The year is 2015, and J. P. Bryan is upset about President Barack Obama.

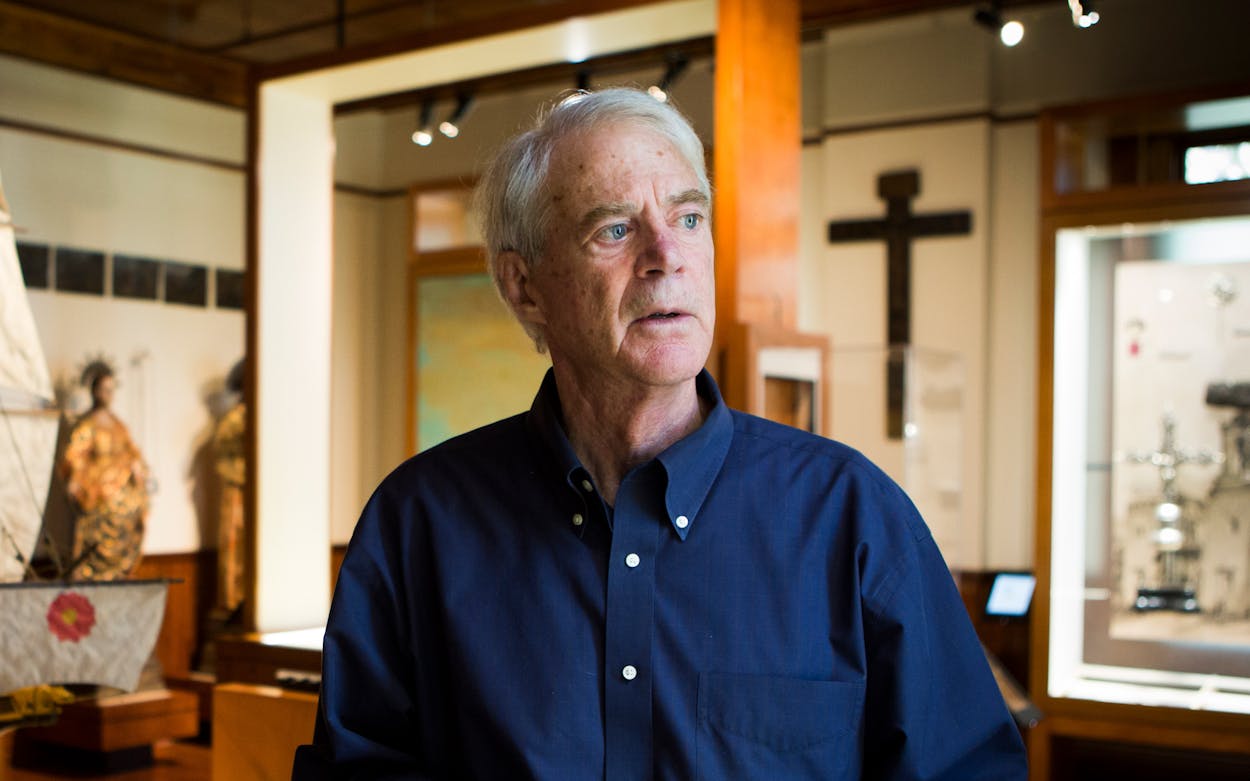

“I don’t know who he represents,” the then-75-year-old businessman tells me. We’re sitting at a mahogany conference table at the soon-to-open Bryan Museum in Galveston. I’m here to tour the building, which houses Bryan’s collection of 70,000-plus Texas historical artifacts, and interview its wealthy founder. But Bryan seems just as eager to talk contemporary politics.

“I really have never seen anything like it,” he continues. “I really think he has a totally different agenda from one that’s good for America. I think he either hates America, or he loves something else so vastly more . . . or he’s enamored with something that’s not America, that he’s going to promote it over us.”

“What could that be?” I inquire.

“I think it’s the Islamic world,” Bryan responds. “I think the guy is given to the Islamic faith, even though he went to, supposedly, a Christian church.”

“Do you think he’s a Muslim?”

“I think he’s a Muslim at heart, yeah,” Bryan says. “I think his whole faith system is very sympathetic to the Muslim world. . . . Look, our greatest ally is Israel. Why is he catering to the Muslims and offending the Israelis?”

Now, eight years later, Bryan finds himself embroiled in a bitter legal battle for control of the Texas State Historical Association (TSHA), a 126-year-old nonprofit that brings together professional and lay historians to “document and celebrate the state’s complex and diverse history.” The conflict pits Bryan—a deep-pocketed donor and honorary lifetime board member who was hired as TSHA executive director last fall—against board president Nancy Baker Jones and chief historian Walter Buenger. Both Jones and Buenger have charged Bryan with minimizing the role of slavery, racial violence, and white supremacy in Texas history. Hundreds of other members signed a petition that accuses him of using “divisive and racialized” language.

Bryan’s 2015 comments about Obama seem likely to fuel concerns about his racial attitudes. In April, after clashing repeatedly with Bryan over the organization’s ideological orientation, Jones called an emergency meeting to evaluate the executive director’s performance—and potentially fire him. In an apparent attempt to save his job, Bryan sued both the TSHA and Jones in state district court, arguing that the board was in violation of its bylaws. The judge granted a preliminary injunction preventing the board from meeting until the lawsuit is resolved.

The dispute ostensibly centers on whether the board is “balanced substantially” between academics and nonacademics, as its bylaws require. But at its heart is the question of how the association teaches and promotes history. Bryan has made no secret of his desire to steer the TSHA—publisher of the Southwestern Historical Quarterly and the encyclopedic Handbook of Texas—toward a more traditional approach that centers on the heroic role of Anglo settlers. In his June executive director’s report to board members, he accused the organization of “lurching so far to the left in our historical narrative” and presenting a “historical narrative that is offensive to a majority of our membership.”

Bryan recently told the Galveston Daily News that “the preferred narrative [of academic historians in the TSHA] is one that demeans the Anglo efforts in settling the western part of the United States for the purpose of spreading freedoms for all.” He has criticized Buenger, a history professor at UT-Austin, for describing the Alamo as a “symbol of what it meant to be white.” In a May legal filing, Jones argued that “Bryan is attempting a coup of the TSHA to whitewash its publications, events, and products to comport with his pro-Anglo ideology of Texas history.” An open letter signed by ten former TSHA presidents criticizes Bryan for glorifying the Anglo settlers, including his slaveholding ancestor: “Does Bryan seriously contend that his pioneer great-great-grandfather settled on his Brazoria County plantation with his thirty-eight slaves in order to secure ‘freedoms for all’?”

In a recent conversation with Texas Monthly, Bryan vehemently denied accusations that he is a racist. “I have helped plenty of Black people throughout my entire life, from the time I was just a young boy,” he told me. “I’ve given the eulogies at the funerals of three Black people that I worked with in my lifetime. I helped them build their church. I’ve spent the night in their homes, I’ve eaten at their tables. I love Black people. I worry about the little Black children in our neighborhood, and how they’re not being parented properly. And it concerns me deeply. I feel the same way about Hispanics—I’m proud of the Hispanics in our community. They are good family people, and they have faith, and they love their freedoms.”

Bryan explained that in 2015 he believed Obama was a Muslim “at heart” because of the president’s past association with Reverend Jeremiah Wright, the pastor at Trinity United Church of Christ, in Chicago. “Reverend Wright was spreading a message of hatred of America, and had an anti-American view in his message,” he said. “That was what I was reacting to, from what I had seen. Now, if President Obama says he’s a Christian, then I’m all in, I’ll believe it if he says it. I have no reason to doubt it. But I frankly haven’t seen where he has expressed his Christian faith.” He added in an email that he believed Obama was born in America and had “no question about the legitimacy of his presidency.” (Obama has expressed his Christian faith on numerous occasions, and has denounced some of Wright’s most controversial statements.)

The businessman said his views about Obama’s religion, and his right-wing ideology more generally, were irrelevant to the present leadership struggle at the TSHA. “What do my politics have to do with this?” he asked. “This is not a political issue, as far as I’m concerned. [My opponents] can talk about their politics all day long. . . . They can have any viewpoint they want about history or about politics. And you can never find one instance of me trying to censor or correct anything they said. I just want to make sure other people have the same opportunity they do to tell their version of history, their narrative.”

But some of Bryan’s critics say his belief in a conspiracy theory about America’s first Black president makes him a poor fit to lead the TSHA. Former TSHA board member Ben Johnson, a noted scholar of Texas history who teaches at Loyola University Chicago, is one of Bryan’s most vocal critics. “I think there is a direct line between what he thinks about Obama and what he thinks about Texas history,” Johnson said. “He thinks the United States belongs to people like him, people who are descended from white pioneers who moved west. And accounts that portray those people in a negative light, and dwell on things like slavery and racism and lynching, really bother him.”

Some prominent TSHA members told me that Bryan’s quotes don’t negate his decades-long financial support of the organization. Among Bryan’s supporters is former Texas land commissioner Jerry Patterson, who also advocates for a traditionalist view of Texas history; Patterson served on the advisory committee for the 1836 Project, which was created by the Legislature in 2021 to produce a “patriotic” version of state history that is distributed to new Texas drivers. Patterson called Bryan’s comments about Obama “inartful,” but praised his leadership of the TSHA. “We taught history wrong for about a hundred years—you know, ‘Anglo good, Mexican bad,’ ” he said. “So while the pendulum was too far in one direction for a hundred years, now at the Texas State Historical Association it’s too far to the left. It’s too ‘awakened.’ ” Traditionalists have criticized the TSHA for, among other things, beginning a 2022 board meeting with an acknowledgement that “we are meeting on the Indigenous lands of Turtle Island, the ancestral name for what now is called North America.”

Michelle Haas, a Corpus Christi–based publisher of Texas historical documents and right-wing blogger, told me that Bryan’s critics believe in ideas just as ludicrous as the notion of Obama being a secret Muslim. (Neither Patterson nor Haas believes Obama is a Muslim.) “There are scholars on the other side who would subscribe to the conspiracy theory that all of history is about white supremacy and oppression,” Haas said. “Is it true that Texas history has white supremacy and oppression and discrimination? Hell yeah that’s true. Is that the backbone of all our history? No, I don’t think it is.”

For the time being, the TSHA remains in limbo. A court injunction prevents the board of directors from meeting until the resolution of Bryan’s lawsuit, which could occur during a mediation session scheduled for August 23 in Austin. Bryan recently announced that the organization lacked the money to award several book prizes and research fellowships, calling into question its financial stability. Several of Bryan’s opponents told me that his efforts may end up destroying the very organization he claims to champion.

“I believe [Bryan] does honestly love the Texas State Historical Association,” said Kent Calder, who served as TSHA executive director from 2008 to 2014. “He’s been involved with it for many, many years. He could have brought people together. But he’s enlisted the help of all these culture warriors and right-wing trolls. It’s just very disappointing to me, and I think it spells the end of the organization.”

The only thing Bryan and his critics seem to agree on are the stakes of the battle. “How this whole thing goes will determine the future of the way the history of Texas is written,” Bryan told the Galveston Daily News in May. “That’s what it’s all about.”

Update, July 26, 2023: This story has been updated with an additional response from J. P. Bryan to clarify his views on Barack Obama’s presidency, and with an amended subhed that better reflects Bryan’s stated views on Obama’s Christian faith.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Barack Obama