The woman from Veracruz lay on the autopsy table, the first body Corinne Stern would examine that May morning. The Webb County medical examiner had to work quickly. The intake cooler was filling with the deceased, and more were expected at any time. She had to keep up with the dead.

The evening before, a Border Patrol agent drove on an unpaved ranch road outside Laredo, tracking migrants whose shoe prints he found hours earlier near the Rio Grande. A man in a white shirt stepped out from the dense brush and waved the agent down, pointing to a mesquite tree, and a body, saying “Muerta.” When the patrolman spotted her pale hands, he knew the young woman was dead. He checked her pulse to confirm. Ants crawled over her face and into her thick black hair. The woman’s Nikes matched some of the prints he found earlier.

The man in the white shirt said she was 23 and from Veracruz, seven hundred miles south on the Gulf. They had rafted over the Rio Grande with eight others in the mid-afternoon and had fallen behind their guide as he hurried through the scrubland. Shortly after getting lost, the woman died. One of Stern’s death investigators had taken the woman’s temperature: 108—the same as the air.

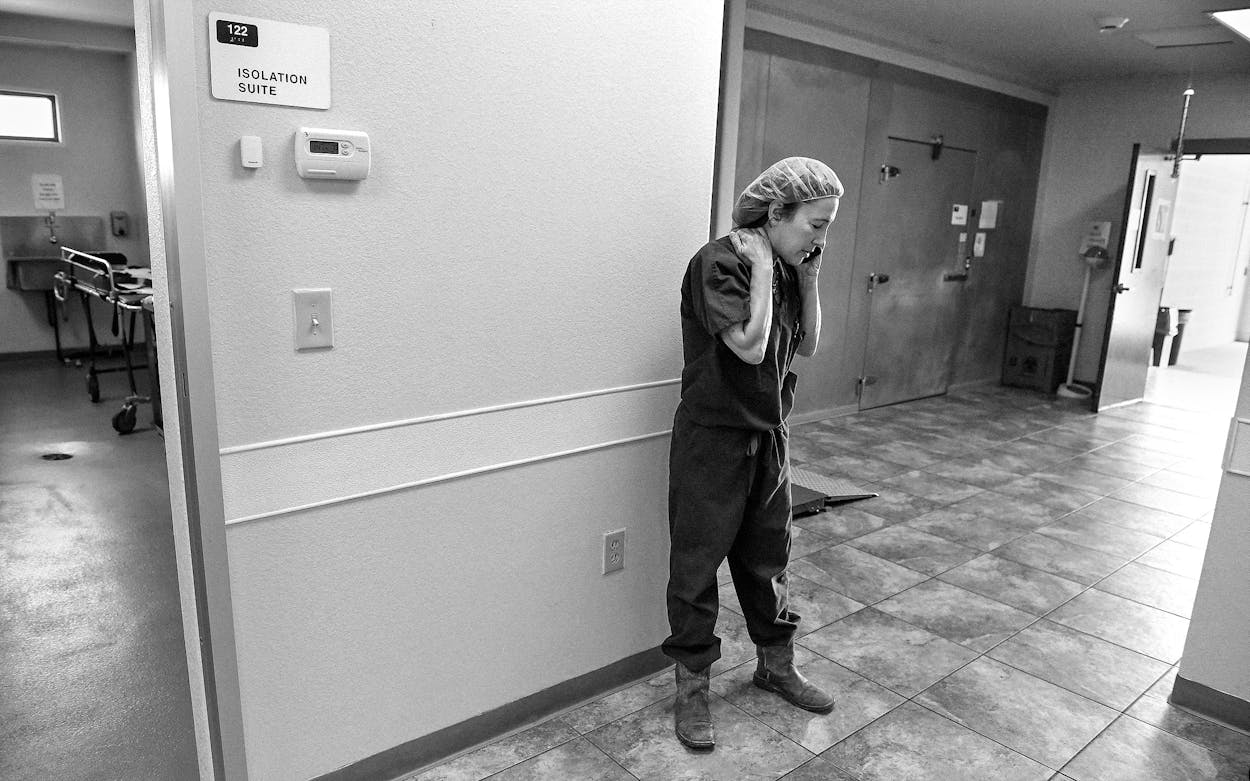

In the autopsy room, Stern noted that the woman had dressed too warmly: a thick, long-sleeved hoodie, long pants, pantyhose under the pants. Border crossers don’t know South Texas heat, Stern said, and the coyotes don’t warn them. Based on the woman’s high temperature, Stern listed the cause of death as heatstroke. She swabbed the woman’s nostril for a rapid SARS-CoV-2 test to determine whether it was safe to perform an autopsy to document a potential pregnancy. The test came back positive, so Stern’s staff placed the woman in a body bag and wheeled her outside to the quarantine cooler to await repatriation.

The woman from Veracruz was the eighty-seventh border crosser to die this year in one of the eleven South Texas counties Stern serves. Later the same day, six more migrants entered Webb County’s intake cooler. In her fifteen years as the medical examiner, Stern has never seen so many migrants die so quickly. By late May, the year-to-date count had ticked up to 116—double the usual number by this time. If the pace continues, 2021 will be the worst the Webb County medical examiner’s office has seen, with more than three hundred migrant deaths.

The migrants are mainly from Mexico and Central America, while a few are from Cuba, Haiti, Venezuela, and African countries. Juan Carlos Mendoza Sánchez, Mexico’s consul general in Laredo, described the current wave of migration as a social phenomenon. The migrants are “motivated by several ‘push and pull factors in both places of origin and destination, and whose cycles vary depending on the supply and demand of jobs.”

Republicans argue that Joe Biden’s softer rhetoric on immigration is encouraging more migrants to cross the border than did so during the comparatively harsher Trump administration. Many migrants say, by contrast, that Biden’s decision to keep the legal asylum process largely restricted is forcing them to cross illegally. In a press conference Monday in Guatemala on her first foreign trip as vice president, Kamala Harris issued a warning to migrants thinking of traveling to the U.S.: “Do not come.”

Experts say the perilous trek into Texas may be a migrant’s best option to escape gang violence, corrupt governments, and economic depression at home. “It’s hard for Americans watching TV to fathom if you’re not at the border,” said Steve Romero, a lecturer in criminal justice at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. “A lot of these people are starving. Coming here is basic survival, like what the Irish did during the potato famine.”

In May alone, Border Patrol encountered more than 90,000 migrants in South Texas. As the number of migrants crossing the border has shot up, so too has the number of migrant deaths. These days, Stern works eighty-hour weeks.

In a typical year Stern autopsies about 1,500 bodies with the help of dedicated technicians. Webb County is expanding the medical examiner’s office space and adding refrigerators to keep pace with the region’s population growth. Stern also wants to hire another forensic pathologist to balance the caseload, but finding someone willing to live at the border has been difficult.

The 55-year-old examiner, who grew up in Waco, has been drawn to forensics since she was a child. Early on, Stern wanted to be a psychiatrist, like her dad. But her father dissuaded her, believing that forensic pathologists had more freedom in their jobs. “I think the profession fascinated him, and I latched onto the idea,” she said.

In 2000, after years of medical training and a fellowship at the Office of Armed Forces Medical Examiner, Stern began her career as a forensic pathologist in El Paso. She took a job in Alabama in 2005, but left after state officials scrutinized one of her autopsies that led to homicide charges against a mother that were later dropped. (Stern still stands by her conclusions.) She returned to Texas in 2006, taking over the medical examiner’s office in Webb County, where the job frequently calls for identifying the undocumented. Stern loves her profession and considers herself a physician and a detective.

She says her two decades of work have taught her that you can be gone in a blink of an eye. “I live every day like it’s my last and put nothing off,” she said. “I always make time for what’s important, but I never sacrifice my job or staff.”

Out of respect, she refers to the dead as patients, not bodies. Later in the day, another patient, John Doe number 505, mummified on Stern’s autopsy table. Flies circled in the air, and hundreds of maggots crawled onto the floor. In mid-April a Mexican national had filed a missing-person report for her brother-in-law, and said he was lost somewhere between Dilley and Cotulla. Border Patrol searched GPS coordinates provided by the sister-in-law on April 14 but found no one. On April 29, a helicopter pilot spotted a body on a ranch in the area.

Stern examined the Mexican voter-ID card found on John Doe. Could he be the missing brother-in-law? The card had a large, clear embossed fingerprint on the back. Maybe 505’s fingerprint photo would match the voter card. “Identifying them is the most complicated part. You can’t rely on border crossers carrying the right ID,” she said. “Some justices of the peace just accept a card in the pocket and send them home. I won’t send someone back without ID’ing them.”

In her office, Stern emails the Mexican consulate with photos of John Doe’s decayed finger and the voter card. An incoming email solved another case for the pathologist. A family in Mexico sent an image of a missing relative’s heart-shaped tattoo. It matched a tattoo on a migrant found in Webb County a week earlier. “I’ll notify the consulate,” said Stern. “He gets to go home. I don’t want anyone forgotten.”

- More About:

- Laredo