play, you’ve got to put your money someplace.”

A second issue for Democrats running statewide, though, is that in order to win, they have to earn the votes of voters who identify as conservative on various issues, such as immigration, oil and gas, and policing. On some of these issues, certain Democrats’ stances, such as support for the Green New Deal, put them out of sorts with the voting populace. On others, like policing, the GOP has successfully convinced many voters that Democrats favor more extreme positions than they do: in 2020, Joe Biden was painted as supporting “defunding the police,” a position not embraced by a majority of Texas voters, but also one that the then–presidential candidate disavowed.

Ultimately, any bet on Texas is one primarily for the future, not for 2024. It took decades for the party to build infrastructure and turnout operations in Arizona and Georgia, former GOP strongholds that both went blue in 2020. “People are always skeptical, but if you think about someplace like Georgia, somewhere along the line you hit the tipping point. To hit the tipping point, though, you have to keep putting water in the bucket. You have to keep investing,” said Carroll Robinson, a public administration professor at Texas Southern University who ran for chair of the Texas Democratic Party in 2022. When he ran for chair, one of Robinson’s major criticisms of the party was that it had not done the basic math to determine how many Democrats needed to turn out where to win. He thinks focused investment is starting to change that: Democrats now have better modeling that they can share with candidates. “Now there’s a different mindset about how we build an infrastructure in Texas to do voter engagement and turnout, and we’re educating candidates earlier,” he said.

Meanwhile, Democrats aren’t alone in making a significant investment in Texas. While Harris was in town, a group of Hispanic Republican lawmakers and candidates convened in Houston for a fundraiser at which they emphasized that issues affecting Latino voters are the same ones affecting most Americans. The fundraiser also brought in a whopping $250,000.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

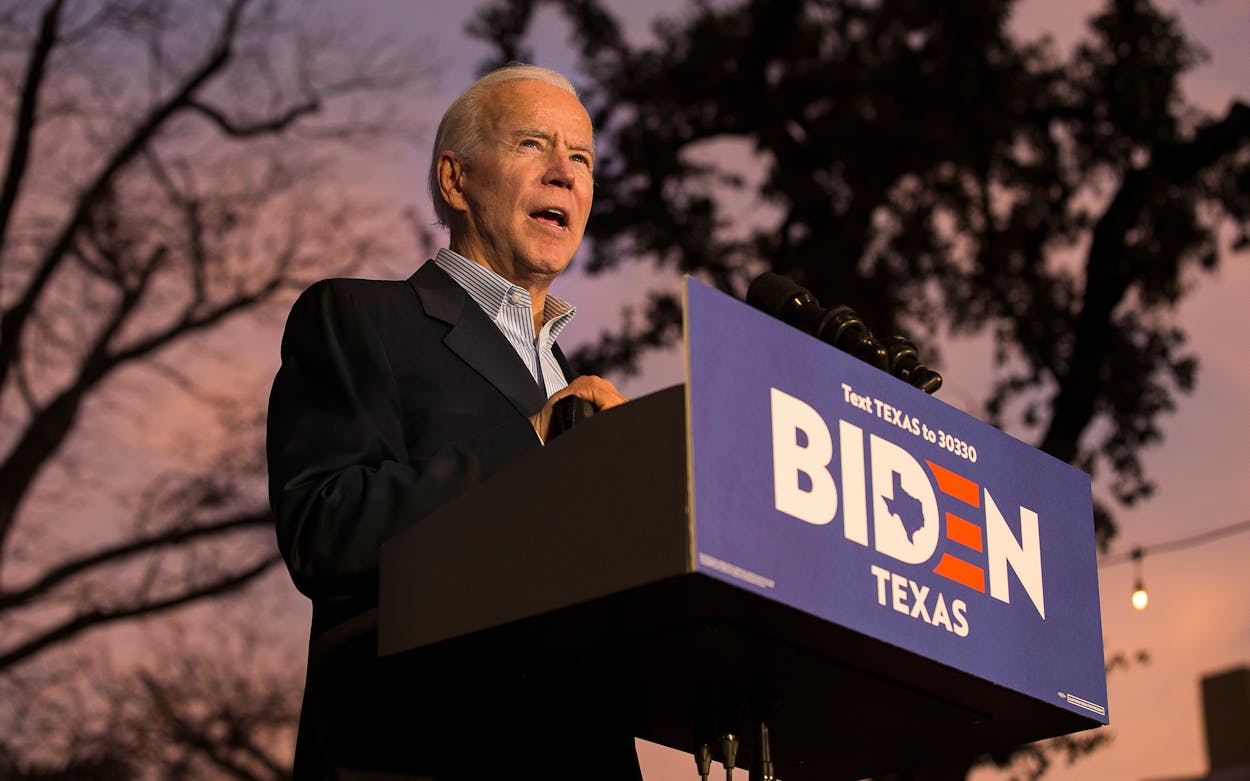

- Joe Biden

- Donald Trump