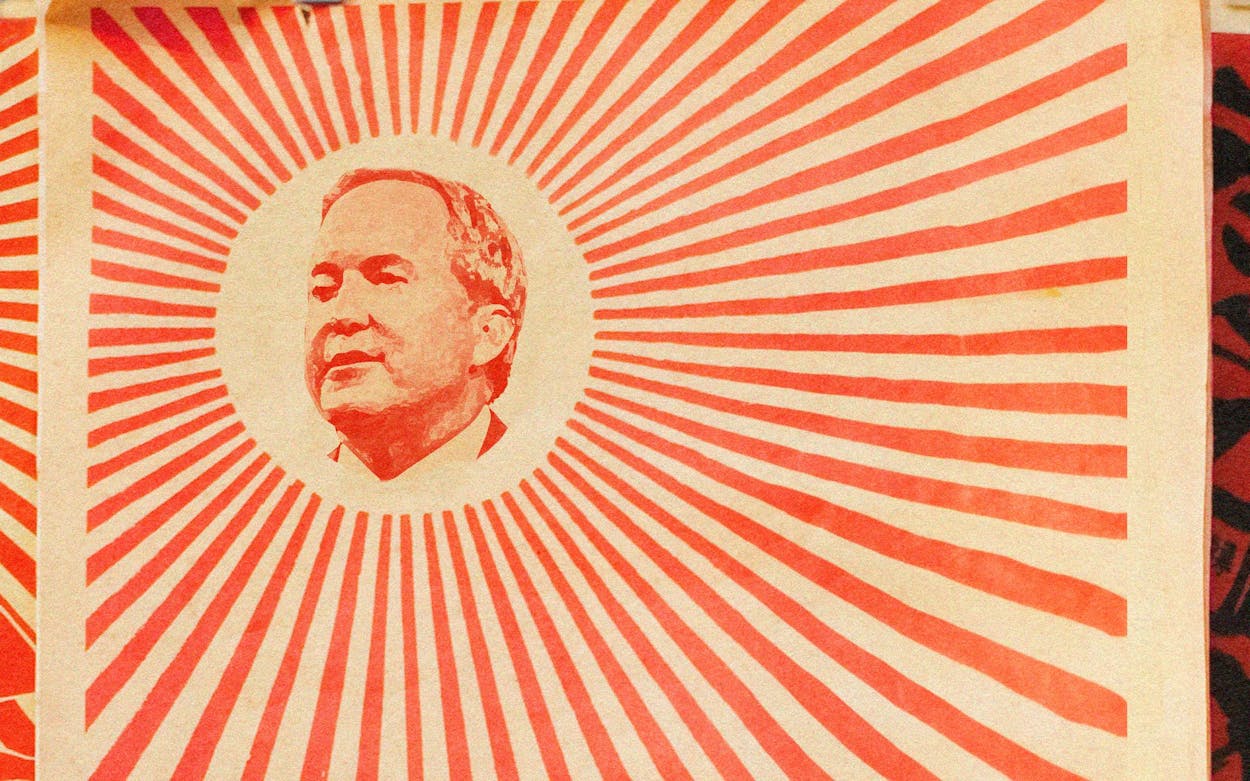

Do you support Ken Paxton, the embattled and impeached Texas attorney general? Would you champion him online for, say, $50? That’s not just a theoretical question. Before the start of his impeachment trial this week, pro-Paxton political forces were paying for influencers to post on social media in support of the state’s top legal authority, who faces sixteen counts ranging from dereliction of official duty to bribery and conspiracy.

How do I know this? Because I signed up to be a social media influencer, and to my great surprise, I earned $50 for each of two posts. I received an email confirming payment on Tuesday morning, mere minutes after the state senators placed their hands on the “Sam Houston Bible” (which likely didn’t actually belong to Sam Houston) and took an oath to be impartial jurors.

Paxton is facing a fight for his political life. If the Senate finds him guilty of any of the charges, it will effectively end the career of a man who rose from the back benches of the Texas House to become a celebrated antagonist of Democratic presidents. The trial is about more than one person, however. It is also a litmus test of who holds power in Texas and a battle for the soul of the state GOP. (There are Democrats on the jury and in the mix, too, but this is Texas, and they’re not particularly relevant to the conversation.) Paxton’s impeachment in the Texas House was spearheaded by what remains of the moderate, chamber of commerce wing of the Republican Party. His potential ouster is opposed by the state’s MAGA right wing, which is financially backed in large part by Tim Dunn. Allies of the Midland oilman and Christian nationalist have vowed to fund primary challengers against any Republican who votes to give the attorney general the boot.

Into this turbulence, an unidentified group put out calls for tweets in support of Paxton. They were first reported on by Current Revolt, a far-right online publication that bills itself as the “Texas Newspaper of Record.” Earlier this month, I found a link to a Google form to sign up for payments. So, out of curiosity, I signed up.

My first tweet was a link to an article on TexasMonthly.com that provided a snapshot of the lawyers, witnesses, and others likely to be involved in the trial. “Do you confuse Jake Paul with Nate Paul?” I asked. “Do not fear. [Mimi Swartz] has delivered the ultimate cheat sheet.” My second tweet was even more anodyne. “Will he be found guilty? Or innocent? I’m on tenterhooks!” I exclaimed, in what was intentionally a down-the-middle and, frankly, cheesy tweet.

I logged the tweets into the Google form and signed up with a website, as instructed, that handled payments. I used my real name and my Texas Monthly email account. I figured that would be the last I heard of the matter. Then came the $100 deposited into my account. The payer was Candice Parscale and Influenceable LLC. Candice is the wife of Brad Parscale, the former head of digital operations for Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign. The couple has recently moved back to Texas from Florida, and as I reported last week, Brad, who declined a request for an interview, is newly allied with Dunn and living near him in Midland.

Before I go on, a word about the $100 and beef. Here at Texas Monthly, we have a thing for brisket that practically melts in your mouth. We throw a BBQ Fest every year to celebrate the state’s pitmasters. But we’re also mindful that many Texans suffer from food insecurity. So in conjunction with BBQ Fest, we raise money for Feeding Texas. I took my $100 payment and donated it to that nonprofit.

Back to politics. Who is financially backing the AstroTurf support for Paxton and funding the checks like the one I received? The money I got was funneled through Influenceable, which pitches itself as a platform for “brands, organizations, and campaigns in the anti-woke economy.” But the name of the payer is obscured. From the looks of the invoice, Candice Parscale appears to be the bookkeeper, not the bankroller. Someone is out there writing checks to influence our politics, paying accounts to tweet about Paxton, and we don’t know who that is.

Whether or not this is legal is unclear. I consulted what amounted to a “Political Advertising Laws for Dummies” document on the Texas Ethics Commission website. It wasn’t helpful, and the experience felt similar to trying to diagnose what’s wrong with your Tesla Model S by reading a manual on how to fix a 1972 Volkswagen Beetle. So I called the Ethics Commission’s top lawyer, James Tinley. He said there was no specific guidance addressing social media influencers, but that “generally, state law requires a disclosure statement on paid political advertisements that expressly support or oppose a candidate or public official.”

This whole area is new and emerging. Perhaps we need guidance from the attorney general’s office. Or, on second thought, perhaps not just yet.

The use of social media influencers to promote political candidates—or any product—is becoming more common. A decade ago, we saw the rise of bot armies, computers programmed to flood social media. But the platforms got wise to this and, under pressure from regulators and others, clamped down.

Political campaigns and marketing companies got creative. They assembled armies of actual humans, small-scale social influencers, to pump out a message. They’re called nanoinfluencers. (Think a twenty-year-old in El Paso with 1,500 followers, not Simone Biles.) “It’s really brilliant and very worrying” because it is effective, said Sam Woolley, director of the propaganda research lab at the University of Texas at Austin. He’s worried that influencers could short-circuit the democratic process. Politicians who benefit from this pay-to-post machine will become less focused on their constituents and “more likely to be beholden to the powerful interests that have supported them.”

I asked Woolley a question that had been bothering me. Why was I paid? I assumed it was a computer churning out checks without examining the content of posts, since my tweets weren’t offering an effusively pro-Paxton message. Did I dupe Influenceable? Not at all, Woolley replied. My tweets—and others—created engagement around the Paxton impeachment trial, in turn teaching the social media site algorithm that this was an issue users were interested in. In turn, my posts increased the likelihood that Twitter (or X, as it’s now known) would promote Paxton-related tweets. That would allow other paid posts that more effusively proclaimed Paxton’s innocence to spread further and wider. “The secret sauce on social media is getting things to go viral,” Woolley said. “Otherwise you’re just speaking into the ether. And so you’re contributing to allowing posts to not just go into the ether.”

“Did I become a paid propagandist?” I asked him directly.

“Yeah, you did,” he said.

I consider myself a fairly sophisticated purveyor of political information in the media, having been a member of the fourth estate since before Mark Zuckerberg applied to college. But Woolley was telling me that I had become the dupe, a cog in a Rube Goldberg contraption to fool powerful computers.

“What should I do to earn absolution?” I asked Woolley.

“Write the story and let people know that this is happening,” he replied. “Because a lot of people don’t know this is happening.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Ken Paxton