John Leventhal is one of the most important record producers working in Americana music today. But the eloquent New Yorker, who’s also a hit songwriter and virtuoso guitarist, readily acknowledges that placing his collaborations in that catch-all genre doesn’t tell you much about how they actually sound. To make that determination, you’ve just got to listen. You could start with the rootsy groove of his wife Rosanne Cash’s 2014 album The River and the Thread, which earned the two of them three Grammys. Or the Southern soul of his 2016 album with Stax legend William Bell, This Is Where I Live, which also won a Grammy. Or go all the way back to his first big splash, Shawn Colvin’s 1997 album A Few Small Repairs and its ubiquitous pop hit, “Sunny Came Home.” Though the three records may seem distinct stylistically, they all share a common sonic trait: None of them sound dated, not to the time of their old-school influences, nor to the years they were made. They sound, in a word, timeless.

Subscribe

(Read a transcript of this episode below.)

That’s Leventhal’s goal whenever he goes into a studio, and on this week’s episode of One by Willie, he discusses a record he considers a glowing example of that feat: Willie’s career-making 1975 hit, “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.” It was the first song that clued Leventhal in to the genius of Willie, a recording that he says has yet to show any age and almost certainly never will.

From there he’ll get into his session work with the hall-of-fame players that backed Willie on his pivotal 1993 album, Across the Borderline, plus the reasons he considers Willie a cross between legendary Nashville guitarist Grady Martin and Pablo Picasso, and his own late father-in-law, Johnny Cash, a cross between Elvis and Abe Lincoln. And then, keeping with his thesis on defying the constraints of time, he’ll touch on three giants—Willie, Paul Simon, and Bob Dylan—who’ve never quit pushing themselves toward new sounds and ideas, even after six-plus decades in the business.

It’s a lesson that Leventhal has taken to heart. Earlier this year, at the tender age of 71, he released his first album under his own name, Rumble Strip. It’s a collection largely of instrumentals, marked by his precise yet soulful guitar picking that reveals him to be a spiritual heir of another of his heroes: the great Chet Atkins. Consider it a masterful debut from a promising new solo artist.

We’ve created an Apple Music playlist for this series that we’ll add to with each episode we publish. And if you like the show, please subscribe and drop us a rating on Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts.

One by Willie is produced and engineered by Brian Standefer, with audio editing by Aisling Ayers and production by Patrick Michels. Our executive producer is Megan Creydt. Graphic design is by Emily Kimbro and Victoria Millner.

Transcript

John Spong (voice-over): Hey there, I’m John Spong with Texas Monthly magazine, and this is One by Willie, a podcast in which I talk each week to one notable Willie Nelson fan, about one Willie song that they really love.

The show is brought to you by Still Austin craft whiskey.

This week, six-time Grammy winner John Leventhal, a virtuoso guitarist and one of the leading Americana record producers, talks about the 1975 song that broke Willie’s career wide open:“Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.” Now, casual music listeners will probably know John best from two iconic nineties pop hits that he had a huge hand in, Marc Cohn’s “Walking in Memphis” and Shawn Colvin’s “Sunny Came Home,” as well as his collaborations with his wife, Rosanne Cash, like her landmark albums The Wheel and The River and the Thread.

But with us he’s gonna focus on “Blue Eyes,” the song he says first clued him in to the genius of Willie, before describing what it was like to be a young picker working with Hall of Fame session players on Willie’s pivotal 1993 album, Across the Borderline, and then explaining why he thinks of Willie as a cross between Grady Martin and Pablo Picasso, and his late father-in-law, Johnny Cash, as a cross between Elvis and Abe Lincoln.

So let’s do it.

[Willie singing “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain”]

John Spong: Where we start is, what’s so cool about “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain?”

John Leventhal: Well, when I was approached about doing this, of course, it’s like choosing my favorite of any artist that I’ve been moved by, it’s always challenging. I’m not really wired to have favorites, it’s kind of all in the stew. But I realized, and for a minute, I was going to pick “Three Days,” because—

John Spong: Oh, nice.

John Leventhal: . . . I just kind of love that song. It’s just a great Texas, Ray Price shuffle. But it’s got a cool twist on it, both musically and lyrically. But then, when I went one step deeper, I realized that the Red Headed Stranger record, and this track in particular, is really, if I look back, is what introduced me to Willie. And so it had, in some ways, the most direct and visceral impact on me, because there was a lot of things going on about it. It was like, correct me if I’m wrong, ’74, is that when this came out, ’74, ’75?

John Spong: ’75, yeah.

John Leventhal: Yeah, yeah. So I had literally just made my first steps toward even thinking about becoming a musician. And I remember hearing it for the first time, and not really being aware of Willie. Because I grew up in New York, went to college in Madison, Wisconsin. And I already loved country music, what I had heard, but I hadn’t dialed in Willie yet. So this was sort of my introduction, because it was a hit. It was a hit on the radio. And I really, I remember being struck by it, like, “What is this?” Because it was being played on a country station, but it wasn’t, like, overtly country, and it wasn’t really like anything else that I had heard. It was stark. It was raw. It was underproduced. It felt sort of haunted to me, and I’ve always been drawn to kind of haunted ballads, in particular. I realized later that it’s definitely in this kind of stream of this kind of, what I would call haunted Appalachian . . . African-Appalachian ballad tradition that I love. And my feeling for that album, and that track, have not diminished in fifty years since then.

John Spong: Wow.

John Leventhal: Because I had to go back and listen to it. I hadn’t actually listened to it with, quote-unquote, “critical ears” in a long time. I was still struck by how unbelievably direct and simple, with no artifice . . . In some ways, it’s the purest statement of Willie. It distills stylistically, so many things about him. His guitar playing. There’s hardly anything going on. It’s his guitar, a bass, and I guess Mickey comes in a little bit, right?

John Spong: Yeah.

John Leventhal: There’s no drums, there’s no production. And your die-hard Willie obsessives will correct me, I’m sure you’ll get emails about it, but I think maybe this is the first time he’s the producer? It’s the first time he’s totally committed to his band. It’s the first time he’s totally committed to that sound, which we’ve now become used to. So to me, it’s like that first statement is still powerful. Like I still love Meet the Beatles, sort of for the same way.

It’s the thing that gets into your . . . For me, the thing that got into my DNA in the beginning, and once it gets in the DNA, it’s hard to let it go. And I mean, I’ll keep droning on. There is one other thing about it that I loved, and it kind of turned my head around because I was just starting to be a musician. I didn’t know anything, let’s put it that way. I had maybe done a handful of gigs. I was learning about harmony. I was learning about how to play in a band. I was learning everything. And it had . . . Me and my friends were struck. It was like the first time I heard Willie sort of use unusual chord changes, that you had never, ever heard in a country song before. In the solo, all the musicians I knew, and I have a guitar here . . .

John Spong: Yeah.

John Leventhal: Shall I play them, right? So he’s going, I won’t pretend to play like Willie, but it’s whatever the— [guitar playing] “In the twilight’s da-da . . .” those chord changes, they kind of flipped me out. I was like, “What is that?” I didn’t know what that was. And so of course, what it is, is it’s pulling from a certain jazz harmony tradition, which I was just starting to learn about. But the fact that he had conflated all this together, this kind of ballad tradition, this haunted thing, clearly a country sensibility, but there were these jazz changes in it. And he had a very, very direct, stylistic voice, both as a singer and as a guitar player. It really impacted me. So that’s kind of why I chose it. I could have probably chosen other things on the record too, but I thought “Blue Eyes,” even though he didn’t write it, was in some ways the most powerful distillation of this thing I’m talking about. It’s pure Willie. It’s never gotten better. It’s gotten different, but for me, it’s never gotten better. So there you go.

John Spong: The thing is, it’s an explosion. The album clearly is sound throughout, and consistent throughout, but this is the introduction. And as you say, not just to the record, but it is the introduction, when you hear it on the radio first, but also to Willie as the mature artist, in a sense.

John Leventhal: For a lot, particularly a New Yorker like myself, right? Because we weren’t going to hear anything prior to that. No one was going to tell me that he had written “Crazy” or “Nightlife” or any of these things. Nobody was around to hip me to that, and so it opened the door.

John Spong: Because you’ve described so well what that recording of Willie sounds like, and because we all know it by heart, can I zag rather than zigging here? Can I play for you the Roy Acuff version, the one that Willie would’ve heard as a kid?

John Leventhal: Sure. Yeah. Let’s do that.

John Spong: Because it’s the one that made him fall in love with the song.

John Leventhal: I love it.

John Spong: Because then you’re kind of just getting to the song itself, and not even Willie’s performance of it.

[Roy Acuff singing “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain”]

John Leventhal: It is a fairly happy version of a sad story. Well, I think they were at cross purposes. That’s to get people up on the dance floor. And Willie’s was to tear your heart out with a kind of timeless sense of loss and sadness.

John Spong: Well, that’s the thing, because there’s a verse in that version that Willie excised.

John Leventhal: Yeah. But it is funny to hear. I was like, “Oh my God. Yeah, there is another verse.” And it’s the saddest of all the verses, but that was pretty happy.

John Spong: Right. But it also pulls it out of the story, because Roy Acuff is singing about someone he misses, but not necessarily someone he killed.

John Leventhal: Yeah, no, it’s true. Yeah, it’s true. Yeah. Oh God, that would’ve been horrible if they sang the whole song, just like a murder ballad. “Yeah, but I had to kill her. I miss her. But Lord, I had to kill her.”

John Spong: “But she had it coming.”

John Leventhal: Yeah.

John Spong: We’re glad we moved on.

John Spong: But also, that would have jacked with it a little, anyhow. It doesn’t need any more than Willie kept in here. I mean, this song is poetry. “In the twilight’s glow I see her / Blue eyes crying in the rain.” Man, what a great first line.

John Leventhal: Yeah, really is. It’s a great song, great song. And like I say, one of Willie’s best, in my opinion, one of his best performances all the way around, as a singer and a musician, and a producer, and an arranger. I mean, to choose to do it so starkly means—it does something that, in the back of my mind, I’m sure I’m not even remotely successful at this, but in the back of my mind, I’m always thinking about when I produce records: I hate the idea of anything I do getting pegged in the time that it’s being done.

So for me, the fantasy or the goal is, or the aesthetic sort of dream, is if you record something in 1974, it would’ve sounded great in 1964, 1994, 2024. It won’t reek of the moment it was recorded. It’ll just feel slightly like it’s always been there, and it always should have been there. Now, that’s kind of highfalutin, but that is kind of a thing that I think about a lot. So that’s probably another reason I picked this album and this track, because it’ll always sound great. It’ll never sound dated. It’ll never sound pegged to the moment it was recorded. It’s not dependent on technology or current trends or current sounds, or anything like that. So yeah, pretty high art for me. For a popular song, pretty high goal.

John Spong: When I talked to Dave Cobb, who, of course, is a producer, about another song on here, all he wanted to talk about was what he called the “beautiful, barren landscape.”

John Leventhal: Yeah, yeah. I would call it . . . “stark and haunted” are the words that I like. “Barren” sort of has another connotation.

John Spong: Yeah. Well then let’s listen to Willie’s version.

John Leventhal: Why not?

[Willie Nelson singing “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain”]

John Leventhal: Yeah, man, it doesn’t get better than that. And also, there was one other element to it that I realized that really struck me at the time, and has only gotten more noteworthy as the decades have gone by, is Willie’s utterly unbelievable and completely eccentric sense of time and rhythm when he plays guitar. It’s really extraordinary. I had the honor of mixing Dr. John’s last record. Mac Rebennack’s last record was made as he was sadly dying. And he does a duet with Willie on it, of “Old-Time Religion.” And it’s great. I don’t know if you’ve heard it, it’s really good.

John Spong: Uh-uh.

John Leventhal: Yeah. But I had to—I hope I’m not letting the cat out of the bag. Willie took a few solos on it, so I wasn’t at the sessions or anything, I’m mixing the record. And I had to sort of cobble together the best solo. And yeah, it was wild. It’s like where he’s placing the notes in some ways makes no sense. And then you actually put it in the context of the song, and it’s brilliant, right? It’s just otherworldly, completely remarkable what he’s become as a guitar player. It’s really. . . It’s like, what is the . . . Grady Tate meets Pablo Picasso or something? I can’t even think. Not Grady Tate, Grady Martin, the great Nashville session player. Grady Martin and Picasso in one statement, it’s kind of amazing.

On that track, we’re starting to hear the development of his statement as a player as well. It’s really incredible for such a concise and incredibly simple record and performance.

John Spong: Yeah, yeah. Yeah, it’s interesting. And a lot of times, when people tell the Willie story, they like to, especially as simplified as it gets sometimes, they like to paint Chet Atkins as some kind of villain in the piece, or something like that, like he did Willie wrong. And no, I don’t buy any of that.

John Leventhal: Chet was great. He was just a realist, that’s all. Yeah.

John Spong: Yeah. But I have read that he wasn’t the biggest fan of Willie’s playing, but Willie wasn’t playing as well, at that point, as he came to. But also, it’s a very different style. I mean, Chet Atkins is the most precise, one of the most precise guitar players you’ll ever hear. And to your point, Willie, sometimes it’ll be as subtle and as few notes as what we just heard, but every one placed exactly right. And then sometimes it’s flurries, and it’s just a bigger deal. It’s a very different kind of—

John Leventhal: Yeah, it is.

John Spong: Less orderly. Less orderly, maybe?

John Leventhal: It is. Well, what is the biggest statement you can make as an artist, as a musician? As kind of every genre and every style has been sort of overworked and overdone, and turned into a product. And we’re beaten over the head with everything, particularly guitar-wise.

I mean, to me, the biggest accomplishment you can have is to create a unique style that’s you and utterly you, in which people recognize it in the first few notes, both as a singer and a guitar player. And Willie’s certainly done that. And it carries emotional weight. It’s not gimmickry, it’s an honest distillation of what he’s trying to accomplish as an artist. And to me, that’s the goal. To me, that’s the goal. That’s the end of the goal. It’s not like, “Can you go ‘ba-di-di-di-di.’ ” I mean, that’s great, but it’s only great if it’s in service to something deeper and more meaningful. So I think Willie has done certainly what I would like to do, to really develop into [having] a compelling style that’s my own, on every level, as a producer, writer, musician, whatever.

John Spong: So if this is the record that introduces you to Willie, kind of like as you’re starting on this career, this life of art, music—what Willie comes next? What’s the evolution of your appreciation of him, and how does that change as you develop all this musical experience yourself?

John Leventhal: Oh, well, I’d have to think about that. Well, I mean, then he starts to have hits. I mean, then you can’t get away from the guy! Well, then it explodes, right? Because that’s kind of when country music, in a sense, goes national, right? And so you have commercial country AM stations in New York City, and I’m listening to it in my car. That didn’t exist in the sixties and the early seventies, right? I forgot, I can’t remember the name of the station, but I think it was like 1040 on the AM dial. Yeah, and then he just starts to have hit after hit after hit. I mean, I think the next record that, certainly, that I truly, truly loved . . . Like, all the outlaw stuff, I mean, I liked it all. It didn’t quite hit me in my deepest place. But the record he made with Booker T., the Stardust record, is off-the-charts brilliant.

That’s just one of those records, you can’t find a person who doesn’t like that record. It’s like that’s a little miracle in and of itself. You would have to really gin up, or jack up, some kind of hostility to not like that record. It’s just so elegant and simple, and once again defines another thing. We used to make fun of it, but in a really awestruck, respectful way, which was . . . because they were jazz standards, and so at that point, I’m paying attention to jazz. And I’m trying to learn about jazz harmony, and I’m listening to Charlie Parker and Miles and Wes Montgomery, and I’m trying to get a little of that under my skin, which was good. And Willie and Booker had a different take on the, quote-unquote, “Great American Songbook.” We used to call them the Willie Nelson chord changes.

What are the chord changes to this tune, or what are the chord changes to “Stardust?” Are we going to do the real book chord changes, like the legit changes? Or are we going to do the Willie changes? Which were great, but they were informed by an earthier tradition, the Southwestern swing, dance band tradition, or whatever his tradition is. And they distilled it into a simpler way, and it’s just utter perfection. There isn’t a false note on that record. That is a brilliant record. Now, whether that’s Booker or whether that’s Willie, or just the two of them together and the chemistry, I don’t know. But man, that is a great record. Just unbelievable.

John Spong: It’s perfect. It’s perfect. How bad a day would you have to have to talk s— on that record?

John Leventhal: No, you really can’t.

John Spong: To not have . . . [to have] that record not help.

John Leventhal: No. And you remember, it was huge. It was as big as Sgt. Pepper’s in its own way. It was just gigantic.

John Spong: It was the biggest seller of his career still. By a large margin. And it was on the charts for ten years. And the legend’s out there, the label tried to talk him out of it. They said, “Are you kidding? Do ‘Luckenbach, Texas’ again. You can’t do this.” And it was, in a real sense, the beginning of, well, rock . . . country, but also rock stars, too . . . Once you get to a certain point in their career, everybody does an American Songbook record now. Once upon a time, it was Ella and the jazz artists, but Willie kind of opened the door for the rest of Rod Stewart’s career down the road.

John Leventhal: Yeah. Oh my, Willie’s take on it is so much hipper, God, than Rod Stewart’s. Nothing . . . sorry, Rod, love all your early records.

John Spong: I adore Rod Stewart.

John Leventhal: Yeah, I like to. . . . Yeah, but it’s just corny when he does it, to me. It’s like it’s just overworked cliches, but Willie brought something fresh to it. I mean, I’ll be honest, I’ve thought about doing a version. I don’t know, I’d have to see if I could talk my wife into it, or somebody. Like how to take the tunes coming from the Jerome Kern–Gershwin–Richard Rogers tradition, how do you do that and make—I hate to use the word “country,” because it’s kind of meaningless at this point—but how do you take a rootsier sensibility, informed by all the rootsy streams of American music, and overlay it onto that, and have it feel real and not gimmicky, and soulful and timeless and all that? I’ve thought about doing that. How do you sort of take the instrumentation, for example, of country music, and create something new and different with those tunes? Which are unbelievable tunes, right? They’re just unbelievable.

John Spong: Yeah. Yeah. Boy, I would listen to that record if y’all did that. There’s so many songs in the songbook. Like, Willie goes back to—he’s done so many of them, but—

John Leventhal: It’s endless.

John Spong: It’s not a blind spot—there’s just these songs that don’t turn him on, and so there’s a whole bunch he hadn’t touched.

John Leventhal: And you wouldn’t necessarily have to handcuff yourself to the musical—because most of those songs are coming from musical theater tradition. They weren’t really, for the most part, being written to be hit songs on the radio. They’re coming from musical theater that singers then take and record, right? But you could expand it beyond that, to great songs of the sixties or seventies, and kind of reimagine them in the spectrum of what this thing I’m talking about. Anyway, la-di-da, I could talk about this stuff forever. I have to convince one Rosanne Cash, and see if she wants to do it. I don’t know.

John Spong: Well, you’ve got a bonus vote now, here.

John Leventhal: Okay.

[Willie Nelson singing “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain”]

John Spong: Well then, to Across the Borderline then, which is Willie’s album that Don Was produced in ’93. How did you get involved in that?

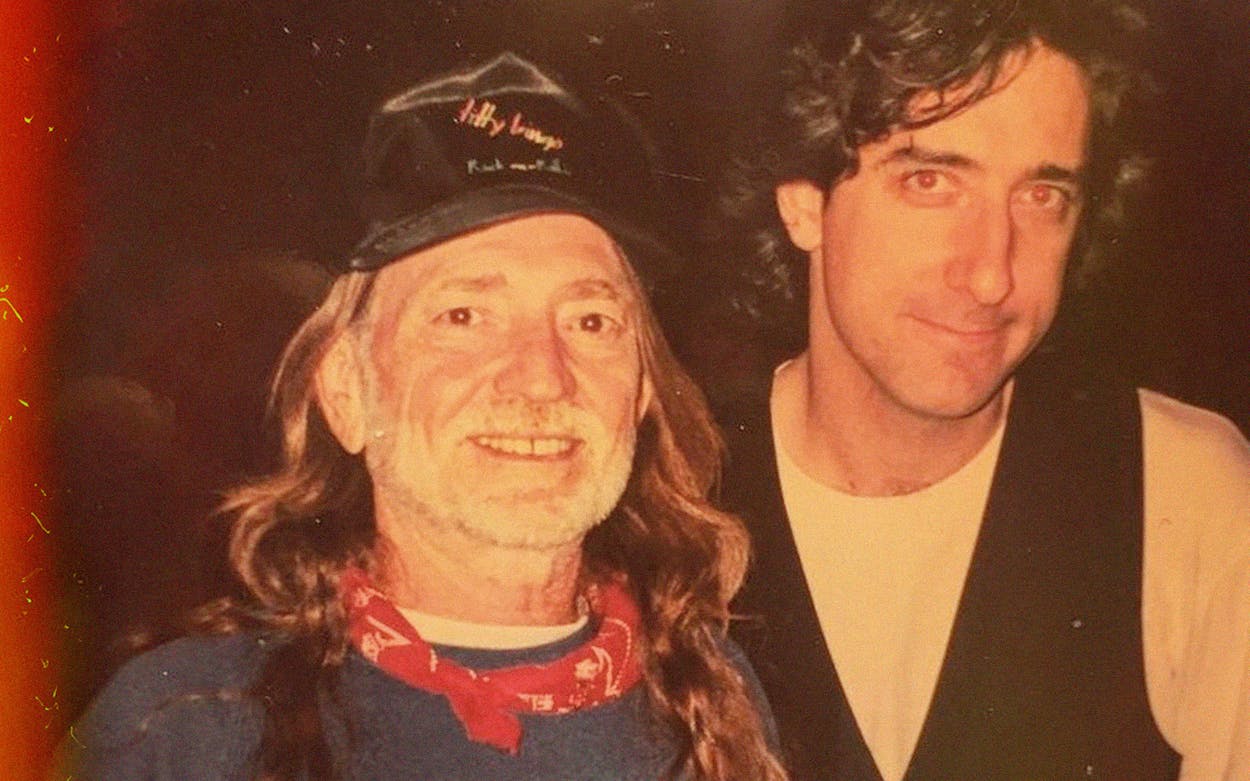

John Leventhal: I don’t remember. But I mean, Don just—my memory is Don just called me. That they had done half of it in LA, I think, and that he brought the band that he had out there to New York. And he called me and said, “Hey, you want to come bring a couple of guitars, and come to the Power Station,” where they cut it, and I was the only New Yorker. It was kind of wacky. But you know, man, it was amazing on a lot of levels, because I walk in, I didn’t know what to expect, honestly and truly.

First of all, it was very nice of Don to ask me, because it was still kind of relatively early in my. . . . I had just started to kind of click as a producer. I’d won a Grammy, and sort of had some luck as a songwriter with this guy, Jim Lauderdale. And I’d just met Rosanne, so things were just . . . Oh, and I’d arranged this “Walking to Memphis,” for Mark Cohn. So it was just my thing, my star was . . . ”my star!” I don’t think I’ve ever referred to my career as “my star.” That’s a first, folks. “My star was starting to rise!” So it was nice of Don to ask me.

John Spong: I almost spit water onto my laptop just now, but that was because of your reaction, not mine.

John Leventhal: But he invited me. But I walk in, and it’s so many musicians who I love and admire. I think I had worked with Keltner. Keltner was on it, Jim Keltner, a drummer, great drummer. And then one of my guitar heroes, like really, truly, Reggie Young, who I just can’t speak more highly of. It started a very sweet and lovely relationship that I had with Reggie. And I just admired him so much. Oh God, Paul Franklin was on it . . . Benmont. I mean, it was off the charts how many great musicians were on it. There were no . . . my memory is, you’ve talked to Don, so maybe he’ll correct me. My memory is there were no charts or anything, but that it was all head arrangements, classic style. But that basically, my gig was, I was the guy who had to take his acoustic guitar and go into Willie’s vocal booth when the guests would come in, and kind of work out the tune on my acoustic while they practiced the song.

And my memory is, it wasn’t like these were “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain,” like three chords. It was like, “Okay, we’re going to do an ‘American Tune’ with Paul Simon.” Which is a really complicated tune. And I had to learn it on the spot. I was probably sweating like, “Oh my God, I’ve got to figure out how to play ‘American Tune.’ ” And then Paul, who I admired greatly, and Willie in the booth, and I’m like, “Oh my God, this seems like a big job for me.” But man, it all worked out. I remember on the floor, thinking . . . My approach at that point, was I was kind of organized in the studio, and I had pretty good ideas about who should play what and how, and this, that, and the other thing, probably too much. And Don was the opposite. It was just really loose, and everybody was just figuring out their own parts. Now, of course, these guys are just, every one of them, brilliant.

John Spong: Yeah, it’s Hall of Fame.

John Leventhal: Yeah. Every one of them, in their own way, is a producer. Every one of them, in their own way. This is truly the mark of great session players, which is: the musicianship doesn’t even come first, in my mind; it’s your musicality that comes first. It’s your sense of what the purpose of your being there is. What is the role you’re playing? How do you make the thing better? Not specifically what you’re playing. And then you try to figure out something to help make it happen.

Now, these guys are all top-of-the-heap versions of that. So anyway, when I heard the record, it was amazing. I thought, “God, what a great job Don did.” He really pulled it together. It’s so unexpected and unusual. And yeah, I’ve noticed a lot of people really love that record, man. They really do. They really do.

John Spong: When you talk about setting up the guests coming in, you played on the Sinead O’Connor duet and the Bob Dylan duet.

John Leventhal: Yeah, I remember that one.

John Spong: I mean, any memories of either of those?

John Leventhal: Well, the one I remember most is Sinead, because it was that Peter Gabriel tune, right? “Don’t Give Up?”

John Spong: Yeah.

John Leventhal: Right.

John Spong: The night before, she had gotten booed at the Madison Square Garden.

John Leventhal: Yeah, so I do remember that. Well, I remember it was like . . . I probably was, my head was up a little of my own self, because trying to figure out how to distill the essence of another really deep and complicated song, “Don’t Give Up,” by Peter Gabriel, on my acoustic guitar, so that they could learn it. My main memory of it all is I was kind of wowed by everyone and everything, and I was just trying not to eff it up. I was in some high cotton there, and it’s like I wasn’t going to be the guy to eff it up.

[Willie Nelson singing “American Tune”]

John Leventhal: You’re never going to go wrong listening to Paul Simon. The guy is . . . I mean, in my mind, you could really count, almost on one hand, of artists in pop-music world from that generation, who’ve carried on, thrusting forward artistically, and have not rested on their laurels or tried to rehash the things that worked in the past. Dylan, Paul Simon, I mean, they keep trying to push their own personal envelope. And man, that ain’t easy. That ain’t easy to sustain that for five, in their case, over six decades. That is not easy. You can’t think of visual artists who’ve done it. You can’t think of great novelists who’ve done it. I mean, filmmakers, you name it. So to me, it’s quite impressive.

John Spong: Willie just released his first bluegrass album at the age of ninety.

John Leventhal: See, you got to love that. You just got to love that.

John Spong: Yeah.

John Leventhal: It’s amazing. Yeah. Now I have to go hear that. As soon as we hang up, I’m going to go check that out.

John Spong: It’s pretty good. Well, then to kind of wind down, I’m assuming you’ve gotten to know Willie, somewhat?

John Leventhal: Not really. No, it was just ships passing in the night. I don’t think . . . I think maybe, since that session, which is thirty years ago, maybe I saw him once. I didn’t get the feeling he remembered me. I could be wrong. But he was coming from the tour bus to get on stage, and then maybe after, because I noticed that as soon as the band is still vamping on the last song of the set, Willie’s heading out to the tour bus. So it wasn’t like a stationary meeting, he was in motion.

John Spong: Quick fist bump. Well, I think, because your wife, because Rosanne talked about him with such affection, and in particular, about the relationship between Willie and her dad . . .

John Leventhal: Well, yeah. Yeah, for sure. Yeah. I mean, those guys, come on.

John Spong: Yeah.

John Leventhal: Man, it’s incredible. Yeah.

John Spong: So I think about it, they’re giants. That’s not an overstatement.

John Leventhal: No.

John Spong: And it’s weird though, because when I was thinking, and probably overthinking. But with a lot of great big-deal artists, like say George Strait. A lot of imitators come in the wake of George Strait. And there’s this whole cookie-cutter, hat-country development, which is not a knock on Strait. That’s how good Strait is. But with Cash . . . with John Cash and Willie, there’s no way to do what they do. There’s no imitation. And so I guess, in the interest of overthinking, how does country music, or Americana or whatever, how does music reflect their achievements, if that makes sense at all?

John Leventhal: I don’t . . . now we’re going to get into language. I mean, I don’t know about the word “reflect.” I mean, obviously, it’s informing big swaths of how people proceed in this thing that we’re now calling “Americana,” whatever the heck that is. I mean, even the Americana people don’t truly know what it is. I mean, that’s fine. I mean, that’s fine. Why do we need categories? Because Willie, ultimately, is not categorizable, right?

John Spong: Right.

John Leventhal: I mean, he’s coming from a specific. . . . He starts in a tradition, and you can sense that the tradition he’s coming from, which is the music I’m sure he heard growing up in Texas, and it has to do with what we used to call country music. Then we started calling it roots music or Americana music. It informs everything he does, but that’s not the totality of what he is.

The Americana thing is, I don’t know what to say. I mean, this will circle back, I suppose, if I gave it some thought, and I could be mildly articulate . . . this idea of what is timelessness? What are we really trying to do as an artist or a recording artist, let’s say, because that’s what I do. What are we really trying to do? Now, are we trying to create a product? Well, yeah, up to a point. And some people get mired in that. Some people are really good at creating a product. And some people, like me, maybe that isn’t my strong suit. So what are we trying to do? I mean, I don’t want to get too highfalutin about it, but we’re trying to create this sense of timelessness. We’re trying to make these statements that are valid for all time. When I hear myself say that, it sounds slightly obnoxious, but it is actually what I think it is.

So when you talk about Cash and Willie, and then, I mean also, obviously, I think Waylon was amazing too, and kind of underrated, in some ways. And Kris’s songwriting and just Kris’s stance of . . . the space Kris inhabited as an artist . . . I mean, these guys, why did they have it? Man, when you and I figure that out, we’re going to do really well. But they just had it, right? They had it. You can’t explain the Beatles, either. You can’t really explain, “Why did these four guys from Liverpool . . .” I’ve gone to Liverpool. I wanted to see what the deal was. And you can’t explain it. And John and Paul grow up less than two miles from each other. You can’t explain what it is about the four of them together. You can’t explain what it is about Cash. I mean, I can say something about Willie and Cash in that they had, whether it was totally conscious or creatively unconscious, they had a sense of how to shape and use, in the best possible sense, people’s sense of them, what people projected . . .

Johnny Cash was not what people projected onto him. But he started to sense what was being projected onto him. And he used it in an artful way, in which he created this persona, which I have always said is like, it’s Elvis and Abraham Lincoln thrown into one person, which is the ultimate American archetype. It’s the rebel. It’s the rebel, and the most moral, ethical, soulful father imagined, right? The father we all want, the loving, funny, deep man with the guy who gives the finger to the cameraman, right?

John Spong: Right.

John Leventhal: And Willie in his own way, I think, has his version of that, which is, “I’m going to be free. You’re not going to tie me down. But I believe totally in this tradition. I’m going to be free, but this tradition that I come from, I am embracing in every way.” So they both sort of understood this kind of deep American archetypal thing.

Now, whether they understood it like . . . It’s still not clear to me whether John understood it in a super-conscious way, or whether he was just gifted with ability to do it. I think all four of those guys had it. Now, okay, let’s bring it back to Americana really quickly. Is anybody out there who has that now? It’s hard for me to see it. I don’t personally see it, which is not to say there isn’t great music and great songwriting and great stuff. I tend to feel like most of the stuff that I like, and am moved by, feels overly indebted to stuff that’s happened fifty, sixty, forty years ago, overly indebted. Whereas I always felt like Cash and Willie and the Beatles and Stones sort of took the things that influenced them and created something brand new.

So I don’t really sense that now, but—I can hear my son going, “Okay, boomer.” Yeah, I don’t want to get too old-man cranky, like, “Oh, just the music I like,” because I try to stay open to it. But I don’t know. It’s up for debate, up for discussion. Let your fans weigh in. Here we go.

John Spong: That’s awesome. And especially the way you ended there, because at one point. . . . Your wife was the first person that made me start crying while we were talking on one of these, and then you kind of did for a second there, too. I could not appreciate this more.

John Leventhal: All right, man.

John Spong: It’s really special.

John Leventhal: Well, I look forward to hearing it. And thank you for thinking of me. It’s a left-field kind of thing for me, but I like it. I like it. And it connects an experience I had playing on a Willie record, which I’m certainly thrilled I got to do, and be able to talk about. You know what I mean? I don’t often get to talk about these kind of highfalutin artistic ideas, so thank you.

[Willie Nelson singing “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain”]

John Spong (voice-over): All right, Willie fans. That was John Leventhal talking about “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.” A huge thanks to him for coming on the show, a big thanks to our sponsor, Still Austin craft whiskey, and a big thanks to you for tuning in. If you dig the show, please subscribe, maybe tell a couple friends, and visit our page at Apple Podcasts and give us some stars. And please also check out our One by Willie playlist at Apple Music.

Oh, and be sure to tune in next week to hear Texas country superstar Wade Bowen discuss Willie’s first recorded ode to life on the road:“Me and Paul.” Oh, and let me just add here that Wade zoomed in from his tour bus, which was broke down somewhere outside Omaha. If there’s a more fitting context in which to talk about “Me and Paul,” it hasn’t occurred to me yet.

We’ll see you guys next week.

- More About:

- Music