When Isabel Longoria took office as Harris County elections administrator shortly after the November 2020 presidential election, she knew that running elections for Texas’s most populous county would be a challenge. There were new voting machines to deal with, a staff of 360 full- and part-time employees to oversee, and a fractious relationship between the local Democratic and Republican parties to negotiate. Almost immediately, though, Longoria found herself responding to a different challenge: President Donald Trump’s baseless claims of a stolen election.

Following Trump’s lead, right-wing Texas activist Steven Hotze had raised hundreds of thousands of dollars to investigate alleged election fraud in Harris County, where voters favored Joe Biden by a thirteen-point margin. In December, one of Hotze’s investigators was arrested for holding an air-conditioner repairman at gunpoint in the run-up to the election while searching for 750,000 fraudulent mail ballots. No ballots were found; Hotze and the investigator have been indicted on charges of unlawful restraint and aggravated assault with a deadly weapon. Other local groups, such as Houston-based True the Vote, continued to spread misinformation about the 2020 election.

Longoria did her best to assuage the concerns of election deniers. She gave several “stop the steal” activists tours of her office. She showed them the new voting machines, which—contrary to what many conspiracy theorists believe—are not connected to the internet. She invited them into the central counting center for the 2021 primary elections. “We developed a very good rapport,” Longoria told me. “I got to the point where one woman said, ‘I believe you. I don’t think you’re trying to steal the election. But I think these machines are Wi-Fi-controlled and that you’ve been fooled.’ It was that level of absurdity.”

Longoria resigned in March after receiving bipartisan criticism for her management of the primary elections. Her replacement, Clifford Tatum, who took office in August, is now dealing with many of the same pugnacious election deniers, who have not been mollified.

Indeed, election administrators across Texas have spent much of the past two years shooting down right-wing conspiracy theories about voter fraud, none of which are supported by evidence. Even in a state that Trump won by five percentage points, a significant proportion of Republicans are convinced that the election here was marred by fraud. A February 2021 poll conducted by UT-Austin’s Texas Politics Project found that just 30 percent of Republicans considered the state’s election results “very accurate,” compared to 65 percent of Democrats. Just one in five Texas Republicans believes President Joe Biden legitimately won the 2020 election.

The conspiracy theories about fraud, which often originate on social media or fringe websites before making their way to mainstream outlets, have led to widespread harassment of election officials. After longtime Republican stronghold Tarrant County, whose seat is Fort Worth, narrowly voted for Biden in 2020, local elections administrator Heider Garcia—a former employee of the voting-machine company Smartmatic—was targeted by Trump attorney Sidney Powell, of Dallas. “Gee whiz! I wonder how #TarrantCounty Texas went #blue so easily after hiring a #Smartmatic guy?!” tweeted Powell, who spearheaded the legal effort to overturn the 2020 election. After Powell’s smear was picked up by Fox Business and Newsmax, a Twitter user posted Garcia’s home address. He and his family began receiving graphic death threats. “We are getting Donald Trump and you are getting a trial for treason,” one man wrote to Heider on Facebook Messenger. “I think we should end your bloodline.”

A national survey conducted in January and February by the Brennan Center for Justice found that one in six local election officials has experienced similar threats. Last year, the Department of Justice launched a task force dedicated to combating the rise in threats against election workers. It brought its first criminal case against a Texan, Leander resident Chad Stark, who allegedly posted a message on Craigslist calling on “patriots” to “put a bullet” in three Georgia officials he believed to be Chinese agents. The DOJ task force has reviewed more than one thousand other incidents of hostile or harassing behavior across the country, around 11 percent of which “met the threshold for a federal criminal investigation.”

Amid the pressure, nearly a third of Texas election officials have quit or retired since 2020, according to the Secretary of State. “The rhetoric and the environment has changed so dramatically in the past couple of years,” said Remi Garza, the elections administrator in Cameron County, home to Brownsville, who also heads the South Texas region of the Texas Association of Election Administrators. “We’ve seen retirements. We’ve seen people talking more seriously about this being the last election they’re going to administer. They don’t want to face what could come during the 2024 presidential election.”

The election officials in Gillespie County, about eighty miles west of Austin, didn’t wait that long. In August, elections administrator Anissa Herrera and her two deputies quit after years of harassment from far-right conspiracy theorists. In her resignation letter, Herrera wrote that “the threats against election officials and my election staff, dangerous misinformation, lack of full time personnel for the elections office, unpaid compensation, and absurd legislation have completely changed the job I initially accepted.”

By “absurd legislation,” Herrera appeared to refer to Senate Bill 1—the controversial election law passed last year by the Republican-controlled Legislature, in direct response to Trump’s claims of a stolen election. The law eliminated 24-hour voting centers, drive-through voting, and the solicitation of vote-by-mail applications. It relaxed restrictions on poll watchers (who sometimes seek to intimidate urban voters), increased penalties for voter fraud, and—perhaps most consequentially—imposed onerous new vote-by-mail requirements that resulted in more than 12 percent of mail-in ballots being rejected in this year’s primary elections.

Retiring state representative Lyle Larson of San Antonio, the only Republican legislator to vote against SB 1, told me the point of the bill was not to combat voter fraud, but to make it harder to vote in urban areas, which tend to be Democratic. “There’s a misrepresentation that we had an election that was fraudulent,” Larson told me. “So we passed a series of laws that deal with something that was fabricated.” He said that even Republican legislators who voted for the bill have privately admitted to him that there is no widespread voter fraud. “Most people who are sensible know that this is all bullshit.”

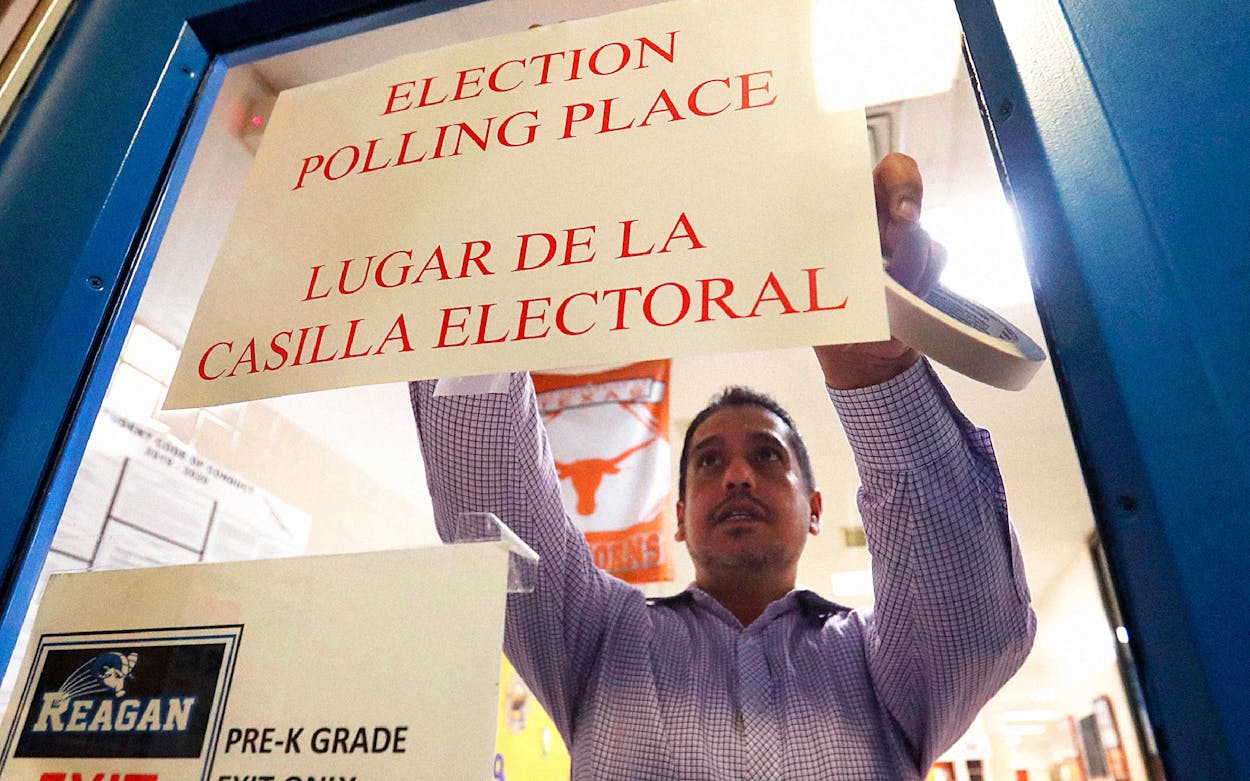

In the wake of mass retirements, elections administrators are busy trying to recruit and retain election judges and deputies. To ensure the safety of those workers, many counties have created emergency-response plans involving sheriff’s deputies, local police departments, and private security. Dallas County elections administrator Mike Scarpello told me that his office will also launch a “rumor control” page on its website to rebut conspiracy theories in real time. Tatum, the new Harris County elections administrator, plans to invite members of the public and the news media to tour election headquarters this month.

As always, though, come November, it will be the tens of thousands of volunteer election judges across the state who will be on the front lines, conducting the election. Many don’t understand why the mundane business of running a polling place has become so controversial. Sherrie Matula, who has worked as a Democratic election judge in Harris County for forty years, recently decided to retire because she doesn’t like the county’s cumbersome new voting machines. Given her extensive experience with local elections, she has little patience with conspiracy theorists. “No one who is making all these claims has actually sat down and worked an election,” she told me. “If they had actually gone through and done all the work, they wouldn’t be saying that stuff. They would be saying that this could never happen.”

Martin Renteria, who has served as a Republican election judge in Spring, a suburb north of Houston, for eight years, likewise dismisses sweeping claims of electoral shenanigans. “The Democrats I’ve worked with are fine people,” he told me. “I work well with them. I know them personally. And you know, I don’t see any evidence whatsoever that the folks I work with are involved in election fraud. They want fair elections, like I do.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Houston