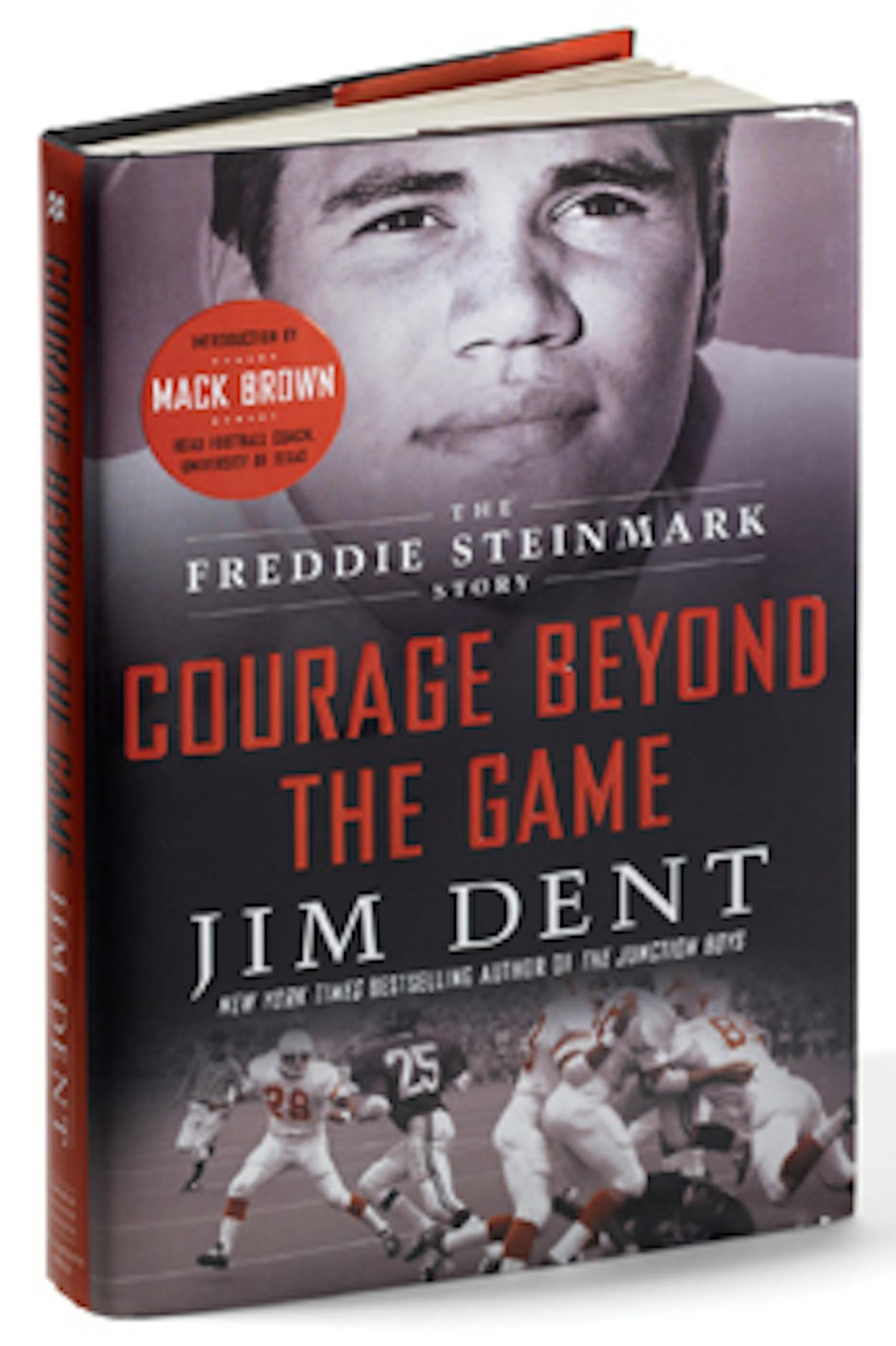

An undersized country kid becomes a big-time college football player. Freddie! Freddie! A Longhorns stud fights cancer after leading his team to a national title. Freddie! Freddie! You can practically hear the whoops bursting out of Jim Dent’s Courage Beyond the Game: The Freddie Steinmark Story (Thomas Dunne Books, $25.99). This book is a pep talk, an end zone dance, and a tribute to the Way Life Oughta Be Lived. Reading it made me feel awful.

Steinmark was a safety on the 1969 University of Texas team who played hard and died young. His tale runs on the same celestial scoreboard as Brian’s Song, Bang the Drum Slowly, and other sports weepies. The problem is that the retelling quickly devolves into a quasi-religious parable. In Courage Beyond the Game Steinmark becomes Saint Freddie, a smiling statue in the player’s lounge. There should be a word for what happens when an athlete falls into the clutches of a swooning sportswriter like Dent. He gets pedestaled.

Freddie Steinmark was born in 1949 in Wheat Ridge, a rural town outside Denver. By third grade, his dad, Big Fred, had put him on a brutal schedule: football six days a week, in two midget leagues. In high school, Freddie became a scooting running back and returner, teaming with future Longhorn Bobby Mitchell as the Mr. Inside and Mr. Outside of Wheat Ridge High. He won a Colorado state title his senior year.

In relating this highlight reel Dent tells us that “Freddie Steinmark was bigger than the Beatles.” In high school. You don’t need to have lived in Wheat Ridge in 1966 to know Dent is leaping a few feet offsides here.

Despite Steinmark’s success, Darrell Royal was the only big-time coach who offered a scholarship to the runty 154-pounder. In 1967 the Longhorns were lurching through a program-wide hangover much like the one the team is experiencing now, and Steinmark helped spark the turnaround. In his sophomore year, Steinmark went from fourth-string safety to first-string. He intercepted five passes. Just the sight of him at his locker, Dent writes, made Royal smile.

Did Steinmark ever make a mistake? In my study of Longhorn football, I’ve learned that every Longhorn has a rotten day, even Vince Young (it was November 25, 2005). In a book that chronicles his high school make-out sessions, Dent never shows Steinmark dropping an interception or blowing an assignment in his prime—though we do learn that “vitality seemed to flow through his pores.”

Steinmark’s junior year at Texas was the best and worst year of his life. The Longhorns had a supporting cast that could have won CMA Awards with their names alone: Woo Woo Worster, Cotton Speyrer, Happy Feller. Texas won its first nine games and headed into a matchup with unbeaten Arkansas that was dubbed “the game of the century.” But Steinmark was feeling bad. His left leg hurt. He could barely walk to class. He played valiantly into the fourth quarter against Arkansas, when Royal finally pulled him out of the game.

It turns out Steinmark had osteosarcoma, a vicious cancer that was gnawing away at his left thigh. “In essence, the final inch or so of Steinmark’s leg possessed no bone,” Dent writes. Six days after the game, doctors at M.D. Anderson amputated the leg. Steinmark came out of the hospital sprinting. “Freddie got more girls with one leg than the rest of us did with two,” one teammate marvels. Richard Nixon, forever in search of his lost football career, brought Steinmark to the Oval Office. Steinmark lived the high life back in Austin off of money that poured into the Freddie Steinmark Fund. (Here, at least, Dent shows Steinmark drinking and carousing and grappling with real emotion.) Then the cancer reappeared, and he died in 1971.

It’s moving stuff. Coming after a year that Longhorns fans spent bitching about the offensive coordinator, Steinmark’s story could be a gentle reminder that all of us are mortal. But here comes Dent again. “No player was ever more loved by his coaches and teammates.” No player—ever? “Freddie Steinmark was the most courageous person ever to play sports.” More courageous than Lou Gehrig, who legged out singles while his nervous system was disintegrating? “No one lived their life any better than Freddie Steinmark.” No one? Would Steinmark—a devout Catholic, we’re told again and again—agree that he was on the same plane as Jesus, Moses, and Cal Ripken Jr.?

Dent dresses poor Steinmark in a jersey ten times his size. You barely get a feel for the real guy. Here’s my read: Steinmark was obedience squared. Big Fred worked him so fiercely that when he came to Austin there wasn’t a sadistic football drill Steinmark would bat an eye at. And Coach Royal, like his brethren across college football, could be a real sadist. Embarrassed by his own lethargy and his team’s downward spiral after the ’63 national title, Royal staged a brutal Junction Boys–style camp in the spring of 1968. According to Dent, many Longhorns quit the team or collapsed on the way back to the dorm.

In football in those days, a “good kid” was one who always said yessir. When Steinmark’s leg started aching, he didn’t complain, because he knew Royal admired injured boys who played through the pain. That’s the Freddie Steinmark story, a two-character tragedy. The kid who molds his life to the medieval rules of college football winds up playing for the coach who helped write them. Both men so detest being hurt—it’s like an act of disobedience!—that it leads to a mutual blindness while cancer festers in the kid’s leg. A book that poked at that sensitive spot, and was willing to come away with an unhappy conclusion, would be a book worth reading.

Dent, a longtime Dallas sportswriter and the author of a book about the Junction Boys, quotes a doctor saying that even early detection of the osteosarcoma might not have prevented the amputation. But he’s raising one hypothetical without considering the other: that early detection might have helped. The omission is characteristic of what Courage Beyond the Game largely lacks: the dropped interceptions, the tricky little bounces of the football, and, most of all, the hard thinking. The longest yard turns out to be the one between Dent’s keyboard and his brain.

A foreword by Longhorns coach Mack Brown is revealing too. Brown has told his players the story of Freddie Steinmark, and before home games they touch Steinmark’s picture in reverence. Brown carries another picture with him on the road. In his canonization of Saint Freddie, then, the sportswriter is following the lead of the football coach. Freddie got pedestaled twice! I can be equally shameless when I say we owe it to the guy to bring him and his good leg down to earth again. We owe it to him because he was a good ballplayer and because he had a bad break and because his final days left a lot of people with a touch of inspiration. Those are real compliments, because they’re paid not to a god but to a man. Yell it out with me: Freddie! Freddie! Freddie!

Textra credit: What else we’re reading this month

David and Lee Roy, David L. Nelson and Randolph B. Schiffer (Texas Tech University Press, $29.95). A Marine remembers a friend who was killed in Vietnam.

An Unquenchable Thirst, Mary Johnson (Speigel & Grau, $27). A young woman leaves her family in Beaumont to become a nun and work alongside Mother Teresa.

Texas High School Football, Joe Nick Patoski (Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum, $29.95/$19.95). The catalog to the current museum exhibit.