In late March, the sun smoldered on the onion fields outside the city of Edinburg, less than twenty miles north of the United States–Mexico border. Dozens of migrant workers and their families partook in the annual harvest—el rebote de la cebolla, as they call it. Some were teens participating for the first time; others, in their late sixties, struggled to keep up with the pace of their more vigorous counterparts. A few supervisors in the field had legal residency status, but most of those picking onions were undocumented.

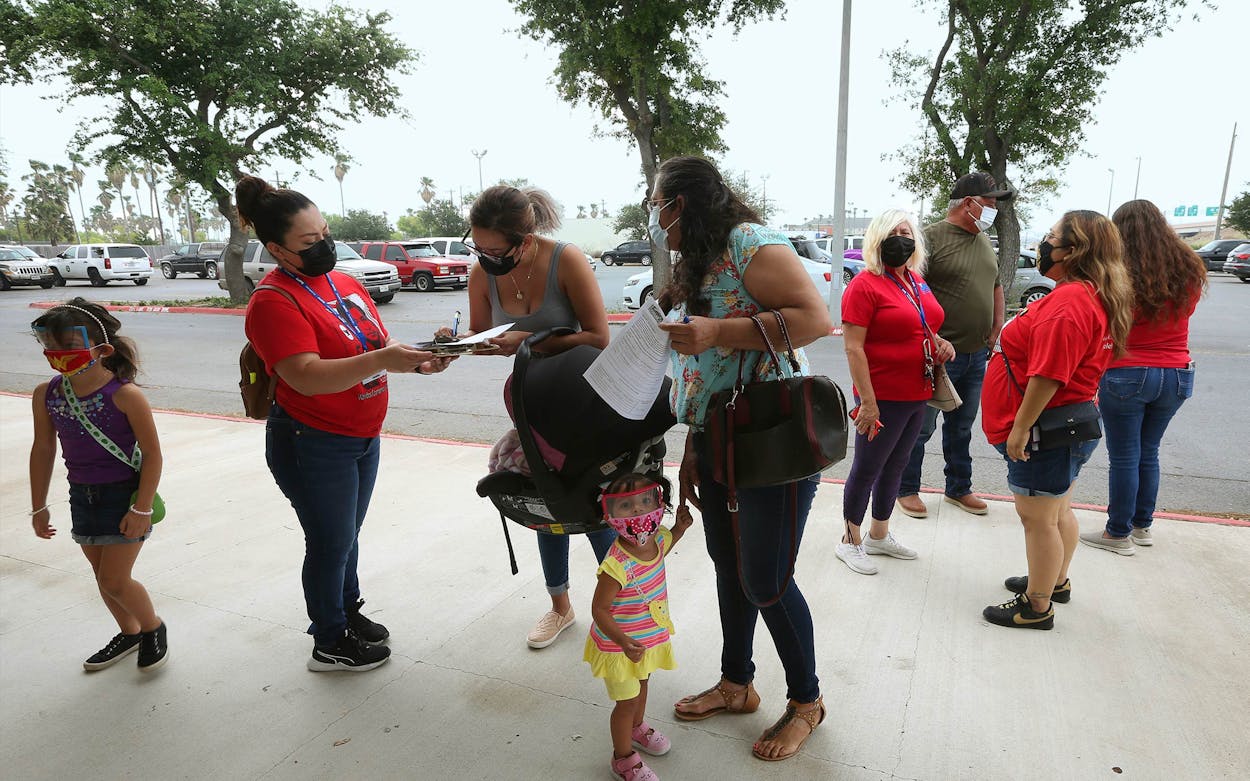

Elizabeth Rodriguez, an organizer for La Union del Pueblo Entero, a community group working closely with the Rio Grande Valley’s immigrant population, arrived at one onion field that morning to approach workers and help them register for COVID-19 vaccination appointments. Many of the migrants were surprised but grateful to have her help. A few, however, were distrustful. One man, sitting on top of a bucket and chopping onions as his family picked them, rejected Rodriguez’s offer to set up appointments for him and his children. “I don’t want the chip in my body,” he told her, referencing a conspiracy theory that the vaccine would be used to track the location of those who get the shot.

Experts with the Department of Homeland Security and National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine have long cautioned that for the nation to successfully reach herd immunity, all Americans, regardless of immigration status, must be vaccinated. To that end, the Biden administration announced plans to offer vaccination to all U.S. residents, including undocumented ones. But in South Texas and Edinburg’s Hidalgo County, where it’s estimated that more than 10 percent of the population is undocumented, some migrants faced procedural barriers to getting the vaccine through February. Now that those have lifted, LUPE still estimates about 25 percent of its clients have rejected the vaccine—fearing that getting it might lead to deportation—while many others whom the organization hasn’t reached don’t realize they’re eligible. “We have a combination of people who are eager and excited, while at the same time you have people who are fearful and who are just rejecting the vaccine completely,” said Rodriguez.

In the early days of the vaccination rollout, some undocumented migrants in Hidalgo County were turned away from clinics. Despite the guidance of the Biden administration about the eligibility of noncitizens, rollout management was left largely up to the states, which decided the order in which their populations would receive the shots. Some, such as North Carolina, opted to provide the vaccine at large without monitoring citizenship status. In Texas, things were a little more complicated at first. In February, sites administering the shots along the U.S.-Mexico border reported having trouble parsing “conflicting guidance” about the eligibility of noncitizens. For a few months, receiving a vaccine from at least four of twenty hubs in the Rio Grande Valley required either a driver’s license, social security number, or state ID, none of which undocumented migrants in Texas can get.

After one 61-year-old man was turned away from a vaccine center at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley in late February after he was unable to present a social security number, his son’s tweet recounting the incident went viral. UTRGV apologized, and a spokesperson has since clarified that the clinic no longer requires driver’s licenses or social security numbers. “We are not worried about residency status or citizenship status,” Hidalgo County public affairs director Carlos Sanchez told me.

The change in ID requirements encouraged some migrants to seek out the vaccine. One undocumented service employee who lacks health insurance, as do 80 percent of noncitizens in Hidalgo County, told me that getting a shot would allow her family to relax a bit after a year of frantically disinfecting work clothes after coming home from shifts at restaurants and construction sites. But other undocumented workers had heard stories of noncitizens, such as the 61-year-old man, being turned away from sites, and still operated on the old information that they might be required to present an ID.

In many cases, the misinformation is perpetuated by a lack of internet access. Most South Texas counties disseminate information on vaccination eligibility and appointments primarily through the web, but cities along the border with large noncitizen populations have some of the lowest rates of broadband connectivity in the nation. More than 47 percent of households in Brownsville do not have access to broadband internet, and in Hidalgo County more than 30 percent lack access. Rodriguez told me that one of her clients, an elderly undocumented woman without internet access, hadn’t known she was eligible for the vaccine until being contacted by LUPE. Even after the organization set up the appointment for her, the woman, who didn’t realize she’d have to go inside the clinic to receive the shot, struggled to walk across the parking lot. (Eventually, a LUPE team member noticed and assisted her.)

In other cases, migrants know they are eligible but fear receiving the vaccine could lead to deportation. Some recall the story of an undocumented fifteen-year-old girl from Edinburg who was arrested by Border Patrol last September after seeking gallbladder surgery. Although no deportation efforts at vaccination hubs have been reported, many immigrants are wary of providing personal data to state agencies and balk at letting their information be tracked by the Texas Immunization Registry. “Predominantly the ones that you see that are rejecting this vaccine are the male farmworkers that are here on their own without families,” Rodriguez told me. “They stay low; they don’t want to attend a clinic, provide information, or identify themselves.”

In the face of these challenges, LUPE has repeatedly returned to Hidalgo County’s agricultural fields to continue its registration efforts. In mid-April, Rodriguez registered 450 workers in the onion fields for the vaccine. She said some had declined her help, but she maintained that letting them know about their eligibility was an important step in its own right. Undocumented migrants “have the right to have access to a vaccine that might very well save their lives,” Rodriguez said. “And I don’t think anybody should be denied that.”

- More About:

- Health

- Rio Grande Valley

- Edinburg