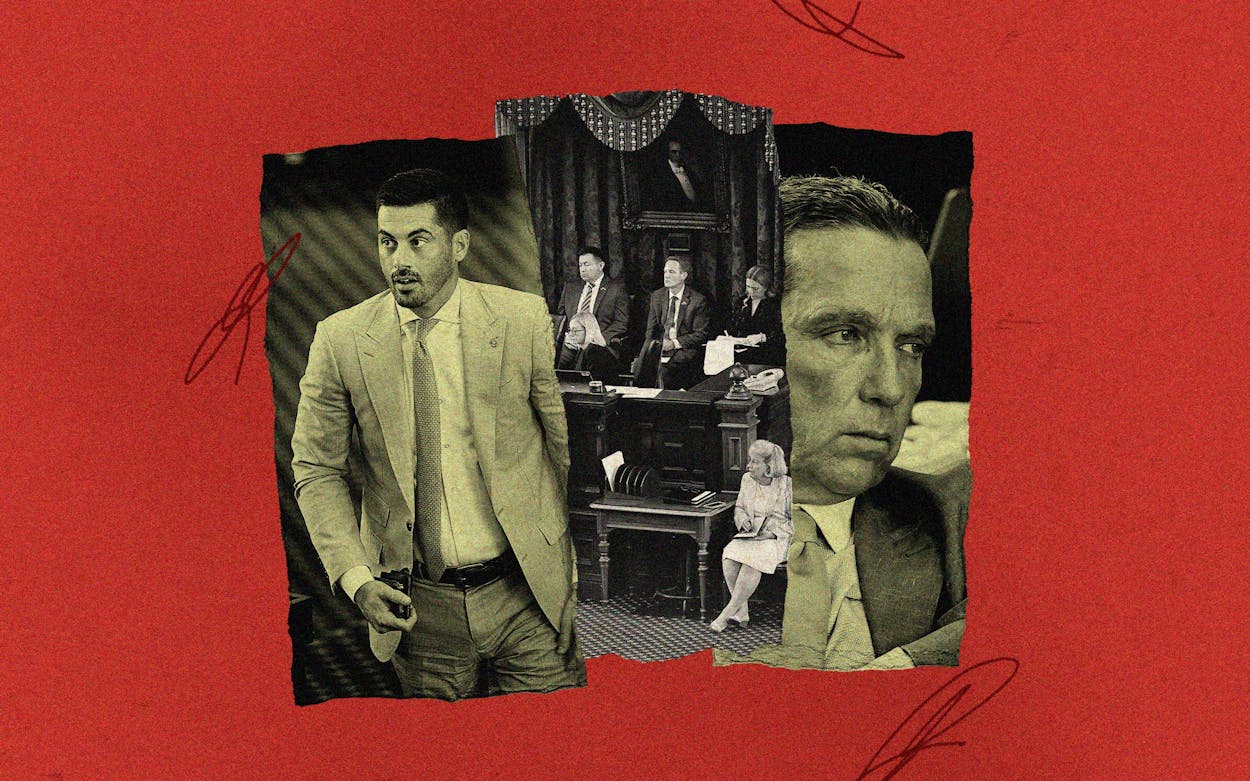

The story of Brandon Cammack—the unfortunate personal injury lawyer whose testimony dominated the sixth day of Ken Paxton’s impeachment trial—resembles one of eighteenth-century English artist William Hogarth’s moral allegories. Like “The Rake’s Progress,” a series of eight paintings depicting the debauchery and downfall of a profligate heir, Cammack’s is a cautionary tale. Call it “The Attorney’s Temptation.”

Cammack is central to the fifth article of impeachment, which accuses Paxton of engaging the Houston attorney “to conduct an investigation into a baseless complaint, during which Cammack issued more than 30 grand jury subpoenas, in an effort to benefit Nate Paul or Paul’s business entities.”

In September 2020, when this story began, Cammack was an ambitious 34-year-old Houston personal injury attorney, just five years out of law school. One day a fellow attorney named Michael Wynne, who knew Cammack through the Rotary Club and the Houston Bar Association, asked whether he might be interested in doing some work for the Texas attorney general. Next thing Cammack knew, he was summoned to Austin to meet the big man. In their initial interview Paxton was cagey about the details of the job, but he told Cammack it was something his senior staff refused to do.

For a more experienced lawyer, this might have been a red flag—the first of many. Not for Cammack, who said he was so proud of meeting Paxton that he called his grandmother on the drive home to share the good news. Soon Cammack had signed on as an outside counsel for the attorney general, making $300 an hour. He had nearly 75 cases on his personal-injury docket at the time but was willing to put his career on hold to help Paxton out. “I was excited to work on a project with the AG’s office,” he earnestly testified. “It’s the top law enforcement office in the state.”

Cammack began making regular trips to Austin to meet with Wynne’s client, real estate developer Nate Paul, who was being investigated by the FBI over alleged financial crimes. During their first meeting, Cammack testified, Wynne laid out his evidence for a wide-ranging conspiracy against Paul involving fraudulent search warrants, crooked Department of Public Safety officers, and corrupt bankruptcy judges. Several previous trial witnesses, including retired Texas Ranger David Maxwell, have testified that the evidence was laughable and the conspiracy absurd. But Cammack, bless his heart, believed Paul was onto something. “I was convinced by what I was shown,” he said when asked by prosecuting attorney Rusty Hardin. “I was like, if what he’s showing me about the search warrant being altered is true, this is a big deal.”

To investigate the conspiracy, Cammack would need to subpoena witnesses, including law enforcement officers, judges, and attorneys. This, too, did not deter him—an indication that Paxton had hired the right man. (“You need guts to do this kind of thing,” Cammack recalled Paxton telling him.) As a newcomer to the case, Cammack wasn’t sure where to begin. Fortunately, Wynne was happy to help out. He compiled a list of about forty people of interest, whom Cammack dutifully served with grand jury subpoenas. Wynne even tagged along with Cammack and helped him deliver subpoenas to two Austin-area banks that were trying to foreclose on Paul. (Under cross-examination, Cammack later denied that these actions were intended to benefit Paul’s businesses.) Cammack kept Paxton in the loop the whole time, communicating by encrypted email, encrypted text messages, and one of Paxton’s two cellphones.

On the stand, Cammack wanted the senators to know that he wasn’t totally oblivious. Before accepting the assignment, he said, he had called the State Bar Association’s ethics phone number and told them what Paxton was asking him to do. “They told me, ‘Congratulations on the job,’” he recalled. Still, as his investigation proceeded, Cammack couldn’t help but fall prey to doubt. He wondered why Paxton never gave him an official email address or business card. He wondered why his invoices were never paid. He wondered why Paxton wouldn’t share the Paul case file. However naively, he placed his trust in Paxton. Surely the Texas attorney general, the highest law enforcement official in the state, wouldn’t be involved in anything shady. (Some background reading on Paxton might have tempered Cammack’s certainty.)

Then everything came crashing down. Shortly after the subpoenas started flying, Cammack received a cease and desist letter from deputy attorney general Mark Penley. Then U.S. marshals showed up at Cammack’s Houston law office. When Cammack called Paxton in a panic, trying to figure out what was going on, the attorney general, he testified, advised him not to talk to the marshals without a lawyer. Then he received a second cease and desist letter from Jeff Mateer, Paxton’s top lieutenant. He said Paxton urged him to continue investigating, but Cammack was starting to freak out. “In my mind, I was like, I’ve gotten two cease and desist letters and I haven’t been paid,” Cammack recalled thinking. “I’m not doing any more work.”

The end came in late September, when Cammack was once again summoned to meet Paxton in Austin. This time, the meeting took place at a Starbucks, and included Cammack, Paxton, and Brent Webster, who had been appointed first assistant attorney general after Mateer’s resignation. It was Webster who informed Cammack that the contract he had signed was invalid and that he would not be paid for his work. “What about my $14,000 invoice?” Cammack recalled asking. “You’ll have to eat that invoice,” Webster allegedly replied, while Paxton listened in silence.

As the meeting ended, Paxton and Webster piled into their car for the ride back to the office—nearly leaving Cammack stranded at the Starbucks. “Paxton tried to drive off, but I told him I needed a ride back to my car,” Cammack testified this afternoon.

“So they brought you there, terminated your contract, and would have left you in the street?” prosecuting attorney Rusty Hardin asked in disbelief.

“Felt like it,” Cammack replied.

For his cross-examination, defense attorney Dan Cogdell drilled down on the fifth article of impeachment. Under Cogdell’s questioning, Cammack acknowledged that he didn’t consider Paul’s complaint baseless and that the grand jury subpoenas were not intended to benefit Paul or Paul’s business entities.

Was the Houston attorney simply a patsy, the unwitting cat’s paw of Paxton and Paul? We may never know. Based on his testimony today, it seems unlikely that Cammack will ever again give someone the blind loyalty he showed Paxton. As he rose from the witness stand late this afternoon and walked out of the Senate chamber, the words of a different eighteenth-century Englishman came to mind:

He went like one that hath been stunned

And is of sense forlorn:

A sadder and a wiser man,

He rose the morrow morn.

Here’s what else you need to know:

- Cammack wasn’t the only lawyer whom Paxton considered for the job of outside counsel. The next witness the prosecution called was Joe Brown, a former U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Texas. Brown testified that he was approached by Paxton’s team but became concerned about a conflict of interest, given that one of the entities listed in Paul’s complaint was the Texas State Securities Board, which had previously fined Paxton. Ultimately Paxton hired the young Houston attorney instead.

- Former deputy attorney general Darren McCarty, one of the eight whistleblowers, was the final witness of the day. He testified about his involvement with the AG’s intervention into Paul’s legal dispute with the Mitte Foundation, a nonprofit, over its investment in his businesses. “I believe that [the attorney general’s office] had been turned over by General Paxton to a private citizen to do his bidding,” he said. “It was acting against the interest of the State of Texas.”

- Early this morning a photo of Senator Angela Paxton staring at her wedding ring went viral on social media.

- Defense attorneys appeared concerned about managing their 24-hour time allotment, with Tony Buzbee repeatedly reminding witnesses to “keep it short.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Ken Paxton