Late last month, Senator Ted Cruz stood beside a pulpit at the Texas Faith, Family, and Freedom Forum, hosted by Texas Values, a conservative policy group based in Austin, and made the case that liberal insanity in Washington was worse than he’d ever seen it. He took Trump-style potshots at the appearance and scruples of his opponents—in this case a handful of congressional Democrats. “Five years ago in the Senate there was one open and avowed socialist,” Cruz said, referring to Bernie Sanders of Vermont. “Crazy uncle Bernie, white hair standing straight up. By the way, would it kill the guy to use a comb? I mean he’s a socialist, he can just take one from someone.”

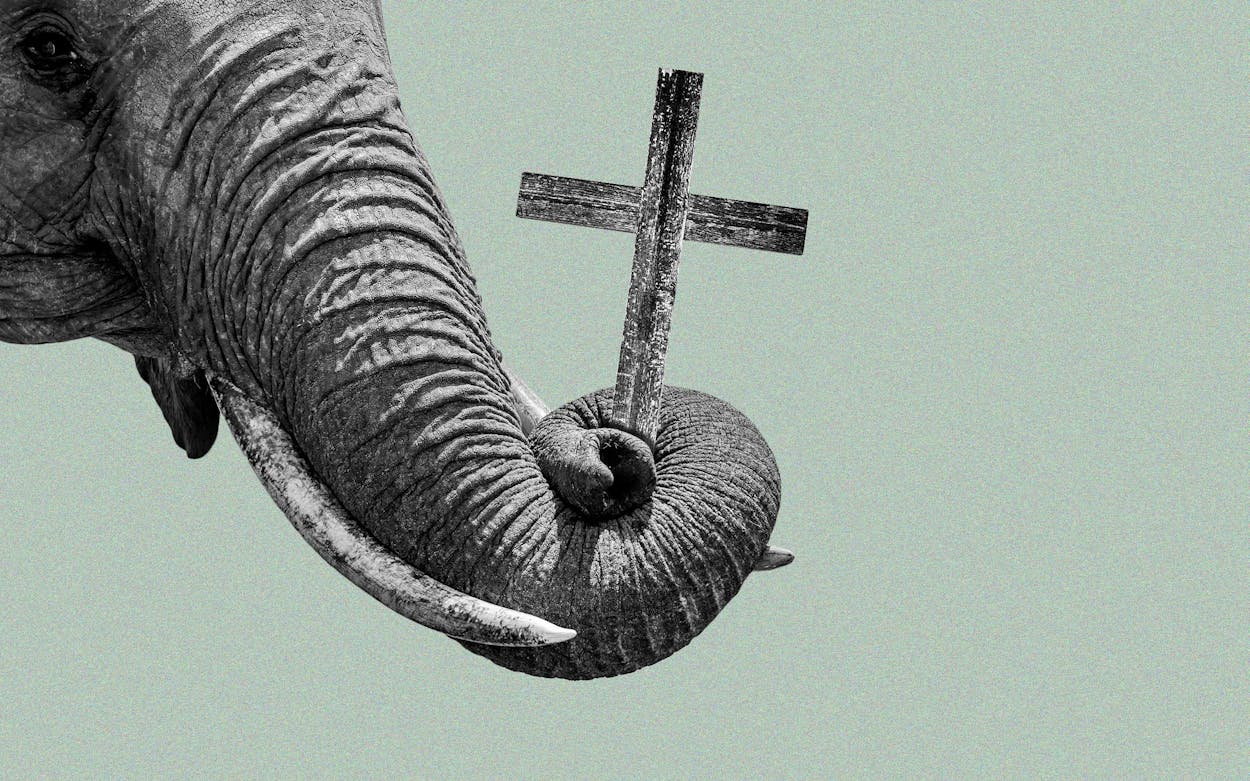

Calling Democrats lunatics is standard practice for Texas’s junior senator. But mixed in with his jeremiads were other signals more fitting to the setting, a stage at Austin’s Great Hills Baptist Church with a large cross adorning the podium beside him. “A revival is coming,” said Cruz, the son of an evangelical Protestant minister. And while he added that politicians like him were ready to lead it, he also reminded those gathered that much of the public still needs to be won over. “We need to do a much better job as evangelists,” Cruz said. “Evangelists for Jesus, yes, but also in the public sphere as evangelists for liberty, for our values.”

Cruz blended explicit biblical language and patriotic imagery throughout what was, at its core, a speech to rally the political activism of the “joyful warriors” convened that evening by Texas Values, which itself makes little distinction between Republican, Christian, and American priorities. The group’s website explains its position that “government is an institution ordained by God, with the purpose of punishing evil and rewarding good” and adds that “those who serve in government are God’s ministers.” A cross-shaped graphic accompanying the term “Religious Liberty” on the homepage makes clear to which religion’s God the group is referring.

Employing religious language in political speech is hardly new, even in less explicitly Christian settings. Expressions of ceremonial deism, such as reciting “one nation, under God” in our national pledge and emblazoning “In God We Trust” on U.S. money, have been part of our civic life for generations. But in a country with no official religion, the use of Christian scripture and distinctly Christian language in public speech is notable, particularly amid concerns about rising white Christian nationalism. The phrases and even the Bible verses are likely familiar to religious and nonreligious Texans alike, where megachurch pastors and Bible-quoting politicians have built massive platforms. In his book Rough Country, Princeton sociologist Robert Wuthnow describes how Texas became “the Bible belt’s most powerful state,” shifting from a largely Catholic culture with San Antonio as its commercial center to an evangelical culture with Dallas as the hub. The book, and Wuthnow’s other research, looks at American religion in the context of social change, political movements, and commercial interests. This area of research now includes the ascent of Donald Trump and his marshaling of white evangelicals, 80 percent of whom voted for him in 2016.

The effectiveness of Trump’s championing of white evangelicals’ priorities was striking: most forgave the notorious playboy for his coarse speech, cruelty toward the downtrodden, and flagrant immorality. Trump also eschewed the kind of civic unity that requires politicians to use broad language, and opened the door more widely for the public promotion of a single religion. A perusal of Texas’s statewide officeholders shows a number of tweets, stump speeches, and television appearances heavy with a specific expression of evangelical Christianity.

After the Texas Supreme Court sided with cheerleaders in East Texas in August 2018 and allowed them to display a verse from the New Testament on their football team’s run-through banner, state attorney general Ken Paxton tweeted in support. “God bless these young cheerleaders for their faith in God and their fight to protect their religious liberties. Just like their banners said, ‘I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me.’” The verse, taken from St. Paul’s letter to the Philippian church, references the apostle’s spiritual growth, which allows him to endure the unpredictability—including hunger and financial need—in his missionary work. The verse has become popular among athletes, politicians, and other competitors as a triumphalist blessing over their ambitions. It would be better applied as a way of saying “I’ll be fine, even if I lose, because God’s kingdom doesn’t depend on a football game or an election.” But that’s not the message Paxton is sending in the tweet. His public messaging and that of other top Texas politicians implies that the kingdom of God very much depends on who wins elections.

The sincerity of politicians’ religious statements is impossible to determine, Wuthnow told Texas Monthly, but it is possible to look at how the statements function in society as more of what he calls a “signaling process.” That analysis looks less at intention and more at the context of what is being said. It’s not dissimilar to what makes a joke funny. When Cruz was speaking in the context of the Texas Values forum, he could refer to America as “a shining city on a hill”—quoting Ronald Reagan’s reference to Puritan John Winthrop’s 1630 sermon citing Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:14)—and shortly after refer to law professor Khiara Bridges, who had a tense exchange with Missouri senator Josh Hawley over gender-inclusive language while testifying on the impact of overturning Roe v. Wade, as “crazy eyes,” with equal effect. The can-you-believe-this-nonsense humor found its target, because Cruz knew going into the speech that most in the audience shared his definition of nonsense.

The “city on a hill” reference, though ripped from its original context in Jesus’s famous call to humility and good works, efficiently signaled Cruz’s commitment to a form of religious liberty, which, as the examples sprinkled throughout his speech made clear, means freedom from the expectation that Christians will use gender-neutral language or be required to enact anti-discrimination policies in their churches or schools. “Religious speech is a signal about religious freedom more than it has been in the past,” Wuthnow said. By using religious language, the more explicit the better, he said candidates can demonstrate their willingness to bring faith into the public sphere, an idea supported by many—including 89 percent of white evangelicals, who believe the Bible should have an influence on U.S. laws.

That repeated signal has muddied people’s understanding about what kind of religious liberty is actually guaranteed by the Constitution, said Amanda Tyler, executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, based in Washington, D.C. “I think there’s great confusion in the culture about what is meant by religious freedom or religious liberty, and that is because there has been a concerted effort to privilege Christianty and call it religious liberty.” Cruz demonstrated that rhetoric, arguing that the First Amendment specifically protects the founding ideal that “you and I could seek out and worship the Lord God Almighty with all of our hearts, minds, and souls,” a phrase from the Hebrew shema prayer in the Old Testament and repeated by Jesus in the Christian Gospels as “the greatest commandment.” While the Constitution guarantees the free exercise of religion in broad language, Cruz linked the rights spelled out in the First Amendment directly to his Christian audience. It may be worth noting that in both the Old and New Testaments, the command to worship God with one’s whole being is given to followers who subsequently will face jail and execution by the state for the exercise of their religion. They were urged to do it anyway because God’s spiritual kingdom, as presented in the Bible, is not dependent on political power or even favor. Both the Hebrews and the early Christians faced larger threats than being “canceled” by the free choices of private platforms and consumers, which Cruz specifically mentioned in the opening of his address as a sign of how far the country has fallen.

Cruz’s belief that Christian values should be codified into law has been a hallmark of his ten-year Senate career and his failed 2016 presidential bid, leading some to describe his politics as Christian nationalism. That movement asserts that the United States should be an explicitly Christian nation, with laws subject to the Bible—not exactly a caliphate in theory, but in practice not far off. In a report on the role of the explicitly white supremacist Christian nationalism in the January 6 insurrection, University of Pennsylvania professor Anthea Butler points out that white Christian nationalism promotes specific ideas not only about the nation but about Christianity: referencing the prayer offered in the Senate chamber during the January 6 insurrection, Butler identifies white Christian nationalism as upholding “the assumption that Christ is at the core of efforts to establish and promote white Protestant Christianity in the service of white male autocratic authority.”

Of course, many politicians can express their personal Christian faith without compromising their duty to uphold the constitutional right to equal citizenship for people of all religions. Christian leaders might reference personal faith and values that guided their support for a particular policy without making “second-class citizens” of non-Christians, said Tyler. They can strike that balance as long as they are not sending the signal that they govern only on behalf of people who share their beliefs. The First Amendment—which Tyler argues was written in defiance, not support, of the Puritans’ “shining city on a hill” aspirations—has allowed many elected and nonelected people to share diverse religious ideas and convictions in the public sphere, without heavy-handed government enforcement. “Keeping government out of religion has allowed religious pluralism to flourish in the United States,” Tyler said. “Everyone belongs equally no matter what we believe.” But elected leaders who choose to be open about their own faith need to be wary of blurring the line between religion and the Constitution, Tyler noted—not only in the laws they fight for and the way they talk about them but in how they promote ideas of who is and is not fully American. “Repeating the myth of Christian nation also perpetuates Christian nationalism and leads to this us versus them mentality.”

Even politicians who would not advocate a state religion can blur that line, because of the context in which they are speaking. When Dan Patrick refers to a Gallup poll indicating a declining belief in God and posts, “At this moment in time, we’re in more than just a battle between Republicans and Democrats in this country; we’re in a battle of darkness and light,” he may not have white Christian nationalism in mind, but the signal will be understood by voters and funders who do. The signal will most likely reach older, white, conservative voters who regularly express concerns about cultural changes in the United States, especially through nonwhite migration and religious pluralism. “They’re the kind of people who want to remember the good ol’ days when everybody was a Christian just like they are,” Wuthnow said.

Nostalgia for the good ol’ days, however, is rarely where the signals stop. To attribute declining religiosity, especially among the young, to complex factors wouldn’t rustle up votes and tithes nearly as effectively as the message that Christianity is “under attack,” a signal sent frequently to generate fear, which psychologists say is a powerful motivator in elections.

Whatever the cause, the declining proportion of Americans who identify as religious Christians drives a lot of the anxiety in another key group, Wuthnow said: pastors. Coded speech about bringing religion into the public sphere is “also a way to talk to the megachurch leaders,” Wuthnow said. Leaders such as Robert Jeffress of the 14,000-member First Baptist Church in Dallas have grown more outspoken in their support of candidates who vow to protect a version of religious liberty that ensures they can, among other things, refuse to cover birth control in their employees’ health benefits and can practice discriminatory hiring in the various schools and ministries attached to their churches. When political issues and biblical language appear together in both the news and the pulpit, politicians and pastors benefit from a rhetorical tradeoff—pastors can stay relevant to the national conversation and hopefully continue to pack the pews, and the politicians benefit from the deeper trust worshippers have in their pastors.

Republicans may be trying to re-create that magic with Hispanic voters—a demographic that is more religious than non-Hispanic whites, and one that is growing rapidly as the white majority shrinks. The gap between the number of Anglo and the number of Hispanic eligible voters in Texas was cut in half between 2000 and 2018, according to Pew Research. There had been a widespread assumption that Hispanics, because many are Catholic, would vote for candidates opposed to abortion rights, but recent polling data indicates otherwise. Both Catholics and evangelicals (50 percent and 14 percent of the U.S. Hispanic population respectively) may personally agree with Republicans that life begins at conception, but Hispanic voters have more nuanced views about the circumstances under which abortion should be legal, and polling indicates the majority do not want to see it outlawed. That could make the messaging more complicated for Republicans, who often lend their position an air of authority by linking abortion restrictions to religion.

“By God’s grace, we can give every child the chance to live a happy and fulfilling life,” said Governor Greg Abbott in a statement proclaiming January 22, 2018, to be “Sanctity of Human Life Day.” The use of “by God’s grace” in public addresses could refer to any number of verses in the Christian Bible, and in public speech it often occupies a middle ground between ceremonial deism such as “in God we trust” and something more personal. But in politics, the phrase is closely related to “By the Grace of God” or “Dei Gratia,” which is part of the way that European Christian monarchs have been ceremonially addressed. It was a phrase added to their names to imply that their authority was a gift from God. Not enough American voters likely know about the European uses of the phrase to receive that signal. But the idea that God lent divine favor or power to a particular ruler or endeavor is potent, especially when fostering a discourse that there is indeed a fight to be fought. The appeal to a higher authority as the direct source of legal rights—making the Constitution somewhat like a catechism clarifying infallible doctrines of God in the public sphere—is useful for politicians attempting to prevent progressive laws from being passed, and unpopular laws from being amended.

In a July 2021 amicus brief for New York State Rifle and Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen—which successfully challenged a 1911 New York law allowing local law enforcement discretion over who may be issued a handgun permit—Abbott preempted any question of reinterpreting the Second Amendment by pointing to God-given rights. Whether a knife, a gun, or a cannon, he argued, the right to bear arms is granted by God. “Texans have long cherished the right that was confirmed by the Second Amendment, but conferred by God,” Abbott wrote. In a 2019 Twitter exchange about gun rights with actress Alyssa Milano, Cruz cited Exodus 22:2, which granted the Hebrews permission to beat an intruder to death. “The right to self-defense is recognized repeatedly in the Bible,” Cruz tweeted.

Of course, when an assault rifle is used to murder children in a school, politicians call upon their faith to signal the sincerity of their condolences—to maintain public trust. While the vaguely religious expression “thoughts and prayers” is often met with sneers—that signal is now used by gun reform advocates to condemn cynical inaction—it’s harder to dismiss more ornate condolences, as Patrick used on Tucker Carlson Tonight the day of the shooting in Uvalde. “We have to unify in prayer, we have to unify in faith,” Patrick said, visibly emotional. “Hope, in the Bible, Tucker, says that’s the hope we have: to be rejoined with our loved ones.”

But looking forward to heavenly reunions wasn’t the only religious sentiment Patrick pushed after the massacre. Another message came through loud and clear at a town hall in Uvalde the next day. “Evil will always walk among us,” Patrick said, “It’s God that heals a community . . . If we don’t turn back as a nation to understanding what we were founded upon and what we were taught by our parents and what we believe in, then these situations will only get worse.” Amid the tragedy, he’d found the signal.