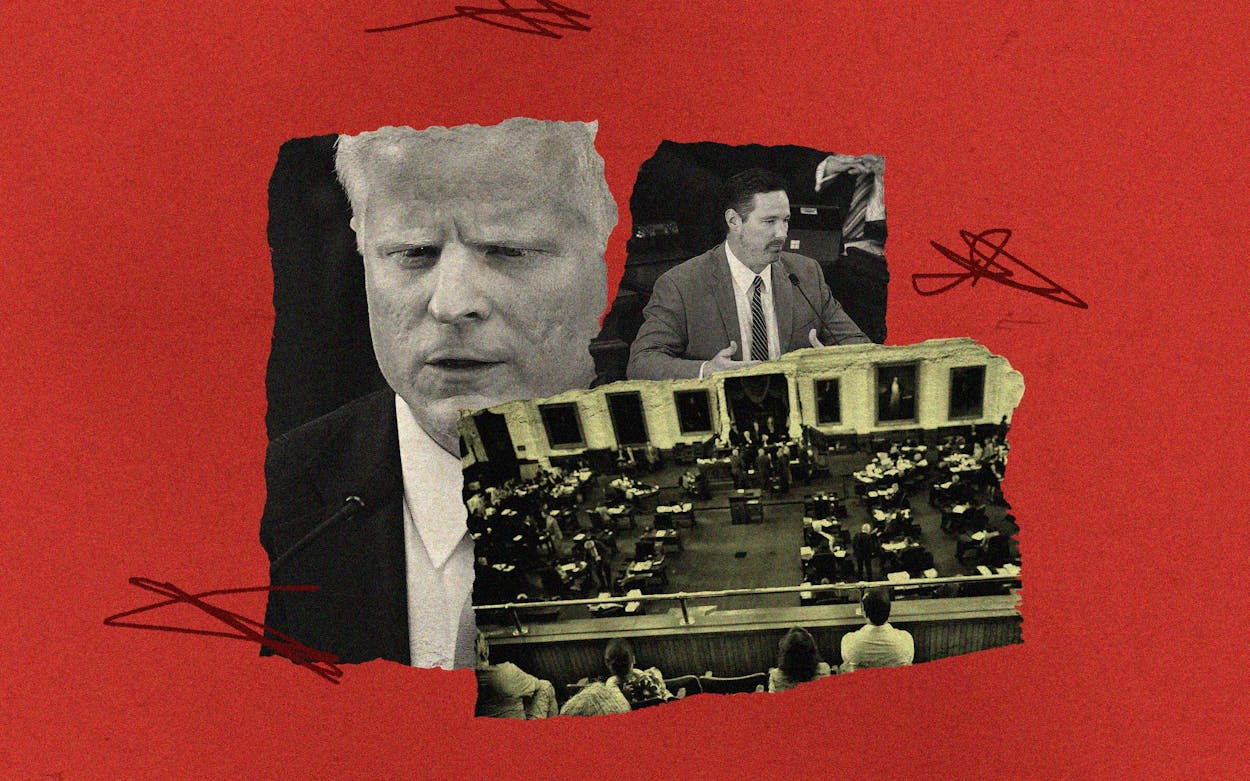

Thursday, day eight of the Ken Paxton impeachment trial, was a day that left many longing for the fireworks of Wednesday’s events in the Texas Senate chamber. The public gallery was virtually empty except for the seasonal invasion of crickets (find your own metaphor) and some mildly curious visitors that included the wife of Republican state representative Briscoe Cain of Deer Park and their five well-scrubbed children who seemed deep into their homeschooling homework, perhaps because it was more compelling than the testimony. (Dad came upstairs just before the break to escort his brood to the elevators.) There was a toddler, part of another group, who tumbled down a few gallery stairs but managed to right herself without an outburst before the proceedings began. Another child did not, and so was publicly ejected by eight-time grandpa, and judge in the impeachment trial, Dan Patrick. Mom flounced out in a huff with her stroller, swerving like a driver in the Indy 500.

Patrick may have spared her a morning filled with torpor as the defense began presenting its case—after getting its expert witness tossed by the prosecution. The first witness, then, was Justin Gordon, who works for the OAG as head of the open records division and could quote code sections of the law with mind-numbing accuracy—or at least no one had the nerve or desire to challenge him.

Gordon was questioned by senior attorney Allison Collins, the first woman to appear for the defense team, who along with several colleagues is on leave from the AG’s office to defend Paxton. There was a whole lot of hoo-ha about how the open records department normally works—but then we got to a particular file.

That file in question—the one compiled by the FBI in its investigation of Nate Paul—was requested by Joe Larsen, a lawyer for Paul. Paxton called Gordon into his office for a discussion of the file, Gordon testified, but did not pressure him to release it. However, under cross, Gordon said this was the first time Paxton had ever involved himself in an open-records request. It appeared to be another example of the AG intervening to the benefit of Nate Paul. Score: prosecution 1, defense 0.

Next up was the white-haired, dapper Austin Kinghorn, the associate deputy attorney general for legal counsel at the OAG’s office. When Chris Hilton, another lawyer on leave from the OAG’s office to aid in Paxton’s defense, asked about his politics, Kinghorn said that on a scale of one to ten, he rated his level of conservatism an eleven; when asked if he were a Republican in name only, he demurred by saying, “I’ve been called a lot of four-letter words but that’s not one of them.” The main thesis of his testimony was that the attorney general really could do whatever he wanted—like hiring Brandon Cammack as a special prosecutor without going through channels. In fact, in Kinghorn’s mind, that was a good thing.

During cross-examination, Erin Epley asked Kinghorn about some of their previous conversations, and Hilton made another one of the defense’s ubiquitous objections, which he labeled as hearsay but whose clear purpose was to prevent damaging information from being presented. Epley was flummoxed: “I don’t know what to say about that, your honor. We are both here.” Things got worse when Epley pressed him on his legal and ethical responsibilities.

“Who do you think your client is?” she asked.

“My client?” Kinghorn asked, confused. The answer was obvious. His client was “the attorney general.”

Epley disagreed. “Your client is the State of Texas.”

I was starting to wonder why the defense had bothered to put on a case. The next witness, dark-haired, bearded Henry De La Garza, director of human resources for the OAG, did nothing to assuage my concerns. He testified that the termination of various whistleblowers—the ones not driven out—was warranted. (He used the HR-friendly euphemism ”involuntary separation” instead of “ fired.”) De La Garza attributed their issues of “insubordination” and “unacceptable tone” to “having a new boss.” That would be Brent Webster, who replaced first assistant attorney general Jeff Mateer, who had resigned after going to the FBI to express his concerns about Paxton. De La Garza had no firsthand dealings with these insubordinates, however, and instead testified, “As HR director I have to rely on information that is presented to me.” (It was presented by Brent Webster.) Hence, De La Garza rubber-stamped the involuntary separation of previously loyal, highly rated staffers without doing any homework on his own, according to his own testimony.

The cross-examination by prosecution attorney Daniel Dutko was, again, an opportunity for visitors to take cover under the tiny, cramped, gallery seats. Tall and thin but with a towering tone, Dutko began by asking whether the OAG might have had a “Brent Webster problem” instead of some high-ranking staffers with bad attitudes. Then Dutko reminded the senators (and the witness, of course, the one from HR) that whistleblower law holds that an employee cannot be terminated until ninety days after blowing the whistle, in this case by going to law enforcement. These guys, in contrast, were in some cases involuntarily separated within . . . a month.

Then there was Grant Dorfman, a loquacious deputy first assistant attorney general, whose conservative bona fides include participating in Paxton’s election-challenge lawsuit. His main purpose seemed to be to describe—at great length—how great things were going in the AG’s office. He proudly cited CNN’s claim that Texas was the legal graveyard for Biden policies. But by showing how hard the AG’s office worked to settle the case—“to save the taxpayer’s money,” he claimed—Dorfman also showed that the office, well, agreed to settle with the whistleblowers. This move appeared to be another example of Paxton’s tendency to see that negative information stays buried.

Cross was another disaster for the defense. Dorfman admitted that he never investigated the whistleblowers’ claims himself. “I had no personal knowledge of what happened,” he said.

And then the defense rested. Not a moment too soon.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Ken Paxton