God, as is His custom, has once again confounded the wise. After listening to a generation of theologians speak bravely of His death, the Almighty has established Himself as the odds-on choice for Comeback of the Decade. Conservative churches are growing, evangelical Christianity has been declared mainstream American religion, and a Southern Baptist Sunday school teacher has become Leader of the Free World. And now, as if that were not enough, the Baptist General Convention of Texas is about to launch a media blitz designed to share the good news of God’s love with every man, woman, and child in the state an average of forty times apiece during a four-week period in February and March. The $1.5 million campaign, to be called Good News Texas, will feature commercials for Christ on television and radio, ads in newspapers and other print media, booster spots on billboards, pins on lapels, and an extensive personal visitation program to be run by the local churches. It is going to be pure Baptist. Well, almost pure. To help them do it right, the Baptists have hired one of the largest and most successful advertising firms in the country, the Bloom Advertising Agency of Dallas. Neither Sam nor Bob Bloom has roots in the Christian branch of the Judeo-Christian tradition.

I have mixed feelings about all this. Some of my best friends are Baptists, always have been. Still, I have never been able to shake completely the conviction that Baptists are the Aggies of religion. That in itself is not enough to damn them, but it does sort of set them apart. Part of my problem with Baptists stems from the fact that I grew up in the Church of Christ (Romans 16:16). As you may know, Church of Christ people believe the circle of the saved is rather small and not many of them would care to sound too certain about their place in it. Baptists, on the other hand, never seem to tire of telling how sure they are they are saved and how good this blessed assurance feels. I thought their “once saved, always saved” doctrine of salvation was unsound—too easy; cheap grace; why, that would mean you could do anything you wanted to—but at least they had some doctrine, which was more than you could say for the Methodists, and at least we all agreed that nothing could send you to Hell faster than kissing the Pope’s toe. No, the main problem wasn’t doctrine. It was style. No matter what I believed, I could no more have been a Baptist when I was growing up than I could spend every Thursday night at the bowling alley or wear a seafoam-green leisure suit today.

For one thing, Baptists were so organized about inviting people to church. Once I was in the barbershop getting my weekly haircut when Mr. Joy Tilley, who was a big Baptist—I think it says something that the counterpart of “staunch Presbyterian,” “devout Catholic,” and “pillar in the Methodist Church” is “big Baptist”—stuck his head in and invited the barber to come sit in his pew at a revival then in progress. That astonished me. We had a few elderly members who sort of had squatter’s rights to pews they had occupied for years, but we would never have dreamed of assigning somebody a particular pew and then sending them out to drum up people to pack it.

The contrast carried over to the revivals themselves. The mark of a successful Church of Christ revivalist was his ability to drive the nail of terror into slumbering souls. Though some Baptist revivalists made use of hellfire and brimstone, I always felt that the mark of a successful Baptist preacher was his ability to make you laugh and feel good. That didn’t seem much like religion to me.

This difference was further reflected in the Sunday schools, where we gave our classes sensible, functional names— “Preschool,” “Elementary,” “Junior High,” and “Young People”—and encouraged attendance by quoting scriptures, especially Hebrews 10:25 (“For-sake not the assembling of yourselves together”), and threatening slackers with hellfire. Baptists called their classes things like “Sunbeams” and “Pioneers” and “Aviators” and drew crowds by having the youth minister bounce over the church bus from a trampoline.

I used to marvel at what they would do to appeal to young people. Our high school assembly programs fell into two primary categories: magicians, myna birds, and trick-shot artists sent out from the Southern School Assemblies organization and—this was before Ms. O’Hair took God out of the schools—preachers holding revivals over at the Baptist church. They would juggle and tell a few jokes and then talk to us earnestly about taking care of our bodies, which are temples of the Holy Spirit (I Corinthians 6:19). Once a revival team from Baylor entertained us with several hymns and gospel tunes arranged for trumpet trio. Then the leader, a young man with the unforgettable name of Horace Oliver Bilderback, placed a trombone mouthpiece in his trumpet and played “Let the Lower Lights Be Burning” while one of his fellow clerics moved an imaginary trombone slide out in front. That, to me, was the pure essence of the Southern Baptist Church.

At times, to be sure, I envied my Baptist friends and made some effort to be one of them. I went to the Baptist Vacation Bible School several years and made bookends and potholders and whatnot shelves, and did right well at a Bible game called Sword Drill—“Attention! Draw swords! (No thumbs over the edges, now.) John 3:16! Charge!”—and I thought it was keen that their pastor, Brother Rose, illustrated his devotional lessons with magic tricks and showed us slides of his trip to the Holy Land. Once, I joined the Royal Ambassadors (and got elected Ambassador-in-Chief) just to have a chance to go to the summer encampment at Alta Frio, but I lost my nerve before the bus left and stayed home. Later, I longed to go on hayrides and swimming parties with the Training Union and even wished I could go into San Antonio and hear Angel Martinez preach in a white suit. But it was just no use. I was like a lonely traveler watching a group of Shriners cutting up in a hotel lobby: it might be fun for a day or two to wear a fez and ride a little motor scooter down Main Street, but you wouldn’t want to go home and still have to be one.

Before all the Baptists walk out on me, I have a confession to make. About four or five years ago, I became sort of a Baptist myself. After spending the better part of the sixties studying religion at Harvard, I grew a bit weak on matters of doctrine and decided I would do more harm than good by sticking with the Church of Christ. When I came back to Texas, I cast around a bit and finally wound up at a church which I suppose could be described as liberal and ecumenical, though even now I find it difficult to identify myself as a theological liberal, so strongly was I taught to believe that few states of being are more pernicious. Still, at least half the people in this church grew up as Baptists, a good handful of them are former Baptist preachers, and even though the Union Baptist Association of Houston threw them out for accepting members from other denominations without rebaptizing them, they still persist in calling themselves Baptists. I have had some trouble with it. I am embarrassed when they look at me in amazement because I have never heard of Lottie Moon, and I get a little squirmy when they sing “Do Lord” at the annual retreat up in the woods, and I admit it doesn’t make a dime’s worth of difference to me whether Baylor wins or loses a football game. Still, we don’t have revivals and if we did we wouldn’t have trumpets or trombones or jugglers, and nobody checks to see why you haven’t been coming to Sunday school and, as far as I can tell, nobody much cares about the details of your belief, so long as you are kind and try to help folk when they need it. It doesn’t have anything like the zip of a straight-out evangelical church, but ex-Fundamentalists are some of the best people you’ll find anywhere, so I expect I’ll keep my letter in a while longer. Besides, if Good News Texas works, we may all be Baptists by summer.

Baptists, of course, have always been aggressive. They sought “A Million More in Fifty-Four” and they have sponsored Billy Graham Crusades and hold “Win Clinics” to instruct people in the techniques of personal evangelism. But this is bigger, better, grander than anything they have ever done before.

My immersion in the project came in Dallas at a regional meeting of the Baptist General Convention of Texas (BGCT). The Good News Texas portion of the program was co-chaired by Drs. L. L. Morriss and Lloyd Elder. Morriss, with his smooth gray hair, metal glasses, and high-quality fall woolens, could easily pass for a corporation executive. His speech and manner befit his appearance—one senses he does little by accident. Lloyd Elder’s obvious intelligence, warmth, and gentle wit are engaging, but his slightly more rumpled look and apparent unconcern for slickness make it easier to believe he is a seminary professor or church executive.

Morriss declared he was as excited as “an auctioneer at an auction of used furniture,” a metaphor I thought fell somewhat short of the mark. He was excited, he said, about what God had done for Texas in the past and about what He is doing now. He introduced Elder, who was also excited. Good News Texas, Elder said, would have three major targets: (1) the 4.7 million Texans—one third of the state’s population—who do not belong to any Christian group, persons “who are completely uninvolved in the things of Christ,” (2) inactive and apathetic church members, including 700,000 Baptists, and (3) the active membership of local Baptist churches. He summarized what the Bloom Agency had done so far and sketched out the main lines the media campaign would follow. Then he reminded the assembly that Good News Texas “is not a goodwill campaign for the convention. It is not church advertising. It is going with the best product we have, and that is the gospel of Jesus Christ.” Elder then called on Dr. Jimmy Allen, the pastor of San Antonio’s First Baptist Church. Alien is a big man who wears his graying hair rather long for a Baptist preacher and gives off an unmistakable impression of high energy. Working from a few notes scribbled on the back of an envelope, he spoke of “the rhythm in the way God moves in His world, in the tide, in our heartbeat, in the very energy levels of our lives.” “There are times,” he said, “when God moves in great force and power in our lives, and then there are times of wandering in the wilderness when we begin to appreciate the fact that we cannot live in ecstasy all the time. There must be a hunger before there is filling. There must be thirst before there can be a slaking of thirst. I am convinced we are at the edge of a spiritual awakening in our nation and that some of us are in places where we can already sense the tide of God coming in.”

Allen noted that Newsweek had carried Charles Colson’s testimonial, that the Fort Worth Star-Telegram had printed an editorial that told how to be saved, and that CBS had interviewed members of his church for an hour-long documentary on the meaning of salvation. He went on for about twenty minutes, talking about how much we needed revival and how much he hoped God might choose Baptists to be part of the central apparatus by which He moved. Then, in a hushed voice that visibly moved the audience with its intensity, he concluded: “I find myself saying, ‘God, could this be the time? Lord, could you be ready now? Is it something that will take our breath away?’ I find myself saying, ‘O Lord, let it be good news, not just for Texas, not just for Texas Baptists, but for a nation and a world that desperately needs to find out that, indeed, there is good news.’ ”

Later that afternoon, I sat down with Morriss, Elder, and BGCT executive director Dr. James Landes. Though he was quick to note he is a chemical engineer by training, Dr. Landes’ beneficent countenance and rather sermonic manner make it clear he has been around a lot of preachers.

“The rationale of Good News Texas,” Landes said, “is the commandment ‘Go ye into all the world.’ I have seen the heartbreaking conditions so many people are experiencing throughout this state. I had no alternative but to study how to spread the message that there are people in the world who care, who are interested in persons just because they are human beings, regardless of race or color or creed, and that the reason these people care is because they believe God is, and Christ is, and the Scriptures are a mirror of Christ’s mind. I realized also that many of our leaders were reaching out for some undergirding arm that could strengthen and help them in their ministry in the local church. So, as I thought and prayed and did a bit of meditating in between fly fishing on the riverbanks of Colorado, I said, ‘Lord, if this great big denomination with two million people and forty-two hundred churches and missions will make up its mind to do one thing across a period of a couple of years, there is no telling what good could come of that.’ And I thought if we could just plant a seed, maybe it could grow, maybe it could bless a whole state and the nation. I shared that dream with my associates here on the administrative staff and they asked me to share it with the executive board. I came away somewhat shocked but deeply gratified, because men who do not normally react enthusiastically to another evangelistic thrust got to their feet and said, ‘This sounds different, get with it!’ ”

As we talked, Landes and his colleagues echoed what Jimmy Allen had said about the soon-coming revival. Exciting things are happening among our laymen, they said. Signs of awakening are blowing across our nation. But if revival was coming with or without their help, as they seemed to be saying, why didn’t Baptists take their $1.5 million and spend it some other way? “Somebody has to be the agent,” Landes replied. “God always works through an Abraham, a Moses, an Isaac, a Joseph, a John the Baptist. He doesn’t work without working through people. If Texas Baptists have the favorable image the research for this project shows we have, then we’ve got a responsibility commensurate with it. If God wants to use us, we have a responsibility to be available.”

I brought up something that had struck me from the moment I saw the first piece of promotional literature about Good News Texas. The logo for the campaign is the Christian fish symbol, with the state of Texas stuffed inside it like Jonah. To accommodate both Amarillo and Laredo, the fish is drawn a bit fat, so that it looks something like a football with a tail or perhaps a Gospel Blimp. Several years ago a mild satire, widely circulated in evangelical circles, described the misadventures of a Christian group that hired a blimp to broadcast sermons and drop leaflets on the hapless community below. Though it attracted great attention, the townspeople were irritated and offended, and the initial spirit and purpose of the enterprise were lost and perverted. I was curious about whether these men had considered the possibility that Good News Texas might be a Baptist version of the Gospel Blimp.

Elder was aware of the perils. “If we just saturated the media with the gospel message,” he said, “and expected something to happen automatically, that would be the Gospel Blimp approach. Just pay your money and send up the blimp. But we are making a real effort to keep that from happening. We are trying to equip ministers and lay people in the local churches to be witnesses, so that they don’t just let the blimp fly over, but can knock on doors and present the gospel to people as caring, sharing neighbors.”

Jimmy Allen had said Baptists would need to remember that “when God comes to town, He doesn’t always stay in our house. He moves where He chooses to move and leaps over all kinds of barriers.” How would they feel if the Methodists or Presbyterians or Church of Christ picked up some new members on Baptist nickels? The prospect did not seem to dismay them. They were, in fact, informing other denominations in the state about their plans so that if the awakening comes, they can also be ready for it. There is, of course, some confidence that their 4200 outlets will give Baptists a healthy share of whatever market develops.

This ecumenical talk emboldened me to raise a point I regarded as of at least mild interest. Why had they chosen the Bloom Agency? Granted, it was recognized as one of the best agencies in the country and its Dallas location provided the advantage of close and frequent contact, but was there no sense of incongruity in hiring a Jewish-owned agency to conceive and produce an evangelistic campaign for Southern Baptists? Apparently not. The Baptists chose their agency the same way Procter and Gamble or Exxon might, with a steering committee of seventeen people and a much larger consultation group from across the state which heard presentations by a number of respected firms.

“Bob Bloom is a good salesman,” said James Landes. “When he was through, I heard a Baptist preacher from East Texas say, ‘I don’t need to hear anybody else. The man knows where he is going.’ When that group voted, they did so with a great feeling of confidence in the ability and desire of the Bloom Agency to help us do what we wanted to do. It was almost unanimous. It was an overwhelming decision.” Landes admitted to some early personal reservations but insisted things had worked out “more beautifully and fantastically than we had expected.” Then he suggested I check out the backgrounds of the men at the agency with primary responsibility for the account.

The Bloom Agency occupies several floors of the Zale Building, which sits alongside Stemmons Freeway like a giant homemaker’s misplaced toaster. Instead of the customary rooms and hallways, the agency uses “action offices,” work spaces defined by movable partitions about five and a half feet high which can be shaped to fit needs that change with each new client or campaign. Flexible white hoses bring electrical and telephonic nourishment to each of the modules, so that one can tote up the number of offices currently in use by counting the accordion-pleated umbilici. The occupants of these spaces decorate them as if they are planning to stay for years, so I presume one has a fair chance of hanging onto one’s own partitions, but I was told reshuffling is not uncommon.

The furnishings run heavily to chrome, glass, and plastic, with plenty of plants and bright colors. Most of the offices are densely decorated in pop-artifactual chic, with tapestries and macramé hangings and inspirational posters framed in Lucite and fire-alarm boxes and street signs and—everywhere—reminders and remnants of past campaigns. Shelves in the reception area hold symbols of the agency’s various clients: Bekins, Southwest Airlines, Owens Sausage, Amalie Motor Oil, Rainbo Bread, Lubriderm Cream, Whataburger, and a score of others. I looked in vain for a New Testament or a Broadman Hymnal, but I guess the display had not yet been brought that far up to date.

Bob Bloom showed me around and talked about the Baptist account. “We are in the consumer advertising business,” he explained. “Our job is to communicate with the general public and get a response from them. That is what we do best. We try to generate retail purchases, to get people to buy motor oil, or a home, or seats on an airplane. We have never been involved in anything like this before, but the thing that stimulated us was the feeling that the BGCT could give us what we want in a partnership role, a sharing of responsibilities as opposed simply to doing what we tell them. They know how to listen, how to guide, how to tell us when we are off base, and they know how to stroke, so we are pleased to have the association from that standpoint. I was impressed that they could not only accept but embrace aspects of our craft that we have difficulty getting business people, including some Harvard MBAs, to accept.”

How did he account for this? “I’m not really sure,” Bloom said. “I guess they are just smart. I had expected a sharp drop-off in intelligence between the leaders of the organization and the men in lower positions. In a business organization like a bank, for example, once you get past the president and a few directors to some of the department heads, you find some terrible prejudices about certain things, a lack of understanding about advertising and research, and an unwillingness to bend. I expected that with the Baptists, but frankly, I found a lot of sharp men at all levels. And they are very flexible. When we got out with the pastors, I expected to confront some prejudice, both from my being Jewish and in their willingness to marry our craft with their pulpit responsibilities. I just didn’t find any of that. I found a high degree of comprehension when we went through the various alternatives with them. I kind of expected someone to get up and make an appeal to ‘throw all that stuff away and just give people the simple gospel.’ It didn’t happen. They had smart, agile minds and they really embraced what we were trying to do. If I could get forty rabbis together to do that, I would be terribly surprised. They are also very sincere about the undertaking. It is great to have a client who believes in what he is doing, as opposed to someone who is just grinding out a product.”

Did he have any misgivings about mounting a campaign whose basic premise he, as a Jew, did not believe? “I never felt any real sensitivity on that issue, except in regard to the terminology, which was very alien to me. Once I became confident they were willing to accept me as a spokesman for the agency and as a craftsman with some expertise, I became very comfortable with it. My role has been much the same as with any client. I feel I am particularly good at organizational work and strategic thinking. I am not concerned with the technological aspects of a motor oil—what it will or won’t do for an engine—and I can’t comment on the religious aspects of this project. What I am interested in is how we can communicate the selling points to the customer.”

Bob introduced me to his father, Sam Bloom, the agency’s founder, who professed an interest in the project that went beyond craftsmanship. He was concerned “about both the standards and ethics which appear to be declining in politics and business.” The Baptists, he thought, were on the right track on these matters. Their willingness to lay $1.5 million on the line to bolster the ethics and morality of the state was a courageous act and he was “terribly enthused” to have a part in it.

I visited with most of the key personnel working on the account in the agency’s new think tank, a tiered and carpeted room with no furniture except for ashtrays and huge pillows covered in plaid, madras, batik, and Marimekko. A tray on one of the lower tiers held coffee, Styrofoam cups, little packets of Cremora, Imperial Sugar, Sweet ’n Low, and a box of those red-and-white plastic sticks that are too skinny to stir anything. On the assumption, I presume, that ideas generated in the room would be too dramatic to jot down on 3×5 cards with a ball-point pen, jumbo pads of paper and Magic Markers lay within easy reach. While a person in Faded Glory jeans with stars on the pockets went out to get Frescas and Tabs and Cokes for the non-coffee drinkers, we took our positions, shifted around a bit to look properly relaxed, and began to talk.

Dick Yob, research director for the project, explained that “the days of doing what we think will work are becoming extinct because of the amount of money that is involved. We have to go out and find what really does communicate. Our approach has been to come at this like we would any package goods account, since that is basically what we know how to do.” The first step had been to see what problems were bothering Texans these days. To accomplish this, Yob hired the Dallas marketing research firm of Louis, Bowles and Grove, Inc., to show a list of problems to approximately 300 Dallas and Austin citizens—divided evenly between active Baptists, inactive Christians, and non-Christians—and ask which most accurately mirrored their own feelings and which were the problems they heard other people discuss. On both counts, all three groups ranked hypocrisy as the number one problem, by agreeing with such statements as “It’s getting harder to trust anybody or anything” and “People are not what they pretend to be. They say one thing and do another.”

Survey participants were then offered three possible solutions: (1) reading the Bible, (2) joining a group of active Christians, and (3) entering into a personal relationship with Jesus Christ and following his teachings. All three groups agreed that of the three answers, Christ was the best—though only 27 per cent of the inactive Christians and 14 per cent of the non-Christians actually felt it was an appropriate solution for them. More than two-thirds of the non-Christians chose none of the three options. In short, despite evidence of considerable spiritual and emotional malaise among backslidden and secular Texans, the field appeared to be something less than white unto harvest. Still, the Baptists and the agency agreed that a personal relation with Jesus was the most commercial of the products they had to offer. The next step was to decide how to package it for wholesale distribution.

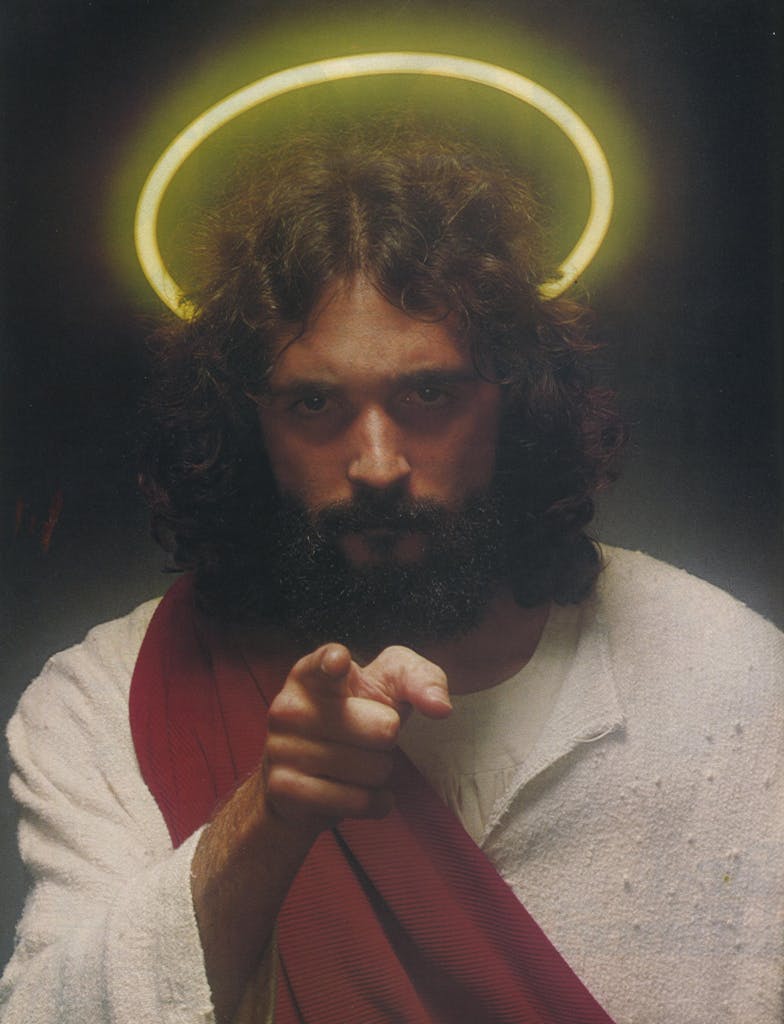

At this point, the burden shifted to Bill Hill, the agency’s creative director. He did not find the yoke an easy one. What could they say that would communicate effectively to all three target groups? And what vehicle would they use to say it: testimonials? dramatizations? slice-of-life vignettes? cartoons? jingles? During our first conversation, Hill had a discernible case of advertiser’s anxiety. “We are trying to avoid coming across as too churchy,” he said, “and we want to avoid clichés. The men working with us from BGCT are theologians. When they say ‘Christ died for you,’ there is a lifetime of knowledge behind it and all sorts of subtleties ripple out of it, but to the people they have singled out as the primary audience—non-Christians—that is a cliche and it may be a turnoff. We want to save the Jesus message to the very end of the TV spots, so we can get people nodding and saying, ‘Yes, that is a problem. Yes, I would like to have a solution to that problem.’ Then, at the end, we want to say, ‘That solution is available to you through Jesus Christ.’ We are trying to say, in the simplest form possible, that ‘something that happened two thousand years ago is a real force that is relevant to your own individual problems right here and right now. If you are really concerned about your own problems and about what is going on in the world, and you have tried everything else, what have you got to lose?’ We are not really trying to say how Christ is the answer, but simply that He is. We may go into how a little more in the other media.” The problem of doing justice to the gospel in a brief commercial is tough, Hill admitted: “I keep writing forty-two-second commercials because I just can’t boil it all down into thirty seconds. In a thirty-second spot, about all we can say is, ‘This aspirin contains more pain relievers than all the others combined.’ ” Guy Marble outlined the key public relations aspects of the campaign. His main task would be to bombard local churches throughout the state with newsletters, articles, speeches, posters, lapel buttons, and other communiqués to allow them to take full advantage of the media campaign when it hit their area. The agency people and Baptists both agreed that the word would be barren, like seed on stony ground, unless the local churches were ready not only to urge personal evangelism, but also to accept and nurture those who might be converted. As Jim Goodnight, who has overall responsibility for the account, put it, “We are going to give people the opportunity to respond, but when a guy walks in the back door of a Baptist church some Sunday morning to find what he has been looking for—what happens then will be up to the members of that church. If they are not ready for people who may not share any of their values, then it won’t work. If they are ready to accept people ‘just as I am,’ I believe there will be a tremendous awakening of visible growth in both numbers and spirit.” Another promotion task will be to make sure the local churches understand the strategy that will govern the campaign. “When we buy time for these commercials,” Goodnight explained, “we are not going to be buying the Sunday Morning Revival Hour. We are going to be buying Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman and All in the Family and Sonny and Cher. You can anticipate the kinds of reactions thousands and thousands of Texas Baptists are going to have—‘What are we doing supporting that kind of program?’ Of course, our purpose is not to support the program. It’s where we have to go to reach the people we want to reach.”

Despite the frequent comparison of selling the gospel to selling aspirin or motor oil, it seemed clear these men were taking the matter more seriously than that. I recalled what Dr. Landes had said about checking their backgrounds, so I asked each of them to characterize his religious position. The agency didn’t exactly turn out to be a collection of Madison Avenue cynics. Dick Yob is a graduate of Catholic University at Marquette, sends his oldest son to parochial school, and is active in the Church. Bill Hill is the son of a Baptist preacher in Amarillo but became so disillusioned with evangelical Christianity by the time he reached high school that for several years he dabbled in Zen, studied Rosicrucian literature, and considered going to live with the Dalai Lama in Tibet. Instead, he got married and became an Episcopalian. For the past seven years, he has participated in a Bible class taught by conservative Biblicist Mai Couch, a graduate of fundamentalist Dallas Theological Seminary who specializes in the interpretation of Biblical prophecy. Public relations advisor Guy Marble describes himself as “a lapsed Methodist,” but his colleague Frank Demarest is a member of the Northwest Bible Church in Dallas (also aligned with the Dallas Theological Seminary) and admits he stands a bit to the right of Southern Baptists in his theology. Jim Goodnight grew up in the Park Cities Baptist Church in Dallas but switched to the Church of Christ after he married the granddaughter of G. H. P. Showalter, a Church of Christ patriarch and former editor of one of its most conservative papers, the Firm Foundation. Though he locates himself in “the liberal, ecumenical wing of the Church of Christ” (a figure of speech like “virile impotence”), he is still active in the Preston Crest congregation in Dallas and has taught classes in C. S. Lewis’ Mere Christianity, hardly a radical treatise.

These men, it turns out, are not the only Christians in the Bloom Agency. “You would be amazed,” Goodnight said, “at the number of people within the agency who wanted to work on this account. Not only have a number of these closet Christians surfaced, but about twenty-five of them now meet each Wednesday at noon to pray and share our concerns and testimonials.” “It’s really neat,” Demarest said. “All our working lives we have had this separation between our Christian faith and what we do on our jobs. For me, this is the first time to bring the two together.”

“There is a terrible intensity among the people on the team,” Hill said. “This is not just another piece of package goods. This is something that is going to affect people’s lives. I really feel what I am doing. I keep thinking, ‘We are going to save Texas!’ and that gets to be a bit of a hang-up and causes a mental block.” Another problem Goodnight observed is that “each of us gets his own theology and beliefs, his own personal slant woven into it. One of the hardest things to do in any advertising is to wash yourself out of it and consider only the people you are trying to write for and what their needs are.”

“With most products,” Yob pointed out, “you are selling to people who are already users. It is a matter of getting them to switch brands or buy more of your product. But in this campaign, non-users are the number one target.”

That afternoon I attended a meeting between members of the Bloom team and key staff members at the Baptist Building. Mainly, they were catching each other up on how things were going in their sections of the ball park. Jim Goodnight read the strategy statement that had emerged from their research. “What we are trying to do,” he said, “is communicate to people that the frustrations they experience with the hypocrisy and lack of integrity in today’s world is the result of misplaced priorities, and that the solution is to place their trust in Jesus Christ who will never fail them, rather than on the imperfect things of the world.” The Baptists liked that a lot.

Demarest, Marble, and Mary Colias Carter reviewed PR plans. A steady stream of articles would appear in the Baptist Standard to “soften up the terrain,” and a piece would appear in the next issue of the Helper, BGCT’s women’s magazine. Pastors would be supplied with information they could use to raise money for the program. Every church would receive material explaining the nature and scope of the project. Marble reported that he and his associates had done “much agonizing posterwise,” but promised the first in a series of posters would be ready in “six weeks max.”

They also talked a bit about honorary chairmen. Billy Graham had agreed to serve as national honorary chairman, but both the Baptists and the Bloom representatives wanted to make sure the campaign did not become a Graham affair. “We are not going to be able to use him much in a public way,” Marble said. “If he is flying from coast to coast, we may be able to get him to stop off at DFW airport for a press conference and say how great Good News Texas is. We can do little things like that without much financial or time commitment, but that will be about the extent of it. Right now, we just want to get half a day with him at his place in North Carolina to produce several short items that could be used to stir up enthusiasm in the local churches.” In addition to Graham, two state chairmen would be chosen—people who could generate prestige and interest in Jesus just by their association with the campaign. After all, one Baptist executive observed, “Public relations is the name of the game.”

Over the next several weeks, Bill Hill and his associates developed four protocommercials in “animatic” form—a series of still drawings with voice-overs rather than the live action or true animation that would be used in the final product. Each of the four took a different slant and would be tested to see which, if any, might appeal most to the Texas contingent of a lost and dying world. If none clicked, it would be, quite literally, back to the drawing board. If one seemed clearly better than the others, it would become the model for the actual spots to be used in the campaign. On three successive evenings in early October, representatives of Louis, Bowles and Grove showed the spots to “focus groups” drawn from the three target populations. Active Baptists met the first night in three churches scattered around Dallas.

I am not supposed to identify either the church or the people I observed, so I won’t, but I promise you it was a real Baptist church, with a poster thermometer in the foyer that showed how the fund drive was going.

Judy Briggs, a market researcher for Louis, Bowles and Grove, told the group they were to give their reactions to some commercials being prepared for television. She did not say they were Baptist commercials or mention Good News Texas. She then showed the commercials on a videotape machine and asked the group to fill out a questionnaire after they viewed each one.

The first commercial, identified as “Promises,” offered shots of politicians, automobile dealers, and various businessmen making familiar promises—“You’ve got my word on it.” “It’s a sure thing.” “You can depend on it.” It ended with a note to the effect that Jesus is the only one whose promises can be trusted and “Isn’t it time we listened?” The positive responses to “Promises” indicated the Christians held a disillusioned view of humanity: “Everybody is trying to put something over on us.” “People will let you down, but if you trust in God, He won’t let you down.” “You have to put your faith in the Lord and not in other people.” I got the message, but I felt sad, and the stark ceiling light illumined other, almost forgotten rooms in my soul, rooms not furnished with warm and reassuring memories, rooms abandoned because the heat had been shut off and the broken panes let in too much damp and cold.

The next example showed a man arising to the sound of a strident alarm and struggling to meet the day as he listened to the depressing litany of the morning news. Then a voice-over announcer asked, “Wouldn’t it be a change to wake up one morning without anxiety over what the day might bring? To know that whatever the world throws at you, you’ll make it? If that kind of change would be welcome, then get with the one person who can do the changing—Jesus Christ. For a change.” This, too, seemed to confirm the experience of the group: “We can’t depend on the news being good,” they said, “but if we have Jesus Christ with us, it makes no difference. You have to have Him because what problems can you face without Christ?”

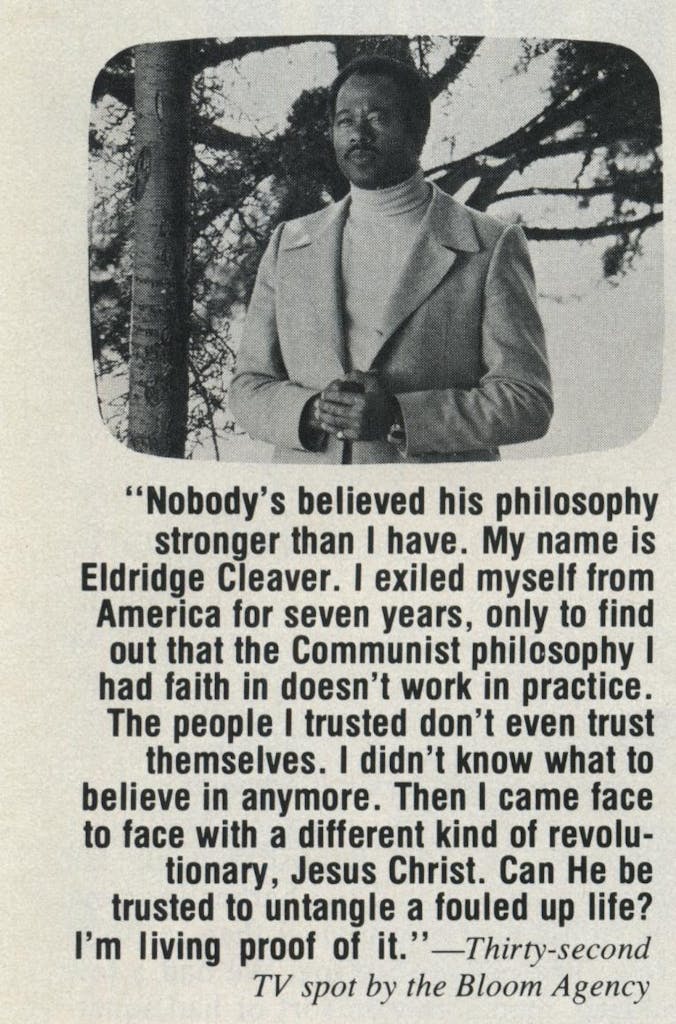

The third effort did not lend itself so easily to clichéd response. In this one, a black man told of how he had been a revolutionary, seeking social change by whatever means seemed expedient. But not long ago, he said, he had run across another revolutionary and it had changed his life completely. He can change yours, too, the man promised. Then he said, “My name is Eldridge Cleaver. I’m Living Proof.”

Bill Hill had told me one of the commercials would be a testimonial, and I would not have been surprised to have seen Charles Colson or Johnny Cash telling about what God had wrought in their lives. I try to keep up with the box scores on notable conversions, but I had somehow missed the news that the icy soul of Eldridge Cleaver had been warmed with fire from above. I was impressed that Texas Baptists would consider pumping hundreds of thousands of dollars into publicizing the testimony of a man who might still be regarded with skepticism and caution by some of his new white brothers. And I was especially curious about how the members of this largely working-class church might react.

I studied the lone black member of the group, a man about 45. Was he an Uncle Tom who would fear that the sight and sound of this panther in lamb’s clothing might stir resentment left over from the sixties and jeopardize his perhaps lately won and still tenuous place in a predominantly white congregation? Would he say of Cleaver, as Peter had said of Christ, “I never knew him”? No, he wouldn’t. “This is very beautiful,” he said. “It comes from a controversial person a lot of us can identify with. We know Eldridge Cleaver was searching for something he could not find in the world, but only in Jesus Christ. I had much the same problems in my life at one time. It was very hard for me to accept certain things, but now I am able to face these things and accept them.” That is not exactly revolution, but it isn’t “white folks always been nice to me” either.

A middle-aged woman who had taken much longer than anyone else to fill out her questionnaire spoke next. I sensed she was about to vent a little of the racist spleen we often associate with working-class fundamentalists.

“This was also my favorite,” she said. “It shows that Christ is a Man for all men. He is not a white man’s savior or a black man’s savior or a Jew’s savior. He is for everyone. I think every minority feels pressures and I think there are times in everybody’s life when they feel like they are a minority, even though nobody else may look upon them that way. When you are low man on the totem pole in your office and everybody says, ‘You do this’ and ‘You do that,’ and it seems like you do everything for everybody, then you can identify with the feeling of being a little bit left out.”

The final commercial depicted a child learning to ice skate with the loving help of a parent-figure in a unisex outfit like the Olympic speed skaters wear. The narrator told how important it is to have someone you can depend on when the going gets a bit hazardous and concluded with the slogan, “Learn to live with Jesus Christ.” I liked it best of the four. Its symbolism was aesthetically appealing and I liked the way it avoided both the negative connotations about human nature (though I am not especially sanguine about the natural goodness of our kind) and the spurious overgeneralization implicit in any case based on a single testimony. The nine focus groups agreed more strongly than on any other point that “Ice Rink” was clearly the poorest of the four commercials. “It was boring,” they said. “It just beat around the bush and didn’t really say anything.” “I can’t ice skate, so I don’t identify with that one at all.” “A waste of film.” I decided not to become a consultant on mass evangelism.

Ms. Briggs asked who they thought might sponsor commercials like these. Oh, the Catholics or SMU or maybe the Dallas Council of Churches. Not one named the Baptists. Baptists have W. A. Criswell; they don’t need Eldridge Cleaver.

The meetings with the Baptist groups were designed to see if any of the commercials were likely to run into the kind of opposition that might make funding or other forms of cooperation difficult. But the real test, everyone agreed, would be with those who described themselves as nominal or inactive Christians and those who openly acknowledged they were not religious in any conventional sense. A pool of such people had been obtained by distributing questionnaires in Dallas office buildings; groups representing both sexes and a broad range of ages had been selected from this pool. In keeping with the piety of the groups, we met at a neutral site, the Marriott Inn. Curtiss Grove, a partner in Louis, Bowles and Grove, was moderator for the evening. As we waited for people to assemble, he lamented having to pass up a cocktail party down the hall.

The group looked pretty representative of backsliders I have known: a workingman in his thirties; an overweight balding man who talked knowledgeably about the video equipment; a tall, thin older man who wore a tie with a leisure suit and looked as though he smoked a lot and was perhaps familiar with the taste of liquor; a woman who was pretty in the way that Southwest Airlines stewardesses are pretty, and a thin, serious man who appeared to be with her; a young woman about twenty who wore blue eye shadow and orthodontic braces; a neat woman in her thirties who looked like she was probably in charge of several people where she worked and had a reputation for getting things done on time; one of those ubiquitous, interchangeable young men with a moustache and styled hair and a preference for shiny shirts with sailboats or jockeys on them; a foxy brunette in a suede jacket and lots of bracelets and rings and dark fingernail polish who seemed a poor conversion prospect; and several others I knew then I wouldn’t be able to remember. For the most part, they represented a bit higher socioeconomic status than the Baptists I had visited the night before.

Grove is good at his job and easily elicited comments from the group. Interestingly, their reactions were not remarkably different from those of the active Baptists, except that none of them rated the Cleaver commercial highest and four of the twelve designated it their least favorite. (As it turned out, this response was something of an anomaly; the other two groups meeting at the same time felt strongly that the Cleaver spot was the best.) When asked what the commercial sought to accomplish, one man guessed it was trying to stir up pity for Cleaver. Another thought it too controversial even for minority-group people and felt its appeal would be limited to revolutionaries or people “with awful problems.”

Each of the other spots got three or four votes as the best of the lot, but what one felt was pungent, another would judge pedantic. The 28-year-old in the shiny shirt said he didn’t think any was much better than the others, since they were all about God and the church. A young man about nineteen seemed rather bemused by the whole business, as though he thought his sainted mother had somehow arranged to get him invited to a subtle soulwinning campaign, maybe even paid his way. But all things considered, I think this group uttered more pious clichés than the dedicated Baptists. Since they did not know they had been chosen because of their shared lukewarmness, they seemed to feel some need to let their colleagues know they were believers. In spite of what may have been a bit of overcompensation, however, I sensed almost none of the assurance I had seen and heard the night before. Several people got sad looks on their faces and lit up cigarettes. I believe they were pretty serious about it all. I had agreed not to ask any questions and I may have misread their reaction, but I had not expected what I sensed and it seemed unmistakable. I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that the older man in the leisure suit had started going back to church with his wife.

As before, almost no one perceived the commercials as Baptist in origin. The President’s Council on Physical Fitness, the Cerebral Palsy Association, an ice rink, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Channel 39, and Sominex all seemed as likely as the Southern Baptists to sponsor such spots.

On the third night, self-designated unbelievers viewed the spots. This was the crucial test, the people at whom the main thrust of the campaign was aimed, but their preferences turned out to differ little from their more pious predecessors. Neither “Morning News” nor “Promises” struck a responsive chord. One man who at first thought “Morning News” was touting CBS news was irritated when it proved to have a religious theme. Another picked up the religious slant earlier but just thought, “Here we go again.” A woman complained that “it doesn’t tell me what to do with my problems, except give them to someone else. A little information about how Jesus is going to handle my problems would be helpful.”

“Promises” caused even stronger negative reactions—one woman characterized it as “hateful” and said, “It made me want to lock myself in a room and shoot anybody that makes promises”—and “Ice Rink” once again came in as the unanimous last choice. One woman described it as “childish the way they wanted you to put yourself in Jesus’ hands with no mention of adult choices.” Another took issue with the whole ice-skating metaphor; she didn’t feel at all like an ice skater, but rather “a yo-yo, every day I feel like a yo-yo.” A man about thirty said he felt a better metaphor would be someone playing poker, or perhaps even solitaire. I doubt seriously the Southern Baptists will pick up on that.

Once again the Cleaver commercial was picked as the best—unanimously by one caucus. A man who freely called himself an agnostic said, “I know what Cleaver’s life has been, and if this guy says he can pull it out with Christ, well, I may think there is something to it.” He admitted to some doubts whether Cleaver might just be trying to escape a prison sentence by publicly embracing religion, but rejected them: “I have not agreed with Cleaver in the past, but I have respected his integrity.” Others did question Cleaver’s sincerity, but what carried the day was the feeling that “it gave me a choice. It told me what his opinion was, but it didn’t say, ‘You take my opinion, buddy, because it is good for you too.’ ”

The success of the Cleaver spot naturally raised the question of whose testimonials people could accept. The subject shouldn’t be an ordinary person, someone from the viewer’s own neighborhood (“I would figure someone was just trying to get on television and get some publicity”); it certainly shouldn’t be Richard Nixon or Patty Hearst (“It is still too close. With Cleaver you can almost feel the guy has paid his debt and now has a whole new slant on life”). The ideal person, one man thought, would be a noncriminal figure who still had room for notable repentance—the two names mentioned were Billy Graham and Earl Scheib, the $29.95 auto paint job man.

Interestingly, the non-Christians had no difficulty accepting the idea that Southern Baptists might be behind the commercials. The use of testimonials seemed “more Baptist” than any of the other approaches, even though Eldridge Cleaver seemed like an unlikely star. One woman suggested that if Baptists were indeed the sponsors, they would do well to hide the fact, since “many people are turned off by their extremist actions.”

If the consultants were looking for useful criticism, the non-Christians gave them plenty of that, but if they were looking for some signs that Good News Texas was going to send unbelievers flocking to church, the meeting provided little basis for hope. One man quickly deduced that his group contained no practicing Christians and said, “I think people like us tend to rely on ourselves rather than look outside for some kind of placebo. I don’t care whether people believe in Jesus or Muhammad or Darrell Royal; just because they believe it and get out and preach it doesn’t mean it’s true. I just don’t buy the idea that you can blindly put your faith and trust in any person, including Jesus.”

The bad news for Good News Texas was that the non-Christians didn’t like the whole idea of religious commercials. “I am turned off by commercials of this sort,” said one. “It cheapens religion to sell it like toothpaste.” “There is nothing in these commercials that appeals to me in any way or makes me feel I should investigate Christianity,” another said. They make it sound like Jesus is going to open up a used-car lot.” But one man who also had a negative reaction to selling Jesus on TV conceded that “television is such a powerful communications medium that if they use it right, it can help. There are some people whose only way of touching anything outside their home is television.”

It is Bloom’s job, then, to see that TV is used right. The hope that any single commercial might provide Baptists with an offer lost Texans could not refuse seemed pretty well dashed. Still, the response to news that the sins of the apostle of Black Power had been washed white as snow had proven sufficiently promising to convince Bloom and the BGCT that testimonials were the route to take. At the state convention in San Antonio two weeks later, L. L. Morriss proclaimed that the theme of Good News Texas would be “Living Proof” and would concentrate on “presenting the testimony of people who have experienced the saving grace of our Lord.” Dr. Landes announced that Baylor football coach Grant Teaff and actress Jeannette Clift George had agreed to serve as honorary co-chairmen and played a tape from Billy Graham, who said the world was hungry for good news and he was pleased to have a part in the boldest evangelistic venture in the history of Texas Baptists.

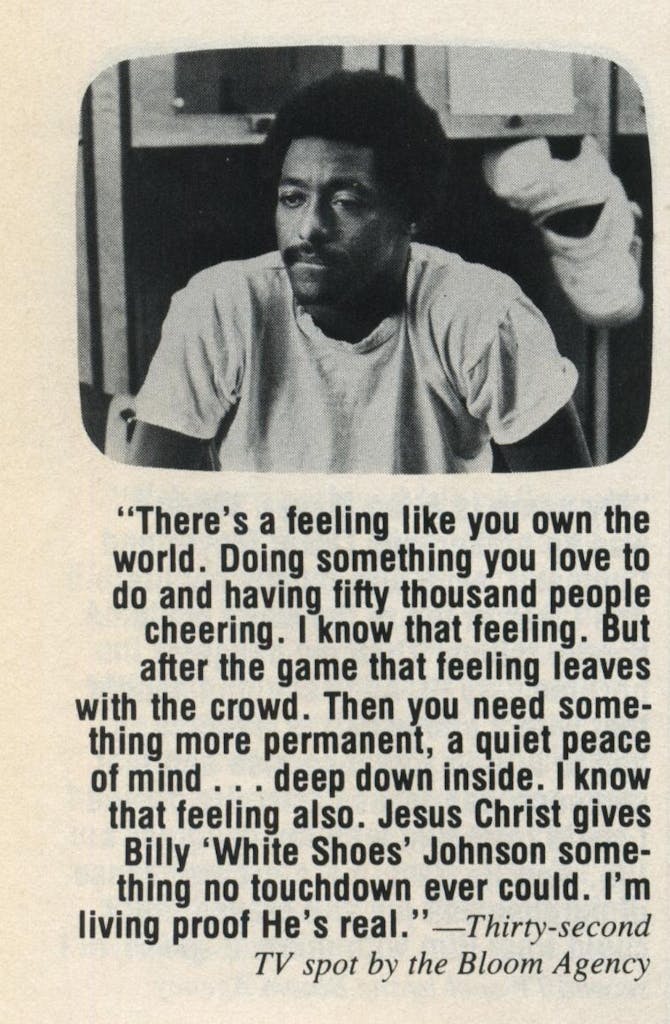

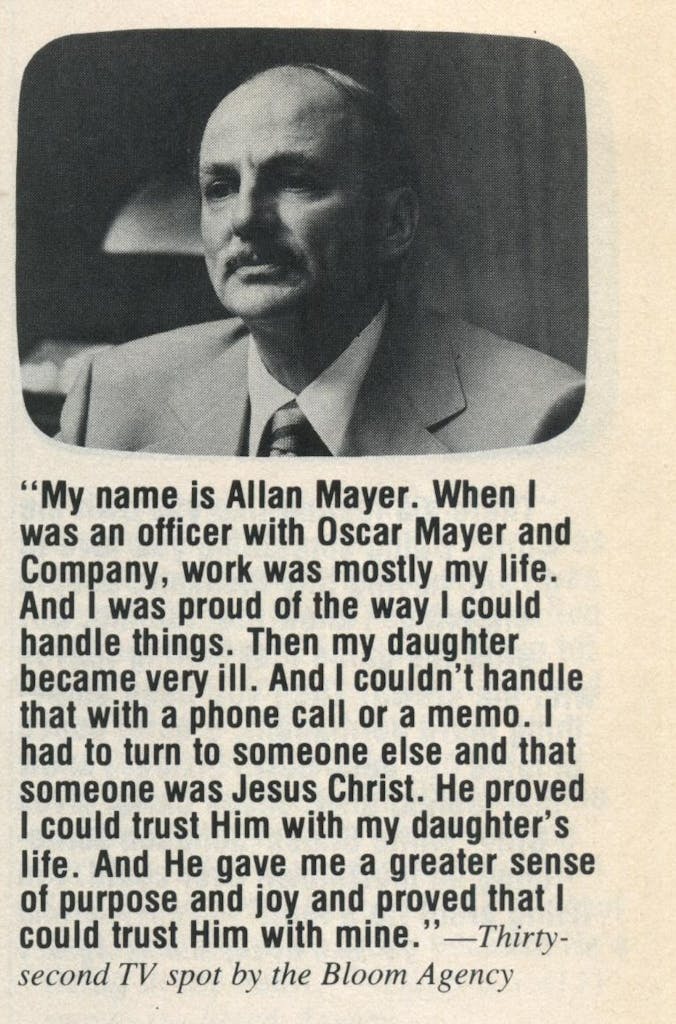

By the first of December, some of the top converts in the country had been lined up to add their testimony to Cleaver’s. There had been minor problems. Some Christian entertainers had been discouraged from participating by their agents, who feared it might hurt their image with the public. Others had been screened out when their faith was adjudged not yet solid enough to guarantee against an embarrassing relapse during the campaign; no one, for example, would want to take a chance on Jerry Lee Lewis if he were suddenly to go into one of his periodic conversion phases. The final list included country singers Jeannie C. Riley and Connie Smith, Mexican musician Paulino Bernal, Consul-General of Honduras Rosargentina Pinel-Cordova, Houston Oiler Billy “White Shoes” Johnson, and Allan Mayer of Oscar Mayer and Company. A couple of big ones had gotten away. For some reason, Charles Colson had backed out and had to be replaced by Dean Jones, and a former Hell’s Angel who conducts a bike ministry on the West Coast didn’t leave a forwarding address when he set out on his latest missionary journey. But all the others were ready to go and film crews were heading for Nashville and L.A. to record their stories. We’ll see the results soon.

As I wait, I am aware of poignant feelings. I have watched and listened as good, sincere, intelligent men and women groped for a way of making that which stands at the center of their lives plausible and attractive to those who live outside the sacred canopy. Perhaps it will work. I think I could accept that in good grace. I generally feel pretty comfortable around people who take their religion seriously, especially if it is one of the leading brands. But I confess I do not believe historians will remember 1977 as the year the Great Awakening came to Texas. I expect Baptist churches may be stirred up considerably and some wayward Christians may return home like the prodigal. These are the groups that have always responded best to the call of revival. The main work of evangelism in American history—with, it should be noted, some exceptions—has been to keep believers plugged into their systems. That in itself is a significant accomplishment and may well justify the cost and effort involved. Of course, here and there a real scoundrel or a true skeptic may be turned around and set on the Glory Road, but I expect Good News Texas will come and go without making a great deal of difference in the lives of the 4,700,000 sinners at whom it is primarily aimed. That will no doubt discourage a lot of folks, but maybe it shouldn’t. After all, even though He knew how to use a bit of dash and sparkle to draw a crowd, Jesus never got anything like a majority, and if the Word of God is anything to go by, He never expected to (Matthew 7:13-14).