This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The kiss begins, not with the lips, but with the eyes. When the first faint murmurings of a passionate heart stir lovers to action, it is the invitation of an eye—if all is right with the world, a deep, soft, luminous pair of them—that brings the nascent kiss into being. Let the troubadours prattle of moist lips, the Tuscan poets of heaving bosoms, the Romantics of ivory complexions, and still I will insist on the preeminence of the eyes. Those burning orbs are more seductive than all the perfumes of Arabia.

You will notice at once that I brook no arguments when it comes to kissing. Look elsewhere if you seek an objective reporter, a dispassionate critic who can avoid the descent into purple prose when he describes this enduring custom. I appear as an advocate. Were it not for the sorry state of kissing in America today, none of this would be necessary. But I’m afraid the seventies may well be remembered as the decade in which the kiss—at least what I have always thought of as the kiss—became all but passé.

Let me make it clear that I’m not speaking in any simpleminded statistical sense. I am well aware that more people, in more places, are kissing one another in more ways than ever before. This is precisely the problem. Like the national currency, the kiss begins to lose all value at the very moment it becomes available to all, even those who have done nothing to earn it. (When was the last time you saw a kissing booth? No wonder. They aren’t worth a nickel anymore.) I hadn’t realized how far we have fallen until I attended a wine and cheese party last year in Los Angeles at which I was kissed in quick succession by two women, both of whom I had met only that day, neither of whom knew what she was doing. (These kisses were the smack-on-the-cheek variety, which are actually rubs on the cheek and smacks of air.) This is hardly the first odious social custom exported by California to the rest of us, but it is one of the most unsettling. Lest I be misunderstood, I am defending kissing only in its highest sense, kissing as it was meant to be practiced, and not kissing between sorority sisters, kissing at wine and cheese parties, or kissing among more than two people at once. In short, I extol one kiss and one kiss only—the kiss of romance.

The romantic kiss, as I have said, begins with the eyes—what is not clearly seen cannot be properly kissed—but it is much more than that. Except for sex, kissing is the only human act that fully engages all five senses. Beyond the smoldering eyes, beyond the commingling of mutual desires, the romantic soul soon cries out for contact, and to the wonder of Sight we add a second sense, intrepid Touch. The embrace! At this point the commitment is made. The kiss, for better or worse, must happen. A whiff of fragrant hair sends Smell dancing into action, and as the kiss rushes to its fruition, a thousand little cupids dart through the bloodstream. Her lips part, but only slightly; his descend as the twin sisters Sound and Taste envelop these heedless heads—a sound faint and surreal, a susurration, but such a taste! What follows is an indescribable blur that I am helpless to describe, for it includes the accumulated wisdom of 10,000 years of human history.

Kissing is an old marvel—an old, old marvel whose origins are hidden somewhere within that turbid region of the unconscious reserved for matters of lust and passion. To our everlasting discredit, the first kiss was not recorded. But the anthropologists envision a hirsute primitive, some ten millennia ago, endowed with the beastly habit of eating any and every object that seemed desirable. It mattered not whether the object was a lamb chop, a woolly mammoth, or a woman—let it be tasted nevertheless. We speak more truly than we think in saying that the way to a man’s heart is through his stomach. In ancient Egypt the same word was used for “kiss” and “eat,” leading anthropologist Robert Briffault to remark, “The desire expressed by lovers to ‘eat’ the object of their affection probably contains more sinister biological reminiscences than they are aware.” So thought the Chinese, who, sadly, were the last great culture of the world to learn this art; as late as 1900 they regarded the custom of mouth-to-mouth kissing with horror, as an act verging on cannibalism. And perhaps they were partly right. The kiss, after all, is an attempt to appropriate part of another’s body to your own use and pleasure.

But I’d rather not dwell on this. My sole purpose here is to trace the rise, practice, and precipitous fall of romantic kissing, and for this I enlisted the aid of Dr. Vaughn M. Bryant, Jr., an anthropologist at Texas A&M University. Dr. Bryant is a passionate scholar as well as a scholar of passion and, as far as I know, the only accredited expert on the history of kissing.1 This eminent man claims to have discovered the first recorded instance of human kissing, which occurred around 2000 BC in the area of present-day India. The language arts being what they were at the time, it is well-nigh impossible to tell whether this kiss—which involved probing with noses, à la the Eskimos, more than with lips—represented romance or was merely a form of greeting. But no matter. Five hundred years later, the record was clear: from the Kama Sutra we learn no less than two hundred forms of kissing, all of them lascivious, some downright kinky. From India the kiss spread to Persia and Greece, and thence by conquest to the Romans, the Germanic tribes, and the Scandinavians. The fabled European lover was born.

This may be the place to clear up a matter that has troubled the minds of the learned for some time now—namely, is kissing an instinctive desire common to all, or is it learned by imitation of others? Darwin was the first to consider the possibility of kissless cultures. However grim that theory may sound, he had evidence: he cited the Maoris, Tahitians, Papuans, Australian aborigines, Somalis, Laplanders, and Eskimos as examples of people to whom kissing was foreign in the nineteenth century. What Professor Darwin failed to point out, though, was that these tribes licked one another’s cheeks, bit lips, sniffed hair, exchanged breaths, and practiced a dozen other variations of the same thing. In other words, they were trying to get the hang of it even then. The proof is that when American sailors—who at one time represented the best kissing country in the world—were stationed on kissless Pacific islands during World War II, the natives were wholly converted in a matter of months. (I am speaking of the women; the men took longer.) Even the Eskimos are coming around; only the elderly continue to eschew mouth-to-mouth embraces, and soon nose-rubbing will go the way of votive offerings. All of this shows that the kiss is international, timeless, and altogether natural.

The only hindrance to universal kissing in the American style was the specter of that dry-lipped zealot: the anti-kissing magistrate. This, of course, is a recurring theme in osculatory history: the effort by forces of darkness—usually judges, priests, or elderly ladies—to repress the kiss by force of law, religious custom, or social pressure. Even the Romans wrote into their judicial code a statute giving full rights of marriage to any virgin who could prove she had been kissed. Likewise, the aptly named Pope Innocent III banned all kissing during religious services after the liturgical “kiss of peace” started to get out of hand.2 In times like those, when romantic kissing could lead, on the one hand, to prison, and on the other, to hell, it’s little wonder that civilization passed into the Dark Ages.

And that, by and large, is where kissing stayed right up until modern times—in the dark. Without going into all the details, suffice it to say that kissing—in a remarkable display of hypocrisy that lasted more than a thousand years—was as ardently celebrated in private as it was condemned in public. There were occasional lapses—as in the hedonistic revels of seventeenth-century France—but the poets are quite clear on this point. Kiss to your heart’s content, they wrote, but never kiss and tell.

Not even the Americans, whom I consider the true pioneers of the romantic kiss, were immune from the kissing inquisitors. In 1660, for example, a woman named Sarah Tuttle was actually fined by a judge in New Haven, Connecticut, for smooching indiscreetly. The story goes that the bold Sarah ventured into a neighbor’s home to borrow thread, but finding the house full of merry, congenial, and rather lewd company, she decided to stay. The man of the house, one Jacob Murline, turned out to be no gentleman. He snatched Sarah’s gloves and refused to return them unless he received a kiss. “Whereupon,” reads the court record, “they sat down together, his arm being about her and her arm upon his shoulder or about his neck; and he kissed her, and she kissed him, or they kissed one another, continuing in this posture for about half an hour.” The judge pronounced Sarah a hussy and imposed a fine, dismissing the rascal Murline with a warning.

The resilient kiss outlasted Puritanism, however, and eventually the press of lip on lip was rightly accepted as the irresistible urge of every feeling person. Public kissing, on the other hand, was not. The Edwardians, for example, had to snatch their kisses wherever they could. They kissed when trains went into tunnels, they kissed in carriages, they kissed furtively on bus tops, they kissed in the cabins of Ferris wheels, and, of course, they made the most of the London fog.3 Curiously, it is this type of culture—in which everyone is doing it but no one knows who is doing it with whom—that seems to spawn the richest kissing literature. The British poets of the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries are largely responsible for the fund of images we now use to describe kissing, and their most popular metaphor by far was honey—as in “honeyed lips”—perhaps because honey tastes and smells sweet. This seems to me an altogether inappropriate and terribly archaic term to describe the kiss as we know it. American kissing is fireworks, bursting rockets, a shaking of the earth at its core—but honey? Were it not for the decadence of our national literature, this metaphorical deficiency would have been remedied long ago.

Americans have a special stake in preserving the integrity of the kiss, for it was the United States that brought kissing out of the Dark Ages once and for all. All of these historical musings—our journey from the prehistoric cave through the Orient and the Roman court—have been but a prelude, for now we come to the true origins of the romantic kiss. Let the Indians claim what they may, the first romantic kiss occurred in 1896, and it lasted exactly thirty seconds. That was the length of a movie called The Kiss, starring May Irwin and John C. Rice, that immediately drew startled outcries from the local defenders of the public morality in New York. It was not the first theatrical kiss, of course, but it was the first one in which the audience could see clearly what was going on. “Magnified to gargantuan proportions,” groused one critic, “it is absolutely disgusting. Such things call for police interference.” He and others like him were shocked not so much by what they saw—it was a rather lame kiss—as by the possibility of what they might see next time. The close-up camera revealed all the subtleties of the lip and the eye that until then had been invisible even to the people doing the kissing. Those with active imaginations left the theater with intoxicating new ideas about what a kiss could do.

So impressive was this new visual textbook—a sort of McGuffey’s Reader for semiliterate lips—that instead of art imitating life, life began to imitate art. At first the result was an epidemic of atrociously convoluted (and sometimes painful) kissing styles. Silent movies may have set the science of kissing back thirty years as young dandies trained their lips in emulation of stars like Ronald Colman, William Haines, Antonio Moreno, and, most influential of all, Rudolph Valentino, the first international sex symbol in an era when sex scenes ended with the kiss.4 There were two reasons for this artless bussing. One was the baroque technique of the cinematic kissers themselves (after all, Hollywood producers were just beginning to learn, too). Valentino, for instance, would start at the hand, travel up the arm, kissing all the while, then move round the back of his lover’s neck and thence, eventually, to the lips. This kissing odyssey would continue as he bent the woman back until her torso was arching toward the floor, her back cradled against his forearm. Conveniently, Rudolph Valentino always fell in love with contortionists.

The second problem was that the censors, who always seem to be lurking wherever kissing gets a foothold, were back in force. Will Hays, the movie-industry policeman adored by the Church and scarcely tolerated by the Hollywood producers, swore his allegiance to God, family, and conventional courtship, a policy that boded ill times indeed for the incipient romantic kiss. Hays’s infamous Production Code, a grocery list of cinematic forbidden fruit, was quite clear on the matter: “Excessive and lustful kissing, lustful embraces, suggestive postures and gestures, are not to be shown.” In practice, this meant that kisses were strictly rationed, so directors were forced to get all the passion they could show into the fewest possible frames. The result was the notorious “clinch,” in which otherwise stylish lovers suddenly grabbed each other like frightened octopi, pressed their constricted lips pell-mell onto any available part of the face, and mashed their noses flat on the theory that what can’t be shown explicitly can be implied by sheer physical force. Then the scene would cut away to a raging thunderstorm, a fireworks display, or a horse whinnying and kicking at his stall to indicate by indirection what the kiss might have been like had we been allowed to see it.

More helpful than the male stars were the early actresses—Nazimova, Pola Negri, Vilma Banky, Greta Garbo—who taught both sexes the multiple meanings of the potent feminine eye. Again, necessity was the mother of labored invention—first, because the movies were silent; second, because any attempt at outright seduction would be scissored by the Hays office anyway. Hence these women developed looks for every situation—eyes that said “I want to be kissed,” as well as “I don’t mind if I’m kissed,” to “I won’t be kissed,” to “Stop it, I like it,” to “I like it, but stop it,” to “I don’t like it and the next time you do it I’ll still be cold as a mackerel.” This ocular talent, which seems to be natural to women only, is one of the few valuable lessons relevant to kissing to survive the silent era.

In retrospect, it seems that the heyday of romantic kissing occurred during the late thirties and early forties.5 During that decade kissing was discreditable enough to be fun but common enough to be entirely safe. It was also the period when the American public wised up, recognized most of the movie kissers as talentless dissemblers, and developed a national (and natural) style. In this era many moved beyond the lips proper and showed a healthy respect for the neck and shoulders as well. And for the first time we had a civilized set of rules for playing the game.

These rules are now more often breached than observed, so it may be instructive to review them here. The kiss? First of all, the kiss is not necessarily a form of foreplay. I hate even to mention this subject, and in so doing I fly in the face of several scientific luminaries, including Sigmund Freud, Havelock Ellis, and Alfred Kinsey, all of whom have suggested (each in his own way) that kissing is merely the prelude to loving, a proleptic hors d’oeuvre, a mere trifle. This is not to say that these mechanistic lovers failed to appreciate the kiss in a purely erotic sense, but merely that it would always play second banana to what followed. Here is Freud, for example, on kissing: “The kiss between the mucous membranes of the lips of two people is held in high esteem among many nations, in spite of the fact [emphasis added] that the parts of the body involved do not form part of the sexual apparatus but constitute the entrance to the digestive tract.” The good doctor, in other words, would rather get down to business.

I would rather not, at least not at first. The kiss, I insist, is itself a terminus and a reward. Kissing is a culmination of desires at once spiritual and physical, and how Castiglione could speak of a “platonic kiss”—unless he meant it as the buss required of sisters and brothers—is beyond comprehension, for there is nothing at all platonic about a properly passionate osculation. What did the knight pine for, if not his lady’s ruby reds? And there he found a sensual pleasure quite different from the indulgence of a brothel, yet still entirely satisfying in its own way. He who kisses with immediate expectation of something more than a kiss will be too preoccupied ever to become a genuine romantic kisser.

The second thing to remember is that there are no indifferent kisses. A kiss by its very nature is either good or bad; there is no way to feel neutral about it, especially on the first try. If you have any doubt at all, it was a bad kiss, and you shouldn’t repeat the experiment. Some people are not made for each other. Kissing provides the proof.

The third immutable doctrine of romantic kissing is that a woman is never responsible for the success or failure of a kiss. At the risk of offending my feminist friends, I will put it bluntly: her role is to submit. Someone has to be in charge of making the kiss happen, and all the preparatory moves are logically left to the man, equipped with the advantages of height (in most cases) and strength (for maintaining balance). I don’t mean to imply that a woman is not free to refuse a kiss. On the contrary, a refusal merely illustrates how miserably the man has failed. Nine tenths of a successful kiss occurs before the kiss takes place, so a recalcitrant lover is the final indictment of an inept would-be kisser. Some men may find it difficult to distinguish shyness from active dislike. If this is the case—and a man bumbles into an unsolicited kiss by mistakenly assuming his target to be coy—he should be rewarded with a resounding slap on the cheek. There is no excuse for his not being able to tell by her eyes. If the woman is genuinely shy, he should persist until she tightens her lips like a vise, straightens her back, and begins shaking her head from side to side. At this point he should withdraw his lips but resume the effort later.

Perhaps you think by now that I am hopelessly doctrinaire in my opinions, that I have left nothing to chance and the inspiration of the moment. Nothing could be further from the truth. There are two mystical questions that will always be debated by serious lovers, and I present them here for your own verdict. First, does lip size matter? Second, should the eyes be open or closed? Actually, I think the first question has a misplaced emphasis. It’s not how big the lips are, but how big all four lips are in relation to one another. The only lips I personally have trouble with are the razor-thin sort that stretch across the entire breadth of the face. There is virtually no way to get at all of them at once. One of my colleagues maintains that Brigitte Bardot has the most kissable feminine lips known to man; of course, hers are oversized, pouty, and so wide that you could get lost in them. But I think an equally strong case can be made for thinner lips on the scale of, say, Hedy Lamarr’s. If the women I talked to are representative of their gender, their preferences for the lips of Paul Newman, James Dean, and Montgomery Clift would indicate that females are attracted to men with ample lips.

The custom of closing the eyes during the kiss is not recommended for a man, mainly because it deprives him of the pleasure of looking at her eyes. It is recommended for women. There is no good reason for this double standard.6

Finally, there has never been a romantic kiss worthy of the name that did not include some element of surprise. This does not mean that we should, for the sake of variety, return to the days of clinching, bear-hugging, and loathsome smacks. Instead I propose this rule of thumb for men: never kiss a woman at her doorstep. That’s where she most expects it and will least enjoy it. Try it in kitchens, on elevators, in parking lots, on park benches (although public kissing should be used sparingly for maximum effect), and on the floors of swimming pools. The moment must be exactly right—I can’t help you much here—and it must always silently tell her, ‘‘I can’t wait until later.” If she says something discouraging like “What do you think you’re doing?” you can’t blame it on the place, for any place has potential. You chose the wrong moment—or possibly the wrong woman.

Yet another variation of the surprise kiss is the custom once known as “stealing a kiss” but now practiced by hardly any but the most reactionary defenders of tradition. That’s a pity, for stealing kisses involves mystery, adventure, trepidation, a little flattery, a little mischief, and an effect that lasts far longer than any other kiss. The key ingredient here is the object of your kiss. It must be a woman that you know well enough to hug but not quite well enough to kiss. Timing is everything. First, you must be alone with her, if only for a few seconds. Second, it should be a moment when you would naturally touch her anyway, as when you hug a friend after a long absence. Third, it should be done swiftly and lightly, but directly on the mouth, as though to say, “Oh, my goodness, we were about to shake hands and there I went and kissed you.” Then you should draw away and immediately begin talking about any unrelated topic. Needless to say, the desired effect is mystery. Whatever else happens, she must never know whether you were serious or not. Henceforth, whenever you meet her, she will suddenly wonder whether you are about to kiss her again, but of course you won’t. Kisses can be stolen only once.

The practice of indiscriminate kissing now going on at the fashionable cocktail parties of Dallas and Houston is definitely not part of the stolen-kiss tradition. Those kisses—the polite pecks on the cheek served up to whoever walks through the door, coming and going—are nothing more than the frail remnants of a culture that is rapidly kissing itself out. They signify nothing, and are twice as awkward as a handshake.

The man responsible for this abhorrent practice is Leonard Bernstein, the conductor, who first popularized social kissing in 1962. (Until then, it had been confined largely to members of the acting profession.) In that year, at the opening of Lincoln Center in New York, Bernstein used the advantage of a brief intermission to plant a kiss directly on the cheek of Jacqueline Kennedy, an indiscretion that Time magazine trumpeted to the world as the latest practice among the Camelot aristocrats. One thing led to another. After all, if you can kiss the President’s wife, whom can’t you kiss? And after a while everyone and his brother was kissing everyone and her sister on the slightest of pretexts. Even the caliber of presidential kissing has plummeted over the past eighteen years. Jimmy Carter in a reception line is a frenzied kissing bandit who lays ’em thick and heavy on any woman who comes along.

Now I believe Leonard Bernstein to be an honorable and discreet man, and my guess is that he intended nothing more than to steal a kiss. But in doing so he touched off a popular solution to a very real social problem: what are you supposed to do when a man and woman are introduced for the first time? Some women step boldly forward, offering their hand and pumping it briskly. Others offer a droopy, limp-wristed hand that appears so fragile as to break off the arm if it were actually shaken. Some women merely nod. Some do nothing at all. And some seem not to be able to make up their minds, inclining their heads forward, then drawing back, lifting their hands three inches, then letting them drop. All of this can be very taxing to the man who is trying to put these fidgety females at ease.

Yet the Jimmy Carter solution—kiss them all, whether they like it or not—seems to me to lack subtlety and, well, class. I have a better proposal: bring back hand-kissing. I don’t make this suggestion lightly. As a model I suggest we look to the Mexicans, who have preserved among the upper classes a number of the romantic subtleties that have long since been abandoned in America. I first discovered the unfailing appeal of hand-kissing a year ago in Mexico City. The circumstances were a little embarrassing. I had stepped off the press bus and wandered into the wrong entrance of the City Theatre, and there I found myself in the middle of President José López Portillo’s official receiving line. (He was sponsoring a command performance of the Mexico City Philharmonic on the occasion of President Carter’s state visit.) Not knowing what else to do, I continued on through the line, where I made two observations. President López Portillo, with impressive grace, was kissing the hands of the ladies, and President Carter was not kissing anyone at all. Standing beside such an effortless and stylish kisser, Carter’s instincts told him he’d best do nothing.

And of course the President’s instincts were right. The kissing of the hand is infinitely preferable to any other form of greeting. It flatters and yet it implies no romantic intentions. It has all the advantages of the cocktail kiss—spontaneity being the chief one—and none of its disagreeable connotations.

The comeback of hand-kissing will be difficult. I realize I have set no easy goal for the nation; it will most certainly meet with resistance. I doubt that the custom could ever penetrate such lost cities as Los Angeles and New York. But I have already tried it once, on a lady thirty years my senior, and can report spectacular effects. (Kissing elderly ladies, by the way, is one of the noblest ways to win their affection.) And there is one more reason for hope. The conductor that night in Mexico City was Leonard Bernstein, flown in for the occasion, and he was kissing hands, too. It’s never too late.

Once we bring back hand-kissing, the way will be cleared for a wholesale recovery of the national romantic honor. Kisses will proliferate, but only the kind of kiss that signifies the mysterious conjunction of a man and a woman who have lost their capacity for rational thought. Kissing will be spontaneous instead of calculated, sensual instead of social, laden with unspoken intentions instead of a substitute for “How are you?” Then, and only then, will America reclaim its rightful position as a land of romance. Only then will we be able to say, with Humphrey Bogart, that the fundamental things do apply.

1I am indebted to Dr. Bryant for several of the facts in this article. On one matter we differ. He insists that kissing depends on the use of only three senses—touch, taste, and smell—whereas I hold out for all five. On this point, and this point only, I suggest Dr. Bryant return to his laboratory.

2The Catholic Church made it official at the Council of Vienne in 1311–12. Henceforth, said the church fathers, kissing between unmarried people that was “done with the intent to fornicate” would be deemed a mortal sin, even if the kissers did not go ahead and fornicate. But kissing as “a carnal delight limited to kissing” was merely a venial sin.

3The English have always been the best kissers in Europe, contrary to the popular myth that the French wrote the book on osculation. The so-called French kiss is actually a German specialty—called the Zungenkuss—that was exported to the rest of the continent. The English made the most of it. By the fifteenth century, according to the Dutch scholar Erasmus, they were regular kissing fools.

4Students with a special interest in cinematic kisses, especially those of the postwar era, are referred to “I Found Romance at the Bijou Theater,” on page 86 of this issue.

5Historians generally date the closing of the kissing frontier around 1948. I believe that it occurred earlier, in the year 1940, during a kiss between Regis Toomey and Jane Wyman in the otherwise forgettable movie You’re in the Army Now. Toomey kissed Wyman for a full 185 seconds, nonstop, and eluded the long arm of the Hays censors once and for all. Shame on you, Regis, and thank you.

6For a dissenting opinion, see Hugh Morris, The Art of Kissing (Doubleday, 1936), a slim little volume published in kissing’s golden age that serves as an encyclopedic how-to guide for those who can’t teach themselves.

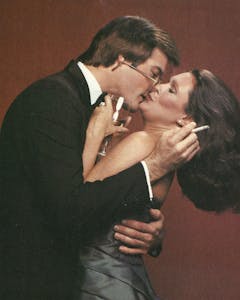

How Not to Kiss

How depressing! What a horrible kiss! His cigarette is going to set fire to her hair, her drink is going to spill all over them both. His aim was so bad that her nose knocked off his glasses, his lips are off to the side of her chin where they’re doing no good at all, and she’s all puckered up for nothing. And he’s pushed her over so far that her back’s probably in a spasm. But see at right how much these lovers improve with a little coaching.

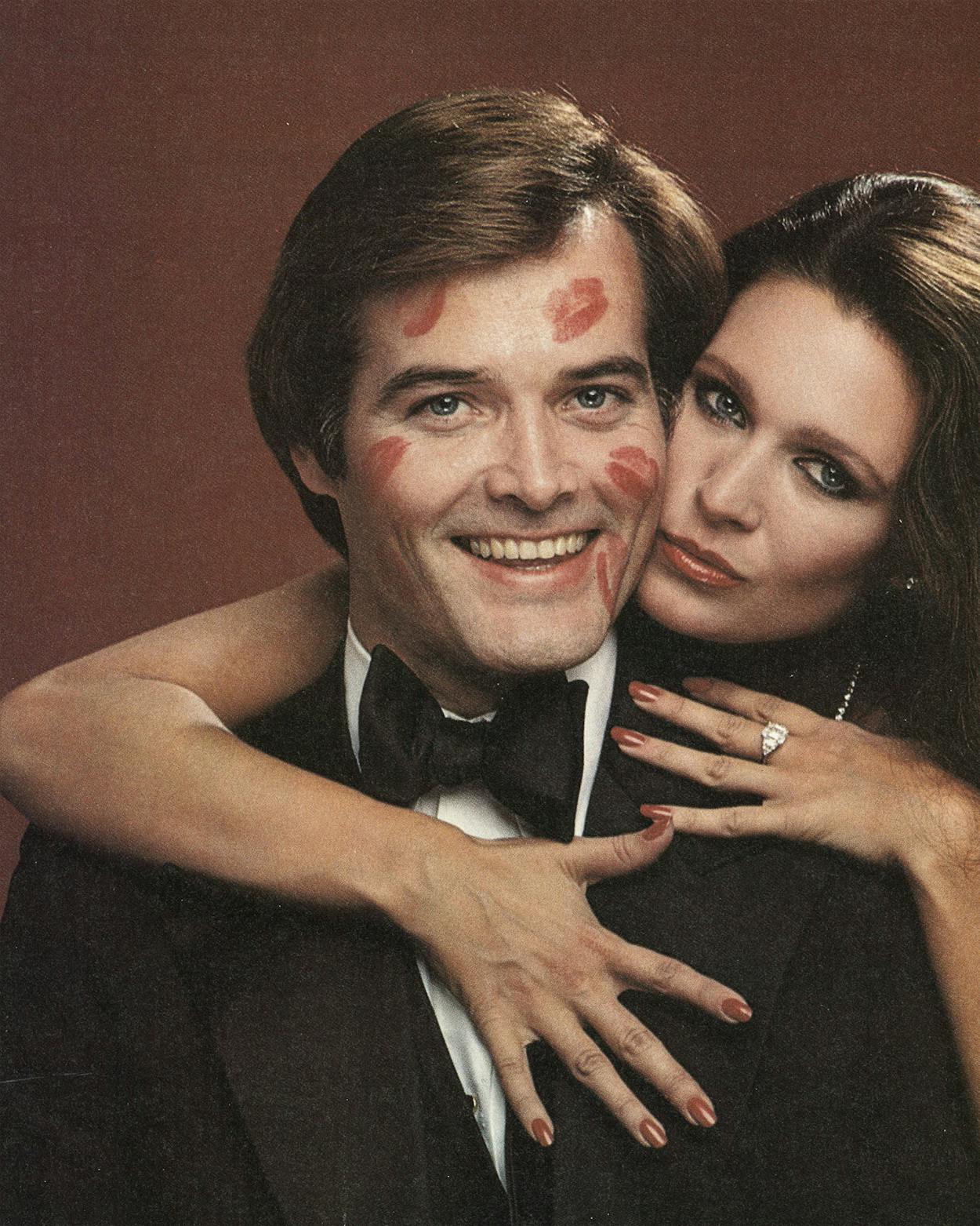

How to Kiss

First step: Establish eye contact. He should look deeply into the woman’s right eye. (Looking into both eyes at once is called staring. Very unromantic.) She should return the look, with perhaps a slight smile. She should not bat her eyelashes. Contrary to popular belief, that doesn’t make a woman more appealing. It makes her dizzy.

Second step: Make the initial touch. He touches her cheek gently as she lifts her chin. The touch tells her he is moving in the right direction and distracts her attention from his left arm, which is beginning its sweep around her back. (Personal to you men: Keep those hands warm. Startle her now and you’re back to discussing the weather.)

Third step: Embrace. She parts her lips slightly while moving her arms around his chest or shoulders, depending on the lovers’ relative heights. Now comes the most important moment. The man . . . pauses. With this their hearts instinctively shift into higher gear. This split-second hiatus separates romantic fervor from gross carnality.

Fourth step: Make the earth move. At this point there is only one more rule: don’t miss the target. Once the kiss is in progress, the art of osculation dissolves into thousands of amorous options. We have passed here from the social realm into the mystical. If you are a third party in a room where step four is reached, your duty is to leave, just as we will now.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads