This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The first squall line from Hurricane Allen appeared over Corpus Christi Bay early on Saturday morning. It was a seamless, sodden wall of cloud, and the weather that preceded it was stark and neutral, as if all its properties had been stripped away to stoke the monster storm behind it.

I was standing at the bay front in Cole Park watching the darkening sky and nervously fingering the keys to a rented car, a big gas hog that I was counting on to be reasonably stable in a hurricane. Like almost everyone else in the city I believed that Allen’s arrival was imminent and that it would hit the coast with the full force of its 170-mile-per-hour winds. Consequently I stood poised on the balls of my feet, ready to run for the car and head for higher ground. But despite all my apprehension I was enchanted by the oncoming storm. There was a foreboding lilt in the air, the waters of the bay were already lapping frenetically over the park’s miniature seawall, and no one was in sight except Action News teams and official functionaries in yellow slickers.

The wall of cloud moved across the bay, whipping up the water even more violently and depositing, in seconds, a half-inch of rain on the ground. I pulled the drawstring of my rain suit hood tight and planted my feet firmly against the wind, meaning to observe the finer details of the weather but unable to see past the raindrops pelting the lenses of my glasses. Finally I gave up and decided to move my car before it floated away.

From the car radio came the mirthless voices of meteorologists sternly advising citizens to stay indoors. The deejays, released from their routine, already addled from lack of sleep and perhaps frustrated at being sealed away from any real contact with the storm, sounded increasingly grave and periodically incomprehensible. “Complacency at this point in the storm,” one of them was saying, “does not have to be primordial.”

By early afternoon it had been decided that the eye of Hurricane Allen would pass over Brownsville, 150 miles further down the coast. After some deliberation I headed there too, emboldened by the notion that the roads would be submerged and I would have to turn around and come back.

Though there was a great deal of rain, the roads remained passable, and I found myself approaching Brownsville on a collision course with the hurricane.

I don’t know how strong the winds were at this point—maybe 70 miles an hour, strong enough anyway to pull trees right out of the earth and send them scudding along the ground dragging their root systems behind them. Out of the corner of my eye I would occasionally see a roof being pried off a house. The road was filling up with debris: lumber and highway signs and downed power lines. Several of the palm trees planted along the highway median had cracked and fallen over, but most withstood the wind, swaying with it while the foliage on top hung as limp as a rag mop.

In the open fields off the highway, horses and cows stood still with their backsides to the wind and their heads lowered, seeking shelter within their own bodies. A solitary dog skulked along near the shoulder, so drenched that the wind did not even ruffle his fur. He was miserable, and I thought about picking him up and taking him with me to Brownsville, but he looked as though he knew where he was going and I decided I would probably just interfere with his getting home. There were other dogs who seemed deliriously happy, roving in packs, running with the wind, and lifting their noses high to sample the strange seaborne smells that had been compressed into the hurricane and carried across half the world.

There was no doubt that the hurricane, at least the leading edge of it, had arrived. All the radio stations were out except one, and as I drove closer to Brownsville the announcer sounded as if he were on his knees beside his console, praying for deliverance. He was in any case invoking God and attempting to instill in his listeners a warm glow of doomsday solidarity. It was all beginning to make me nervous. I could see that the storm was not as bad as the reports the announcer was being given by his field correspondents—who were, like all the other media people down here, as delighted to be frolicking in the hurricane as the dogs on the side of the road—but it was bad enough.

In Brownsville I drove to a newly opened Red Cross shelter at Texas Southmost College, which was about three blocks from the International Bridge. The shelter was a brand-new classroom building, and there was a Red Cross volunteer standing at the entrance who greeted me as courteously as a doorman.

The electricity had gone out, and though it was still daylight outside, the halls of the classroom building were so dark that one needed a flashlight to get around. The winds were 80 miles per hour now, someone said. Down the street the revolving sign on a hamburger stand spun incessantly, and the bright red roof of a self-service gas station rocked back and forth as the wind worried it loose from its mooring.

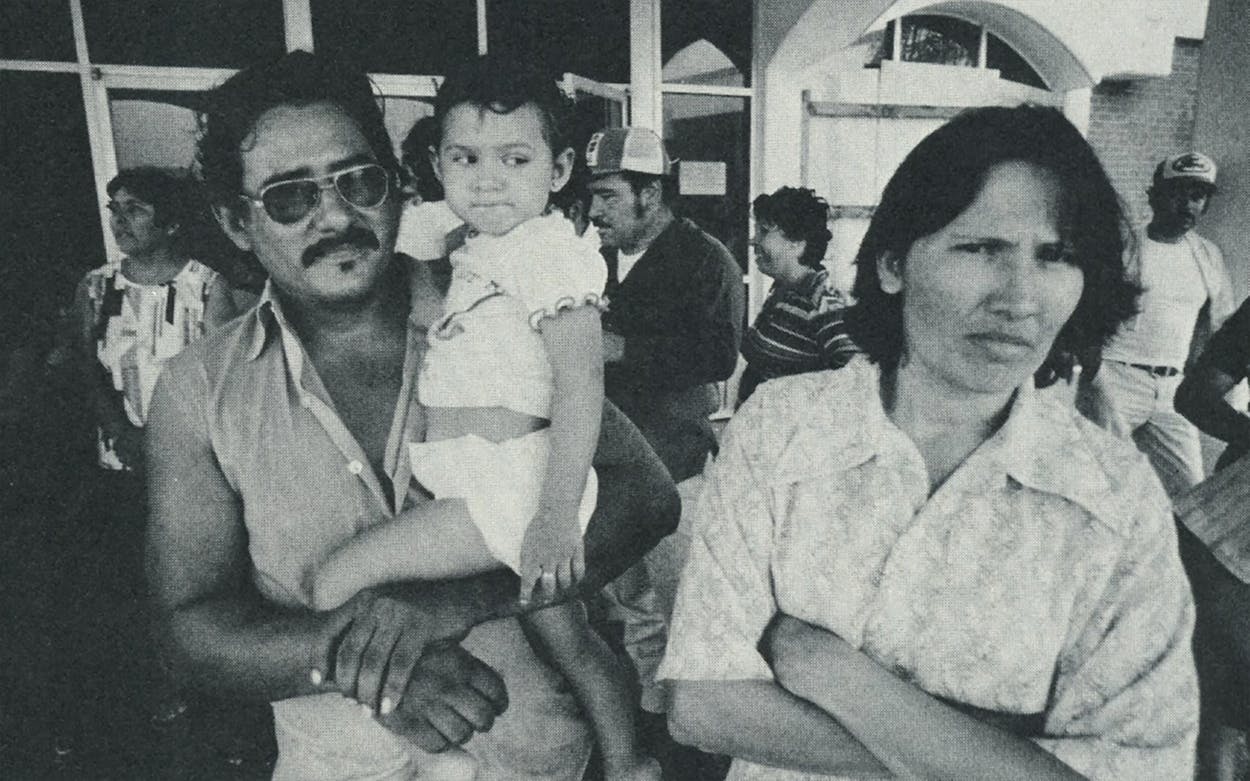

Every few minutes a car would drive up, and we would run out into the storm to help its occupants into the shelter. The refugees were all Mexican Americans who had thought their houses could withstand the hurricane until it started bearing down on them in earnest. They brought along ice chests and clothes packed in cardboard boxes that as often as not disintegrated in the rain as we carried them across the wide lawn to the building. The families were not outwardly afraid, but without exception they were silent once they reached the security of the foyer, and this silence was reflected in the dark hallways and classrooms and auditoriums of the shelter, so that the whole place was as quiet as a church.

As the evening wore on the refugees arrived steadily, occasionally driving their own cars but more often transported in National Guard trucks. Finally there were a couple of hundred people in the shelter. The building quietly absorbed them all, and there were still unoccupied classrooms branching off from the long hallways.

A group of us stood outside waiting for the trucks and watching trees on the campus topple over one by one. We were screened from the wind by the edge of the building, so that our space was as calm and safe as the eye of the hurricane itself. I felt detached and lazy. A few civilian cars still cruised down the street under precariously rooted light poles and trees.

“I can’t believe guys are driving around in this,” one of the volunteers said.

“Hey, man,” someone answered, “it’s Saturday night.”

The eye of the hurricane had begun to stall in the Gulf, and so there was a certain stasis in the intensity of the outer edge of the storm. At ten o’clock the radio said that Allen had remained nearly stationary for the last two hours and its strength had decreased considerably. Still, everyone thought the worst of it was yet to come, and they settled in for the night. A mother walked her baby down the hall, trying to get him to sleep, but except for his mewling there was hardly a sound among the two hundred people in the building. I lay down on the floor and fell instantly asleep but was awakened a few hours later by a man and woman at the registration desk talking fervently about their divorces and the nature of love and family responsibility. I waited until they had exchanged phone numbers and then stood up and took a look outside. It was pitch-black, but I could hear that the wind had slackened.

When the hurricane started to move again it was frayed and weakened. It was heading north now, up the Laguna Madre, and was expected to cut across the coast somewhere near Raymondville. There was rejoicing in the wee hours on the radio.

By daylight it was almost calm outside, but the weather still had a charge to it. Driving north back to Corpus I noticed that the hurricane had destroyed mobile homes and fruit stands and pulverized at least one roadside curio shop, strewing velvet paintings and plaster donkeys and other Mexican lawn ornaments up and down the highway.

The cotton fields west of Corpus were submerged, a vast, muddy lake that stretched for miles. The hurricane had passed very close to the city and the water had come up over the seawall, flooding Shoreline Drive and seriously damaging North Beach, the unprotected stretch on the other side of the Harbor Bridge. But compared to what had been expected, and what had been delivered in the past by Carla and Celia, the overall effect of Allen appeared slight.

The weather remained overcast and drizzly but hardly violent at all. But until late in the day the media kept urging people to stay in their shelters. Some of those people had been holed up in elementary schools with nonfunctioning toilets for three days, and it began to seem that the radio and TV stations wanted everyone to stay indoors just so they could prolong the drama of the event and not be exposed.

The place where I had been standing the morning before in Cole Park was now underwater, and it looked like the little seawall there would need to be shored up when the waters receded. The damage to buildings was superficial, except in the case of superficial buildings, whose residents had lost everything. Hurricane Allen had turned out to be a minor storm, but its burden of grief and annoyance had not yet begun to be reckoned. It was far inland now, spawning tornadoes, losing definition, at the mercy of the elements it had once held in thrall. I had the feeling that the storm had not only missed those of us who waited in its path but had eluded us as well. We had anticipated it, braced for it, and in some perverse, primitive way even hoped for a demonstration of its natural power. But it had its own course to follow and it took no notice.

- More About:

- Weather

- TM Classics

- Brownsville