Bee Matthey, a nineteen-year-old junior at Baylor University, feels lucky. As a nonbinary student at the largest Baptist university in the United States, they hear the stories of harassment on campus and know that making it to their junior year relatively unscathed is a blessing. “I’ve never been scared,” Matthey said, shrugging off what they call “random microaggressions.” For example, “I definitely have had people tell me ‘you’re going to go to hell.’ ”

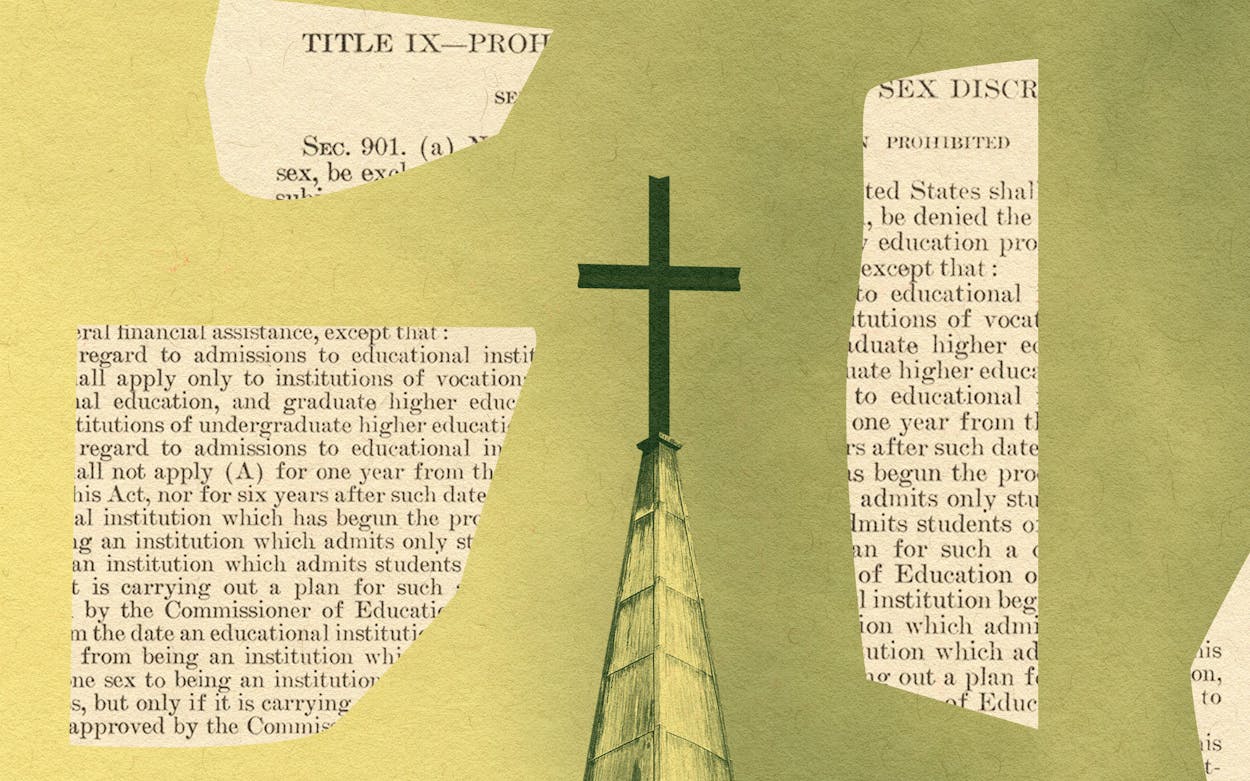

Matthey is not alone. Queer students at Christian colleges hear direct or implied condemnation all the time. Baylor alum Veronica Penales, in a high-profile lawsuit following a Title IX complaint filed against Baylor in 2021, reported receiving a Bible with all of the so-called “clobber verses”—Scriptures that appear to condemn homosexuality—highlighted.

When leveled at queer students, the explicit or implied phrase “you’re going to hell” sits at the intersection of religious belief, freedom of expression, and hate speech. It is a theological assertion, hollowed of evangelistic sincerity, used as a statement of condemnation and exclusion. The overlap, sociologically, of people who consider it sinful to be queer, and people who believe in some version of eternal torture is significant—about 41 percent of people who believe in hell also believe that homosexuality should be discouraged. (Yes, there is Pew Research data on this.) It is technically a religious belief, and, however hatefully it might be intended, it is a sentiment Americans are free to express.

But it’s the kind of speech that, if pervasive, could violate Title IX, the federal civil rights law that prohibits sex-based discrimination, says Laura Johnson, Baylor’s Title IX coordinator. And at the school, it would be addressed as such, she said.

In order to violate current Title IX law, harassment must be severe and pervasive. Pervasiveness can be a high bar to meet, and the Biden administration has suggested it would lower it by changing that “and” to an “or.”

This was the imminent change that Baylor said led it, in May, to ask the U.S. Department of Education to reaffirm the school’s religious exemption from Title IX, originally granted in 1985. Outrage ensued—the timing and circumstance of the request, which was granted in August, coincided with open investigations into sexual harassment at the school. According to Johnson, the request wasn’t filed because the institution condones the use of homophobic slurs, but because the new definition would mean the university’s policies—such as its statement on human sexuality, which codified the university’s long-standing concurrence with Baptist doctrine on the issue—could be grounds for a Title IX complaint. That statement, which emphasizes “purity in singleness and fidelity in marriage between a man and a woman as the biblical norm,” isn’t severe, in that it doesn’t explicitly condemn anybody. But as official policy, it is pervasive, Johnson said. Without a religious exemption, administrators worry even the school’s statements about its religious beliefs could earn a Title IX violation, opening it up to lawsuits or even result in the withdrawal of federal funds.

The expected rules are part of several changes to Title IX guidance the Biden administration proposed in 2022, but has yet to adopt, prompting frustration from student groups. (Johnson says Baylor’s policies already meet many of those anticipated changes: its student conduct policy applies to students both on and off campus, and harassment protections explicitly apply to gender expression and sexual orientation.)

When and if new rules are put in place, Title IX lawyer Alexandra Brodsky told me, it will be up to the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR) to determine exactly what religious exemptions cover. A school may have an official position on human sexuality based on religious ethics, but it would be hard to argue religious grounds for allowing students to be harassed in any way, even if the harassment was based on a religious belief. It’s an open question, Brodsky said, “how significant this religious exemption is.”

In the letter requesting reaffirmation of Baylor’s religious exemption in response to a case currently before the OCR, university president Linda Livingstone specifically cited exemption from Title IX action on “the University’s alleged response to notice that students were subjected to harassment based on their sexual orientation and/or gender identity.”

The university wouldn’t clarify to what degree the letter was referencing Penales’s case, as it is the subject of an open investigation by the federal government. But activists see Penales’s complaint that sexual harassment was at times tied to religious statements as an example of why exemptions need to be more closely scrutinized. With such an exemption, a religiously affiliated university could draft a relatively toothless anti-harassment policy while claiming that it is guided by religious principles, said Paul Southwick, executive director of the Religious Exemption Accountability Project (REAP), an advocacy organization for LGBTQ students on Christian college campuses. While he hopes Christian colleges and universities that receive public funds would treat religiously worded sex-based bullying—i.e., telling LGBTQ students they’re “going to hell”—with seriousness, right now they have the legal right not to.

In the fifty years since Title IX became law, OCR has not denied any institution a request for a religious exemption. Such exemptions were relatively rare—about 165 in the first forty years of Title IX—until the Obama administration issued guidance to extend the definition of sex-based discrimination to include LGBTQ students. The years immediately following saw more than 100 new exemption filings. They essentially allow the university to proceed without worrying about whether particular conduct and disciplinary policies follow the rules of Title IX, in theory, as long as those policies are dictated by religious beliefs. When trying to avoid a lawsuit, religious exemptions cover a multitude of sins.

In 2021, REAP published the findings of a survey of students at 134 U.S. Christian colleges and universities that accept public funding. It found that more than 10 percent of students identify as LGBTQ, and that students who identify as a gender minority are five times more likely to be bullied than their cisgender peers. It’s fair to ask whether queer students knew there would be resistance when they chose to attend a Christian university, especially one like Baylor with its conservatively worded statement on human sexuality. But students choose colleges for a variety of reasons. Sometimes their parents do the choosing. Some LGBTQ Christian students do want to be around classmates and faculty who share their faith—and hope to find affirming peers who can encourage them spiritually.

Baylor has set itself up for precisely this scenario. The university is known as widely for its Baptist roots as it is for its academic reputation and its nationally competitive Division I sports teams. That kind of wide appeal is only sustainable through tension, really. Whether it’s the reaffirmation of explicitly Christian language in school policy, or the refusal to enforce those policies through formal consequences, Baylor’s delicate balance is usually pissing off someone. In 1991 it became the center of a nasty fight between fundamentalist and moderate Baptists. The moderates, largely represented by the university administration, got what they wanted: independence from the Baptist General Convention of Texas. But as with many internecine fights, both sides would tell you more about what they lost, and how the soul of Baylor remained in peril.

In an August letter following news about Baylor’s exemption request, Livingstone tried to reassure students, saying the university remained committed to its queer community. Many seem ready to accept that there’s nothing to see here. The Lariat, Baylor’s student newspaper, published an editorial claiming the furor over the religious exemption was the result of bad-faith activism. Prism, a Baylor LGBTQ student group that gained its official charter in 2022 after eleven years of attempts, stopped responding to Texas Monthly’s request for an interview with one of its leaders. Matthey is the external chairperson of Gamma Alpha Upsilon, an LGBTQ student organization without official university status. Gamma is the more politically active organization of the two, but Matthey said few Gamma members have been motivated to push for repeal of the religious exemption. “Because this is such a vague topic we were going to have lots of students who don’t understand why this is an issue.”

But the issue is bigger than Baylor, where an emphasis on “Christian hospitality” might have a tempering influence on invocations of fire and brimstone. The belief that LGBTQ identities are demonic or punishable by death doesn’t always stop with a passing comment, Southwick said. In the name of salvation, queer teens have been subjected to conversion therapy and “gay exorcisms,” sometimes at the hands of Christian educational institutions.

This is why an in-house solution to addressing harassment is one of the greatest concerns among opponents to religious exemptions. At many religious institutions, morality, not justice, is the goal. Values such as “forgiveness” and “reconciliation” can put victims at a disadvantage, even in cases as serious as physical assault. At Hesston College, a small Mennonite college in Kansas, and Moody Bible Institute, in Chicago, victims were pressured to forgive their assailants and own their part in the “sin.” This sort of handling of rape can cast doubt on a college’s ability to handle verbal harassment in a serious way.

Johnson, Baylor’s Title IX coordinator, walked me through what an in-house reconciliation process for a harassment complaint might look like there. If someone files a complaint that doesn’t meet the criteria for a Title IX investigation, the university can convene an “educational conversation”—working with the offending student to help them understand why their behavior is problematic and, if appropriate, warning that if the behavior continues the student will be in violation of school policy. If the student who filed the complaint is willing to remain involved, they can pursue an “adaptable resolution process,” Johnson said, wherein both parties agree on an acceptable resolution. The message to offenders is, she said, “You’re entitled to a civil expression of your belief,” but it must be respectful. There’s no religious tenet that allows for harassing, degrading, or pestering behavior. “That’s not how you show Christian love.”

Koby Marsh had dreamed his whole life of going to Baylor. He also knew going in that, as a gay Christian man, he would encounter students who believed his sexuality was sinful. But he was still surprised in 2011, when he was an incoming freshman, and two prospective roommates asked to be reassigned after finding out he was gay. He called the student housing department and asked what could be done. He remembers the staff member assigned to his case asking Marsh if he knew Baylor was a Christian college.

“Yes, I’m a gay Christian,” Marsh replied.

He clearly remembers the staff member’s response: “That’s not possible.”

Marsh says the unwelcoming behavior escalated to include vandalism and threats of physical violence. Then, just after final exams in 2014, at age 21, he suffered a stroke after undergoing brain surgery. The stress of recovery and, he thinks, perhaps the brain trauma itself, left him unable to cope with what had become a consistently hostile social environment, he said. When filling out the paperwork to withdraw from school, Marsh listed harassment as one of the reasons, prompting a flurry of interviews with officials in various student-life offices. Administration members seemed to want to know if he planned to pursue legal action, he said. Later, when friends asked why he didn’t, Marsh said, “I didn’t think there was a point.” This was before Obama-era guidance extended Title IX to LGBTQ harassment.

Marsh finished his degree at the University of Houston, and eventually moved back to Waco, his hometown. He opened up a holistic healing shop, Grandaddy Willow, that sells crystals, salves, teas, and other purported remedies, both mystical and herbal. He’s surprised to see how much Waco has changed. His is not the only shop selling products that make rigid evangelicals a little nervous. The community in general feels more supportive of LGBTQ neighbors—there are more pride flags than many visitors might expect. He wonders if coming back to the place of so much wounding is “a God thing,” he said. Through it all, he sees healing, and marvels a little, even at his own faith. “I am still a follower of Christ, despite the things I went through at Baylor.”

Marsh’s story illustrates a problem Matthey and others have pointed out: Baylor has a terrible record of handling the various behaviors covered by Title IX—from harassment to assault. In 2015 a Baylor football player’s trial for sexual assault exposed a pattern of covered-up sexual misconduct allegations against athletes—the details of which were later deemed “horrifying” by the board of regents and “abhorrent” by the NCAA. Over the next two years more women came forward with reports of sexual assault—including gang rape—and subsequent coverups, in a cascade of lawsuits and investigations that led to the firing of head football coach Art Briles and the demotion and resignation of former university president Ken Starr. Baylor settled the largest of the sexual assault lawsuits on undisclosed terms with fifteen complainants in September. A month later another woman, Dolores Lozano, was awarded $270,000 after a jury found that Baylor was negligent in taking measures to prevent violence and had exhibited “deliberate indifference” to her reports of assault by a football player in 2014. With a new president, new Title IX coordinator, new leadership in the athletics department, and new rules regarding sexual harassment (such as extending enforcement off campus), the university says it is taking student safety more seriously.

The queer community, however, remains skeptical. It’s really about trust, Matthey explained. For a university that has maintained a strained relationship with its LGBTQ students, and a relatively recent history of egregious Title IX mismanagement, Matthey wonders why the university doesn’t go above and beyond what is required by law to demonstrate its commitment to its most vulnerable students.

- More About:

- Waco